What The American Road Trip Was Like 50 Years Ago

Vacations as they are today were not always part of the American pastime. As a matter of fact, most Americans wouldn't travel much beyond their immediate town, city, or region until after the economic boom years post-WWII. Incomes were increasing, and paid time off was becoming more commonplace. As The New York Times reported, "The popularity and affordability of cars were instrumental in the cultural shift. From 1945 to 1965, the number of private motor vehicle registrations almost tripled, from about 26 million to nearly 75 million." The Atlantic – in an interview with Richard Ratay, author of "Don't Make Me Pull Over!" — noted that WWII had a psychological effect on a generation of dads who came home from war overseas and were anxious to be on the move and see new places. Airline costs were still prohibitive for most people in the country, so families in the '60s and '70s took to the road.

President Dwight D. Eisenhower signed into effect The Federal Aid Highway Act of 1956, which began the construction of the major highway systems. Between 1956 and the early '90s, 45,000 miles of highway were built across the nation (via U.S. Army). It allowed raw materials and products to be moved across the country cheaper by way of semis, gave farmers and rural areas an economic boost, and made commuting to city jobs possible (via ArcGIS StoryMaps). And, of course, it made the American road trip just that much more feasible.

Not all highways were actually completed

Sheryl Stein shared some of her memories about road travel in the '70s with The Washington Post, and she talked about the detours that were required by her dad in order to bypass unfinished interstates: "The detours were not usually entertaining and sometimes ended poorly ... Most of the time, we ended up driving down local streets where the weathered old houses presented a very different picture than the well-manicured suburb we'd left behind." The decay of these small towns was only beginning. The creation of the interstates — while being a boon to some rural areas — also gutted most others economically, as travelers chose the faster interstate routes over the smaller state and county roads that passed through town (via ArcGIS StoryMaps).

Even to this day — while they are few — there are still true gaps in highways. For instance, Interstate 69 was meant as a highway that would connect Mexico with Canada and was nicknamed the "NAFTA Super Highway," yet in the area between Dyersburg and Millington — running through Tipton County — in Tennessee is a gap. The highway is not yet complete and has been in discussion for years (via The Covington Leader). However, gaps, now, compared to gaps in the '70s are nowhere near the inconvenience they used to be. There are other highways and byways can easily get a car from one part of I-69 to the next.

Nothing but the radio (and possibly 8-track)

Before the digital music revolution where endless music from our smart phones can be played on our car stereos by wire or wireless means took place, there was a long history of audio systems in automobiles starting with the simple idea of a radio in a car. In the '60s and '70s, however, pre-recorded music looked much different within the scope of automobile features. According to Hagerty Magazine in a multi-part series on obsolete car audio, "[W]hile it's well-documented that the first car with a factory 8-Track was the 1966 Mustang ... I see references to Mercedes as having Becker radios with cassettes beginning in 1971. Most sources list the general envelope of cassette adoption as 'mid-1970s.'" With this in mind, imagining a road trip 50 years ago would probably involve a family fighting over radio stations or over which 8-Track tape — or, more likely, cassette tapes by the latter '70s — would emit music into the cab of the station wagon.

Meanwhile, the landscape of AM/FM radio was going through its own shifts. By the mid-1970s, "FM radio accounted for one-third of all radio listening but only 14 percent of radio profits ... Stations began tightening their playlists and narrowing their formats to please advertisers and to generate greater revenues. By the end of the 1970s, radio stations were beginning to play specific formats, and the progressive radio of the previous decade had become difficult to find" (via "Understanding Media and Culture").

Maps were made out of paper

Geographical Information Systems (GIS) were in their infancy in the 1970s. The Arizona Department of Transportation put a photo on their site of a man standing on an enlarged, multi-sheet 15-by-17-foot geographical map in 1977 that allowed them to plant more detailed data on along the roads and highways like traffic statistics (via ADOT). This is the beginning of the technology and data mining that would be the base of GPS and our smart phone map apps. Yet in the 1970s, people who traveled used paper maps to get around the country on their roadtrips.

These maps were hand-scratched into plastics before they were printed. According to an article from the United States Geological Survey (USGS), "In the 1970's, scribing on coated mylars and color separation using peelcoats became the method for producing maps and would not change significantly until the introduction of computers." Updated information on construction and traffic and even speed traps were never known in the minute like they are now via Google Maps or Apple Maps. It took time to produce maps every year. One cartographer, Anthony Stevens, who still makes maps today, talks about how hand-made maps are still beneficial: "[Companies] ... like Google rely on that base data so you can have your electronic version. If that base data is not being developed then your electronic data is going to get out of date as well" (via ABC Australia). All technology begins with human work.

55 mph national maximum speed limit

Did you know that Sammy Hagar came up with "I Can't Drive 55" because of a nationwide speed limit of 55 mph enacted in 1974 by Richard Nixon? It was done by Nixon as an attempt to save 200,000 barrels of oil a day after the Arab oil crisis of 1973. The pushback on the law was tremendous, with everything from rock songs to abolishing the law becoming a platform for the Republican Party in the 1980 election (via The Spokesman-Review). Needless to say, the law was not popular, but it was sustained at least until 1987 when Congress allowed states to reset the speed limits within their borders. Still, because proponents of the law said it lowered total fatalities, the law remained on the books until 1995, according to History.

These proponents were not completely wrong either; one study showed that there was a "3.2% increase in road fatalities attributable to the raised speed limits on all road types in the United States." This percentage amounted to 12,545 deaths and 36,583 injuries between 1995 and 2005 (via American Journal of Public Health). So while people in the '70s and '80s, including Sammy Hagar, couldn't handle driving 55, they probably should have.

Drive-thru windows were the newest fad

Dave Thomas, the founder of Wendy's, noted, "The drive-in used to be real popular, and there are more cars on the roads but there are less drive-ins." Thomas recognized that, which made him put a service window on his original Wendy's store and every store after. Burger King and McDonald's followed in 1975. Households, by this point, had two income streams and longer commutes due to urban development. More money was spent on eating out, nearing 40% of food dollars spent (via Serious Eats). Not only did this change family eating habits, it also changed the kinds of food that were served by these restaurant chains, as well as interior car features. Food like Chicken McNuggets were created around this time, and flat-folding glovebox doors became standard in vehicles (via AAA).

Convenience became the name of the game when it came to eating on the road. Instead of pulling into a drive-in, people wanted to minimize their wait time and maximize their travel efficiency. It paid off because in 1970, alone, people spent $6 billion on fast food, and by 2000 that number rose to $110 billion, according to a review of "Fast Food Nation" (via The New York Times). The drive-thru window ease became the grease on the profit wheel of these restaurants.

Automobiles broke down more often

There is an old adage, often among older generations, that things are no longer built to last, and while this can be true it wasn't always the case with vehicles in the 1970s. As a matter of fact, "the average age of vehicles on the road in the United States stretched to a record 11.1 years in 2011," according to The New York Times. It is far more common today to find online classifieds selling used cars that have 150,000 to 200,000 miles on them which the owners note still have a lot of life left (via The New York Times). They gained this information from vehicle registrations and sales. In contrast, cars back in the '60s and '70s were would only go to 99,999 miles before flipping back to zeroes, and the popular wisdom of the time was driving cars beyond 100,000 miles was potentially a minefield of issues.

Richard Ratay spoke of the improvements involved in roadtrips now as opposed to ones in the 1970s: "I remember my dad packing up all sorts of tools and extra belts and fuses, because you didn't know when you were going to break down on a family vacation. It wasn't a question of if you were going to break down — it was almost a given that you were" (via The Atlantic). But even if the cars of the '60s and '70s were built as well, people would not keep them beyond 100,000 miles.

Some station wagons had rear-facing third-row seats

Perhaps one of the most unique elements of roadtrips in the '70s was that members of families in some station wagons would have a whole different experience of road travel than the rest of the family. This was because there were cars with rear-facing seats that we just don't see anymore — often out of safety. As John Cushman, Jr. wrote in The New York Times in 1999, "That third seat was called the way-back not only because of its location in the car, but also because it described the view that the kids saw out the wagon's rear window. No matter where the family traveled, the occupants in the third seat could see the way back."

Compared to the minivans that pushed out the station wagons over the years, the ratio of seat belts to exits was more desirable and any kid could fold up that third row seat inside a station wagon whereas minivans and SUVs involve the removal of a whole row of seats in order for more cargo to be placed in the back. However, sometimes safety ends up trumping convenience according to Cushman, Jr. and thats probably as it should be (via The New York Times).

Seatbelts were not popular

Many of us have heard stories from parents and grandparents about the magical time prior to seatbelts being a compulsory feature of driving. These would include tell of parents strong-arming children so they wouldn't slam into dashboards and free-wheelin' babes riding between parents in the front seat. The Detroit Bureau reports that "[b]ack then, only 10 to 15% of occupants buckled up." It got so bad that by the late '60s, the national death toll on highways was nearing 50,000 deaths a year. However, the rage against compulsory seatbelts was seemingly particularly strong in the 1970s considering the Interlock Seatbelt Fiasco.

Engineers designed an interlock seatbelt with two sensors inside that required every person in the front row of the car to buckle up before the car would even start. After the car started, one could unbuckle, but, according to reports at the time, this didn't happen often. However, the rush of this new technology into cars without working out bugs — and the general disapproval of being told what one can and cannot do — led to an uproar by American drivers. The outcry was so bad that Congress passed a law soon after outlawing the interlock seatbelt feature (via The Detroit Bureau).

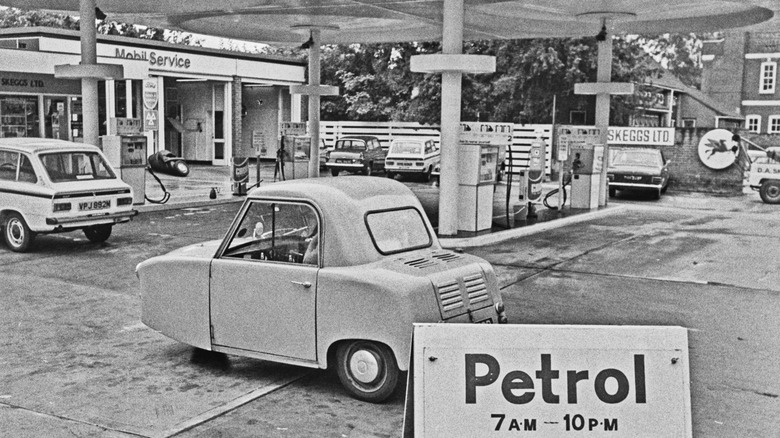

Gas stations were sparse and meant for ... gas

When the modern driver thinks of gas stations, they think of full service convenience stores with bathrooms and all of the snacks one can load up in their arms. Yet this is actually a fairly recent invention. In the '70s, gas stations were for gas ... and maybe a Coke machine. No bathrooms, no other amenities, no food and drink options, just gas. According to the University of Houston, "By 1970 America had over 200,000 gas stations. Then things began changing. By 1990, half those stations were gone, and their number keeps falling." They delineate gas station from service station, which is more in line with what is common today.

Even if one could find a gas station, by 1974 it didn't mean that there was always going to be gas after the Arab Oil Crisis that hit. An example of the difficulties this led to is shown in the Baltimore Sun. "Seething drivers waited in queues, some five miles long, for hours in ... 'bread lines on wheels,' hoping to fill up; too often, stations ran out of gas. Fights broke out, station owners were threatened and some began toting guns." This was just in cities. Just consider what might have happened with people stuck in the middle of nowhere with little gas to go around.

Gas was cheaper until 1973

The fear of being left stranded because of a lack of gas was not the only one that took over the hearts and minds of those after the Arab Oil Crisis of 1973-'74, but also the fear of not being able to afford the price of gas. Gas prices in the 1960s and 1970s hovered below 50 cents per gallon — that is, until the Arab nations that made up OPEC (Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries) put an oil embargo on the United States due to their support of Israel in the Yom Kippur War during 1973. Not only was the gasoline limited in amounts, but the price of gas skyrocketed, sending American drivers into panics (via South Bend Tribune).

That was the last time anyone saw gas prices that low. By the end of the embargo in March of 1974, the price per oil barrel had quadrupled, and President Richard Nixon had instituted fuel rationing and the national speed limit in response to this crisis (via Britannica).

Hitchhiking was still a thing for a bit longer

Hitchhiking is such a novelty to most people today, but back in the 1970s, it was a legitimate way to travel across the state — or even across the country. Statistician Bill James noted in an episode of "Freakonomics" that hitching "drove itself out of existence. Basically nobody hitchhikes anymore ... And the real danger was not hitchhiking; it was the fact that you had a certain number of random crazy people who will hurt you." That's something that hasn't changed with time, and people have become a bit wiser to that, so "eliminating hitchhiking doesn't ... do anything to change that. So, it was a social change that protects the individual" (via The Atlantic).

But sociologist David Smith notes, according to Vox, that it is the increase in overall car ownership (especially extending into the lower classes) that probably had the biggest impact on hitchhiking, not so much the fear of violence. Also, with the increase in interstates being built across the country in the '60s and '70s, there were less opportunities for hitchers to thumb a ride in small towns and on smaller roads where a car could just pull over. Interstates are more policed, and people seldom stop on them until they get off on an exit. It seems that hitching largely died out with enhanced roads and cheaper cars.

Rest areas were more important than they are now

When talking about gas stations selling only gas and not much more, the next question on everyone's mind is: where did people stop to use the restroom? It's in the title: rest stops. They still exist to this day, but they end up being more of a stop gap between convenience stores or for those emergency bathroom uses. What many may not know is that rest stops were part of the original Federal Aid Highway Act of 1956 which started the construction of the interstate highway system. It was a 90/10 funding process where the Federal government mostly funded their creation, but the state had to pay the other portion and design and build the rest stops themselves (via Washington State Department of Transportation).

By the 1970s, developers started to design rest areas "in forms that drew on regional imagery such as tipis, oil rigs and windmills and designed buildings that reflected the architectural heritage of indigenous people." Eventually, many of the sites where rest stops and rest areas that were built attempted to engage the local culture and landscape, as reported by Rest Area History.