De-Extinction: What Is It, How Might It Work, And What's The Problem?

Extinction? It happens. It's been happening for as long as there have been species roaming — or growing on — the Earth, ready and waiting to meet, mate, and finally, to die, but here's the thing: Humans have definitely made it much worse than it ever was.

According to the Smithsonian's National Museum of Natural History, years of studying the planet's fossil records have allowed scientists to determine the natural baseline for global extinctions. Over millennia, it turns out that for every one million species on the planet, one will go extinct every year. (Mass extinctions like the ones caused by asteroid impacts and a series of volcanic eruptions that destroyed a massive amount of marine life about 199 million years ago are something completely different.)

That's an almost unthinkable number of plants and animals that have vanished from this world of ours, and unfortunately, it looks like humans are going to be around to see even more happen. It's estimated that current extinction rates are thousands of times higher than they would be if the planet was just left to fend for itself, and that raises an important question.

Should humankind use their oversized brains and opposable thumbs to resurrect the species they've driven to extinction?

So, what is de-extinction?

De-extinction is basically taking a species that's gone extinct, and bringing it back. As if that isn't creepy enough, it's also called "resurrection biology."

According to an article published in the scientific journal Genes, the idea of de-extinction was first presented to the public as a serious scientific endeavor back in 2013. The first major project of an organization called Revive & Restore is going to be to bring back the passenger pigeon, a bird that once filled the skies of North America with their flocks of millions of birds. There were so many that the sound of an approaching flock was once described by a Potawatomi tribal leader (via Audubon) as sounding like "the trampling of horses," or "distant thunder."

That was in 1850, and the last passenger pigeon — Martha — died in a zoo in 1914. The species decline and extinction was caused by hunting, and the idea that we might be able to bring them back is a fascinating one. It's also a surprisingly complicated issue.

The passenger pigeon is kind of a cut-and-dried case: Humans killed them, and they disappeared. But what about other species? What if the passenger pigeon had, say, evolved thicker plumage, migrated to the North Pole, and set up residence there? Is the passenger pigeon still extinct, or is it just... different? What if two closely-related species interbreed to create a single hybrid species? Are the originals extinct? What makes a species, well, a species is at the heart of the issue.

De-extinction's origins in Nazi Germany

The idea of bringing back extinct species actually goes back to Nazi Germany and brothers Lutz and Heinz Heck. The directors of zoos in Berlin and Munich (respectively, says the U.S. Holocaust Museum), they became enamored with the idea of taking Germany back to a time when the landscapes were dominated by animals deemed to be better representations of the "purity" Nazis were striving for.

The Smithsonian says that they became obsessed with the idea of bringing back the aurochs (a massive type of cattle), a European bison called the wisent, and wild horses called tarpans.

And here's where things sort of separated. While Heinz Heck ended up in Dachau for his marriage to a Jewish woman and his opposition to Nazi doctrine (he was ultimately released), Lutz went all in — especially after meeting Hermann Goring. Goring dreamed of being able to ride through the forest, play dress-up, and "recreate" scenes from epic German poems, but he'd need extinct animals to get it really right... and that's where Lutz came in.

Lutz experimented with taking individual animals who exhibited the traits of the ancient species he was trying to recreate and doing something called "back-breeding" — which is basically breeding to try to reverse-engineer them to their earlier versions. He created Heck horses (pictured) and Heck cattle, and their descendants are still around today. They're not aurochs or tarpans, genetically speaking, but they're close enough for a Nazi who wants to use them in a full-scale roleplaying adventure.

Here's how cloning could work

There are a few different ways science is looking at using to bring back extinct animals, and according to National Geographic, one possibility is by cloning. They stress, though, that no one's going to be cloning a T-rex: In order for this one to work, scientists need enough DNA to reconstruct the genome of the extinct species. Given that DNA and genomes start to decay upon death, that limits the number of species that might be brought back via clones.

Beth Shapiro of the University of California Santa Cruz's Genome Institute explained (via the British Ecological Society) how it would — and wouldn't — work. In a nutshell, an egg cell with the nucleus removed would be "fertilized" with the information reconstructed from the extinct species. That would be implanted into a surrogate, and voila! In theory, an exact copy of the extinct individual would be born.

Experiments have been done, but there's a few problems — and they're big ones. For starters, getting the information needed to reconstruct genomes isn't just hard, in many cases, it's just not there anymore. Cloned individuals have also been shown to have severe health problems, and according to the University of Adelaide's professor and director of Ecological Modeling Corey J.A. Bradshaw (via The Conversation), it's just dumb.

Not only is it ridiculously expensive and wildly inefficient, but clones are exactly that: copies. Without genetic diversity, inbreeding would quickly destroy a species of identical clones.

Selective breeding is another option

Another option that's being looked at is exactly what Lutz and Heinz Heck were exploring in Germany in the 1920s and 1930s: back-breeding. It's called back-breeding because it's essentially the opposite of what's usually done. Take dogs. Breeders will often select which individuals they want to breed based on traits they want to see develop, whether it be a particular color, head shape, or temperament. They're making something new, but for de-extinction, breeders are making something old.

Beth Shapiro of the University of California Santa Cruz's Genome Institute says (via the British Ecological Society) that Heck's attempts at bringing back the aurochs is the perfect example. Modern cattle were selected for the aurochs-like traits they still had, like their size, the forward shape of their horns, and their incredible, mindless aggression. Over the course of generations, those — and other — traits get re-concentrated into an entirely new species that's just like the one that went extinct. In theory.

Shapiro adds that there are some difficulties here, too, starting with the fact that there has to be a currently-thriving species that's closely related to the extinct one, in order for scientists to have somewhere to start. Focusing on a narrow group of characteristics also increases the chance of inbreeding and associated problems, and finally, it's not clear if it's going to work. Shapiro stresses that Heck cattle — like the one pictured — are not aurochs.

Genetic engineering could work, too

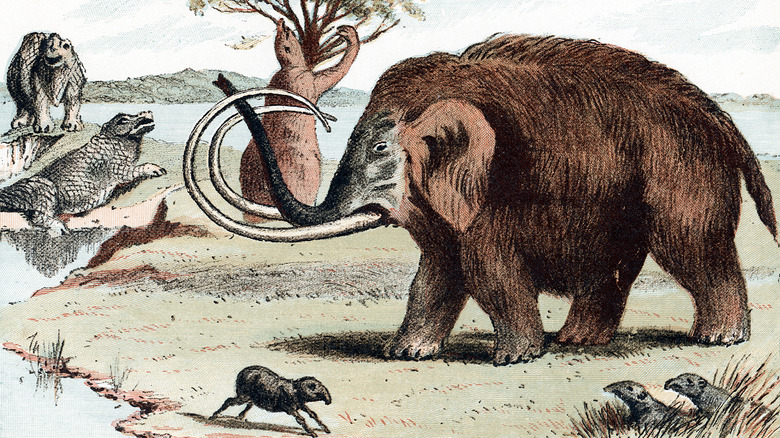

In 2021, a company called Colossal got $15 million in private funding for their project to resurrect the woolly mammoth. CNN spoke to the head of the project, George Church of the Harvard Medical School. "Up until 2021, it has been kind of a backburner project, frankly ... but now we can actually do it. This is going to change everything."

He described how they were going to do it, too — by genetically engineering an elephant. Using a gene editing tool called CRISPR, they were basically going to go into the genome of an elephant, and make an estimated 50 or so changes to the elephant's genes. Those changes would give the elephant all the characteristics of a woolly mammoth — like the shaggy coat and insulating layers of fat — while also allowing them to engineer out some undesirable traits. What are those? Tusks: Church says that their woolly mammoths won't grow tusks, as a way of keeping them safe from poachers.

From there, the edited cells will be grown either in a surrogate elephant or in an artificial womb. All going well, it would take about 22 months for a newborn baby mammoth to happen. But here's the million-dollar question: Is it a mammoth, or a genetically modified elephant?

The heartbreaking failure of the Pyrenean ibex

The Pyrenean ibex was a gorgeous creature that existed alongside ancient Europeans for generations — until, Forbes notes, the death of Celia in 2000. And this is where de-extinction comes in. Just months before she died, researchers had taken skin samples and put them on ice. After her death, a myriad of agencies got together to take those samples and create a clone.

They tried to create a lot of clones. Out of the 500 embryos created, five surrogate mothers ended up pregnant. One gave birth via cesarean, but the little mini-Celia died without taking her first breath. Initially looking healthy — she popped out kicking — she was unable to breathe due to massive defects in her organs. She was described as having a very short life that was spent entirely in "severe respiratory distress." That's horrifying, and according to National Geographic, study leaders weren't too fussed. They quoted Jose Folch (from the Center for Agro-Nutrition Research and Technology) as saying, "We are not especially disappointed for the death of the cloned newborn. We will try to improve the technology in order to increase the efficiency of the cloning process."

The baby ibex's fate wasn't uncommon, and cloned animals frequently die that way. Is it ethical to bring life into the world, knowing there's a good chance it will know nothing but pain? Mini-Celia's few agonizing moments mean the Pyrenean ibex has the dubious distinction of being the only species to go extinct twice.

De-extinction as a way to re-balance nature ... maybe

To paraphrase one of pop culture's smartest people: Science tends to focus on the logistics of whether or not something is possible, and the consequences sometimes come along after the fact. When the Polar Research and Policy Initiative looked at the question of resurrecting the woolly mammoth, they suggested that the major appeal here was the chance for humans to truly "play god." But, should they?

When CNN talked to the brains behind Colossal, the mammoth de-extinction program, they also talked to the skeptics about some of the reasoning behind the project. One of the ideas is that when woolly mammoths roamed the Arctic, they played an important part in maintaining the balance of the ecosystem. Not only did they graze, but their footsteps compacted the snow and ice, keeping the permafrost permanently frosty. That ultimately helped make the Arctic such a great place for carbon storage, and the idea is that by bringing them back today, they're going to step into that same role, and help slow the melting of the permafrost.

Evolutionary biologist Tori Herridge of London's Natural History Museum says that while that sounds great, it's really just a theory — and there's no evidence that it will (or did) work. Add in the fact that the ecosystem is a very different place than it was when woolly mammoths were around, and there are even more doubts.

How would these animals survive alongside people?

De-extinction is, at a glance, pretty cool. But it's also one of those things that the longer and harder you look at it, the less clear it becomes.

Kristiina Vogt is a University of Washington professor of ecosystem management, and in writing for the Center for Humans and Nature, she questioned just how on earth scientists could expect people to live alongside animals like the woolly mammoth, when they had proven again and again that they're incapable of co-existing with the animals currently struggling to eke out a living.

The planet's surface has changed a lot during the planet's existence, but humankind has had what she calls "an unusually large ecological footprint." Along the way, that footprint has managed to push species (like the wolves pictured) to the brink of extinction. When push comes to shove, people have historically made sure they have the upper hand, even if it means slaughtering vulnerable populations — like wolves — wholesale. Without thinking the whole thing through and deciding how to provide for an entire species, she foresees a future where these resurrected species have no place in the world other than in zoos. In a nutshell: If humans keep breaking the nice things they currently have, what's the point of getting them more nice things?

Should the focus be on saving endangered species instead?

Yale School of the Environment professor Paul Ehrlich and Yale Center for Conservation Biology coordinator Anne H. Ehrlich call de-extinction "a fascinating but dumb idea." At the heart of the problem was what they call a "misallocation of effort," and suggest that all the work — and money — going into bringing extinct species back would be better spent trying to save the species we have.

There are a few layers to this, and firstly, concentrating more on preventing extinctions instead of reversing them would have something of a domino effect. Habitats would be restored, pollution would decline, and maybe — just maybe — the planet would start getting back on track.

A piece written for PLOS agrees, suggesting that if de-extinction ever took off, the consequences would be catastrophic. In addition to not being able to predict what impacts extinct species would have on modern ecosystems, they also suggest that being able to snap our scientific fingers and resurrect an entire species could "reduce the moral weight of extinction," and turn the loss of an endangered plant or animal into something inconsequential.

The extent of environmental destruction could be insurmountable

David E. Blockstein of the National Council for Science and the Environment described how the current process of de-extinction isn't precisely bringing back extinct species, and he uses the passenger pigeon as an example. The plan to insert passenger pigeon DNA into band-tailed pigeons won't magically create passenger pigeons — instead, he calls them "a chimera." It might look like a passenger pigeon, but it wouldn't be one — and he adds that the chances it would act like one would be "essentially zero."

The Ecological Society of America agrees, saying that the chances that a species brought back from extinction would simply step back into old roles — particularly in an ecosystem that's been vastly changed — just isn't going to happen. What will happen, they stress, is that these old species will become invasive, and there's the potential that they'll destroy all the other plants and animals that have settled into the environment in the meantime.

They use the example of the common reed. Reeds were found across North America, and everything was fine. When Eurasian reeds — which looked pretty much the same, and filled a similar role in their native ecosystems — were introduced to North America, everything was not fine. The reeds became an invasive species that strangled North American wetlands, destroyed ecosystems, sent native plants and animals spiraling into extinction, and eradication efforts still cost millions of dollars every year. Bottom line? Re-introducing extinct species could break the planet's already-precarious ecosystems.

Should we use animals as surrogates?

When CNN talked to Colossal project leaders, they noted that they were looking at implanting genetically engineered embryos into elephant surrogates — and that opens a whole other can of ethical worms. Love Dalen is a professor of evolutionary genetics at Stockholm's Centre for Palaeogenetics, and explains it like this: Woolly mammoths are as genetically different from Asian elephants — the suggested surrogates — as humans are different from chimpanzees. Should one be made to carry the other? Weird, right? And that's not even getting into the fact that National Geographic points out that Asian elephants are endangered, too, with a population that's been on the decline for decades.

Dr. Barry Starr, a geneticist at The Tech Museum of Innovation, paints a dismal picture of the life destined for elephants chosen as surrogates (via KQED). The nature of experimental cloning or genetic engineering means there will be many, many failed pregnancies, and countless baby mammoths who are born stillborn, miscarried, or who die in infancy. Starr writes: "In this scenario, these intelligent, caring animals are forced to endure multiple failed pregnancies and many dead babies."

National Geographic has cited mounting evidence that yes, elephants do mourn the loss of their loved ones. William & Mary professor of anthropology Barbara King says, "I have no doubt that elephants grieve. We know these are smart and emotional creatures." So, what right do we have to turn them into baby factories?

De-extinction has happened naturally

So here's a weird story, and it's the one about the bird that evolved itself right out of extinction without any help from humans — or their opposable thumbs. It's called the white-throated rail, and according to research published by the University of Portsmouth and the Natural History Museum (via EurekAlert!), it lived on the small islands around Madagascar for a long, long time. Over the generations, a complete lack of predators meant that the birds gradually evolved to lose the ability to fly, and that ended up bringing an end to the species. Around 136,000 years ago, their island home flooded, and the white-throated rail went extinct.

Then, around 100,000 years ago, the waters receded and another group of rails settled down on the same islands. They, too, had no predators, and a study of the fossil remains shows that this second ground of birds evolved in the exact same way and lost their ability to fly.

The process of a species re-evolving after going extinct is called iterative evolution, says CBS. It's rare, but it does happen when an "ancestral species" is subjected to the same conditions and evolves the same way as predecessors to recreate a previously extinct species. Nature, it turns out, can do some incredible things when left alone long enough to do it.