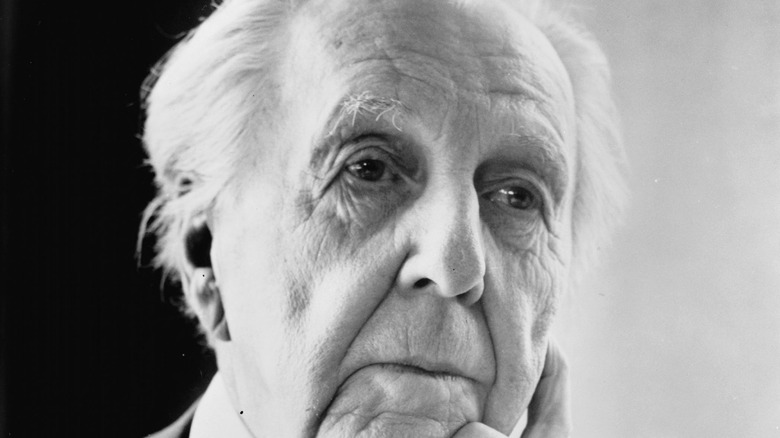

Tragic Details About Frank Lloyd Wright

Frank Lloyd Wright is likely America's best-known architect. Recognized for the creation of the Prairie style of architecture — characterized by horizontal lines and making sure the architecture is suited to the environment, according to the Frank Lloyd Wright Trust — Wright eventually became a successful architect, even if he didn't start out that way. His childhood was poverty-stricken, and he set out for Chicago at a young age to look for work.

Beset by a long series of tragedies throughout his life, Wright was constantly attempting to get caught up financially, as well as receive commissions for the next great project. Some of his best and most well known work (such as Fallingwater in Pennsylvania) was done late in his career, and hundreds of his designs were actually never built.

Wright traveled extensively throughout his life, and he developed a fascination with Japan and Japanese art. Part of his travels to Europe and Japan were to get away from his first wife, who refused to grant him a divorce for several years. However, even when he came home again, trouble and tragedy followed, including murder, fires, and financial disasters. Therefore, let's take a look at the tragedies of American architect Frank Lloyd Wright.

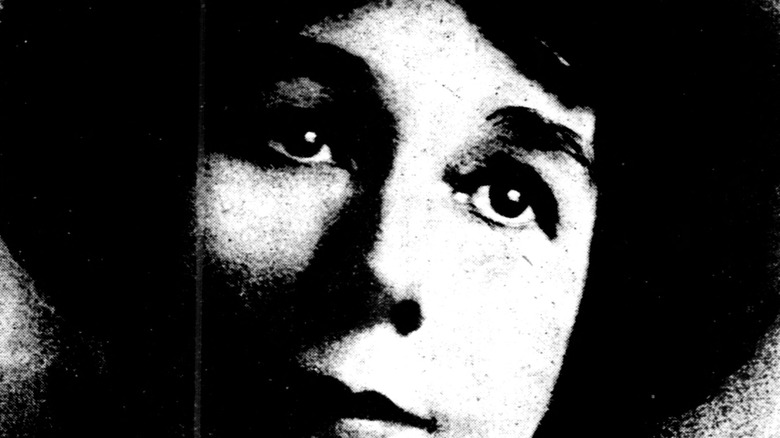

Mamah Cheney and her children were murdered by a staff member at Taliesin

On August 15, 1914, Frank Lloyd Wright's mistress Mamah Cheney, her two children, and six others (Wright's employees, as well as an employee's son) were attacked with an ax wielded by Wright's handyman, Julian Carlton, while staying at Wright's Wisconsin estate of Taliesin, writes Crime Museum.

Cheney, her children John and Martha, and four others were either killed or died of their wounds. Only two employees, William Weston and Herbert Fritz, survived, writes World History Project. The only known photograph of Cheney was published after her death, according to Wisconsin History. Carlton also set the property on fire, and he later died in custody (via the Independent).

After the dust had settled, Wright wrote of the fire in his autobiography, "Frank Lloyd Wright": "So the rage that grew in me when I felt the inimical weight of human censure concentrated upon me began to fade away until I finally found refuge in the idea that Taliesin should live to show something more for its mortal sacrifices than a charred and terrible ruin on a lonely hillside in the lovely ancestral Valley where great happiness had been." Carefully, clearly thinking of the happier past rather than the future, Wright began to rebuild his estate. But the property also burned again in 1925 after an electrical fire, and it was ultimately rebuilt twice, according to Taliesin Preservation.

His buildings have been destroyed by disasters and demolition

In the years since Frank Lloyd Wright's death, several of his buildings have been destroyed by fires and other natural disasters. Others have been deliberately demolished. For example, his famous work of Fallingwater was damaged in 2017 from flooding in the area, writes Arch Daily. A log picked up by the rushing river, Bear Run, damaged a cast bronze sculpture, Jacques Lipchitz's "Mother and Child," that had been installed soon after the property's completion in 1939. "It's one of our most significant works here at Fallingwater," Lynda Waggoner, Fallingwater's director, said to the Associated Press (via Arch Daily). "The first view, when you're on the bridge, looking at the house — it's right there."

In 2018, Wright's Lockridge Medical Clinic in Montana was demolished, despite being listed on the National Register of Historic Places, writes Arch Paper. The Montana Preservation Alliance and the Frank Lloyd Wright Building Conservatory worked together for a year to try and raise the funds the owner said he would accept in lieu of destroying the building. The building conservatory says that their realistic offer was rejected, and demolition proceeded. According to owner Mick Ruis' lawyer, the demolition had already been delayed once before moving ahead.

The buyers of one of Wright's cottages in Illinois asked for it to be demolished just two weeks after purchasing the property in 2019, writes Hyperallergic. The cottage was known for Wright's style of horizontal lines and a flat roof.

Wright's second wife was a chaotic addict who possibly had him arrested

Frank Lloyd Wright's second wife, Miriam Noel, was an artist who connected with him over loss after the murder of Mamah Cheney, writes The Art Story. After he entered a relationship with her in late 1914, he learned that she was a morphine addict, not to mention violent. Wright married Noel the year after his divorce from his first wife was granted, hoping that marrying her would improve their relationship. This didn't come to pass. Wright and Noel were married for four years, though they separated early on. It took several years to finalize their divorce, which she finally granted in 1927 (via The Art Story).

Even in the middle of their divorce proceedings, Noel continued to harass Wright. She admitted to drawing a gun on him, while he called her "vile, vulgar, indecent and abusive", writes the Independent. She allegedly engineered Wright's arrest in October 1926 for violating the Mann Act, which was intended to fight forced sex work (via NPR). Wright had already been with his eventual third wife, Olgivanna Hinzenberg, at the time; the couple had fled to rural Minnesota using fake names in September, according to the New York Times. Still, Wright was released the day after the arrest (via Minnesota Historical Society).

If you or anyone you know is struggling with addiction issues, help is available. Visit the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration website or contact SAMHSA's National Helpline at 1-800-662-HELP (4357).

The 1920s were a time of financial troubles for Wright

Frank Lloyd Wright moved to the U.S.'s west coast in the 1920s, hoping that commissions would follow after his work in Europe and Japan. The Imperial Hotel, which he completed in Tokyo in 1922, survived the Great Kanto Earthquake the next year, and Wright, gleeful of his success, was sure that commissions would flood in, according to The Art Story. However, little work came his way, and Wright returned to Wisconsin. Trouble followed, as the bank foreclosed on Taliesin while he was rebuilding after an electrical fire in 1925 (via Library of Congress). Though the house was insured, it did not repay for everything (particularly, the art) that had burned, writes the Independent. Wright, never good at handling money, was eventually evicted.

His career continued to flounder, and his finances got worse. Friends and even former clients began to bail him out. In the late 1920s, he was forced to sell what was left of his personal beloved Japanese art prints, according to the Library of Congress. Commissions continued to fail before they began, and finally the stock market crash of 1929 destroyed Wright's last commission: an Arizona resort (via The Art Story).

Hundreds of his designs were never realized

Only around half of the buildings Frank Lloyd Wright designed were actually built. He designed many buildings during periods of low commissions, such as the 1920s, so they never came to pass. In 1912, he designed his first skyscraper, but it was never built, writes Britannica.

Given the size of his portfolio, not to mention the length of his career, other organizations have attempted to carry on his work in some form, trying to save it from being lost. Spanish architect David Romero created some of the unbuilt designs in digital 3D, so people could see what they were actually supposed to look like, writes the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation. Romero said of one design, the Gordon Strong automobile objective: "It is a pity that it could not be built. If it had, I think it would be one of his most celebrated designs." (via Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation).

On top of that, the Frank Lloyd Wright Revival Initiative aims to rebuild Wright's torn down projects and build the projects that were never fully realized (via Architect Magazine). Their first project was to rebuild a park pavilion in Banff, Canada, one of only two structures Wright built in that country; unfortunately, their project stalled out by July 2021, writes the Globe and Mail. The organization is currently focused on other rebuilding projects, such as the Arch Oboler complex, which was destroyed by fire in 2018 (via the Frank Lloyd Wright Revival Initiative).

Wright was divorced two times

Frank Lloyd Wright was married three times, and he divorced twice. He was married for the first time to Catherine Lee Tobin at the age of 22 when he was living in Chicago. He was still working as a draftsman, and that work kept him grounded to his marriage. Wright built up his architectural business while married to her, and they had six children over the course of their two decades of marriage (via How Stuff Works).

Eventually, however, Wright began to get restless. To get away from his wife and family, Wright fled with his lover Mamah Cheney to Europe and Japan for a number of years, beginning in 1909. Despite having left her and their family, Catherine refused to grant him a divorce for a period of years, until 1923, writes How Stuff Works.

After Catherine finally granted Wright a divorce, he married for the second time a year later. His second marriage, to Miriam Noel, was fraught with deceit and chaos. Noel accused him of having affairs, which given his history, is certainly a possibility, writes The Art Story. They separated early in their marriage, and Noel finally granted Wright a divorce after four years, in 1927. As might be expected, Wright quickly found another lover in Olgivanna Hinzenberg; they met in 1924 and married four years later.

Wright's childhood was marred by poverty and abandonment

The Wrights were not rich, and they moved often in Frank Lloyd Wright's younger years as his father moved from one position to another across New England, including Rhode Island and Massachusetts. His father, William Carey (also known as Cary) Wright, was a preacher and musician, and his mother, Anna Lloyd Jones, was a teacher, writes the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation. His autobiography mentions many periods of disquiet in their home and a few times when he would run away, only to be caught by his aunts and uncles (via "Frank Lloyd Wright"). "Frank Lloyd Wright: A Life" writes that William Wright was not good with money, and young Frank recalled living in poverty, with little food gracing the table.

His parents eventually divorced when Wright was 18; Wright later claimed that he never saw his father again (via "Frank Lloyd Wright"). To support himself and his mother, Wright worked as an assistant to the department of engineering dean at the University of Wisconsin, writes the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation, all while working on an engineering degree, but he never finished it. At the age of 20, Wright instead left to seek his fortune in Chicago.

Wright's independent work cost him his mentor and friend

Frank Lloyd Wright quickly found work in Chicago at Adler and Sullivan's. He came to regard Louis Sullivan as a great teacher, and he was given enormous responsibility over designs (via "Frank Lloyd Wright" and "Years with Frank Lloyd Wright: Apprentice to Genius"). A blending of Wright's and Sullivan's styles is easily seen in certain commissions from this period of time.

But while under contract with Adler and Sullivan's in the late 1880s and early 1890s, Wright accepted seven private house commissions independently (via "Lost Wright: Frank Lloyd Wright's Vanished Masterpieces"). When Sullivan found out about this, despite Wright's best efforts to keep it from him, he charged Wright with breaking his multi-year contract; Wright either left the position or was fired. Regardless, this incident cost him a great mentor and friend in Sullivan, who inspired his well-known Prairie Style, writes the Frank Lloyd Wright Trust. The two men didn't speak for the next 12 years.

Wright's adopted daughter and grandson died in a car accident

In 1946, Svetlana Peters, Frank Lloyd Wright's step-daughter by his third wife Olgivanna, and her young son Daniel died by drowning after their car fell off a bridge in Wisconsin while on their way to Spring Green, writes Newspapers. They both died on the drive to a Madison hospital. Peters' older son Brandon (also known as Brandoch) managed to get out of the car and ran to get help; a passing driver was then able to shift Peters and Daniel out from underneath the car.

Her husband, William Wesley Peters, was one of Wright's first apprentices and was an architect as well; the couple was married in 1935, according to AP News. But Peters was a gifted artist in her own right, a fact only discovered decades after her death when her artwork was found and displayed in 2014 at the Wyoming Valley School Cultural Arts Center, which was designed by Frank Lloyd Wright. In addition to being a painter and illustrator, she also organized the Taliesin choir and played piano and violin, writes The Dodgeville Chronicle.

Wright's body was eventually cremated, against his wishes

Frank Lloyd Wright wanted to be buried in Wisconsin, which he originally was, in 1959. However, decades after his death, in March 1985, his body was removed from his grave and cremated due to the desires of his third wife Olgivanna, which was for their ashes to be stored together in Taliesin West, their home and estate in Arizona, thousands of miles away (via the Independent). His daughter Iovanna signed the paperwork requesting the exhumation, standing firm against many who wrote against the move. After the ashes were stored for many years, a memorial garden was built in the Wrights' honor at Taliesin West, though it isn't open to the public.

Despite backlash, his ashes have not been returned to Wisconsin. Wright's son David considered the act "grave-robbing." Wisconsin officials wrote that, "Much more than ashes have been taken from Wisconsin — the citizens of the state have lost one evidence of our history, spirit and genius." Nonetheless, the Wisconsin grave that bears Wright's name lies empty, and it likely will continue to do so.

Frank Lloyd Wright was an art dealer, but he had his reputation ruined

When he was young, Frank Lloyd Wright earned money as an art dealer of Japanese wood block prints; he was fascinated with work from the Edo period his entire life (via Hammer Museum). In 1920, however, it was discovered that he was tricked by another dealer and sold forged prints, writes The New Yorker.

Certain methods were used to ensure the faded prints stayed artificially bright, such as using pins to compare colors. In an attempt to salvage his reputation, Wright sued Tokyo print dealer Kyūgo Hayashi for the doctored prints; Hayashi was sentenced to a year in prison (via Hammer Museum). Wright, however, was also known for "fixing" prints with colored pencils and crayons.

In the depths of the Great Depression, however, Wright continued to work as an art dealer for Japanese woodcuts, and he made more money during these years than he did as an architect, notes The Art Story. He continued to hold onto a personal collection of Japanese wood block prints throughout his life.

A devoted fan took his own life after Wright's death

Seth Peterson grew up near Taliesin, in Black Earth, Wisconsin, writes Curbed, and he visited the area frequently. (Interestingly enough, Peterson also shared a birthday with the architect.) Despite his passion, he failed to qualify as one of Frank Lloyd Wright's apprentices after Taliesin opened to students in the 1930s, but he decided to ask Wright to design a cottage for him in 1959. Allegedly, Peterson simply sent Wright a check, which the constantly cash-strapped architect promptly cashed, meaning he had also accepted the commission for the cottage.

Later that year, however, Wright died. In early 1960, with the project nearly finished, Peterson committed suicide, depressed both over Wright's death and his own personal problems.

The cottage is only 880 square feet, and it's still open for visitors today (via the Cottage for Mr. Seth C. Peterson). It was Wright's last project in Wisconsin, though he didn't live to see its completion. In 1966, the state of Wisconsin bought the property, though it was unused and eventually fell into disrepair. In 1989, Frank Lloyd Wright fans formed the Seth Peterson Cottage Conservancy to restore the structure. It has continued to be updated as the years passed.

If you or anyone you know is having suicidal thoughts, please call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-TALK (8255).