The Tragic History Of Ukraine's Babyn Yar

The Babyn Yar massacre is considered one of the largest massacres that was committed during the Holocaust. Targeting Jewish people in Soviet Ukraine as well as Roma people, disabled people, and Soviet POWs, Babyn Yar went from being a ravine named after old women to a mass grave site littered with violence.

It took years for the site of the massacre to be recognized, and by that point, the bodies of the victims had already been buried, exhumed, burned, mudslided, and covered up to create a road. And then 80 years after the massacre, Babyn Yar found itself to be once again the site of warfare as Russian President Vladimir Putin launched an attack on Ukraine.

But what exactly happened during the massacre and why is it not as well known as some of the other atrocities that occurred during the Holocaust? This is the tragic history of Ukraine's Babyn Yar.

The fight for Kyiv

On August 7, 1941, the Nazi German Army moved to take the city of Kyiv in Soviet Ukraine as part of Operation Barbarossa. Within a month, the German Army managed to successfully encircle the city, surrounding the Soviet Red Army in Kyiv. War History Online describes this as the "largest encirclement in the history of warfare."

The battle for the city came to be known as the First Battle of Kyiv, not to be confused with the Second Battle of Kyiv that occurred two years later in 1943. And after about a month of fighting and hundreds of thousands of deaths, the Germans took the citadel on September 19 and victory was declared as over half a million Soviet soldiers surrendered. It's estimated that over 600,000 Soviet soldiers and 62,000 German soldiers were killed. The number of civilian casualties is unknown.

After their victory over Kyiv, they "calculated that they had taken 665,000 prisoners [captured Red Army soldiers] along with staggering quantities of tanks, guns, and equipment." According to "Between Hitler and Stalin," the majority of those captured were "starved to death or died of exposure in open-air concentration stockades in the winter of 1941-42." The New Republic reports that in 1941, the population of Kyiv was around 815,000 people, but by the time the First Battle of Kyiv was occurring, up to half of the city "had already fled the advancing German armies."

NKVD bombs

The day after German forces occupied Kyiv, a mine exploded near the Caves Monastery. Karel C. Berkhoff writes in Babi Yar that all the Germans who were quartered there were killed and almost immediately, German officers started collecting Jewish pedestrians. "Germans checked people's identity papers, and now the Soviet entry on 'nationality' became a great liability."

Four days later, several bombs went off around Kyiv, "all evening and night, and also the next day, with intervals of just minutes, explosions continued." These bombs had been placed there by NKVD officers, the Soviet precursor to the KBG, as well as Red Army engineers. After the explosions, Soviet agents also threw bottles of fuel to cause the fires to spread. The fires burned for more than a week and in total, 200 Germans soldiers were killed.

Rumors quickly spread that blamed the Jewish people for the explosions and the fires. Hundreds of Jewish people as well as "NKVD agents, political officers, and partisans" were arrested and murdered. Although an Operations Situation Report Einsatzgruppe C report from 1941 blames Jewish people for participating in the arson, the Brandeis Graduate Journal writes that "SS detachments that had already executed the Jews in other places arrived in Kyiv on September 21-25," implying that the plan for execution was already in motion.

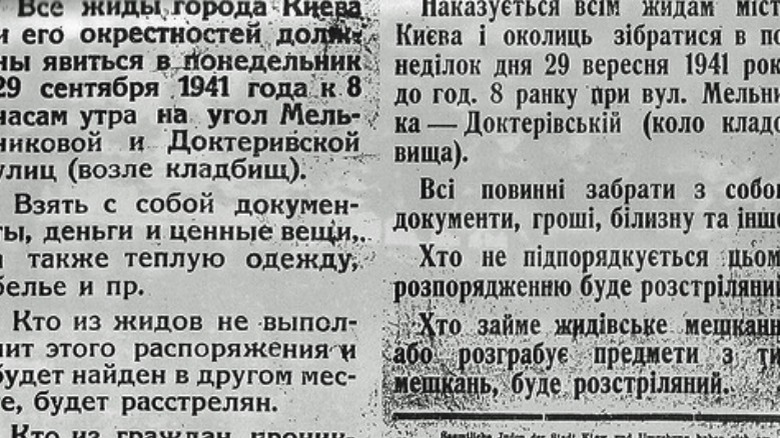

Ordered to appear

On Sunday, September 28, 1941, Ukrainian police posted a notice around Kyiv addressing the Jewish people of the city, written in Ukrainian, Russian, and German. In "Babi Yar," Anatoly Kuznetsov reproduces the notice, which stated that all Jewish people in Kyiv are to report to an intersection near the cemetery the following day, September 29, bringing all their "documents, money, valuables, as well as warm clothes, underwear, etc." The notice also stated that any Jewish person "not carrying out this instruction and who is found elsewhere will be shot."

According to Berkhoff's Babi Yar, the order wasn't signed, and "no one involved in composing its text knew much about Kyiv, for the order claimed that the intersection was 'near the cemeteries,' which was incorrect."

Based on this notice, the majority of Jewish people believed that they were to be resettled, especially because the Lukianivka railway station was near the intersection where they were supposed to congregate, writes the Brandeis Graduate Journal. This belief was also based on the rumors of resettlement that were spread by non-Jewish Ukrainian residents.

Point of no return

On September 29, thousands of Jewish people of all ages as well as their "non-Jewish spouses, other relatives, and friends" arrived at the intersection. As they walked to the location with all of their precious belongings, "some onlookers watched and sighed, [while] others jeered and shouted insults." But instead of being shuttled into the railway cars, they were divided into groups and moved towards Babyn Yar, which translates to Old Women's Ravine. There, German soldiers confiscated everyone's documents and "burned them before their very eyes."

Berkhoff writes in Babi Yar that after being forced to undress, everyone was made to enter the ravine and people who refused were beaten and shot on the spot. Many were chased into the ravine "through a vicious gauntlet of Germans with rubber clubs, big sticks, and dogs." Those who had gone directly to the Lukianivka station were also rounded up by the Ukrainian police and German SS.

Holocaust and Genocide Studies writes that extra alcohol rations were given for participating in the massacre and a banquet was even sponsored afterwards for the killers. By the evening, the soldiers took a break from the mass shooting, and "Germans assisted by non-Germans walked across the bodies of the victims" looking for survivors to execute. People who continued to arrive at the gathering place were "locked up in the garages nearby" until the shootings resumed in the morning.

Layers of bodies

The massacres continued on September 30 and at the end of the second day, those who were still alive in the ravine were executed. And the Jewish residents of Ukraine weren't the only ones targeted during this massacre. According to Babi Yar and the Nazi Genocide of Roma by Andrej Kotljarchuk, Roma people were also killed at Babi Yar in September 1941. Otto Ohlendorf, commander of Einsatzgruppe D, testified at his trial that "he saw no difference between Jews and Roma, whom he considered dire threats to Wehrmacht security in Russia," per "The Holocaust" by David M. Crowe.

The Mass Violence and Resistance – Research Network writes that people were forced to lie down among the bodies, which were also covered with a layer of "chloride of lime, sand, and soil." In Babi Yar, Berkhoff writes "Babies were ripped from parents' arms and simply thrown into the ravine." Before long, the bodies piled on top of one another. According to "Collaboration in the Holocaust" by Martin Dean, the local Ukrainian auxiliary police, known as the Hilfspolizei in German, collaborated with the Nazis and participated in the massacres. And Brandeis Graduate Journal also writes that some non-Jewish people "denounced hidden Jews to Nazis in the anticipation of a reward."

Jewish and Roma people continued to be murdered in Kyiv throughout the beginning of October. Those who were killed were largely disabled people as well as those who'd managed to hide or escape the first wave of killings.

Eliminating the evidence

Two years later, during the summer of 1943, hundreds of surviving people imprisoned at the Syrets concentration camp were forced to destroy all the evidence of the massacre. "To achieve this the corpses were exhumed and burnt," according to Brandeis Graduate Journal. The Mass Violence and Resistance – Research Network writes that this endeavor was known as Operation 1005 and "was given top priority after the discovery of mass graves by the Soviet Union in the Russian city of Rostov."

In 1947, SS Colonel Paul Blobel testified that after exhuming the mass grave, "the corpses were covered with inflammable materials and set on fire. About two days passed before the fire had burned down to the bottom of the trench." Berkhoff writes in Babi Yar that it's estimated over "100,000 bodies were incinerated."

Freshly killed people were also reportedly brought to the fires to be burned, some of whom had been gassed in German vans. However, it's unclear whether or not these villagers were also Jewish.

How many were killed?

It's estimated that between 33,000 and 100,000 Jewish people in Kyiv were murdered during the Babyn Yar massacre. Those who were forced to exhume and burn the bodies would later testify that "a total of 150,000-180,000 corpses of Babi Yar victims were cremated." And the Soviet Extraordinary State Commission report on Kyiv also referred to "over 100,000 men, women, and children and old people in Babi Yar," according to the Mass Violence and Resistance – Research Network.

The estimate of 33,000 people comes from a Nazi report, but cannot be assumed to be entirely accurate because "there is no evidence that the Nazis registered [all of] their victims or kept an exact count."

It's unclear exactly how many Roma people were murdered during Babyn Yar, but it's estimated that between 26,000 to 63,000 Roma people were killed in Ukraine in total during the WWII genocide, "with the likely figure to be in excess of about 40,000," according to "Disputed Memory," edited by Barbara Törnquist Plewa and Tea Sindbæk Andersen. Unfortunately, accurate figures are hard to come by because report published by the Extraordinary Commission for Investigation of War Crimes, the Roma weren't specified because they were counted as "murdered civil citizens," writes Baltic Worlds.

The survivors

Despite the violence that swept across Kyiv, some Jewish people managed to survive the massacres. Dina Pronicheva, a Jewish actress in Soviet Ukraine, survived the initial shooting in the ravine by jumping into the ravine before she was hit. When the mass shooting ceased in the evening, "her killers became suspicious and trampled her, to verify that she was dead," according to Babi Yar by Berkhoff.

But despite the beating, Pronicheva would later testify that she didn't make a single sound and after they decided that she was dead, they left her and began shoveling dirt onto the corpses. She managed to crawl out from under the sand and away from the mass grave, although

The Washington Post reports that Raisa Dashkovskaia also managed to survive the first day of the massacre while her parents, her sisters, and her son were murdered. "She crawled from under the dead bodies and took refuge with Ukrainian friends." Several others, like Raya Dashkevich, had similar experiences of somehow regaining consciousness in the ravine and managing to briefly crawl away from the devastation.

The Nuremberg Trial

After the International Military Tribunal at Nuremberg concluded, there were twelve further trials known as the Subsequent Nuremberg Trials. These trials were "for the purpose of determining the guilt of second-tier Nazis" accused of war crimes and crimes against humanity, according to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

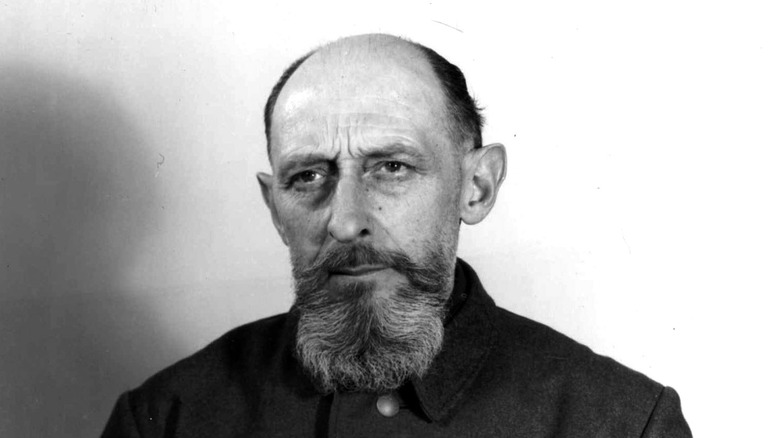

SS Standartenführer Paul Blobel, who was involved in both the massacre and the destruction of the evidence, was one of the defendants at the Einsatzgruppen Trial, the ninth of the twelve Subsequent Nuremberg Trials. His superior Einsatzgruppe C leader Otto Rasch was also charged but Rasch died in custody before the trials. Meanwhile, Blobel was sentenced to death and hanged in June 1951.

The Babyn Yar Memory Place writes that during the 1960s, there was also an investigation by the Attorney General's Office in Frankfurt am Main, which ended up charging 10 people, nine of whom were involved in the Babyn Yar massacre. The trial was held in 1967 and out of the nine charged, five were given prison sentences.

Soviet memory

Initially, Soviet authorities were relatively open about what happened at Babyn Yar after the liberation of Kyiv. But even these early government reports regarded the massacre as being against Soviet citizens in general, rather than "against the Jewish community specifically." But after the Second World War ended, Brandeis Graduate Journal writes that Soviet authorities "changed their attitude" and made an effort to "eliminate all references to Babi Yar." This policy remained in place even after Stalin's death in 1953.

According to "Holocaust Resistance in Europe and America," edited by Victoria Khiterer and Abigail S. Gruber, Babyn Yar was filled with "liquid mud waste from nearby brick factories" and built a dam to hold back the mud in the 1950s. There were even plans to turn the ravine into a sports station or an amusement park.

In 1961, Yevgeny Yevtushenko wrote a poem that began with the line "No monument stands over Babi Yar." Not only was the poem an indictment of Soviet suppression of the massacre, but it also connected the massacre to antisemitism both inside and outside the Soviet Union. The Soviet Union wouldn't build a memorial for the massacre until 1976 "in response to worldwide criticism," according to "The Holocaust in the Soviet Union" by Lucjan Dobroszycki and Jeffrey S. Gurock. But even then, the inscription on the monument read "To the Soviet citizens – the victims of fascism" without any mention of the Jewish, Roma, and disabled people who made up a majority of the victims.

Kurenivka mudslide

On March 13, 1961, the dam holding back all of the mud dumped into Babyn Yar broke, causing a massive mudslide. The wave of mud that resulted was over 13 feet tall, a mixture of mud and human remains, and it destroyed everything in its path. "It flooded part of the Kurenivka district" and although government figures claimed that only 145 people were killed 143 were injured, it's believed that up to 1,500 people may have died due to the mudslide.

"Holocaust Resistance in Europe and America" writes that "many people saw the mud flood as divine retribution for the attempt to erase the traces of the Babi Yar massacre." However, divine retribution wasn't enough. Berkhoff writes in Babi Yar that after the ravine was refilled, the new Novo-Okruzhna Street was partly built on top of Babyn Yar in 1969 and by the late 1970s, the rest of the area was turned into a Park of Culture and Recreation.

"Foreign tourists sometimes asked to be taken to Babi Yar" but Soviet tourist agency guides would refuse, saying that it was "far away, and uninteresting."

Memorials

After Ukraine declared its independence from the Soviet Union in 1991, that year the Ukrainian government commemorated the 50th anniversary of Babyn Yar. For the first time, Ukrainian President Leonid Kravchuk stated at the memorial ceremony at the gravesite that "Today, at this solemn event, it is natural for us to beg forgiveness from the Jewish people," also stating that "part of the blame is on us," reports The Washington Post.

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, several new memorials were placed at Babyn Yar, commemorating Jewish people as well as Roma people, writes The Conversation, although none of these memorials were state-sponsored.

The first state-sponsored memorial project for Babyn Yar was created in 2017 during the presidency of Petro Poroshenko, writes the Centre for Eastern Studies, although the project was never implemented. Meanwhile, in 2016, the Babi Yar Holocaust Memorial Center was established by Russian billionaires Mikhail Fridman and German Khan. "Although Fridman and Chan are not among Putin's close collaborators, they are linked with the Russian leadership by a number of political and business initiatives. This triggers the risk of Russia's interference in the memorial's project, and at the same time – in the sensitive realm of Ukraine's politics of memory."

Putin bombs Kyiv

On March 1, 2022, during the Russian invasion of Ukraine, Russian forces fired at the Kyiv television tower which is located next to the Babyn Yar memorial. During this attack, five people were killed, Al Jazeera writes, and there were reports that the new Babyn Yar memorial built in 2021 was also damaged during the attack. Newsweek also reports that surrounding Jewish graves were also damaged, as was a museum building that "was not yet in use." However, the full extent of the damage remains unclear as of March 4, 2022.

According to The Conversation, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy responded to the bombing by stating "what is the point of saying 'never again' for 80 years, if the world stays silent when a bomb drops on the same site of Babyn Yar?"

The New York Times reports that Jewish groups and institutions around the world condemned the strike.