The Ukraine-Russia Crisis Explained In Brief

The conflict between Russia and Ukraine has been going on for eight years since Russia annexed Crimea, as per Al Jazeera. Today, war may once again be on the horizon, this time not between Russia and Ukraine, but between Russia and the United States over the status of Ukraine. The media has portrayed the conflict as a clash between irreconcilable states.

The Russo-Ukraine conflict is much more complicated than a simple clash of nations. Ukraine itself is a diverse country of regions whose historical experiences shape their views of the conflict, Russia, and NATO. The crisis involves factions, historical enmities, geopolitical considerations, and most importantly, real people. Whether corporate and media oligarchs or vehement antiwar opposition in Russia, America, and Ukraine, conflicts and wars have consequences, and any explanation of the conflict owes them a fair explanation. Here is the Ukraine-Russia crisis explained in brief

The Minsk Protocols

The current Russo-Ukraine conflict revolves around the Minsk Protocols, which were signed in 2014 and 2015 to end the fighting in Eastern Ukraine, where Russian separatists have declared a breakaway state called the Donetsk People's Republic. So what does all this mean? According to the Minsk Protocols (via Reuters), both sides agreed to withdraw their forces and heavy weaponry from the front and allow humanitarian assistance. However, it does not appear that the agreements have been successfully implemented. Ukraine's former finance minister Oleksandr Danylyuk (via Politico) accused Russia of taking advantage of the ceasefire to bolster its troop numbers in the Donbass region, take control of regional governments, and bolster rebel forces through recruitment of locals and foreign mercenaries.

On the Russian side, President Vladimir Putin has refused to accept Russia's role as a party to the conflict. Russia has always denied the presence of any of its troops inside the Donbass region, although it has supplied the rebels with supplies and munitions, as per Reuters. Thus, Putin has argued, the Minsk Protocols cannot apply to Russia. Since he claims Russia has no soldiers to withdraw from Ukrainian territory and has never directly involved itself in any fighting, it is not a combatant. Furthermore, the Ukrainian army, Russia claims, has not held its promise to stop the fighting, as DW reports that clashes against separatists have continued despite promises for both sides to lay down their arms.

Historical considerations

The importance of this conflict begs the question: what is its basis? Here, it is necessary to understand Russo-Ukrainian relations from a historical perspective. Russian president Vladimir Putin himself, writing on the Kremlin's English website, stresses the close cultural ties and shared history between Russia and Ukraine. The inhabitants of both countries, he argues, are one people, whom Western European and American meddling has driven apart with a divide and conquer strategy,

Putin's analysis is correct -– to a point. Both nations trace their descent from the medieval Rus' state, which ruled over a vast swathe of territory encompassing modern Russia, Ukraine, and Belarus before it split into warring principalities. Both countries revere St. Volodymyr (via Encyclopedia of Ukraine), the patron saint of Ukraine and the man who Christianized the Rus' people. As Putin explains in his essay, when Orthodox Central Ukraine fell under Catholic Polish-Lithuanian rule, the Ukrainian Cossacks went to Moscow for protection. Ukrainians, in fact, were called "Ruthenians," the Latin term for the inhabitants of Rus' and the root of the demonym "Russian," until the beginning of the 20th century (today it refers to the Carpathian Rusyn people).

While Russia and Ukraine share a common history, Putin's argument has one major pitfall: As Britannica notes, Ukraine wasn't a unified state until 1991. Ukraine's different regions have significantly differing histories that have conditioned an array of attitudes towards Russia, some of which are hostile.

The nuances of Ukraine

While Vladimir Putin's argument may resonate in Russian-dominated areas of Ukraine and perhaps among Orthodox Christians, it falls flat in Western Ukraine. This area has plenty of reasons to distrust Russia. Western Ukraine, according to Holy Cross' Catholics and Cultures, was ruled from Austria and Poland, which left their mark on the region's language, culture, and religion. Although Ukraine is mostly Orthodox, Western Ukrainians adhere to Greek Catholicism, one of the Catholic Church's constituent bodies and a symbol of Ukrainian nationalism, per the Atlantic Council, which was ruthlessly liquidated under Soviet rule.

The hostility toward Russia centers around the Soviet Holodomor genocide of 1933. According to HREC Education, this engineered famine murdered between 3 and 10 million Ukrainians and Russified their lands with Russian colonists from other areas of the USSR. So, although the Holodomor was not a Russian nationalist genocide, Russian nationalism and Soviet atrocities are closely tied in the Ukrainian mind today. Business Insider notes that Russia's rejection of responsibility and Putin's past pro-Soviet statements only exacerbate these views. The complicity of the Russian Orthodox Church, today a major Putin ally (via Forbes) in the liquidation of Ukrainian Catholicism, completes the trifecta of distrust (via the Wall Street Journal). This does not, however, mean that there is wide support for war.

The NATO issue

As one can see, the Russo-Ukraine conflict is in part conditioned from a tug-of-war in Ukraine between those that have always looked to Western Europe, and those that have been more loyal to the Russian Orthodox world. Now throw NATO into this volatile mix and you have a setup for a major war.

According to The Conversation, Ukraine has shown interest in joining NATO since 1992, a move that 54% of Ukrainians support (via IRI). Membership would make Ukraine part of NATO's "collective defense" doctrine, forming a deterrent against future Russian encroachment. But more significantly, according to the Military Times, the United States and NATO would be able to deploy missiles there that would inevitably be aimed at Moscow. With sectors of the U.S. establishment calling for war with Russia (via the Hill) over allegations of 2016 election meddling, Russian has been on guard. Should a war break out, the U.S. would be legally obligated to intervene against a fellow nuclear power.

Russia, per the Military Times, has declared Ukraine's NATO membership the "red line." However, The Conversation notes that Vladimir Putin has offered to "stand down" from Ukraine should NATO withdraw its offer of membership. This, of course assumes Russia's good faith, since Putin's actions will be a barometer for the security of other Eastern European states that suffered under Soviet policies of Russification and communism.

Will Russia stop at Ukraine?

Radio Free Europe notes that one of Russia's major casus belli for a possible attack on Ukraine is the protection of diaspora Russians in Eastern Europe. This stance has set off alarm bells in the Baltic region, where Latvia and Estonia have clashed with their own Russian minorities. According to Foreign Policy, the Baltic states have provided the Ukraine most recently with surface-to-air missiles to counter Russian airpower. Their reasoning is simple: Avoid a repeat of Soviet brutality during World War II. Finno-Estonian writer Sofi Oksanen (via the Guardian) recounts through her novels that the USSR ethnically cleansed parts of Latvia and Ukraine, and as in Ukraine, replaced them with Russian colonists. In fact, according to On Latvia, Latvians had nearly become a minority (52%) in their own lands by 1989. Although the USSR — not Russia — committed atrocities, there is nothing to stop Russia today from capitalizing on the colonists' descendants' presence and claiming them as its own.

The George C. Marshall Center notes that today, the Baltic countries face severe Russian pressure, particularly over the status of substantial Russian minorities in Latvia and Estonia. These descendants of Soviet colonialism, per Radio Free Europe, comprise around one quarter of these countries' populations. Thus, the Baltic states will be watching Ukraine very carefully, because what happens there may very well be a predictor of their own futures.

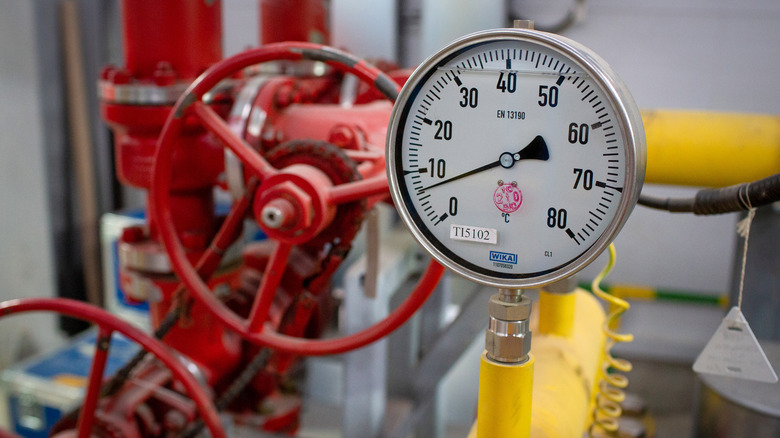

Europe and the gas problem

The Russo-Ukraine conflict inevitably would involve NATO intervention, but it is unclear if many Western European NATO states share Eastern Europe's opposition to Russia. France 24 notes that the countries who are also members of the EU must balance their NATO obligations with their dependence on Russian energy. Russia provides about 35% of Western Europe's oil and gas supply.

At the center of the conflict of interest is the Nord Stream 2 pipeline — a joint project with Russia and a consortium of European oil and gas companies. War risks destroying their investments. Since the pipeline can only be canceled if Russia's Gazprom energy company and all consortium members agree, they have every reason to lobby for a peaceful solution to the Ukraine problem and prevent any sort of hot war.

Russia ultimately holds all the cards in this particular situation. According to Statista, countries such as Finland, Bulgaria, and Macedonia rely almost exclusively on Russian gas. EU heavyweights Germany and Italy get around half from Russia, Poland about 40%, and France around a quarter. Thus, a Russian gas shutdown in the middle of winter during a war would have disastrous social consequences barring an alternative source. And as American Secretary of State Anthony Blinken discovered (via Reuters), Germany and other European countries are not willing to take that risk.

The Chinese wildcard

As the conflict between Russia and Ukraine threatens to go global, observers have speculated on the attitude of the third major power involved: China. According to DW, China has maintained an official position of neutrality regarding the conflict. However, their statements suggest that the Chinese Communist Party sees the Ukraine conflict as a chance to strengthen ties with Russia and isolate the U.S.

The U.S. government has urged China to oppose any Russian expansion in Eastern Europe. According to DW, the Chinese government has asked all parties to remain calm and not escalate tensions any further. So far, so good. But foreign minister Wang Yi added that Russia's concerns "should be taken seriously," probably a nod to the stance that Ukraine's NATO membership should not come at the expense of Russian security.

China's position signals its willingness to tacitly support possible Russian moves in Eastern Europe in return for support on the international stage. China's image has tarnished following revelations that it has thrown members of its religious minorities into concentration camps (via Radio Free Asia) and other human rights abuses leading to boycotts of the Winter Olympics (via BBC). Vladimir Putin, however, has been a reliable pillar of support for Beijing and referred to the boycotts as "[politicizing] sports for ... selfish interests" (via DW). The Chinese–Russian rapprochement does not bode well for the NATO alliance should war break out, since it would possibly confront two nuclear powers with expansionist interests into the U.S. sphere of influence.

Who wants war?

The Ukraine conflict has threatened to spill into an all-out war that has powerful proponents in Russia and the U.S. Time Magazine notes that the U.S. and Russia have traded accusations of warmongering. Western media tends to focus on Vladimir Putin, but the Russian president, although autocratic, still faces political pressure from pro- and antiwar factions that will sway his decisions in Ukraine. Their identities are hard to define from current English-language reports, but a letter from Russian academics (via Al Jazeera) accuses Putin's Russian corporate and media allies of pushing war despite public opinion against it. This mirrors the situation in the U.S.

In the U.S., the neoconservative movement has been the principal cheerleader of war. NBC's Think notes that this lobby, which includes the powerful defense industry, has enriched itself tremendously from Middle Eastern regime-change wars while civilians and U.S. soldiers have paid the price in blood. Although officially the Biden Administration has opposed war, the European Institute of International Relations notes that President Joe Biden, like predecessors George Bush and Barack Obama, has historically aligned with neoconservatives in support of America's Middle Eastern campaigns. Because of the president's past stances, populist Republicans and antiwar Democrats have come out guns blazing against the possibility of yet another war.

The U.S. public is opposed

According to The Atlantic, antiwar sentiment has united Americans across political lines in opposition to the Beltway war lobby. Leaders on both sides of the aisle are in agreement with not sending troops to the Ukraine. Pew suggests that this is reflective of American public opinion, which is more concerned with ballooning national debt, widening economic inequality, mass illegal immigration, and culture wars at home. Foreign policy did not even register.

Also, the numbers don't lie, with 73% of Americans (via the Koch Institute) opposing any war with Russia and, instead, wanting the government to focus on domestic issues. "The United States has no vital interests at stake in Ukraine and continuing to take actions that increase the risk of a confrontation with nuclear-armed Russia is therefore not necessary for our security," said Will Ruger, vice president of Research and Policy at the Koch Institute. "After more than two decades of endless war abroad, it is not surprising there is wariness among the American people for yet another war that wouldn't make us safer or more prosperous."

Furthering the point, the Santa Barbara News-Press asks: Why should U.S. troops need die needlessly abroad to defend Ukraine's border when they should be focusing on their own borders?

Many Russians are also opposed

Although Ukrainians may not always consider Russia a brother country, many individual Russians have opposed war against Ukraine on this exact premise. Russia's antiwar movement doesn't seem to be as strong as in the U.S., but surveys allow analysts to extrapolate somewhat. According to the Carnegie Endowment, at least 23% of Russians support Russo-Ukrainian friendship. Among Russia's 18-24 cohort, the people that would serve and die, sympathetic attitudes to Ukraine top 66%. A positive attitude towards Ukraine is a good marker of opposition to war, as interviews of ordinary Russians suggest.

Fortunately, many Russians do not think war is even a prospect. The BBC notes that Russians either have faith that Vladimir Putin will negotiate or at least cave to public opposition. Several interviewees referred to Ukrainians as "brothers," suggesting that at least some sectors of the Russian public have no interest in killing their fellow East Slavs, with whom they share a history, religion, and culture.

According to Al Jazeera, the Russian antiwar movement has not named particular warmongers, perhaps fearing a backlash from Putin or one of his allies. But an open letter from academics accuses the Russian media of stoking state-level tensions that do not exist between ordinary Russians and Ukrainians. Russian citizen Tatyana Volnova captured this attitude in an echo of many Americans' frustrations. In a war, the "sons and grandsons" of the Russian public will fight and die.

What about Ukraine?

While American and Russian attitudes to the conflict have dominated headlines, oft-forgotten yet most important is the opinion of the Ukrainian people, who have the most to lose in a war. Their voices fly in the face of common wisdom that Ukrainians (not the government) want U.S. intervention against Russia. According to Ukrainian academic Yuri Sheilazhenko (via Breakthrough News), Ukrainians generally do not want war. There is no appetite for it, and around 40% of the Ukrainian population would refuse to fight or evade conscription.

Sheilazhenko acknowledges Russian encroachment but also accuses the White House and American media of "sabre-rattling" and provoking Russia. He suggests Kiev and Moscow should solve their problems bilaterally by strictly implementing the Minsk protocols –- that is, withdrawing all foreign forces from Ukrainian soil. Once tempers have cooled, negotiation can recommence. Sheilazhenko's proposal places Ukraine's oft-ignored interests at the center of the conflict, a position that has received support from Ukraine's Catholic establishment.

The Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church is historically no friend of Russia thanks to the Soviet persecution of the 1940's. Yet, per Catholic magazine Crux Now, Patriarch Sviatoslav Shevchuk has refused to back the Ukrainian government, calling it a "pawn" in a U.S.-Russia conflict that Ukraine has nothing to gain from. Shevchuk does not appear to trust the political processes, as he has instead appealed to Pope Francis to visit Ukraine immediately (via Crux Now). Since even the Orthodox patriarchs of Russia and Ukraine respect the pope's moral authority, Shevchuk believes his presence on its own will stop the war and get the parties back to the negotiating table.

A negotiated solution is in everyone's interests

Yuri Sheilazhenko's interview highlights an important disconnect between politicians and people. When politicians and armchair generals start wars, civilians and soldiers suffer and die. In Sheilazhenko's view, negotiation is the only way forward and always preferable to death, no matter how justified a war may seem. But as Patriarch Sviatoslav Shevchuk mentioned in Crux Now Magazine, Ukraine is a geographic crossroads. In fact, according to Time, one interpretation of the country's name comes from the East Slavic term for "borderland." Its position places it right in the firing line between Russia and the U.S., and it is unlikely that either side will want the country in the other's sphere of influence.

Fortunately, there is a solution that could work if all parties accept it. The Quincy Institute suggests that Ukraine become a neutral country (like Switzerland). The Donbass would return to Ukrainian control as a Russian-speaking autonomous region and perhaps set a precedent to solve the problem of Crimea as well. Such an arrangement would preclude Ukrainian NATO membership but would guarantee its independence from Russia and shelter it from entangling alliances that have led to its current predicament. Currently, there is still a chance to make such an idea work. According to The Conversation, Vladimir Putin has claimed that he will back off Ukraine if NATO blocks the country's entrance to the organization. If he is being sincere, this is a golden opportunity to spare Europe from another horrific bloodbath.