What Happened To Boris Yeltsin?

Boris Yeltsin was an unlikely candidate to reach the pinnacle of the Russian political system. The man that would dissolve the USSR came from humble beginnings. According to History, he was born in the Russian village of Butka in the Ural Mountains to a family that had run afoul of Joseph Stalin's collectivist policies. Yeltsin was a wild child. Filled with the desire to fight on the front lines during the Second World War, according to Russia Beyond, a 10-year old Yeltsin broke into a Red Army depot and stole two grenades. While he and his friends were playing with them, he struck one with a hammer without removing the fuse and blew off two of his fingers. Ineligible to serve in the army, Yeltsin pursued an engineering degree and joined the Communist Party in 1961.

This was the first step of a political career that would plunge him into the heart of events during the USSR's turbulent final days in the 1990s and crystallize his reputation as the man that brought down the USSR. But he also became Russian president after the USSR collapsed, and this tenure is less well-known in the West, despite its implications for NATO-Russian relations and internal Russian politics today. Here is what happened to Yeltsin after the collapse of the USSR.

The disorders of 1989-91

According to History, Boris Yeltsin's political ascent in the late 1980s brought him into conflict with Soviet premier Mikhail Gorbachev. During these trying times for the USSR, Gorbachev hardly needed more trouble. As Rafael Reuveny and Aseem Prakash note, the disastrous Soviet invasion of Afghanistan had exposed the USSR's simmering ethnic tensions between Russians and non-Russians. The grievances of the Baltic Republics in particular resulted in a massive protest called the Baltic Way and demands for independence from Soviet rule.

Initially, Gorbachev did not respond to the protests. But when Lithuania declared independence in 1990, as Emerging Europe notes, he moved to crush Baltic separatism. The resulting standoff of January 13th, 1991 between Lithuanian protestors and Soviet tanks led to the deaths of 14 protestors and injured hundreds more. But the protestors held and Gorbachev's show of force failed. Despite a referendum that saw the majority of Soviet citizens (excluding Georgia, Armenia, Moldova, and the Baltic states) vote for the USSR's preservation (via Moscow Times), the hardline Soviet elements had lost faith in Gorbachev's ability to hold the state together. Thus, in 1991, a cadre of officers and officials attempted to overthrow the premier. Into this power vacuum stepped Boris Yeltsin.

Collapsing the USSR

Boris Yeltsin's fame in the West comes primarily from his role in the dissolution of the USSR. Now, as the BBC notes, the coup against Mikhail Gorbachev was not kindly met in Moscow, where Yeltsin served as president of the Russian SSR. Demonstrations erupted in front of the Russian parliament and the Red Army's tanks rolled in to disperse the protestors. But, they ended up joining and protecting the demonstrators instead and the coup fizzled out.

From atop one of the tanks, Yeltsin had what the BBC called "his finest hour." In his August 19th Address to the Russian People, he referred to the coup as "rightist, reactionary, and anti-constitutional," claiming that these elements wanted to return the USSR to its isolationist days during the height of the Cold War – against the will of its people. According to the New York Times, Yeltsin was opposed by every single constituent republic of the USSR except for three: Latvia, Estonia, and Lithuania. For their support, he recognized their independence and signed the USSR's death warrant.

Baltic independence spelled the end of the USSR. According to UPI, Yeltsin banned the Soviet Communist Party, proscribing his political enemies that had attempted the coup. On December 8th, 1991, Russia, Ukraine, and Belarus signed the Belavezha Accords dissolving the USSR by mutual consent. Boris Yeltsin thus wrote his place in the history books and became the first president of an independent Russia. Now came the less-glamorous and oft-forgotten part – actually governing.

The Harvard scandal

Boris Yeltsin's post-Soviet record as Russia's president is less stellar and unfamiliar to Western audiences today. Much of the negative press centered around his economic policies. According to The Nation, following the collapse of the USSR, Yeltsin's first priority was to liberalize the Russian economy on the advice of a cadre of Harvard affiliates led by Professor Jeffery Sachs.

Yeltsin appointed deputy PM Anatoly Chubais to oversee the reform. Leveraging connections with the Clinton Administration, Chubais and the Harvard Institute for International Development obtained billions in federal grants that presumably would go to Russia to restructure the economy. Some of the money was indeed used for the creation of new (and possibly superfluous) agencies. But the "Harvard boys," including Professor Andrei Schleifer also used the money for personal enrichment. According to the Institutional Investor, unscrupulous Russian government officials and members of the H.I.I.D funded no-show jobs, girlfriends and mistresses, and even their children's tennis lessons. Shleifer's wife Nancy Zimmerman started a private mutual fund in Russia, a violation that landed the couple in federal court.

The arrangement proved devastating for the Russian public, which suffered hyperinflation, shortages, and a collapse of their standard of living. Meanwhile, Harvard, Shleifer, et al. were forced to settle for $31 million in federal court after pleading guilty to misusing U.S. government funds. Harvard president Larry Summers testified in court in 2002 that the scandal irreparably damaged Russo-American trust, with consequences that continue to this day.

Rifts with NATO

Lately, the issue of expansion of NATO has been in the news as Russia and the bloc have come to blows over Ukraine's membership in the organization. Such tension, however, is nothing new. Although Boris Yeltsin was considered pro-Western, he fell out with NATO over its expansion towards Russia's historical sphere of influence. According to Professor Jim Goldgeier (via War on the Rocks), the Clinton administration promised Mikhail Gorbachev and Boris Yeltsin not to expand NATO east of Germany. Instead, the Partnership for Peace would bring together the old Warsaw Pact and post-Soviet states such as Russia and Ukraine into Europe to give them a seat at the bargaining table.

Now, Secretary of State Warren Christopher claimed that Yeltsin had misunderstood. According to the National Security Archive of George Washington University, NATO expansion had always been on the table. This strategy of "neo-containment," which confronted Russia with an alliance of potentially-hostile countries, united Yeltsin and his opponents against NATO and began the march towards the crisis seen today.

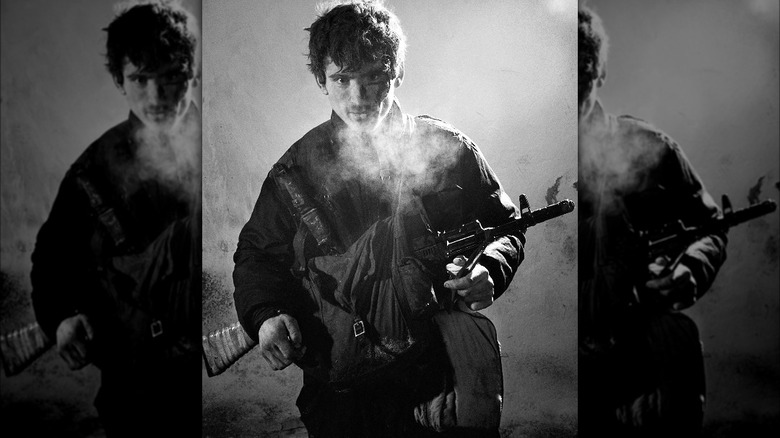

Russia's rift with NATO crystallized in 1999 over the Kosovo War. According to CNN, Yeltsin threatened to send Russian peacekeepers to support Belgrade and abort negotiations unless NATO ceased bombing Orthodox Serbs on behalf of Muslim Albanian separatists. Russia's parliament and people unanimously backed him in defense of a fellow Orthodox Christian state, resulting in protests outside Moscow's U.S. embassy (pictured above). Despite Yeltsin's tough words, however, Russia was in no shape for a new conflict following twin economic and military debacles that would define the Yeltsin presidency – the First Chechen War and the '98 economic meltdown.

The Chechen debacle

Russia and Chechnya have a long history of hostility. Given the wars of the 19th century to Stalin's mass deportation of Muslim Chechens from their homelands in WWII, it is little surprise that these fiercely-independent Caucasian mountaineers, per the National Interest, declared independence from the USSR in 1991 by defenestrating the local Communist Party head.

Boris Yeltsin decided to force the Chechen Republic of Ichkeria back into Russia in 1994, attacking the capital Grozny with three armored columns. However, this Russian army was not the Red Army of yesteryear. Its units were understrength, morale low, and many officers refused to send their men to fight Chechens, whom they perceived as fellow citizens. After a ferocious battle that leveled Grozny, the Chechen separatists fought back – and won.

The war cost Russia 8,000 men, shattered its army's prestige, and discredited Yeltsin in the public and international eye. The Russian state was completely humiliated, its army defeated by a ragtag group of militias in bloody urban warfare. Under the Khasavyurt Accords, Russia de facto recognized an independent Chechen Republic with costly implications for Russian security in the Caucasus. The International Spectator noted that Chechnya soon degenerated into a haven for Islamic extremism that spilled over into Russian territory. Once Islamist militants under Shamil Basayev and Saudi Afghanistan mujahid Ibn al-Khattab attacked Russian territory in 1999, Yeltsin saw an opportunity to bring Chechnya back into Russian orbit. But his days as president were numbered as an economic collapse brought Russia to its knees and ushered in new leadership.

The '98 Crisis brings him down

Despite the Chechen debacle, good news appeared on the economic front. According to the Moscow Times, 1996-97 saw the Russian economy stabilize as inflation, which had at one point hit 2,500% (via The Nation), fell into the teens. The Russian ruble, meanwhile, stabilized at a 6:1 exchange rate against the dollar and there was optimism on the Russian stock market, which enjoyed a boom year. One investment banker interviewed claimed that he did not know any colleague that was "not worth $3 million."

As it turned out, the recovery was a mirage. According to Rabobank, on August 13, 1998, the Russian stock market collapsed on rumors of currency devaluation and debt defaults. In fact, four days later, that is exactly what happened. The ruble, which until then, had maintained its value on the back of higher oil prices, crashed in value over the following weeks as oil prices slumped to a low of $10/barrel. Russia was now losing money, requiring prices of $14 at least to maintain an even balance. The consequences for ordinary Russians, once again, were not good. Standards of living plunged to the point that some Russians were living on less than $2 per day. According to the left-leaning Jacobin Magazine, Boris Yeltsin reshuffled his cabinet amid the fallout and made the most important appointment of his tenure, nominating the FSB head and political unknown named Vladimir Putin to the post of prime minister. Yeltsin's sinking popularity amid scandals and economic problems soon opened a power vacuum that the new face soon filled.

Changing of the guard

By 1999, Boris Yeltsin was in trouble. A new conflict in Chechnya in 1999 and the 1998 economic crisis had damaged his reputation among the Russian public. Now, fresh scandals came to light that implicated him personally. The most famous (although by no means the only one) was the Mabetex scandal. According to STRATFOR (via Asia Times), the Swiss construction firm Mabetex, led by Kosovar tycoon Behgjet Pacolli (above), issued Yeltsin and his two daughters credit cards linked to a $1 million Hungarian bank account, an enormous sum in an economically-devastated Russia. According to the Chicago Tribune, this and more, including private yachts, was all a bribe to secure a construction contract for the Kremlin's renovation.

The scandal itself was not the main problem. Corruption in post-Soviet Russia was the norm. But Yeltsin's involvement was another story. It confirmed to the Russian public that their government, allegedly a democratic entity representing the public interest, was nothing more than a giant kleptocracy. With nearly 800 officials implicated, it is easy to see why this line of thinking prevailed. Thus, on New Year's Eve of 1999, facing a trust rating of 4%, Yeltsin resigned, appointing Vladimir Putin, who was not implicated in the scandal, as interim president.

Immunity

Boris Yeltsin's resignation was a calculated move, and the disgraced president, before leaving office, had ensured that his exit would be as smooth for him as possible. As STRATFOR noted (via Asia Times), Yeltsin probably had three options as the walls closed around him. He could flee the country, declare a state of emergency (aka martial law), or resign and leave the presidency to an ally – or at least someone willing to overlook his alleged crimes.

Yeltsin chose the latter option, as noted earlier, leaving Vladimir Putin (above with Yeltsin's wife) the Russian presidency. But this came as part of a larger deal. According to the Irish Times, Putin in return granted Yeltsin life-long blanket immunity from prosecution. In fact, the decree also absolved him from any "bodily search and interrogation" too. Since the protections applied to his "place of residence, his offices ... his vehicles, his means of communication, his baggage and his correspondence," it is likely that his wife and daughters, who were all ensnared in the Mabetex Scandal, could all sleep soundly as long as they remained close to Yeltsin, preferably at the same address. Thus, the Irish Times notes that Yeltsin became a sort of Russian Richard Nixon, obtaining a get-out-of-jail-free card in return for ensuring his successor's position.

A divided legacy

Because of his mixed record, Boris Yeltsin is simultaneously revered and reviled. Former Brookings president Strobe Talbott (via PBS) portrayed Yeltsin as a courageous, optimistic reformer and fighter. His achievements in bringing down the USSR and ensuring an "orderly transition" to a democratic Russia, Talbott argues, cannot be underplayed. But when asked how Russia had improved, Talbott could only name Russian democracy.

Yeltsin's former finance minister Boris Fyodorov provided a more nuanced critique. Fyodorov called Yeltsin "a political fighter" with little understanding of economics. Thus he delegated such matters to people such as Fyodorov, who presumably, were experts. Despite his shortcomings, Fyodorov argued, Yeltsin's Russia had witnessed the growth of private property, business, and even car ownership. Most importantly, he had offered an alternative to communism, despite complaints among Russia's economically disenfranchised (especially pensioners that lost everything) that the old communist model was more stable.

Despite these positive developments, it is impossible to ignore Yeltsin's poor overall record. Although seen as an enemy of totalitarianism, DW notes that he ordered the Russian army to shell parliament during the 1993 Constitutional Crisis (above) to ram through a new constitution that expanded presidential powers beyond their intended scope, allowing Vladimir Putin to consolidate power later on. Meanwhile, according to NPR, deaths from despair, drug abuse (via PBS), and, for the elderly, neglect skyrocketed and life expectancy slid a whopping four years. In short, Yeltsin was a "magnificent rebel," but not a "constructive leader."

The anthem controversy

Following his resignation, Boris Yeltsin kept a low profile, only speaking out on two occasions that the Western media recorded. The first was in 2000, approximately one year after his resignation. According to the BBC, when the USSR collapsed in 1991, a newly-independent Russia chose Mikhail Glinka's 19th-century "Patriotic Song" as the country's national anthem. It was unpopular, as it did not inspire any patriotic feeling and had no lyrics. It replaced the popular WWII-era Soviet Anthem, which glorified Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin and his predecessors.

Under Vladimir Putin, the old Soviet Anthem enjoyed a resurgence in popularity for its "stirring, singable melody" and its associations with the Soviet victory against Germany in WWII. Thus, the Russian government restored the old Soviet tune with Law 3-FKZ but adopted new lyrics that scrubbed all mentions of past communist leaders.

Yeltsin publicly criticized his old subordinate for caving in to popular demand. He viewed the old anthem as a relic of the old Soviet system that had no place in a democratic Russia. Putin responded that all Russians, including Mr. Yeltsin, were entitled to their opinions and should be respected. In the end, Yeltsin's criticism was drowned out amid public support for the new anthem. The current Russian National Anthem was rolled out two weeks later.

Boris Yeltsin and Russia's War on Terror

In 2004, Vladimir Putin signed one of Russia's more controversial pieces of legislation. According to Radio Free Europe, the bill allowed Moscow to appoint regional governors and dissolve local legislatures that rejected proposed candidates. Russia's Constitutional Court did not strike down the measure, and it went through.

Putin's opponents were not pleased, calling it an attempt to "[return] Russia to the Soviet era," when Moscow's party bosses made key gubernatorial opponents irrespective of public opinion. Boris Yeltsin was among those critics, saving his most vociferous objections for private conversations. According to RFERL, the former president criticized Putin for infringing on Russian federalism, which envisioned a government that delegated sovereignty to local authorities independent of the Kremlin.

So how was it justified? The bill must be contextualized in light of the Beslan School Siege and the politico-religious conflicts in the North Caucasus. As Britannica notes, in 2004, Chechen and Ingush Islamists seized a school in Christian-majority North Ossetia-Alania, leaving 330 people (mostly children) dead. The governors' bill was sold as a counterterrorism measure in response to Beslan that gave Putin an iron grip over the governments of the Muslim-majority North Caucasus. The main beneficiaries were Putin loyalists such as Chechen President Ramzan Kadyrov (via BBC), who has faithfully curtailed Islamic militancy in Chechnya. But there is little doubt that it has increased Putin's power throughout the rest of Russia even where terrorism is not a problem, leading doubters – such as Yeltsin – to question its necessity.

Death and historic first

Boris Yeltsin was a sick man during the last two decades of his life, suffering from heart problems and alcohol abuse, which took a toll on his health and led to his eventual death in 2007. His alcoholism was well known, but the extent to which it affected him did not come out until 2009. According to the Clinton Tapes (via History), it turned out that during a state visit in 1996, an intoxicated Yeltsin had left his lodging for a nighttime stroll down Pennsylvania Avenue – in his underwear. When the Secret Service found him, he demanded a taxi so that he could go buy pizza. As funny as the incident was, it was a sign of a major problem. At the end of his tenure, Yeltsin was frequently drunk on the job. Simply put, he had become a public embarrassment. Thus, it is almost surprising that he lived to be 76.

When Boris Yeltsin died, he received a state funeral, which would prove to be a historic first in the newly-independent Russia. According to Time, he became the first Russian head of state since Czar Alexander III in 1894 to receive an Orthodox funeral at Moscow's Cathedral of Christ the Savior. Thus Russia's controversial first president passed away, his funeral a symbol of a system that mixed the old pre-communist ways with the new, democratic modern world.