The Hells Canyon Massacre Explained

During the 19th century, there was a rise in the number of people emigrating from China to various countries around the world. It's estimated that up to 2.5 million people left China, many from the Guangdong province, fleeing both "intense conflicts," like the Opium Wars and the Red Turban Rebellion, as well as "harsh economic conditions." And as stories began to circulate of those who'd gone to America and came back with an abundance of wealth, whether through gold mining or employment, some Chinese people decided to set out across the Pacific to find their fortune.

The discovery of gold in California led many Chinese immigrants into the gold mining industry. Some people in the Guangdong Province in China called "the faraway land" where gold nuggets could be found on the street Gum Shan, or Gold Mountain, But as the Library of Congress notes, those who made it to the United States found that Gum Shan "was an illusion. Mining was uncertain work, and the goldfields were littered with disappointed prospectors and hostile locals."

Often, this hostility quickly turned violent and dozens of Chinese gold miners lost their lives at the hands of Americans who didn't enjoy the competition, were racist against Chinese people, or both. These attitudes were present even before the implementation of the Chinese Exclusion Act and they only got worse after the act was passed. This is the Hells Canyon Massacre explained.

Chinese laborers in America

During the 19th century, Chinese people who immigrated to the United States were turned into an essential part of the labor force. Immigrating to both the mainland United States as well as the Kingdom of Hawai'i, Chinese workers were soon channeled by white employers into specific industries, such building the Transcontinental Railroad or working on sugar plantations.

Although Hawai'i wasn't annexed by the United States until 1893, the Western sugar industry obtained a majority of the best cane land after The Great Mahele, which "institutionalized the private ownership or leasing of land tracts" in 1848, according to the University of Hawai'i. Throughout the second half of the 1800s, up to 46,000 Chinese people immigrated to Hawai'i and worked on the sugar plantations. Hundreds of thousands of other people were also brought to Hawai'i by the sugar growers, including people from Japan, the Philippines, Portugal, and Puerto Rico, who were "used generally to offset the bargaining power of its predecessor."

Meanwhile, on the mainland United States, up to 15,000 Chinese people worked on the transcontinental railroad between 1863 and 1869. The Guardian reports that not only were they paid less than white workers, but white workers were given "accommodation in train cars" while Chinese workers were forced to live in tents during the building of the railroad.

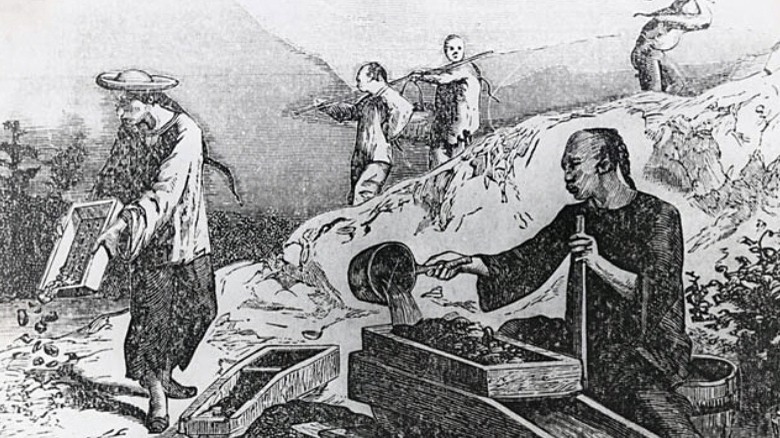

Gold mining

It's estimated that over 100,000 Chinese people, mostly men, came to the United States during the second half of the 19th century for the Gold Rush. Many who immigrated were young married men who came as contract laborers or free laborers "under the credit ticket system." Some who immigrated to the United States ended up working in the gold mining industry. Mae Ngai writes in "The Chinese Question" that by the end of the 1850s, Chinese miners represented up to 25% of the population in California mining districts, despite being only 6% of the state's population.

However, according to "Glass Ceilings and Asian Americans" by Deborah Woo, mining had its dangers, some of which weren't even associated with the act of mining. "Chinese who competed with white miners in the more productive or lucrative mining sites were beaten, shot, and otherwise forcibly removed, their campsites burned." By 1862, there were at least 88 known murders of Chinese people in California. And justice was rare, since the testimony of a Chinese person was considered inadmissible, per the ruling of People v. Hall (1854).

In 1850, anti-immigrant sentiment in California led to the Foreign Miners License Law, which charged all non-U.S. citizens $20 per month and targeted Latin American miners as well as Chinese miners. Many left the mining industry due to the tax and although the amount was reduced in 1885, the Foreign Miners License Law remained until 1870, according to "Asian American Society."

The Chinese Exclusion Act

The first Chinese exclusion act was technically passed in 1875. Known as the Page Law, on paper the law was an anti-sex trafficking and anti-prostitution law that sought to prohibit "any importation of, women into the United States for the purposes of prostitution" as well as prohibiting women from "any Oriental country" to enter the United States "for lewd and immoral purposes." However, as Takaki notes in "Strangers From Another World," this law was enforced "so strictly and broadly" that almost every Chinese woman was excluded.

Chinese women who tried to immigrate to the United States were subjected to "rigorous interrogation and cross-examination" and between 1876 and 1882, the number of Chinese women entering the United States fell by 68%. A few months before the Chinese Exclusion Act started being enforced, over 39,000 Chinese people were able to enter the United States. "But this massive migration included only 136 women."

The Chinese Exclusion Act was signed into law by President Chester A. Arthur on May 6, 1882. According to the Equal Justice Initiative, "banned all immigrants from China for 10 years, prohibited Chinese immigrants from becoming American citizens, and restricted the entry and re-entry of Chinese nationals." The act was subsequently extended twice and in 1902, it was made permanent. The act wouldn't be lifted until the Immigration Act of 1965. After the passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act, The New Yorker writes that "efforts to drive out the Chinese intensified."

The Tacoma Method

Although the violence against Chinese people escalated after the passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act, there were numerous riots and massacres fueled by sinophobia over a decade before the act's passage. One notable example includes the 1871 Chinese massacre in Los Angeles, which left at least 20 Chinese people dead, some of them as young as 14, and is considered to be "one of the worst instances of a mass lynching" in American history.

According to The New Yorker, a "model for ridding communities" of Chinese people was known across the West Coast as the Tacoma Method, named after an 1885 riot in Tacoma, Washington. White people in the city of Tacoma reportedly set a deadline and told several hundred Chinese residents that they had until November 1 to leave the city. After the deadline passed, a group of white vigilantes with pistols and clubs hunted down the remaining Chinese residents on November 3 and "herded about two hundred Chinese on a muddy march to the train station." Those who couldn't afford train fare were forced to jump onto a freight train or walk for days along the tracks.

The Tacoma Method writes that although 27 white men were indicted for the expulsion of Chinese residents from Tacoma, none of them were convicted, and "in many ways, the city thought of them as heroes."

Heading down Snake River

In the autumn of 1886, two groups of Chinese gold miners employed by the Sam Yup Company, also known as the Sanyi District Association, of San Francisco set sail down the Snake River in the Idaho Territory near the border of Oregon, with one group led by Chea Po and the other led by Lee She. According to "Massacred For Gold" by R. Gregory Nokes, the two groups were headed to Hells Canyon in Oregon, known at the time as Snake River Canyon. The journey would have taken several weeks if not more, depending on how often they stopped to mine for gold.

Although Chea Po eventually made a camp at Deep Creek, Lee She ended up mining at Salt Creek, 20 miles upstream and "at what would prove to be a safe distance from the attack." Chea's group of miners reportedly found "a rich deposit of nuggets and heavy gold flakes along the riverbank" and ended up staying and mining the cove for 8 months.

Unfortunately, there's little information available about the miners and there's also a lack of reliable information about the details of the massacre as well. According to History Cooperative, this is partly due to "a failure by law enforcement agencies to fully investigate the crime and partly because key documents from the investigation were missing, including all records of the 1888 trial."

The Hells Canyon Massacre

Although it's not clear exactly when the Chinese gold miners led by Chea were ambushed, it's believed that sometime around May 1887, they were attacked by a group of seven white horse thieves; Bruce "Blue" Evans, J. Titus "Tighty" Canfield, Frank Vaughn, Robert McMillan, Hezekiah "Carl" Hughes, Hiram Maynard, and Homer "Omar" LaRue. The group of horse thieves was led by 31-year-old Evans, and History Cooperative writes that the oldest was Maynard, at 38, while McMillan was the youngest of the group at 15 years old.

The Oregon History Project writes that Chea's group of miners were reportedly ambushed by Evans' men and shot as they tried to run away. After the massacre, the bodies were subsequently "mutilated in a most shocking manner" and thrown into the river. But according to the "History of Asian Americans" by Jonathan H. X. Lee, this was just the beginning of a brief killing spree.

10 Chinese people were killed during the first massacre and after eight other Chinese miners stumbled upon the site, they were subsequently murdered as well. Evans and his men then reportedly traveled to another camp of Chinese miners and killed 13 more people. Over the course of two days, it's believed that at least 31 Chinese people were slaughtered. This 2-day slaughter became known as the Hells Canyon Massacre or the Snake River Massacre.

Finding the bodies

Only the names of 10 of the victims of the massacres are known: Chea Po, Chea Sun, Chea-Yow, Chea-Shun, Chea Cheong, Chea Ling, Chea Chow, Chea Lin Chung, Kong Mun Kow, and Kong Ngan, per the Office of the Historian.

Roughly a month after the massacres, Lee See's group stumbled across the murder sit and immediately fled back to Lewiston, Idaho to report the incident. According to "In Pursuit of Gold" by Sue Fawn Chung, the sheriff in Lewiston, Idaho said that since the murders happened in Oregon, he had no jurisdiction. "Meanwhile, the sheriff in Oregon claimed the murderers were in Idaho and he had no authority to pursue them especially since Idaho was still a territory."

Although the Chinese Consul-General in San Francisco and the Sam Yup Company put together a $1,000 reward for the identity of the murderers and hired Joseph K. Vincent to find the murderers but to little avail.

How much was stolen?

Estimates for exactly how much gold was stolen from the massacred Chinese gold miners vary. According to an article published in the Oregon Scout in 1888, all of the money and gold dust amounted to "between $4,000 and $5,000," or between $122,000 and $152,500 today. Meanwhile, the New York Times writes that the gold was worth as much as $50,000, or $1.5 million today. The gold dust was reportedly given to J. Titus "Tighty" Canfield who was supposed to sell it for them, but Canfield reportedly "skipped the country, and the rest of the parties got nothing."

History Cooperative writes that Chang Yen Hoon, the minister in charge of China's legation in Washington, D.C., even notified Secretary of State Thomas F. Bayard of the massacre in February 1888. However, Bayard reportedly replied that Chang's letter was "confusing and even contradictory."

In March 1888, Chang also submitted a claim seeking compensation for crimes against Chinese people in the state of California as well as several territories. "The claim was for $346,619.75, of which $100,000 would be indemnification for forty deaths — or $2,500 per death." However, the claim didn't include the Hells Canyon massacre, since "no accurate information is yet received." The United States ended up approving a compensation package of $276,619.75, although it's disputed whether or not the compensation was actually paid.

Frank Vaughn's confession

Although it's not clear exactly when it happened, at some point Frank Vaughn turned on the other members of the group. But as History Cooperative notes, it's also not clear if "Vaughn stepped forward on his own or after being confronted." After Vaughn's testimony, the other six members of the gang were indicted. The Oregon State Bar Bulletin writes that in exchange for his grand jury testimony, Vaughn was given immunity.

Not all of the members of the gang ended up being arrested for the massacre. According to The Oregon History Project, Evans was arrested briefly for stealing livestock but managed to escape and flee. LaRue left the region after the massacre and is rumored to have been killed during a gambling dispute. Some reports also claim that Canfield was reportedly arrested at one point and it's believed that he eventually ended up in Idaho as a blacksmith.

A short trial

The murder trial for the massacre of the Chinese gold miners lasted three days and was held in August 1888 in Enterprise, Oregon. During the trial against Maynard, McMillan, and Hughes, Vaughn reportedly changed his story. Although in the grand jury indictment he claimed that the other six men were "acting together," during his deposition Vaughn "shifted all the blame to Evans, Canfield, and LaRue."

The trial lasted from August 30 to September 1 and Maynard, McMillan and Hughes were all found not guilty by the all-white jury. George Craig, a rancher who attended the trial, stated that "I guess if they had killed 31 white men, something would have been done about it, but none of the jury knew the Chinamen or cared much about it, so they turned the men loose," per History Cooperative. And during the trial, nobody asked the men about what happened to all the gold that they'd stolen.

According to In Pursuit of Gold, after the trial "all of the court documents mysteriously disappeared only to be found in 1995," over 100 years later.

Robert McMillan's deathbed confession

McMillan was only 18 years when he died from rheumatic fever two years after the trial in 1890. But according to Histories of the Early West, it was on his deathbed that he made a confession to his father, Hugh McMillan. In 1891, Hugh shared his son's deathbed confession in The Statesman, a Walla Walla newspaper, and, revealing that "My son and Evans, Canfield, Larue, and Vaughan went to the Chinese camp on the Snake River. There were 13 Chinese in the camp and they were fired on. Twelve Chinese were instantly killed and one other caught afterwards and his brains beaten out."

McMillan's deathbed confession also confirmed the murders of the 21 other Chinese people the following day, although Hugh wrote that "My son was present only the first day, but was acquainted with the facts as they were talked over by the parties in his presence." McMillan also claimed that he'd gotten away with up to $50,000 in gold, but it's unclear if this was an exaggeration.

According to an 1892 issue of The Friend, McMillan's confession was reportedly translated into Chinese and "with a full account of the whole terrible affair, has been sent to the authorities at Peking, with a request for instructions." However, it's unclear whether this message ever reached Peking or if "instructions" were ever given.

Legacy of the massacre

The story of the massacre was brought back to public attention in 1995, when court documents relating to the murder trial were discovered by author R. Gregory Nokes in a courtroom safe in Wallowa County. And according to judge Ben Boswell of the Wallowa County Court, the hidden nature of these documents wasn't accidental. "The records were more than just lost. They seem to have been hidden. Somebody intentionally tried to keep this story from happening. Someone intentionally caused people to forget," per The Lewiston Tribune.

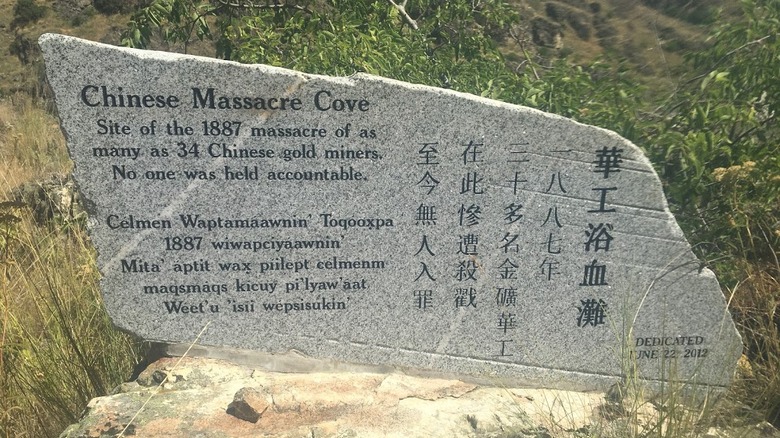

East Oregonian reports that in 2005, Snake River cove, where the massacre occurred, was renamed Chinese Massacre Cove. And on June 22, 2012, a granite memorial was also installed at the cove and dedicated to the victims of the massacre. The memorial reads "Site of the 1887 massacre of as many as 34 Chinese gold miners. No one was held accountable," written in English, Chinese, and Nez Perce.