Extinct Plants That Would Wreck The Earth If They Were Alive Today

The true rulers of Earth are not humans but plants. According to the World Economic Forum, by mass, all of humanity makes up just 0.011% of life on Earth. By contrast, plants make up about 82% of Earth's biomass. We barely pay them any attention in our daily lives, but they're everywhere, spending every moment quietly engineering Earth's environment, harvesting solar energy, and maintaining the atmosphere. There would certainly be trouble if the plants decided to go rogue. Disconcertingly, they've actually done this at least once in Earth's history.

Plants have played a role in more than one of Earth's mass extinctions. The first was an ancient event known as the Oxygen Catastrophe. 2.4 billion years ago, according to a paper published in Nature Communications. The early ancestors of plants filled the atmosphere with so much oxygen so quickly that it left a thick band of rust in the planet's geological record. This created today's atmosphere, but it also killed a lot of Earth's life at the time.

Life on Earth is a precarious balancing act. Each plant and animal species keeps those around it in check. Take one thing away from its environment and place it elsewhere, and you'll easily find yourself with an invasive species. Humans cause these all too often, with infamous plants like Kudzu and Japanese knotweed currently strangling entire ecosystems. But there are many plants from Earth's ancient past which could easily be far more damaging to our modern world.

Ancient Stinging Nettles

Stinging nettles are found all across the world, but their history goes back roughly 50 million years, into the Eocene geological epoch. According to Britannica, Earth was a warm world back then, and forests blanketed the entire planet. All of Earth was a buffet for giant herbivores, and some plants learned how to defend themselves.

Urticaceae, the nettle family, are well known for their stings. Touching them causes sharp, burning pain and sometimes welts, notes Health.com, with some species much more severe than others. A study published in the American Journal of Botany found that ancient Urticaceae had already evolved stinging hairs, known as trichomes, 48.7 million years ago. These were a lot like the ones seen in the world today but, with the task of fending off some of the largest mammals to ever walk the Earth, these ancient nettles may have needed much more potent stings. They may have been more like Australia's infamous Gympie-Gympie stinging tree, known for its agonizingly painful stings that can last for months. The idea of a world filled with such merciless trees is not a pleasant one.

These aren't the only painful plants in Earth's history though. Stinging trichomes are mercifully rare, but a study published in the journal Plants found that other plant species have learned this trick before. A clade of flowering plants has evolved stinging hairs at least 12 times in the past.

Paleocene Fabaceae

As everyone learned in school, a meteor strike was what killed off the dinosaurs, as per Live Science. Sixty-six million years ago, the impact created the Chicxulub crater and changed the Earth forever, for both plants and animals alike. Accumulating Glitches talks about how plants had to adapt after the meteor impact plunged the world into years of perpetual winter. The plants that fared best were small, grew quickly, and were able to adapt to the changing climate. A paper in Systematic Biology explains how one family of plants that did especially well after the impact was the Fabaceae.

You'll know them better as beans. Fabaceae now comprise the world's third largest family of flowering plants, farmed for crops like soy, lentils, and peanuts. The ancient ancestors of beans originated during the last days of the dinosaurs, with a study published in the Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society finding that they evolved around the time of the Chicxulub meteor.

These ancient beans from the Palaeogene weren't too different to the ones seen today. The fruit of Leguminocarpum Olmensis, reported in a 2021 study in Communications Biology, looks a lot like something you might find growing in a vegetable garden. But they lived in a harsh world, where they needed to be tougher. Adaptable and fast-growing, they had to fight to survive. Placed into a much more comfortable Earth, they could easily run amok and become a dangerously invasive species.

Ancient Carnivorous Plants

The idea of giant carnivorous plants, large enough to devour a human, has captivated people for decades. Despite featuring in plenty of fiction though, there's no evidence they ever existed. While the reality would have been very different to "Day Of The Triffids," it's still not impossible there may have been extinct carnivorous plants which could feed on more sizeable prey.

According to a paper published in Current Biology, plants first evolved a way to digest prey by repurposing genes from roots to absorb nutrients from prey instead of soil. As the Journal of Experimental Botany notes, carnivorous plants have evolved more than once, with pitcher plants being a common type. The largest pitcher plant found in the world today is Nepenthes Rajah, native to Borneo, with traps large enough to catch rodents (though they usually just collect droppings). It's not hard to imagine a long-extinct ancestor species, able to feast on larger animals. Without any fossil evidence though, this is pure speculation.

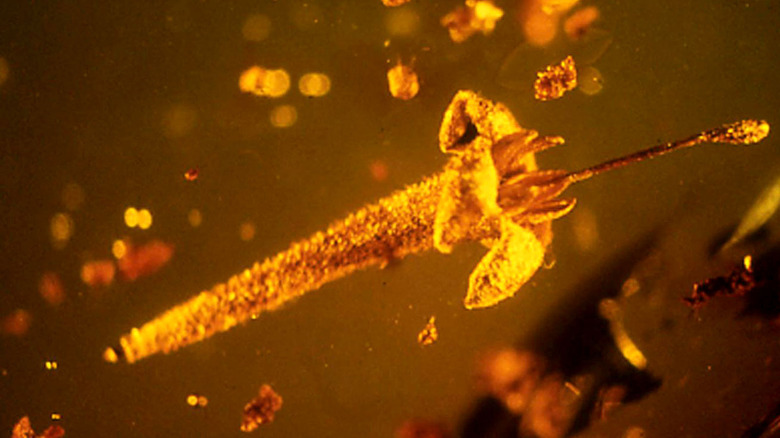

The oldest confirmed carnivorous plant fossil, named Roridula, is much more recent. Detailed by New Scientist, it's a fossil of just two leaves trapped inside a nugget of amber. Dating back to somewhere between 35-47 million years ago, these ancient leaves are covered with hairs, not unlike the sundews that still live in Earth's marshlands. Unlike any sci-fi ideas of deadly plants though, little Roridula was no killer. At least, not unless you happened to be an insect.

Strychnos Electri

The world's oldest intact flower is another fossil preserved in amber. Discovered by George Poinar at Oregon State University, Strychnos Electri is an ancient flower 20–30 million years old. It was also very poisonous, as virtually all members of the plant genus Strychnos are. After all, the plants share their name with strychnine, a potent alkaloid toxin.

Strychnos Electri has a much longer history though. They likely evolved in tropical forests during the late Cretaceous. In a world full of dinosaurs, plants at this time were going through a revolution. They'd only evolved flowers 150 to 130 million years ago, filling the prehistoric world with color but, more significantly, they'd also started to evolve deadly toxins. These attractive but lethal plants may have helped to bring down the dinosaurs.

It's now well known that the dinosaurs were starting to die off even before the Chicxulub impact wiped them out for good, and the dramatically named Biotic Revenge Hypothesis gives a possible reason why. Published in the journal Ideas in Ecology and Evolution, it centers around the idea that the dinosaurs started to die off around the same time that plants started producing deadly toxins. If dinosaurs were unable to learn which plants not to eat, they may have been slowly poisoned en masse long before the meteor impact. And if the herbivores died out, so too would the carnivores that hunted them. The hypothesis is still unproven, but the idea that plants helped kill the dinosaurs is a compelling one.

Gondwanan Maidenhair

While plants were starting to produce flowers, all of Earth's land was a single huge continent named Gondwana. Evolving on that continent was an ancient ancestor of the maidenhair vines sometimes kept as houseplants today. A study published in PLoS One found that this extinct ancestor was growing 110 million years ago and was distributed all across Gondwana. As the vast landmass started to break apart into the continents of today, this ancient maidenhair ancestor began to evolve into a variety of different species, several descendants of which are still growing vigorously now. Unfortunately, this made things worse for us.

Maidenhair vines, also known as Muehlenbeckia, are part of the Polygonaceae family of plants, known for its vigorously invasive species, according to a study in the journal, Taxon. One prominent example is Japanese knotweed, a name which strikes dread into the hearts of ecologists after these plants laid waste to entire European ecosystems (via Harper's Magazine).

These plants are even more troublesome when they keep each other company. A paper published in the American Journal of Botany explains how Polygonaceae are not just noxious invasive plants, but they become even more dangerous when they hybridize with each other. If the ancient original plant was somehow reintroduced today, it could easily be disastrous, able to hybridize with all of the other existing Polygonaceae species and making ecological damage much, much worse.

Sphenophyllales

Some of the worst invasive plant species in the world are vines, according to a study in the Journal of Tropical Agriculture, but the vines alive today are probably like kittens compared to some of their long-dead ancestors that used to grow in the forests of Earth's ancient past. Sphenophyllales were among the plants growing on those ancient forests, an extinct order of plants that included rugged vines. These plants were prolific, growing everywhere in the Triassic period (250-200 million years ago), during the early days of the dinosaurs. A study published by the Bulletin of the National Science Museum in Tokyo found that while Sphenophyllales may have been alive during the Triassic, they first grew even earlier, in the Late Devonian period, which Live Science notes was from 419 million to 359 million years ago.

In other words, these plants were older than the dinosaurs and grew on Earth for over 100 million years. They survived deadly events in Earth's history like the the Late Devonian Extinction and even made it through events that were lethal to other plants, like the Carboniferous Rainforest Collapse and the Permian-Triassic Extinction that devastated Earth's wetland forests.

As a paper in Nature Communications notes, the calamitous extinction event at the end of the Permian period may have wiped out most of Earth's animals, but many plants barely even noticed, carrying on as if nothing had happened. In fact, some plants may have been partially to blame. If these hardy survivors were alive today, already potential culprits in mammalian extinction, how much better would humanity potential fare?

Permian Microalgae

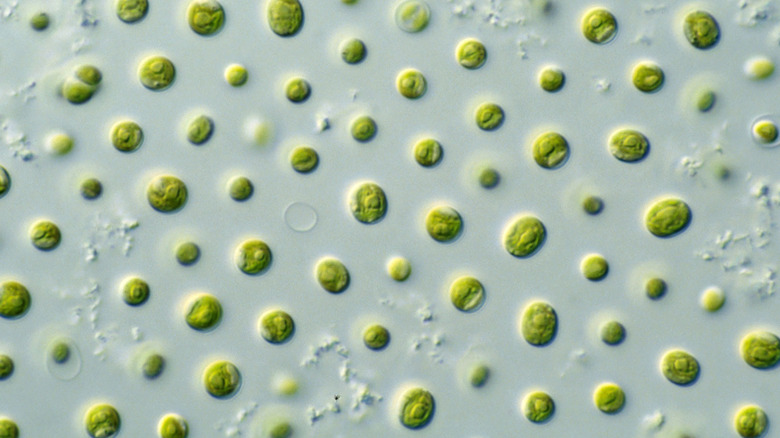

The end of the Permian period saw the worst extinction event in our planet's history. Known as the Great Dying, it wiped out most of Earth's biological families about 250 million years ago (via NASA). Countless species vanished, lost in the blink of a geological eye. The cause? Sudden, severe climate change. At least, that was what started it. Aquatic creatures were hit hardest by widespread deoxygenation of the water, as an article in Nature Communications explains, and the culprit was algae.

Microalgae aren't technically plants but, as a paper in PNAS explains, similar algae were the original ancestors of all land plants. They can also be extremely harmful when Earth's climate falls out of balance, forming thick algal blooms in water. These are double trouble for aquatic ecosystems, filling the water with toxins while sucking up all of the oxygen, simultaneously poisoning and suffocating aquatic animals. This is exactly what happened worldwide at the end of the Permian period. A region known as the Siberian Traps saw some of the most intense volcanic activity Earth has ever known. This caused outgassing, belching vast amounts of carbon dioxide into the air, acidifying the oceans and feeding huge algal blooms. A study published in Nature Communications explains how these events were followed by algal blooms that ruined freshwater ecosystems for hundreds of thousands of years.

Perhaps the most concerning part, though, is that those Permian microalgae weren't too different to the microalgae that still live on Earth today. And our atmospheric carbon dioxide levels keep rising, as NOAA reports.

Glossopteris

During the Permian period, all of Earth's land was once again a single supercontinent, as far back as 299 million years, called Pangea, and growing all across Pangea were trees named Glossopteris. A paper published by the Journal of the Botanical Society of Bengal describes how Permian fossils are full of the leaves from Glossopteris trees. They grew absolutely everywhere in the Permian world. After the rainforests of the Carboniferous period collapsed, Glossopteris evolved to take their place, quickly taking over spaces where other trees once stood.

Pangea had weather that humans would find quite unpleasant. A study in Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B describes how Pangean weather had baking hot summers and icy cold winters. The interiors of the vast continent were arid, while the coastal areas suffered vicious monsoons. All of this shows how Glossopteris could easily become an invasive species too, if it were to end up in the changing climate of our modern world.

Trees can easily become invasive species. In 2014, the Global Invasive Species Database compiled a list of 100 of the World's Worst Invasive Alien Species. Five of the most troublesome species on that list are trees. The world around us is suffering from rampant deforestation and desertification, while climate change causes increasingly extreme weather. All of this isn't too different to the conditions in which Glossopteris thrived during the Permian period. If it found its way into the modern world, it wouldn't be long before it started to cause chaos.

Lepidophoios

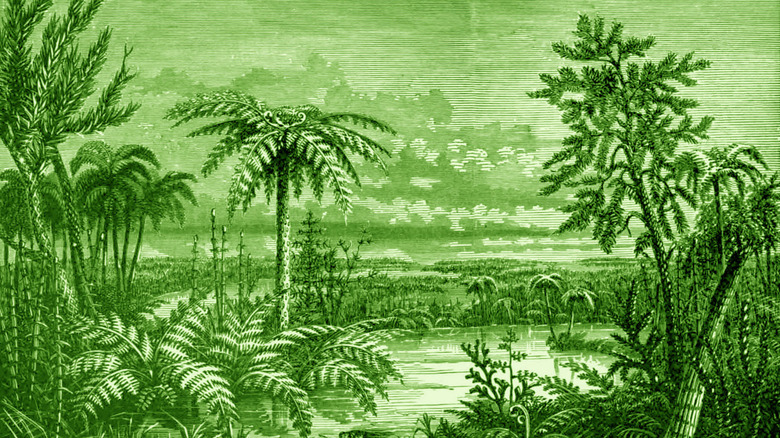

Around 359 to 299 million years ago, plants truly took ownership of Earth. According to UCMP Berkeley, it was a hot, humid world, and the first true forests blanketed the land. Few animals had left the seas, with the few land dwellers including giant amphibians the size of hawks extremely large in size, as per JSTOR Daily.

Many plants grew in coastal swamps, not entirely unlike the tropical mangroves today. Others like Lepidophoios thrived in a variety of habitats, as an old paper from the Journal of Ecology explains. Lepidophoios was one of the more adaptable trees of the Carboniferous period. Early trees like these were known as scale trees, because of the appearance of their bark, with its eerie similarity to snakeskin.

During this time frame, there were so many plants growing on Earth that the air was rich with much more oxygen than today. This made the world a dangerous place. As National Geographic explains, that oxygen allowed insects and spiders to grow to enormous sizes, but far more dangerous were the wildfires. A study published in the journal Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology talks about how wildfires were intense and widespread back then. With air so rich in oxygen, even a single lightning strike could cause vicious firestorms, hot-burning and hard to extinguish. All of this was no setback to trees like Lepidophoios, which rapidly grew back, taking advantage of the newly cleared land.

Aneurophytales

Around 419 million to 393 million years ago, Britannica notes our lungfish ancestors were still learning how to walk, and plants were still learning how to plant. The early vegetation became Earth's ecosystem engineers, controlling life and death. According to the Devonian Plant Hypothesis, detailed in a paper in Earth-Science Reviews, all the environmental changes which happened during this time frame were caused by the plants that began covering the land.

Aneurophytales were some of the world's first ever vines and bushes, according to UCMP Berkeley, owing their success to their thick, woody stems. The book, "Nature Through Time," explains that plants had only recently evolved wood, which would have protected them from the harsh sunlight of the ancient skies. These early ancestors of trees were utterly unlike any plants today. They had no leaves, and no root systems, instead growing thin hair-like structures called rhizoids. Springing directly from their stems, the plants would use these rhizoids to cling to whatever they were lying on.

According to Smithsonian, three of modern North America's worst invasive species are English Ivy, Japanese honeysuckle, and Kudzu. These vines grow fast, blanketing anything in their paths with woody stems and clinging rhizoid hairs. If aneurophytales were brought back into the world today, they could be exactly the same, sprawling across everything in their path like eldritch botanical horrors. Even worse, with no roots, they'd be hard to remove, and with no leaves, animals might completely ignore them instead of eating the vines to keep them in check.

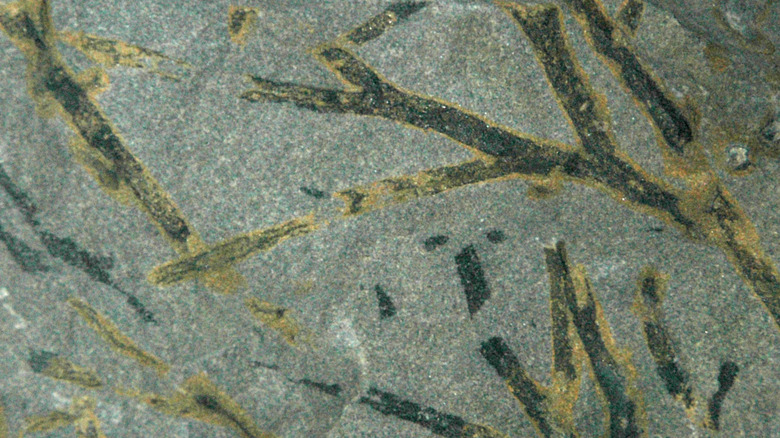

Proterocladus Antiquus

The oldest known ancestor of modern plants, Proterocladus antiquus, lived an astonishing 1 billion years ago. Reported in Nature Ecology & Evolution in 2020, this discovery forced palaeobotanists to rethink a few things about plant evolution, because this ancient seaweed was growing hundreds of million years earlier than anyone expected. No matter how much we learn about ancient plants, they can still find ways to surprise us.

As a seaweed, Proterocladus antiquus isn't really a plant but a kind of algae, specifically, a variety of green algae known as a chlorophyte. This period of Earth's ancient history is known as the Precambrian, back when most life on Earth was little more than a collection of drifting microbes in the shallow sunlit seas, leaving the microfossils found today. With no animals in the ocean to eat them, Proterocladus antiquus could easily have grown prolifically, forming grass-like blankets on the ancient seafloor.

Chlorophytes still live in the seas today, with some growing into fine, thread-like green filaments just as they did a billion years ago. Unfortunately though, seaweed can become invasive just as easily as the plants that grow on land. A study published in the Journal of Evolutionary Biology discusses an invasive chlorophyte known as Caulerpa Racemosa, which is damaging ecosystems in the Mediterranean sea, like some kind of underwater kudzu. It seems like maybe even the oldest of Earth's plants could be an invasive species if they were reintroduced to the modern world.