The History Of Babylon Explained

The first civilization on the planet arose in a region called Mesopotamia, in what is generally today's Iraq. As described by Britannica, the name "Mesopotamia" comes from Greek and means "the land between the two rivers," referring to the Tigris and Euphrates. It was in Mesopotamia that the domestication of plants and animals first allowed for the development of fully settled lifestyles with people living in cities.

Of the cities in Mesopotamia, none is more famous than Babylon. Yet the reasons for its fame are more biblical than historical. Second to Egypt, Babylon appears more in the Old Testament than any other historical ancient civilization. It even makes appearances in the New Testament's Book of Revelation — chapter 17, verse 5 — as a place synonymous with corruption.

Alternating between building its own empires and being subject to others, Babylon was a key city of antiquity that these days continues to be cloaked in a semi-mythical mystique. Let's unpack Babylon's history and explain why this fascinating city on the Euphrates was so important.

Babylon was so old that no one really knows when it was founded

Imagine being so old you have no idea when you were born. So it is true for Babylon. The World History Encyclopedia states that Babylon first entered the historic record in the 23rd century B.C. By that time, it already existed as a minor city of Akkadian-speaking people along the Euphrates, perhaps a port for traffic passing up and down the river. There is one religious text called the Weidner Chronicle that claims that the city was founded by Sargon the Great, who is best known as the founder of the world's first empire, per World History Encyclopedia. However, this claim has been consistently disputed, although Sargon apparently did some construction within the city that helped it grow in prominence.

Much of the reason why we don't know much about the earliest history of Babylon is that the original city was destroyed and water levels in the region have risen since those remote times. As a result, what archaeologists have uncovered in terms of ruins and the like actually date to about a millennium later than when the city is supposed to have been first founded. However, artifacts from early Babylon that were found outside the ruins indicate that the city was probably established by the Amorites during the Third Dynasty of Ur, which dates from approximately 2094 to 2047 B.C. Britannica.

Marduk is key to understanding Babylon

Before proceeding further into the epic history of Babylon, it is important to mention Marduk. Who is Marduk? Marduk was the patron god of Babylon whose story passes through all of the city's history, as explained by the University of Pennsylvania. In Babylonian mythology, Marduk created the world after slaying Tiamat, the embodiment of the ocean. Tiamat also stood for the female principle, while Marduk represented the male principle. As Babylon grew in power, strength, and therefore influence, Marduk became more central in Babylonian religion. So much so that outsiders associated him with the Greco-Roman god Jupiter (equivalent to Greek's Zeus) as the highest of all gods. Still, his exact nature has always been debated; some assume he was a sky god, while others believe he is tied to agriculture. In any event, he was subject to cult worship in Babylon with a ziggurat — the Etemenanki — being dedicated to him. All those who sought to rule or rule from Babylon needed to show respect to Marduk.

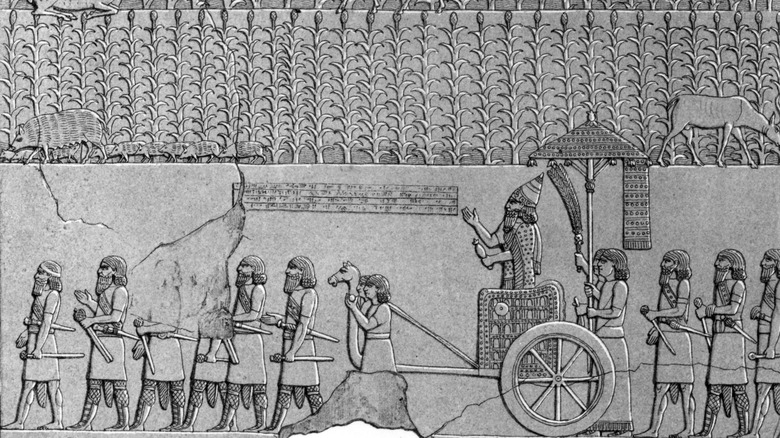

Hammurabi put Babylon on the map

Babylon first burst into history after the establishment of an empire, known as the first Babylonian Empire — or Babylonia. According to National Geographic, Hammurabi reigned from 1792 to 1750 B.C. after subduing the various rival city-states of Mesopotamia. He was the sixth king of the Amorite dynasty, as described by the World History Encyclopedia. Hammurabi had a grand vision of a united Mesopotamia, and through sly diplomacy and conquest, he united all of the region under his rule. Simultaneously, he also built up Babylon by establishing new temples to Marduk, making the city one of the largest and most beautiful in the world.

Hammurabi, however, is best known for his law code. While this code is not the earliest in history, it was very influential to the point where it is in all social studies curricula. Its "eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth" principles were the essence of retributive justice; nobles and commoners were treated equally under the code, and it applied the principles of justice to all people. It even gave some protections to women, such as the right to sue for divorce against abusive husbands as well as punishing those who committed perjury with death. Hammurabi's Code attempted to establish an eternal order through writing by creating clear laws that everybody had to obey. No doubt this was Hammurabi's attempt to make his state durable for eternity. Unfortunately, it didn't work.

Babylon was left in ruins for rebelling

Hammurabi proved to be the only capable king of Babylonia. As described by "Ancient Mesopotamia," his son Samsu-iluna immediately experienced troubles that he was incapable of handling. He was faced with massive rebellions, and by putting them down he so denuded the land that he created an economic catastrophe. Towns were deserted, and within eight decades after the great king's death, Babylonia was reduced to only the area surrounding the city itself. In essence, it became what Babylon controlled prior to Hammurabi's reign. So weak did Babylonia become that it was invaded, first by the Hittites in 1595 B.C. and then by the Kassites, as explained by the World History Encyclopedia. The Kassites renamed the city Karanduniash, and the meaning of the name is still unknown.

It seemed that Babylon was destined to become an obscure city, but eventually, a new power arose. The powerful Assyrian Empire took control of Babylon from the Kassites. However, the Babylonians were tired of being swapped between empires like trading cards. So in 703 B.C., during the reign of the Assyrian King Sennacherib, Babylon revolted. In the details provided by "Sennacherib's Babylonian Problem," Sennacherib tried first to install various friendly rulers to lord over Babylon, including his own son. But in the mayhem of insurrection and conquest, his son was handed over to Assyrian enemies and likely killed. Ultimately, Sennacherib conquered Babylon in 689 B.C. and razed it.

Babylon was rebuilt on the bones of Sennacherib

The story of Babylon did not end with its destruction by Sennacherib. In fact, Sennacherib was assassinated by his own sons, something that is mentioned in the Hebrew Bible. As explained by the World History Encyclopedia, it was assumed that the murder stemmed from the king's razing of Babylon. Indeed, Babylon was a religious center, and as noted by "Sennacherib and the Angry Gods of Babylon and Israel," the king destroyed important temples to Marduk. This act was generally considered to be beyond the pale. Meanwhile, this event was noted in the Book of Kings as being coordinated by the hand of the Hebrew god. Of course, the cynical and probably correct view is that Sennacherib was a victim of the court power politics between his many sons.

In any event, even though Babylon had been destroyed, the city was too special to remain dust. Esarhaddon, Sennacherib's son and successor, distanced himself from his father and committed himself to rebuilding the ancient city back to its former glory. His efforts are etched in the ruins of Babylon in paeons of his piety to Marduk and how he rebuilt the city. The Babylonians for their part would revolt again, but the Assyrians never again destroyed the city.

Nebuchadnezzar II brought Babylon to its greatest glory

Over time, the Assyrian empire declined and was so weak that by 625 B.C., Nabopolassar, the governor of Chaldea, seized control of Babylon. According to National Geographic, this new king of Babylon made an alliance with the Medes and sacked the Assyrian capital of Nineveh in 612 B.C. Thus was the Neo-Babylonian Empire founded. In 605 B.C., Nabopolassar's son, Nebuchadnezzar II (sometimes Nebuchadrezzar) became king. Nebuchadnezzar had ample military experience fighting the remnants of the Assyrians and the Egyptians. In fact, his name is a regnal one after a Babylonian warrior king of the 12th century B.C., making him Nebuchadnezzar II, which means "Nabu, watch over my heir." Nabu was the Mesopotamian god of wisdom. Under his rule, Babylonia took control of the entire Fertile Crescent, reaching its greatest height of power. To celebrate his feats and cement his rule, he turned his attention to cementing his reign and glory by renovating and beautifying Babylon.

Nebuchadnezzar II's Babylon was considered one of the most beautiful cities

Under Nebuchadnezzar, Babylon reached new heights of fame and beauty. A National Geographic analysis of Ancient Babylon maintains that there was plenty for an ancient tourist to gape at in the city. Using funds from his conquests, Nebuchadnezzar enlarged the city so that it encompassed over three square miles. He then built landmarks that were legendary in their day. First, there was the brilliant blue Ishtar Gate, which was the main entrance into the city. Then there was the restored Temple of Marduk. Also were the Hanging Gardens, which in Herodotus' reckoning was one of the Seven Wonders of the ancient world.

During this time, Babylon was perhaps the largest city in the world. The Babylonians saw their beautiful city as its natural center, and it was a city of learning and culture. However, it was also seen as a dangerous place for those who were subdued by it. The ancient Hebrews equated Babylon with sin, hubris, and impiety. One of the most famous stories of the bible, the construction of the Tower of Babel, is believed to be based on the Great Ziggurat of the city — the Etemenanki temple tower dedicated to Marduk.

Nebuchadnezzar II is also an important figure in Judeo-Christianity

As previously mentioned, Babylon figures are prominent in biblical tradition, and Nebuchadnezzar II is one of its most prominent villains. As explained by the Jewish Virtual Library, a common practice of the ancient Mesopotamians was to deport conquered peoples to lessen the potential for rebellion. The Assyrians, for example, famously deported ten of the tribes of Israel, thus making the legendary "Lost Tribes of Israel." Elsewhere, Nebuchadnezzar did this to the Kingdom of Judah after its conquest in 597 B.C. by deporting its elites into Babylon. This period became known as the Babylonian exile.

The exile transformed the ancient Hebrew religion into the first iterations of Judaism. It is likely that during this period, the Torah took its final form. It is also during this time that much of the books of the prophets were finalized, including the Book of Daniel. As described in National Geographic, this text contains a famous story where a mysterious hand appears in the court of Babylonian King Belshazzar and writes words upon the wall. These were later deciphered by the exile Daniel, who prophesized the downfall of the Babylonians to the Persians and the Medes.

The Persians conquered Babylon by moving the Euphrates

The Persians did indeed conquer Babylon under Cyrus II, who became known as "Cyrus the Great." According to National Geographic, he took Babylonia in 539 B.C. after the Battle of Opis near the Tigris. During this time, the Persians laid a clever plot to take Babylon, as described by the World History Encyclopedia. The city's walls were considered impregnable, so Cyrus had the waters of the Euphrates diverted, thus lowering the water and making the task of taking the great city more manageable. The soldiers simply waded through the waters, all resistance collapsed, and the city fell without a fight.

Cyrus entered the city for general festivities. As explained by "Babylonia Under Achaemenian Rule," Cyrus ingratiated himself to the Babylonian populus by honoring Marduk — something that the Neo-Babylonian rulers had forgotten or neglected. In essence, this gave Cyrus the legitimacy he needed to add King of Babylonia to his list of growing titles, and he easily took control of the entire Fertile Crescent. Never again would there be a native Babylonian empire. And in the aftermath of Cyrus' conquest, he allowed the Jews who were held in Babylon to return to Judah. That is why in Jewish tradition, Cyrus is considered a liberating hero.

Babylon became a center of learning under the Persian Empire

The Persians held Babylon in high regard. Even though it was prone to rebellion, it served as an administrative capital for the Empire. As a result, the city maintained its high status and reputation. Under Persian rule, the Babylonians continued to practice their traditional polytheistic religion, and the city generally remained in the same physical layout as it had been since the renovation work of Nebuchadnezzar. However, as pointed out by "Babylonia Under Achaemenian Rule," life fundamentally changed in Babylon under Persian rule. Babylon became an increasingly diverse city, and the written language — which had been traditional Sumerian cuneiform — was slowly replaced by Semitic Aramaic. As a province of the Persian empire, Babylonia was heavily taxed with 30 tons of silver annually and provided subsidies for the Persian army.

Still, despite these burdens, the World History Encyclopedia maintains that Babylon continued to flourish, with people far and wide admiring their mathematicians, astronomy, and cosmology. Indeed, it is believed that Babylon influenced Greek learning. For example, Pythagoras' famous theorem is thought to have derived from Babylonian mathematics. This is not to say that the Babylonians completely kowtowed to their Persian masters. In fact, they revolted against the Persian King Xerxes I, who put down the revolt after laying siege to the city. According to Britannica, the resulting suppression in 484 B.C. destroyed the city's fortresses and temples; even the statue of Marduk was torn down.

Babylon slowly fell into ruin after the conquest of Alexander the Great

The Persian Empire was destroyed by the Macedonian conqueror Alexander the Great in 331 B.C., per World History Encyclopedia. Like the Persians before him, Alexander was awed by Babylon's history and reputation, and he ordered his troops not to sack or tamper with the city and its inhabitants in any way. In fact, he made plans to rebuild the city's ziggurat to be even grander than it was before.

However, this was not to be, and Alexander died in 323 B.C. in Babylon. His generals then agreed to the Partition of Babylon, which divided up the empire. It didn't go peacefully, and a series of wars erupted to decide who would inherit his immense empire. These conflicts, known as the Wars of the Diadochi, were bad news for Babylon. The territory was invaded, taken, and then reconquered several times between the different commanders. By the time it was done, Babylon was a shell of its former self.

Babylon slowly decayed, and by the time the Parthian Empire took control of the area in 141 B.C., it was a virtual ruin. Several hundred years later, at the time of the Muslim conquests of the 7th century A.D., the once-great city of Hammurabi and Nebuchadnezzar was gone. Babylon had left the realm of history and entered the kingdom of legend.

19th century archaeologists rediscovered Babylon

Babylon might have remained a legend if it were not for archaeologists. The most notable of these was the German Robert Koldewy, who was seeking out sites from the Bible to determine the historical truth of the Old and New Testaments, as explained by Britannica. Beginning in 1897, he selected and dug at the reputed site of Babylon and made some awe-inspiring discoveries. He first found that the city had been rebuilt multiple times, most notably under Nebuchadnezzar. He also found the ziggurat dedicated to Marduk and clues leading to the discovery of the Ishtar Gate. According to National Geographic, the gate itself was reconstructed and put on display at the Pergamon Museum in Berlin. Koldewy also believed he found evidence of the Hanging Gardens of Babylon, although this particular claim has been disputed.

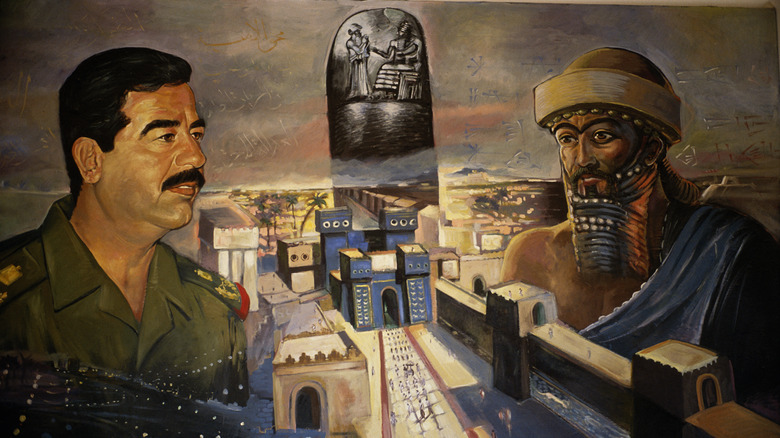

This groundbreaking work was continued through the 20th century. The Iraqi autocrat Saddam Hussein was obsessed with connecting to Babylon's illustrious past, building a common national story for Iraq, and proving himself to be Nebuchadnezzar II reborn. So much so that he spent millions to reconstruct the ruins, according to Atlas Obscura. It is telling of Hussein's hubris that his palace features stone reliefs of the dictator's face mixed freely with Babylonian iconography.

Ephemeral architects aside, Babylon is a story of the ages. This was confirmed in 2019 when it was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site that "inspired artistic, popular and religious culture on a global scale."