The Japanese Pantheon Of Gods Explained

No matter where you look, there's a pretty good chance you'll see a smattering of ancient mythologies seeping their way into popular culture or even just general knowledge. Greek and Roman mythology are the two really big ones that have a tendency to crop up, especially in western culture. After all, who hasn't heard of the stories of Cupid or Hercules of the Trojan War? For that matter, you'd just need to take a look at the names of the planets in the solar system to see just how deeply entrenched Greco-Roman mythology is in everyone's daily life.

But if you turn your attention away from the more popular mythologies, you'd find that tons of places all around the world have their own ancient mythologies, too. Japan is just one of those places, and Shinto – Japan's native religious system (via Britannica) – provides a rather long roster of gods and spirits that make up a very full pantheon.

Really, "very full" might be a bit of an understatement. Putting together an exhaustive list of every single recognized god in the Japanese pantheon would be an endeavor of truly epic proportions – the kind that would probably require a trip to every single town in the nation (via World History Encyclopedia). So while you won't be seeing anything near a full list of the pantheon in this case, here's a rundown of how the mythology works, as well as a few of the prominent gods you can expect to hear about.

What are kami?

Just to be completely clear about things, the gods of the Japanese pantheon actually go by a slightly different term – more specifically, they're called "kami," and the way they work isn't quite the same as what you get with the gods of other pantheons.

Per BBC, the best English translation of "kami" is more like "spirit," though it's a pretty all-encompassing term. Put at its simplest, kami are often seen as the manifestation of different forces of nature or elements, though the list of kami also includes beings who more closely resemble the divine gods of other mythologies. That said, they're far from omnipotent; really, they're not all that different from everyday mortals, living on earth alongside humans and even taking up residence in the simplest of items, such as mirrors (via Britannica).

And that's kind of where the concept of kami becomes a little more complicated than the usual spread of gods you probably hear about in western media. Because kami aren't necessarily always distinct beings, but rather the divine or mystical element in just about anything. What's that mean? Well, it basically means that there can be an element of kami in something that's seemingly mundane. That nature can present as the simple beauty of towering mountains or peaceful lakes, but also the soul of living things (humans included).

Amenominakanushi

If there's a pantheon and mythology to talk about, then it makes sense that there would be some kind of an origin story for the entire world, right? So, in that case, just who was the deity that started it all?

That would be the deity named Amenominakanushi. Referred to as the "All-Father of the Originating Hub" by professor Noah Levin (via Libretexts), Amenominakanushi was the first kami to come into existence, forming from primordial chaos, and is further known as one of the "three kami of creation" (the other two being Takami-Musubi-no-Mikoto and Kammi-Musubi-no-Mikoto, per Washington State University). These three basically set the world into motion, and every other kami can trace their lineage back to them.

However, there's some debate about the chronology. According to "Shintoists in Restoration Japan (1868-1872)," older reports claim that he came into being after the creation of the universe, but the history presented by Hirata Atsutane changes that, saying that Amenominakanushi existed before either the heavens or the earth. As for why, the exact reasons aren't entirely clear. University lecturer Sasaki Kiyoshi explains that the change might have been made to more closely reflect Christian beliefs in a "creator deity," or to strengthen the power of the imperial bloodline. After all, the royal family was said to have divine origins, and tying them directly to the oldest deity in the universe – and the one who created everything, at that – would lend more credence to their right to rule.

Izanami and Izanagi

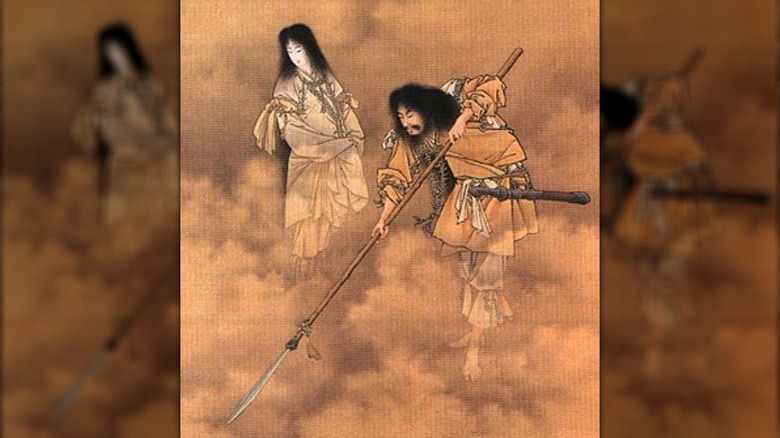

Like just about any other world mythology, Shinto has its own unique creation story, but the really eventful one has to do with the creation of Japan itself, as well as the two figures at the center of that story: Izanami and Izanagi. Known as "she who invites" and "he who invites," respectively, the two kami were ordered down to earth by their own divine superiors, per Britannica. There, they dipped a spear into the water and, pulling up mud from the bottom of the ocean that dripped off the tip, they created the first of the Japanese islands, called Onogoro-shima, according to the World History Encyclopedia.

On that island, they began the process of giving birth to the rest of the pantheon of gods; it wasn't a perfect process at first – they were far from satisfied by their first few offspring – but eventually, there was a whole host of new gods, as well as the rest of the islands of Japan.

Unfortunately, though, tragedy lay just past the horizon. In giving birth to the god of fire, Izanami was badly burned and died of her injuries. Izanagi mourned (violently, at certain points) and later made the journey down to the underworld to rescue the love of his life. But there were complications: Izanami had eaten food from the land of the dead and thus couldn't leave. With some shrewd bargaining with the other gods, an exception was made, albeit with a caveat: Izanagi couldn't look upon Izanami until she was ready to leave. Of course, things didn't go smoothly, and Izanagi couldn't wait. Izanami was furious and chased Izanagi from the underworld, thereby ending their relationship.

Amaterasu

Though there tends to be a lot of weight put onto origin stories and creation myths, when it comes to Shinto, traditionally, the most important figure isn't actually one of the kami tied to those narratives. Rather, the divine ruler of the celestial plane in Shinto is the goddess of the sun, known as Amaterasu.

Per the World History Encyclopedia, Amaterasu is the oldest daughter of Izanagi and Izanami, specifically born from her father's left eye while he cleansed himself in a river following his tragic trip to the underworld. Japanology adds that she also had two younger brothers – the moon god Tsukiyomi and the storm god Susanoo – and her lineage extended to Ame-no-Oshiho-mimi (her son and intended ruler of the earth). Following her bloodline even further, the imperial family of Japan also claimed her as their ancestor.

Despite being loved by all, Amaterasu didn't exactly have the easiest time, mostly on account of her brother Susanoo. After a rather unpleasant prank, Amaterasu locked herself in a cave, shutting herself off from the rest of the world for years on end. Without the goddess of the sun, the entire world was plunged into darkness as evil reigned. Things were going badly, to put it lightly, and the rest of the gods tried their best to coax Amaterasu out, to no avail. It wasn't until Amenouzume put on an exciting show that Amaterasu decided to take a quick look outside of her cave; at that point, Ame-no-tajikara-wo pulled her from her hiding place, and this age of darkness was ended.

Susanoo

To put it pretty simply, the storm and sea god Susanoo was the problem child of this divine family. The younger brother of the sun goddess Amaterasu, Susanoo was born as his father Izanami washed his nose in a river (via Britannica), and he went on to cause problem after problem. He mowed down forests, killed those who lived on earth, and ravaged the divine palace so thoroughly that the mountains themselves started to shake (via World History Encyclopedia). Amaterasu was understandably annoyed with her troublesome younger brother and banished him from the celestial plane. But his antics weren't quite done; he decided not only to kill a divine horse but also fling it through the roof of the palace, where it landed in front of his sister. Quite fed up, she retreated from the world in spite and hid in a cave, plunging the universe into darkness.

But as for a more fun story? Susanoo is also pretty well known for killing an eight-headed dragon. The beast was terrorizing some locals when Susanoo happened upon the situation and decided to help out. His solution? Getting the dragon drunk, then cutting off all eight of those heads while it was passed out. Maybe it's not the epic fight you'd expect to find in other mythologies, but it did the job, and Susanoo even pulled the sword Kusanagi from the tail of the dead dragon. He later gave the sword to his older sister as a form of apology, and it was eventually passed down to the imperial family.

Tsukuyomi

Though there were three children of Izanami, born after his visit to the underworld, Amaterasu and Susanoo are, undoubtedly, the more important figures of the three. That said, their brother, the moon god Tsukuyomi, didn't completely fade into obscurity. After all, there must be some sort of myth surrounding something as important as the moon, right?

Well, he's a big part of one particular myth. As summed up by Mythology Source, Tsukuyomi was married to his sister Amaterasu, and the two ruled together from the heavens. One day, they were both invited to a dinner by a food goddess, Uke Mochi; being too busy, Amaterasu sent Tsukuyomi to represent both of them. From there, things got messy. According to an article published by Michigan State University, after Tsukuyomi arrived, Uke Mochi began preparing food for the feast by turning into different entities and spitting the food out. As the ocean, she spat out fish, and as a rice field, she spat out rice. As a stickler for high-society-style etiquette, Tsukuyomi was disgusted by Uke Mochi's methods. And so he killed her.

Obviously, Amaterasu wasn't impressed, banishing her husband from heaven and branding him as evil. Though the myth explains the movement of the sun and moon – the two are never seen in the sky together, the moon left to chase after the sun eternally – it hasn't gained Tsukuyomi many followers. He's never been particularly popular and is largely looked at in a pretty negative light.

Inari

When it comes to the Japanese pantheon, there's ultimately a pretty big difference between deities who are important within the mythological narratives and those who are popular among real-life worshippers. After all, there's no contest when it comes to the most popular kami: the rice god (or goddess) Inari has tens of thousands of shrines across the country (via World History Encyclopedia). That's about a third of all Shinto shrines overall; for that matter, some Buddhist shrines are also dedicated to them (via Ancient Origins).

Being worshiped by so many different people across the country and across time, Inari has taken quite a few different forms – ranging from an old man hauling rice to a beautiful, young woman – though they're most commonly represented with the image of a fox. As for where and when this cult-like worship began, that's a hazier story. Legend says, though, that a man was practicing his skills with a bow and arrow when a white dove led him to a field of rice growing on Mount Inari sometime in the eighth century A.D. (though other sources say worship had started in the sixth century instead). There, he began honoring Inari, and given their place as the god of rice, their popularity spread like wildfire throughout Japan.

The really wild thing, however, is the fact that Inari's popularity hasn't diminished. Rather, it's grown. Even as times changed, Inari continued finding new followers. They eventually became tied to blacksmiths, making them important to samurai, and later came to represent commerce and prosperity on the whole – values that remain important today.

Tenjin

As a god heavily associated with learning and intellect, Tenman Tenjin is probably the kind of deity most people wish had been looking out for them whenever midterms and finals rolled around. Actually, that's not random speculation; per World History Encyclopedia, students in Japan do exactly that, leaving him offerings when exams are right around the corner.

But Tenjin's origins might be the more interesting thing here, since those origins perfectly demonstrate Shinto's tendency to incorporate figures from a wide range of sources into a sprawling mythology (via World History Encyclopedia). The real-life Tenjin was actually Sugawara no Michizane, a ninth-century administrator during the Heian Period. Michizane was born into a family of low standing, but his impeccable intellectual abilities led him to skyrocket through the official ranks, becoming one of the most powerful politicians in the country. Of course, that earned him quite a few enemies, who effectively accused Michizane of planning to depose the emperor and replace him. Their plan went off perfectly (at least at first), and Michizane was exiled; he never had the chance to see his family, friends, or home after that, dying in the early 10th century.

And then things got strange. Michizane's political rivals (and their family members) began dying under mysterious circumstances, as did the emperor who exiled him. Members of the plot that had accused him of treason were struck by lightning, and natural disasters ravaged the capital. "Sugawara no Michizane and the Early Heian Court" explains that people at the time were prone to ascribe these misfortunes to angry ghosts – in this case, Michizane's ghost. In an act of appeasement, they officially deified him, and Tenjin quickly became a popular Shinto god.

The Seven Lucky Gods

Religious beliefs in Japan aren't exactly the simplest thing to unravel. After all, aside from the native religion of Shinto, Japan has seen a good deal of influence from other countries, and so on the topic of religion, the country has also pulled from belief systems such as Buddhism and Confucianism. And according to "Shinto in the History of Japanese Religion," this has led to a really unique blend of beliefs that's held together, in a way, by Shinto itself.

The Seven Lucky Gods are a perfect example of that mix. The group is composed of Ebisu, Daikoku, Benten, Bishamon, Fukurokuju, Jurojin, and Hotei (via World History Encyclopedia). According to "Bacchanalian Revelry of the Seven Lucky Gods" (via UMMA Exchange), one hails from Shinto legend, three come from Buddhist and Hindu tradition, while the other three have their roots in Chinese culture. Fittingly, they're all their own distinct deities, differing in appearance, gender, and particular domain, which ranges from the god of workers to the god of wealth, the goddess of love to the god of war. Going through each of their domains would take quite a bit of time, so it suffices to say that, together, they represent prosperity and good fortune.

As such, they're heavily associated with the New Year, and it's said that they travel together in their ship – the Takarabune – which is loaded with treasures (including jewels and magic items). Legend says that those lucky enough to come upon them could even snag those riches for themselves. But if a magic hat isn't your style, then at the end of the year, you can sleep with a picture of them below your pillow to assure yourself good luck for the year to come.

Jizo and Kannon

If you were to travel to Japan, there's a good chance you'd see quite a bit of Buddhist symbolism and depictions of religious figures. With religion in Japan being a bit of a melting pot of various other religions (via "Shinto in the History of Japanese Religion"), it only makes sense to highlight two especially important figures originating from Buddhist practices: Kannon and Jizo.

According to the Japan Times, Kannon is known best for being the goddess of mercy, as well as a figure for motherhood. She's honored at temples all across the country, though plenty of people will also make pilgrimages in her name, seeking her kindness and the promise of immortality. Jizo, meanwhile, is most known for the prevalence of Jizo statues seen all across Japan, depicted as monks and often clothed in red hats and bibs (via KCP International). He's seen as a guardian figure, watching over travelers and children – more specifically, though, often the souls of dead children.

All of that said, Kannon and Jizo generally aren't referred to as gods, so to speak. Rather, they're both Bodhisattvas, figures in Buddhist tradition who decided to put off their own personal enlightenment in order to help others reach theirs.