The Untold Truth Of The Kremlin

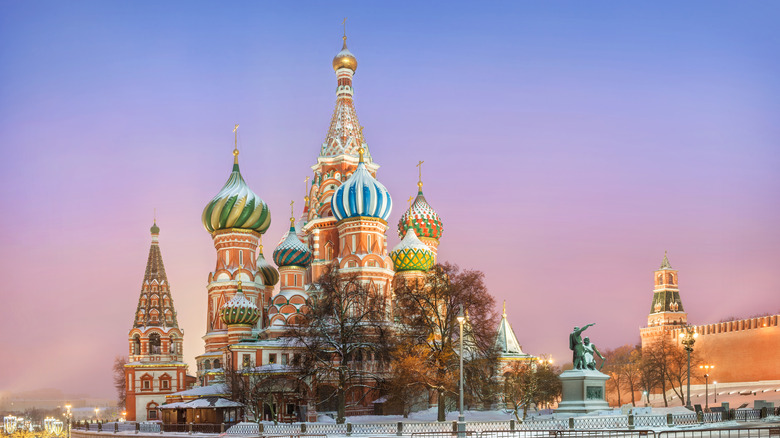

The Moscow Kremlin is one of the most iconic fortresses in the world. Although this may sound cliche, the onion domes of St. Basil's Cathedral, Red Square, and the brick towers of the fortress walls are easily recognizable in books, magazines, and on television. In fact, as The Spectator noted, it is hard to imagine Moscow without the Kremlin. It seems timeless – as if it has always been there.

The reality is that the Kremlin has been built, rebuilt, and added to many times over its 800-year history. From its earliest beginnings as a primitive wooden fort to the magnificent brick-and-stone architecture of today, the fortress has seen wars, fires, looting, and miracles that all contribute to that magical aura of today. The fortresses' tales and urban legends, often preserved by word and mouth are truly "untold," and are absent from the average history book. These tales make the Kremlin a fascinating subject for paranormal, subterranean, and history enthusiasts, who have spent their lives uncovering the fortress' untold secrets with varying degrees of success. Here are just a few of the Kremlin's untold stories.

'Kremlin' is of uncertain origin

The word "kremlin" was borrowed into the English language, according to the Online Etymological Dictionary via French. The modern Russian equivalent is simply "kreml," but an older form "kremlinu" is attested as well. The origins of the word however, are unknown, possibly deriving from older Slavic terms or the Tatar language.

In the 17th century, the word entered Western European languages as "cremelena," appearing in this form in the 1684 book "The voiages and travels of John Struys” and Jocolus Cruli's 1698 Antient and Present State of Muscovy. Their transcription differs from the modern Russian "kreml" and Cruli specifically noted that "cremelena" was the native Russian name for the citadel – or at least an attempt to phonetically transcribe the Russian in Latin letters. The transcription suggests that the Russian form "kremlinu" or perhaps "kremlina" was still in use. Foreigners heard it as "cremelena" and used it to describe the Moscow Kremlin. But in Russian, the word refers to a generic citadel in a city and there are other kremlins as UNESCO notes, such as the famous Kazan exemplar (above).

Eventually, according to the OED, the word passed into French as "kremlin," and replaced "cremelena." English borrowed it by 1796. Today, there are two principal meanings, which refer either to the Russian government or to the Moscow fortress containing the iconic Red Square and St. Basil's Cathedral.

The Moscow Kremlin is a small city

A quick image search for "kremlin" will bring up photos of the onion-domed St. Basil's Cathedral with Red Square in the foreground (above). This image is frequently associated with the Kremlin, but it is only a small part of it. As noted earlier, Kremlin means "citadel," and is virtually a small city unto itself.

As the University of Pennsylvania notes, the Kremlin is a fortress complex within Moscow surrounded by a large wall and towers. Inside the walls were the homes of the Muscovite nobility and grand princes. According to the Kremlin Museum, Moscow's streets historically converge on the Cathedral Square, where, as the name suggests, three cathedrals stand. Nearby is a fourth cathedral, the famous St. Basil's, along with several smaller churches and the old Palace of the Patriarch, the residence of the patriarchs of the Russian Orthodox Church before 1917. The Kremlin Arsenal is the only remaining building attributable to Tsar Peter the Great and has an unfortunate history. This building, which took 34 years to build, was finally completed in 1736. Unfortunately, it burned down in 1737 and had to be rebuilt.

Today, the citadel's most important building is the Grand Kremlin Palace. Originally built in the mid-19th century under Tsar Nicholas I, the building today serves as the residence of the President of the Russian Federation, Vladimir Putin.

Italians built a lot of it

According to UNESCO, the Kremlin began as a small fortified area in the 12th century and eventually became the residence of Moscow's grand princes. It did not, however, take on its current design until the 15th century. According to Russia Beyond, Grand Prince Ivan III had a love for all things Italian. The prince wanted to beautify Moscow, so he turned to Italy's top talent to bring the magnificence of the Italian Renaissance home. Ivan's representatives found their man in architect and engineer Rodolfo Fioravanti, who at the price of 10 rubles a month (enough to buy 10 houses at the time!) merged Italian design with traditional Russian style to create the magnificent fortress that stands today.

During his decade-long Russian sojourn, Fioravanti rebuilt the collapsing Dormition Cathedral (above) and erected the magnificent Palace of the Facets, which became the tsars' primary social venue. Fioravanti and several Italian compatriots also designed the Kremlin's towers, whose brick-faced exterior likely drew upon existing architecture in northeastern Italian cities such as Verona. Thus, one can say that the biggest Italian fortress in the world is not in Italy – but in Russia!

Fioravanti contributed another building to the Kremlin – an artillery foundry. These pieces were used to devastating effect against Muscovy's less-advanced Novgorodian and Tatar neighbors and enabled the unification of European Russia under Muscovite rule. Fioravanti's legacy survives today, as per RFERL, President Vladimir Putin continues to hire Italian architects to design and build his personal projects.

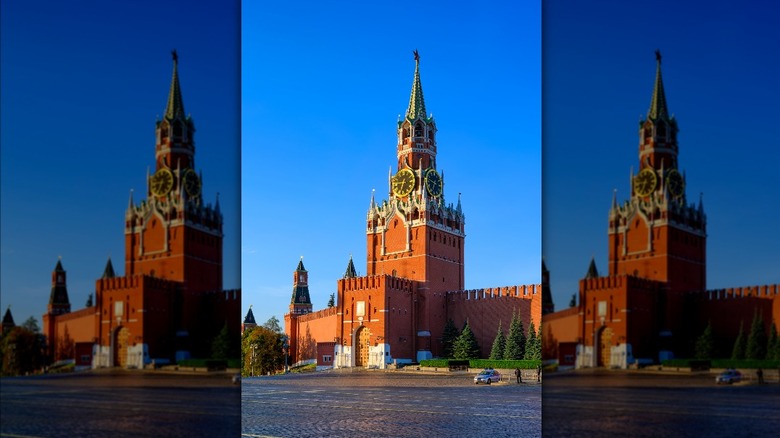

The Gate of the Redeemer withstood Napoleon

According to Edna Walter's 1910 book "Peeps at Many Lands: Russia," not far from Red Square stands a gate known in English as the "Gate of the Redeemer" (a.k.a. Spasskaya Gate in Russian, above) The gate drew its name in homage to the icon of Christ the Redeemer that looked down upon people as they entered the Kremlin through this particular gate. Out of respect for the icon, people removed their hats. Locals called out those who did not.

Walter recorded that an old man sat under the gate selling votive candles and regaling passersby with tales and legends of the gate, which the Icon of Christ imbued with a supernatural aura. The icon had allegedly forced invading Tatars to turn back after it filled Moscow with smoke, but French emperor Napoleon Bonaparte and his troops probably were unaware of this when they confronted the icon in 1812.

According to Walter's elderly interlocutor, Napoleon was no match for Jesus Christ. During Napoleon's 1812 Invasion of Russia, French forces occupied Moscow. Upon arriving at the Redeemer Gate they tried to reach the icon – presumably to steal it – with ladders, only for them to snap in half every time. French soldiers then tried to blow it up with artillery, but the powder inexplicably got wet every time. When they finally got the cannon to fire, it exploded and killed all the gunners. The icon was left completely untouched. Napoleon may have been master of Europe, but he was clearly no match for God Himself.

St. Jonah told Napoleon to beat it

Russian legend tells that after his defeat at the hands of the icon of Christ the Redeemer, Napoleon soon had another supernatural encounter inside Moscow's Cathedral of the Assumption. According to "Peeps at Many Lands: Russia," author Edna Walter recorded that the verger of Moscow's Assumption Cathedral would point curious travelers towards the exact spot where Napoleon had slept. The French emperor's occupation (above) and presence were considered violations of this sacred space, which preserved the relics and bodies of important Orthodox saints. Walter recounts that one day, Napoleon was looking at the relics of St. Jonah the Metropolitan, including his preserved body. Suddenly, the body lifted one of its fingers. The "Master of Europe," as he was called, fled the cathedral in terror.

Had Napoleon received this treatment for merely sleeping? Walter is silent on that, but Russia Beyond notes that Napoleon was guilty of far more than just sleeping. Napoleon's army had thoroughly plundered Moscow's churches, looting around 300kg of silver. Napoleon had gone into the Cathedral of the Assumption to loot St Jonah's relics, supposedly the last valuables left inside the Kremlin. But as Napoleon stood there, the saint himself appeared angrily shaking his fist at the emperor. Terrified out of his mind and perhaps fearing eternal punishment, Napoleon left the treasure untouched. As the French army retreated from Russia, the silver was recaptured and used to fashion an ornate chandelier that hangs in the Cathedral of the Assumption today.

It allegedly hosts a buried library

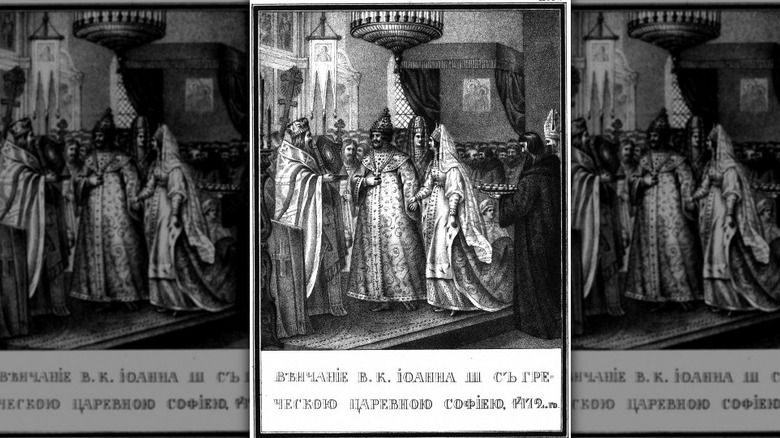

According to Britannica, Ottoman Sultan Mehmet II captured Constantinople in 1453. The last Byzantine emperor Constantine XI Palaiologos was killed in battle. But as Russia Beyond notes, his brother Thomas escaped to Rome, allegedly with the Byzantine imperial library. This precious collection contained at least a millennium's worth of books. How he did it (if he did it) is a mystery, but this legendary deed is the basis of Russian tsar Ivan the Terrible's "Libreya."

In Roman exile, Thomas fittingly married off his daughter Sofia to Muscovite ruler Ivan III (above), the man who brought Italy to Russia. Sofia's dowry included the library, which eventually passed to her grandson Ivan IV (a.k.a. "the Terrible"). The tsar expanded the collection, which supposedly included books extant today only in fragments. The only problem? No one has ever found the collection

Scholars and enthusiasts searched Ivan's favorite haunts outside Moscow in vain, so attention turned to the capital. A rumor circulated that the tsar had buried the library under the Kremlin, per the Journal of Library History. Subsequent investigations by tsars, scholars, and even Joseph Stalin all came back empty-handed too. Thus, it was assumed that the books either burned in a fire, were eaten by occupying Polish soldiers, or are still buried under the Kremlin. Only Baltic German historian Christian von Dabelov (allegedly) saw the list of books in the library of the University of Pernau. But when he went to copy it, he claimed, it had mysteriously disappeared. Thus, the "Libreya" remains a popular urban legend.

Our Lady of Vladimir saved it from looting

In the same vein as the previous supernatural miracles, it is said that one of the most famous icons of the Eastern Orthodox world saved the Kremlin from being sacked several times. According to the University of Dayton, the icon of Our Lady of Vladimir is a world-famous icon that was commissioned in Constantinople and found its way into the Rus' lands in the 12th century.

According to Russia Beyond, the icon is said to have saved Moscow from falling victim to the Turco-Mongol warlord Timur-e lang, better known in Europe as Tamerlane. With Tamerlane's body count rumored to number in the millions (per "The History of the Mongol Conquests"), it is no surprise that the desperate Muscovites sought Our Lady of Vladimir's aid. It is said that once the icon was brought to Moscow, the Virgin Mary appeared to Tamerlane and ordered him to turn back. He did, and Moscow was spared.

In 1521, Moscow faced another potential sack, this time by Mehmet Giray's Crimean Tatars. Despite the icon's miraculous reputation, Muscovite authorities ordered it removed from the city for safekeeping, lest the Tatars desecrate or destroy it. But one nun denounced the decision. Per her vision, the icon had to stay inside the Kremlin. Her orders were followed, and the Tatar army inexplicably returned home. Once again, the Muscovites' faith had seen them through their darkest hours.

The communists demolished much of it

According to the Russian Presidential Library, Vladimir Lenin's Bolsheviks moved the capital back to Moscow in 1918 following their violent seizure of power the year before. However, the Kremlin was covered in symbols of the old Imperial Russia, including churches, tsarist monuments, and lots of Christian iconography that ran counter to state-sponsored atheism. Thus, Lenin and his successors set about destroying the offending monuments.

Most of the destruction, per Russia Beyond, took place under Joseph Stalin. Under his watch, monuments such as the chapels of the Gate of the Redeemer (Spasskaya Gate) and several other smaller churches were demolished. The Nikolaevsky Palace, the birthplace of Tsar Alexander II, was blown up too. Even the Cathedral of Christ the Savior (above), located just outside the Kremlin, was not spared. The damage to Russia's cultural heritage was incalculable. The demolitions, per one observer (via RFERL), constituted an attempt to erase Russia's past, which made the Bolsheviks extremely unpopular.

Much of the building material, per Atlas Obscura, was recycled to build the Moscow Metro system, which still stands today. This is why Moscow subway stations are so grand compared to their drab American counterparts. They were built with the finest material available.

It connects to Metro-2 (supposedly)

In 2005, the BBC reported on a group of Russian underground enthusiasts looking to uncover the secrets of Moscow's alleged Metro-2 line. The head of the group, a man named Eugin, claimed to have seen the line and had photographic evidence to back up his claims. Now, there was no way to confirm his photos nor did Eugin say how he got in. But since the FSB detained a journalist for simply writing about it, Eugin's story probably had some truth to it.

So what does Metro-2 have to do with the Kremlin? According to Atlas Obscura, Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin built the secret subway line to evacuate the Soviet government from the Kremlin in an emergency. Allegedly, the line, which also connected the Kremlin to the Ministry of Defense and bomb-proof bunkers let out near Stalin's country dacha, providing a secure way to escape the city in case of a siege.

Rumors continue to swirl about Metro-2, in particular rumors that it connects the Kremlin to an underground military base called Ramenki that can host 30,000 people. According to Russia Beyond, the line exists, but no one, not even the highest levels of the Russian intelligence services, knows its full extent. Officers supposedly only have clearance to certain parts that they are responsible for. Although this article is about the Kremlin's "untold truth," it is impossible to determine the "truth" of Metro-2 and its relation to the Kremlin when even the people who work there have no idea.

Poland-Lithuania occupied it in 1609

Although the Kremlin avoided several sacks, presumably due to divine intervention, luck or Providence sometimes left it to the wrath of Russia's enemies. After the death of Ivan the Terrible, Russia gradually degenerated into the Time of Troubles, a chaotic period marked by internal feuds over the throne. Seeing an opportunity to weaken its Russian archrival, Poland-Lithuania attempted to elevate candidates amenable to its interests in view of turning Russia into a puppet state. Polish king Sigismund III came close to success in 1609. According to Russia Beyond, he successfully installed his son Vladislav on the Russian throne. The new tsar would convert to Orthodoxy, respect the Russian Orthodox Church, and keep Poland and its armies out of Russian affairs. But once the deal was done, Sigismund reneged and seized the Kremlin by force.

The Polish garrison proceeded to loot Moscow, desecrate churches, and rob civilians. Eventually, civilian anger escalated into an uprising that drove the Poles back into the Kremlin. The starving soldiers allegedly turned to cannibalism and eventually surrendered. It was a costly defeat for Poland, which had failed to subjugate its biggest rival. The failure would return to haunt the Poles in 1772, when Russia, alongside Austria and Prussia, ended the country's existence with a tripartite partition.

It was demoted in the 18th century

Russia, according to the Arts Society, was still considered a world away from Western Europe, despite a shared Christian religion (albeit in different forms). While in Western Europe, the aristocratic members of the sexes mixed, Russian noblewomen lived in seclusion, as in the Middle East. Catherine Merridale's "Red Fortress," meanwhile, notes that the Kremlin, for all the external grandeur, was dark and foreboding inside, lacking even the most basic administrative equipment to keep the realm running.

Tsar Peter the Great, who had traveled and studied in Western Europe incognito, decided that Russia needed a westernization campaign. The tsar shaved his beard (having one was an Orthodox tradition), taxed others for the privilege of growing one, banned Muscovite court dress in favor of Western European styles, and brought noblewomen out of seclusion. According to Russia Beyond, French soon replaced Russian as the lingua franca of the court and Russian nobility went abroad to study it.

According to History Today, Peter demoted the Kremlin itself in 1702 in favor of a new capital in the malaria-ridden swamps at the mouth of the Neva River. Following Russian tradition, he turned to Italian architect Domenico Trezzini, who built the magnificent city of Saint Petersburg. The tsar took up residence in the Peterhof Palace (above). The new city, built on 350 islands, quickly earned the nickname "the Venice of the North" and the Kremlin became an afterthought.

Eastern Europe's fate after WWII was nearly decided there

In 1944, Winston Churchill attempted to preserve British primacy in Europe in a negotiation over spheres of influence with Joseph Stalin's USSR that cut out any American participation. The result was the so-called "Percentages Agreement," worked out at the Moscow Conference inside the Kremlin itself. Writing in the American Historical Review, Professor Albert Resis explained that Churchill claimed that Stalin agreed to divide Eastern Europe by percentage. Some countries were split 50-50, others 90-10, and some were given completely to one side or the other.

It is unclear how the agreement was supposed to function, but in practice, it gave Stalin free reign over Romania and Bulgaria, where the Red Army promptly installed communist governments. Churchill in return received Soviet guarantees not to subvert British interests in the Mediterranean. Thus, the British-backed Greek monarchy successfully fended off a communist insurgency. Unfortunately for Churchill, he did not get his other demand, an Anglo-American invasion of Yugoslavia, which allowed the country's communists to seize power.

The agreement overwhelmingly benefited Moscow. The Red Army occupied Eastern Europe while Britain was powerless to enforce its interests there, especially when its American ally denied support. The United States soon replaced Britain as the dominant force in Europe, the Percentages Agreement was scrapped, and the stage for the Cold War was set.