Why Do Coupons Say They Are Worth 1/100th Of A Cent?

Much of life in this modern era is governed by "the fine print." Fail to read a contract thoroughly, including (especially) the fine print, and you may find yourself owing outrageous interest charges or various other penalties, and you may further find that there's next to nothing you can do, legally, to make things right. Other examples of fine print are downright inconsequential: for example, you may be familiar with the old canard that your mattress has a tag on it that's illegal for you to cut off. In fact, according to FindLaw, that's for manufacturers and retailers, not consumers, so go ahead and cut off mattress tags (your own, anyway) to your heart's content.

Another area where meaningless (to the consumer, anyway) fine print plays a role is in the realm of paper coupons. Look closely and you'll see that it contains a disclaimer to the effect that it has a cash value of one hundredth of a cent — such a trifling amount of money that you may wonder whatever compelled the coupon's printer to include that bit of legalese.

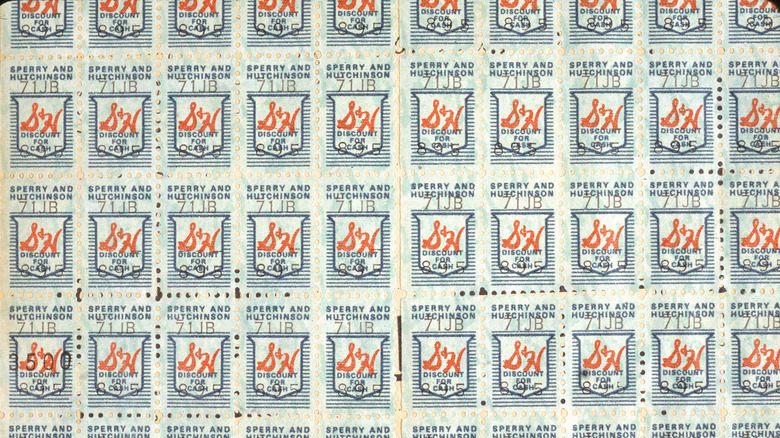

The loyalty stamps economy sets the stage

To understand the reason why printers put a cash-value disclaimer on coupons, you must first understand their predecessor: loyalty stamps. They haven't really been a thing since the 1970s. As Antique Trader explains, the stamps worked like this: The customer would spend a certain amount at a store (say, $100 in groceries), and would get a certain amount of loyalty stamps in return. Save up enough stamps, and you could purchase something with them from a catalog, such as a toaster or a clock. Antique Trader tells the story of Pennsylvania school children who dreamed big, saving up enough stamps — 5.4 million — to purchase two gorillas, one each for the zoos in Pittsburgh and Erie.

However, as a 2011 posting at Mental Floss explains, the stamps were a racket. The cost of that "free" swag in the catalogs was actually being passed onto consumers, something that state governments wised up to, eventually passing laws assigning a trifling cash value to the stamps, allowing customers to skip the catalog all together and instead redeem their stamps for cash. What does this have to do with coupons?

States considered loyalty stamps and coupons the same thing

Coupons and loyalty stamps are not the same thing. However, they're both paper vouchers utilized in the buying and selling of retail goods, and as such, according to Mental Floss, various state governments have treated them the same way when it comes to writing laws that govern them. Officially, only three states have such laws these days, but since coupon printers don't want to waste time printing one set of coupons for Indiana, Utah, or Washington and another for the other 47 states, they just put the disclaimer on all of them. Further, there's no industry "standard" when it comes to cash value; some coupons may disclaim that they're worth 1/10th, 1/20th, or 1/100th of a cent.

So can you save up 10, or 20, or 100 coupons and redeem them for a penny? As it turns out, the answer isn't as simple as "yes or no," as Couponing 101 reports. Though the coupons may have a "value," however trifling, printed on them, there does not appear to be a mechanism by which a consumer can convert that cash value. No address to send them (and you'd wind up losing money on the transaction anyway when you purchased a stamp), no central office you can call, and your local grocer isn't going to accept 20 coupons and give you a penny — at least, as Mental Floss explains, there are no verifiable examples of anyone trying it.