Harald Hardrada: The King Whose Death Ended The Viking Age

Hailing from the cold lands of Scandinavia, the Vikings plied the seas in search of conquest and plunder for over 200 years, leaving an indelible mark on European history, per Britannica. While there is no official "end date" for the Vikings, it is Harald Hardrada, the Burner of Bulgars, the Hammer of Denmark, the Thunderbolt of the North — as he was called by his contemporaries — who was the last Viking king who personified the Viking Age, as Don Hollway, author of "The Last Viking: The True Story of Harald Hardrada," proposes in History Extra.

With his life floridly documented by multiple poets, their verses collated by the 13th-century poet Snorri Sturluson in the epic saga Heimskringla, Harald Hardrada saw battle in his teens, found his fortune in Eastern Europe and Asia Minor, wrote poetry, and pillaged, before eventually ruling over Norway and falling in battle in England in 1066 C.E.

Contemporary historical sources are thin on the ground

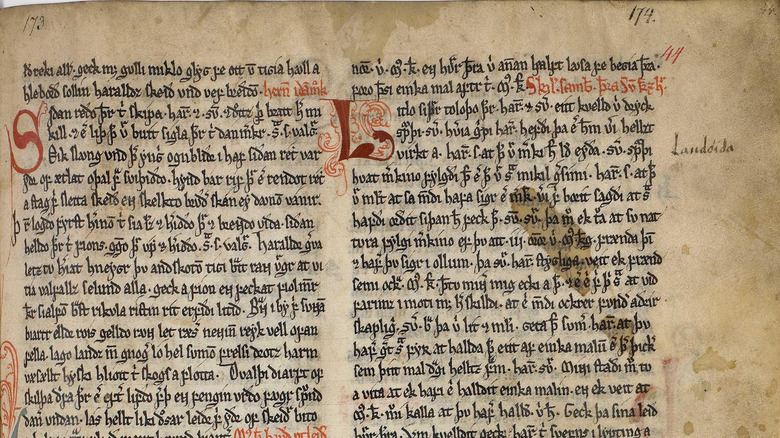

A great deal of information on Harald Hardrada comes from the 13th century Icelandic saga Heimskringla or "Orb of the World," per Britannica. The Heimskringla, containing a section called King Harald's Saga devoted to his exploits, was itself a collection of poetry and oral traditions later compiled by the Icelandic historian and saga-writer Snorri Sturluson, many decades after Harald Hardrada's death in 1066, per Britannica.

The various sagas within the Heimskringla were written by poets or "Skalds," who were often paid by their patrons to write favorable accounts of their lives, such as great feats in battle or their wise leadership, as detailed by the University of Cambridge. One such poet was Tjodolv Arnorsson, an Icelandic Skald and shepherd for Harald Hardrada, as detailed in the Large Norwegian Encyclopedia. From these poems, we have a richly illuminated description of their subject — though with dubious accuracy.

Thanks to his exploits in battle, particularly his last — the 1066 Battle of Stamford Bridge — Harald Hardrada also receives mention in "The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle," as reported in an article by English Heritage, specifically the contemporary Manuscript C of the chronicle, per The British Library.

'Hardrada' is actually a nickname

Harald's apparent last name of Hardrada can be loosely translated from Old Norse to English as "hard ruler," but surprisingly, as G. Turville-Petre of the University of Oxford wrote, "It is not applied to him in any contemporary poetry which we know, nor even in historical prose." It is possible that instead, as John Marsden postulates in "Harald Hardrada: The Warrior's Way," Harald was known as "hárfagri," or "Fair Hair," like his famous ancestor Harald FairHair, the first king of Norway over a century prior, per Britannica.

This epithet of "hard ruler," which was introduced into historical accounts and regal lists well after Harald's reign, was nonetheless well deserved. As Don Hollway, author of "The Last Viking: The True Story of King Harald Hardrada," states in an article on Military History Now, "He lorded over his people with a tyrannical hand ... When England and Scandinavia were moving in a more democratic direction than most of Europe, Harald still ruled in the manner of the bloody-handed kings of yore."

Harald Hardrada fought his first battle aged just 15

According to the Heimskringla, Harald Hardrada fought his first battle at the young age of 15, in the 1030 battle of Stiklestad, alongside his half-brother King Olaf II Haraldson of Norway. Their Danish opponent Cnut the Great defeated them, killing King Olaf (later to become Saint Olaf) and forcing the young and wounded Harald to flee into hiding, per the Viking Ship Museum in Roskilde. Harald found shelter with a peasant in an isolated location, giving him time to recover from his wounds before setting out away from his homelands, for what would become an exile of many years.

After this ignominious start to Harald's saga, as told by the Heimskringla, he was able to regroup with the remainder of Olaf's forces and settle in for the harsh northern winter, before setting sail in the spring for Kyivan Rus (an area that spanned modern Ukraine, Belarus, and Russia, per Britannica). Being well-received by the grand prince of Kyiv, Yaroslav the Wise, Harald and his men were hired as mercenaries and began to build their reputation and strength in numbers.

He began making his fortune in Kyivan Rus, then onto Constantinople

From 1031 C.E. Harald and his fellow warriors had found safety and gainful employment as mercenaries in Kievan Rus, as told in the Heimskringla. With their help, the Grand Prince of Kyiv, Yaroslav the Wise (via Britannica), was able to subdue the "eastern Vindlan men" and the "Lesions," coinciding with the onset of cultural and political primacy of Kyiv in Eastern Europe.

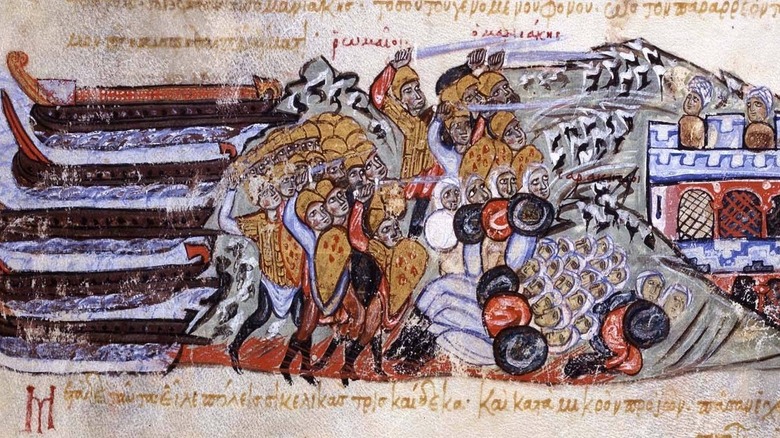

After several years of gaining a reputation as a fierce warrior and formidable leader, at the service of Kyiv, Harald decided to broaden his horizons. Further south lay the city of Constantinople, the heart of the powerful — and very wealthy — Byzantine Empire, per Britannica. Here he sailed, joining the Varangian Guard and embarking on a multitude of military adventures that brought enormous amounts of plunder, which Harald sent to Kyiv for safekeeping.

He was renowned for his cunning in battle

While still ostensibly in the service of the rulers of Constantinople, per Britannica, commanding his Varangian guard alongside the imperial Greek troops, the Heimskringla describes a dubious but compelling series of sieges Harald Hardrada won against increasingly tough castles in Sicily.

Getting off to a flying start, Harald's first bright idea came when faced with an impregnable, well-provisioned castle. With the help of his "bird-catchers," as the Heimskringla describes them, he caught birds that foraged in the woods for food but nested in the castle and turned them into incendiary guided missiles, tying lit splinters of wood to their backs before releasing them. Returning to their nests in the castle's highly flammable roofs, Harald's impromptu air force set the castle ablaze and forced the occupants to surrender.

A second castle in this part of the Heimskringla's saga was tackled from the opposite direction — underneath. While the besieged enemy was distracted by daily attacks, another group of men was directed to dig a tunnel underneath the castle, hidden from view in a nearby deeply bedded stream. Harald's men eventually tunneled far enough underneath that they erupted through the floor of the food hall, full of the inhabitants eating and drinking, whereupon they wreaked havoc and took the castle.

Harald Hardrada used his own version of the Trojan Horse

According to the Heimskringla, when reaching another castle, stronger and tougher than he had faced before, Harald used his guile instead of a direct attack. His men were ordered to act as if they didn't know what to do and instead play games outside the castle — but out of bowshot. After days of this, the defenders relaxed and started leaving the gates open while they watched the games. With their helmets disguised under hats and weapons under cloaks, as soon as the opportunity presented itself his men charged the gates and, after a punishing fight, seized the castle.

Another daunting castle, according to the Heimskringla, required a masterstroke of deception, which Harald delivered — in the shape of a coffin. Spreading rumors about his camp that he was sick, Harald hid in a tent. When his death was announced, his men requested he be buried in the castle. Knowing this would attract wealth, the enemy gladly agreed, and a coffin was borne by Harald's men into the castle. But once inside, the "Trojan coffin" was dropped in the entryway, his men jammed the gates open, and the rest of his army stormed inside, slaughtering everyone and making off with a great deal of plunder.

Harald was not above using deception to get his way

After what was a presumably hard day of marauding around the country, the Heimskringla records that Harald's men decided it was time to pick a good spot to camp for the night. The high ground was the preferred choice, but Gyrger, commander of a different branch of Constantinople's military, claimed the location for his soldiers, telling Harald and his mercenary Varangians to take the lower ground.

Harald refused, essentially saying finders, keepers. A heated confrontation came close to a full-on armed battle before "men of understanding" intervened and persuaded them to cast lots instead.

Harald and Gryger each placed a marked "lot" into a box, to be drawn by a third person. Before the drawing, Harald asked Gryger to show him the mark on his lot, claiming this would prevent them from accidentally making the same mark. The marked lots went into the box, and one was drawn. As the lot drawer held up the winning lot, Harald snatched it from his hand and threw it into the river, exclaiming, "That was our lot!" Gryger pointed out no one had been able to verify the mark on the lot, to which Harald said, "Look at the one remaining in the box — there you see your own mark upon it." Indeed, the remaining lot had Gryger's mark, ensuring through Harald's sleight of hand that he and his men would be sleeping on the higher, drier ground that night.

The ghost of Harald Hardrada's brother, Saint Olaf, helped him escape from prison

The story of Harald Hardrada is intertwined with myth and exaggeration, and in one episode, as told in the Heimskringla, there is an encounter with the supernatural in the form of King Olaf's spirit. Half-brother to Harald, King Olaf had fallen in the battle of Stiklestad against the Danes in 1030 C.E. and was canonized as a saint a year later, per Britannica.

As described by Don Hollway in "The Last Viking: The True Story of King Harald Hardrada," it was during one of Harald's darker periods that he is supposed to have received this ghostly visitation. Charged with debauching a noblewoman, Harald had been imprisoned by the Byzantine emperor Constantine, thrown into the dungeons by his own Varangian Guard.

On his way to prison, the Heimskringla tells how the now sainted King Olaf appeared to Harald, promising assistance. While Harald languished in the prison tower, a "lady of distinction" approached with two servants, ladders, and rope. Saint Olaf had previously cured her of a disease and, in a vision, requested she help Harald escape. Reaching the top of the prison tower with ladders and dropping the rope to the prisoner below, the escape was a success. Harald seemingly wasted no time in returning to his men and leading a revenge attack against the emperor who had imprisoned him.

Harald kidnapped a princess in a swashbuckling escape from Constantinople

According to Sky History, Harald Hardrada had accumulated enormous wealth during his years in Constantinople. Unfortunately for him, as told in the Heimskringla, Harald had also managed to scorn the empress Zoe, was thrown in prison, and attacked the emperor. It was clearly time to leave, but Harald had one more prize he wanted to take with him — Princess Maria.

Harald kidnapped the princess and set sail with her on one of his two ships. But his way was blocked by the harbor's barrier chain. This immense chain was designed to prevent the passage of ships, as described in Don Hollway's book, "The Last Viking: The True Story of King Harald Hardrada." Harald told his rowers to aim for the middle of the chain, where it dipped the lowest, with everyone else ordered to the back of the boats to raise the prow. The first boat to reach the chain slid up and over it, but the second was unsuccessful. As it tipped over the chain, the stress on the boat was too great and it split in two. It is not recorded what happened to those on board the stricken ship, but nonetheless, Harald sailed away into the Black Sea with his remaining galley. But what of the princess Harald had kidnapped? He decided to drop Maria off before leaving for good, with a message for the empress about how little power she had over him.

He survived an assassination attempt

After returning from Kyiv to Scandinavia in 1045 C.E., rich from his exploits in Constantinople, Harald eventually ran into Svein Estrithson in Sweden, as described in Frank McLynn's book, "1066: The Year of the Three Battles." The two formed an alliance against Magnus the Good of Norway, who had repelled Estrithson's advances into his territory and sat squarely where Harald Hardrada intended to eventually be — the throne of Norway.

As the tale told in the Heimskringla goes, after an angry conversation where Harald spoke his mind to Estrithson after his intentions for the alliance were questioned, the latter snuck onto Harald's boat to kill him with an ax. Harald suspected this might happen and had slept elsewhere that night, leaving a wooden log under his blanket instead. The ax Estrithson swung to kill Harald was left stuck in the wood when he fled, proof enough for Harald to convince his men to leave before more treachery befell them, as described in W. Bern Mac Cabe's "A Catholic History of England."

After this brush with death, Harald and his army entered Norway and met with Magnus the Good, where the two relatives reconciled their differences.

He got to work pillaging Scandinavia

As the Heimskringla tells, Harald Hardrada allied himself with Svein Ulfson, nephew of the Swedish King Olaf, on his return from the Eastern empires of Byzantium and Kyivan Rus. Harald was now very wealthy, but for him this was merely a resource to further his ambitions. With Ulfson, Harald put together a "great force" and set sail for Denmark, where they began to pillage the coastal lands. The Heimskringla verses are quite explicit when describing the terror Harald and his army of marauding Vikings visited on their victims: "Harald! thou hast the isle laid waste, / The Seeland men away hast chased, / And the wild wolf by daylight roams / Through their deserted silent homes."

Part of the intent behind these raids was to convince the people of Denmark that King Magnus the Good of Norway was unable to protect them and bring about their submission, before subduing Norway too, as described in an article by Life in Norway. King Magnus' response was first to gather an army together, but it was suggested to him that a diplomatic solution may be more fortuitous, since he and Harald were related, and that Harald was extremely rich. An agreement was struck, according to the Heimskringla, whereby Magnus would share the throne with Harald in return for Harald sharing his wealth. The alliance lasted about a year, ending with Magnus' death in battle in 1047, per Britannica, leaving Harald Hardrada the sole ruler of Norway.

He was a patron of poets and considered himself one

As G. Turville-Petre discussed in "Haraldr The Hard-Ruler And His Poets," the Norse kings prized poetry and elevated their bards to almost royal status. Indeed, Harald Hardrada's predecessor King Olaf brought his poets to the epic battle of Stiklestad, telling them to observe and then write poems of the event — though he may not have intended them to record his defeat and death. As an article by The Department of Anglo-Saxon, Norse and Celtic of the University of Cambridge elaborates, the reputation of Viking kings was inextricably linked to their power and influence, and written manuscripts were not then part of Scandinavian culture. Therefore, their acts of valor, wisdom, and generosity were told by their poets — or skalds — and keeping them well rewarded ensured the tales would be splendid.

A list of poets from 13th century Iceland and whom they served, called the Skaldatal, lists 13 skalds under Harald Hardrada, according to G. Turville-Petre, who suggests there are probably more. One skald, Tjodolv Arnorsson (who also worked as a shepherd for the king, per the Large Norwegian Encyclopedia), documented Harald's military expeditions to Asia Minor and Iraq, as described by Realm of History.

According to the Heimskringla, Harald was not shy about his own poetic abilities, composing 16 songs on his way back to Scandinavia from Constantinople, all dedicated to his future wife Elisiv.

Harald Hardrada died in one of England's most famous battles

From 1016 to 1035 C.E., England was ruled by King Cnut the Great, who also ruled Denmark and Norway, per Britannica. About five years after his death, the throne of England was restored to its old royal line, ending the Viking rule of England. Nonetheless, the kings of Norway and Denmark retained spiritual claims to English soil, and in 1066 C.E. Harald Hardrada led the last attempt by the Vikings to claim the English throne.

The year 1066 C.E. is better known for another English battle, the Battle of Hastings, fought soon after Harald Hardrada's attempt to claim England, per Britannica. Sailing up the River Ouse, in the northeast of England, Harald's fleet of 300-500 ships joined forces with 12 more boats commanded by Tostig, the former earl of Northumbria who had been stripped of his title and banished for his harsh governance by the then-king of England, Harold Godwinson, as the World History Encyclopedia describes. Tostig wanted his earldom back, and Harald was glad to agree. Pillaging as they went, the invading force won a decisive victory near the city of York, before being surprised by the appearance of Harold Godwinson and his army. A pitched battle followed, and the unprepared invaders were defeated, with "The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle" mentioning that only 24 ships returned to Norway.