Rules That Members Of The Mongols Bike Gang Have To Follow

The Mongols Motorcycle Club was established on December 5, 1969 in Montebello, California, a city just east of East Los Angeles. Per their archived official website, which appears to have been last updated in 2010, there were 15 members in the original club, and within five years, there were additional chapters in Los Angeles, San Diego, Bakersfield, Long Beach, San Gabriel Valley, and San Fernando Valley.

The Mongols described their presence in Southern California as a "stronghold" and note that "[a]t the time and even now there were really no other 1%er clubs co-existing in these areas." According to the website One Percenters Bikers, this term came to be in response to statement made in 1947 by the American Motorcycle Association that 99% of motorcyclists are law-abiding citizens; clubs such as the Hells Angels, the Outlaws, and the Mongols refer to themselves as the other "1%."

The Mongols club is named for Genghis Khan's Mongol army, which the website characterized as "small in numbers with a lot of heart" who "dominated and decimated their enemies." Like other motorcycle clubs, the Mongols have a variety of rules they have to follow.

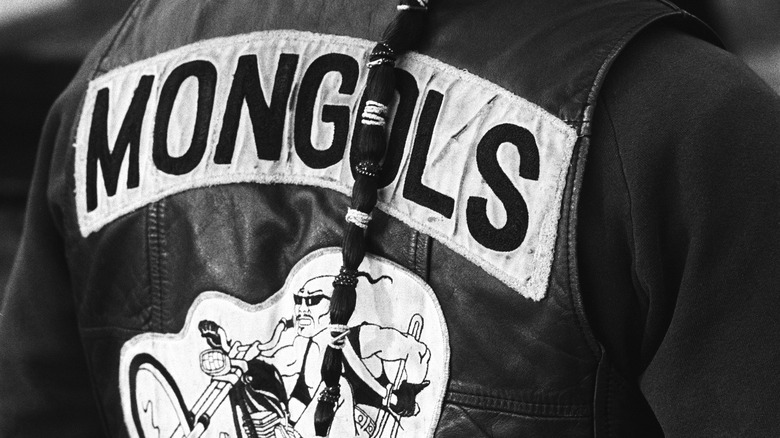

Patches are all important to Mongols club members

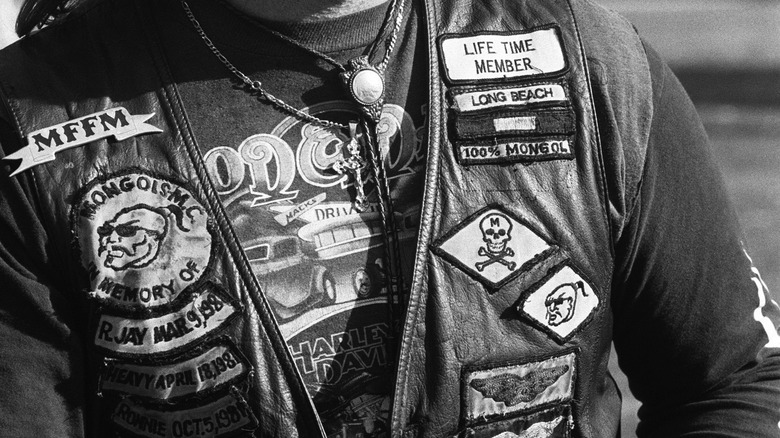

As with other motorcycle clubs, members of the Mongols value the patches they wear on their jackets and vests that announce their membership as well as indicate the rider's rank and achievements within the organization, as reported by Hot Cars. Per One Percenter Bikers, the patches are in the club colors of black and white, and the main patch consists of a drawing of Genghis Khan riding a Harley Davidson motorcycle.

Other possible patches include one designating the rider as a "one percenter" biker, and one reading MFFM, which stands for "Mongols Forever, Forever Mongols." According to a report by CNN (available on YouTube), newly accepted members receive patches upon their acceptance into the club. The main back patches, or rockers, are earned in three steps, starting with the bottom one that indicates the location of the club, followed by the middle Genghis Khan patch, and finally the top Mongols patch, indicating full Mongol membership.

Mongols patches were protected by the First Amendment

The Mongols member interviewed by Lisa Ling for CNN, identified only by his first name, Dave, said of the patches, "For me, it's total commitment to this club. I'd be willing to take a bullet for a brother and a brother who'd be willing to take a bullet for me." When Ling replied, "People have fought and died for the patches," Dave confirmed her statement (per YouTube).

In December 2018, the club was convicted of racketeering and conspiracy, and one month later, in a ruling called the first of its kind, a jury ruled to strip the Mongols of their trademarked logo. As reported by NBC News, prosecutors had been attempting to take down the Mongols for over a decade, with Assistant U.S. Attorney Steve Welk saying members were "empowered by these symbols that they wear like armor." In February 2019, also reported by NBC, U.S. District Judge David O. Carter declined to approve the jury's decision, citing constitutional protections against excessive fines and for free speech. The Mongols trademark remained.

Mongols members sometimes use a secret code to communicate

The Mongols even have their own coded language that they use to communicate with one another, according to Hot Cars. The site compares the code to that used by the military and notes that club members use them to communicate when other methods are unavailable or when they want the content of their conversations to remain private. One example given is after a Mongol member committed a murder, the club called a Code 55, instructing members to hide all affiliation, including stopping wearing their vests and patches, carrying weapons, or interacting with law enforcement.

In her story on the Mongols for CNN (available on YouTube), journalist Lisa Ling asked a tattoo artist if anyone who wanted one could get a tattoo of a "Mongol head," referring to the head of the official, trademarked Mongol symbol. The artist laughed and said no; there was a whole chain of command necessary in order to obtain the right to get such as tattoo. The aforementioned Mongol member Dave joked that the tattoo would be "cut off" of anyone who got one without permission. When Ling pressed him, he said he would "Ask you to remove it or cover it up ... nicely." When Ling asked "What if I refused?" Dave repeated, "Nicely."

Mongol tattoos must go through a 'chain of command'

As the CNN interview with Lisa Ling (available on YouTube) continued, the tattoo artist, who was also a Mongols member, shared that another rule for prospective members is that they must "be a breadwinner to be in this club." He went on to explain, "That's one of the first questions we ask. Do you have a job? ... You can't just be a deadbeat and enjoy this brotherhood. It ain't gonna happen."

The brotherhood and loyalty aspect of Mongols membership seems to be of ultimate importance to club members. One prospective member told Ling, "This is everything to me. This is my family. I'll sacrifice anything to be a full patch member." Ling called her experience "an interesting time" and "exhilarating" and even suggested that the club could serve a positive influence on "a lot of guys who ordinarily might do things they're not supposed to do."

Freedom loving bikers or sophisticated criminal enterprise?

According to another Hot Cars article, one of the most important rules of being a Mongol motorcycle club member is never backing down from a fight. The possible origin for this comes from the fact that the Mongols were founded by Hispanic bikers as an alternative to the Hells Angels motorcycle club, which was founded in 1948. In the late 1960s Hells Angels didn't allow non-white bikers to join as members. As a result, a rivalry arose between the two clubs, which resulted in the Mongols exerting force in order to establish a dominant presence in southern California.

The documentary "Hidden In America: Mongols Motorcycle Club" (available on YouTube) featured an interview with Stephen Stubbs, who serves as legal counsel to the club. Stubbs described Mongol ideals: "It goes to some core beliefs. The belief that the government should stay out of our lives. The belief that as long as they're not hurting anybody, they should be able to do what they please." Jorge Gil-Blanco, a retired intelligence officer from the San Jose Police Department who serves as an expert witness on the Mongols in court, opined, "You only see what they want you to see. [T]hey can be very nice individuals ... but as a whole they're involved in criminal activity, and it's important that people understand that."