What Happened To Dorothea Puente's Victim Benjamin Fink?

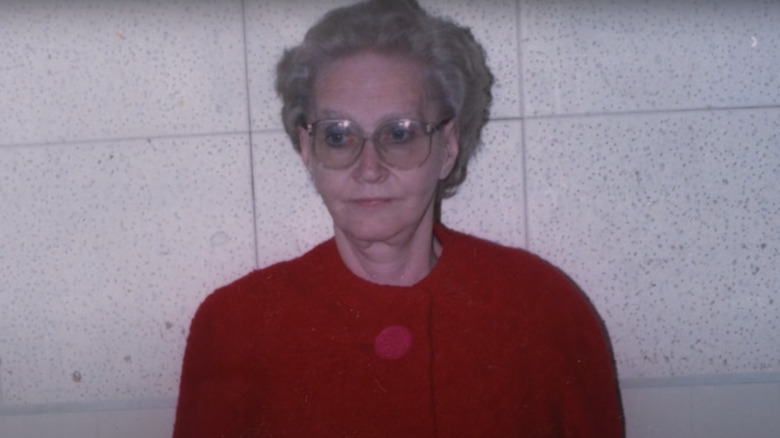

At first glance, Dorothea Puente seemed like the perfect person to care for California's most vulnerable. She had the appearance of a sweet grandmother — tidy gray hair, big thick-rimmed glasses, colorful dresses — and a caring firmness that suggested she could lay down the law, if needed. That's why social workers and other welfare agencies would often bring some of their toughest cases to Puente's boarding home at 1426 F Street in Sacramento. Between 1982 and 1988, Puente would take in some of the state's most at-risk individuals: the homeless, the chronically ill, the elderly, those struggling with mental illnesses, and people battling seemingly incurable levels of alcohol and drug addiction.

What those social workers didn't realize is that Puente had a dark past and was running a deadly operation out of her picture-perfect Victorian bungalow. Throughout the 1980s, Puente would take advantage of her tenants who lived on the fringe, knowing they'd go unnoticed. She'd gain their trust, take control of their finances, forge their Social Security and pension checks, and, in many cases, poison and bury them on her property, according to All That's Interesting. By the time she was finally caught in 1988, Puente had her cold-blooded serial killer methods and coverups down to a science that would net her $5,000 a month, per Sactown Magazine.

Who was Dorothea Puente?

Dorothea Puente was born Dorothea Helen Gray in Redlands, California in 1929, and lived a traumatic childhood. Her alcoholic parents both died when Dorothea was young, leaving her separated from her siblings and shuffled between foster homes, where she suffered sexual abuse, according to the Los Angeles Times. By the time she was 16 years old, Puente relied on sex work for income, per Bustle. Before long, Puente began stealing and forging checks, which periodically landed her in jail.

She married four times, the first of which was when she was just 16. Her second husband had her committed to a psychiatric ward after claiming she had been suicidal, unfaithful, and that she gambled his money away under a constant fog of drunkenness. In 1960, she was arrested for owning and operating an illegal brothel under the cover of a bookkeeping firm. In 1968, she married Roberto Jose Puente, but separated a little more than a year later under turbulent conditions, but she kept his name, per ScreenRant. Shortly after their separation, she opened an unlicensed alcohol rehab boarding house at 21st and F Street in Sacramento, which was shut down after she was charged and convicted of illegally cashing government checks that belonged to her tenants. But that didn't stop her. Within a few years, she opened her now-infamous second boarding home just a few blocks away at 1426 F Street.

Who was Benjamin Fink?

On March 9, 1988, Sacramento social worker Peggy Nickerson placed Benjamin Fink — a 55-year-old chronic alcoholic — at 1426 F Street. According to Ryan Green's book, Buried Beneath the Boarding House, Fink would eat communal meals with the other boarders, but otherwise kept to himself. From years of living on the street, Fink had developed a number of health issues, including pneumonia, and mobility problems from a car accident requiring him to use a cane. Fink often appeared in emergency rooms to get treatment for injuries he suffered while heavily intoxicated, according to court documents (via Casetext). On other occasions, he would check out of the hospital against the doctor's wishes. Just days before he was placed at Puente's home, Fink had been disqualified as a plasma donor — which had been a source of income for him — on account of "general feebleness."

In other words, Fink was the perfect target for Puente. She would often confine Fink to bedrest with as little as a runny nose, and, against her own rules, would bring meals to his room leaving her free to drug his food and drink without suspicion. Fink lived at the boarding home for nearly two months, and his brother visited with him most weeks, according to court filings. One day, while Fink was heavily intoxicated at the residence, Puente said that she "was going to take Ben upstairs and make him feel better," per ScreenRant. It was the last time anybody saw Fink alive.

Tenants could smell death at 1426 F Street

A few days after Puente helped Fink upstairs, a tenant complained to Puente of a horrific odor, which he later described to police as the "smell of death" coming from a room off the kitchen. Puente brushed it off, according to court documents (via Casetext) saying the sewer had backed up. She would later tell boarders and, eventually, the police that Fink had moved back to his family's home in nearby Marysville after she told him "not to ever come back on the property" because she "couldn't take his falling down drinking any more."

Nobody pressed the matter further because individuals with the kinds of problems Fink had picked up and left all the time, and Puente was banking on those assumptions. For months after his disappearance, Puente forged the signature on Fink's Social Security checks, and collected other benefits in his name — more than $6,000 in total, according to court records. But that all came to an end when one tenant, Alvaro Montoya who went by "Bert," went missing in late 1988. As reported by the Los Angeles Times, Montoya's social worker wasn't buying Puente's mixed up story as to his whereabouts and called the police. On November 11, 1988, an initial police visit didn't turn up any evidence of wrongdoing, but as the police were about to leave, one tenant slipped a note, saying, "She's making me lie for her," according to The Washington Post.

Further investigation turned up a grizzly discovery

After the police received the note, they stalled for a reason to stick around the residence and asked if they could dig in the yard. "We were just digging and digging," one officer said, per the New York Post. "And I could see Dorothea staring out the window at us, above." At first, they found some bones, and then they uncovered a shoe with a foot in it. At that point, they stopped digging, secured the area, and called the coroner's office. Further excavation of the property turned up bodies of unidentified victims. Over the course of a few days, they found seven bodies in various states of decay. In the middle of it all, Puente kept herself emotionless and managed to flee to Los Angeles, where she was captured five days later after a pensioner she tried to befriend recognized her from the news, according to the Los Angeles Times.

When the police found Fink's body, he was wearing only boxer shorts and socks. Court filings (via Casetext) said his body was wrapped in plastic and a bedspread secured by duct tape. Police also said he had absorbent pads placed over his face and between his upper legs. Police found no evidence of any trauma to Fink's body. But when a toxicology report came back, amitriptyline, loxapine, and flurazepam, were found in tissue samples from his brain and liver. The cause of death on the coroner's report was stated as "undetermined."

Puente's trial wasn't a slam dunk

On August 26, 1993, after a dramatic trial that lasted a year, Puente was convicted of three of the murders. Although, after more than three weeks of deliberation, the jury could not agree on the other six, according to the Los Angeles Times. Some jurors believed some of the deceased may have died of natural causes, and the judge declared a mistrial on those charges. The three murder convictions were enough to put Puente in prison for life without the chance for parole. For Benjamin Fink, Puente was found guilty of murder in the first degree.

As for Puente, she died on March 27, 2011 at the age of 82. She maintained her innocence until her death. In one of her final — and rare — interviews as an inmate at Central California Women's Facility in Chowchilla, California, Puente seemed astonished that she hadn't yet been discovered as a modern day miracle worker. "The only time they were in good health was when they stayed at my home. I made them change their clothes every day, take a bath every day, and eat three meals a day," she told Sactown Magazine. "These were people—the Salvation Army wouldn't take them." Without a hint of irony, she added: "When they came to me, they were so sick, they weren't expected to live."

The story of Puente and her victims, including Benjamin Fink, is part of the Netflix's "Worst Roommate Ever." The trailer is on YouTube.