The Most Powerful Indigenous People In Pre-Colonized Mexico

Numerous Indigenous tribes inhabited Mesoamerica before the Spanish colonization, and some of them connected to and established bigger empires. Mayas, Olmecs, Zapotecs, Chichimecas, and others resided in warm tropical areas, similar in the principles they built their cultures on, but still different in language, ethnicity, and belief (via Mexico: a country study).

The Aztecs managed to join many different tribes and ethnicities into one great empire, the Aztec Empire. By intentionally colonizing smaller communities and gathering financial taxes, they urbanized the valley of central Mexico and formed a society established on class division and war. According to World History, the Aztecs frequently battled, for land, honor, or as a form of ritual, and a big part of their mythology was connected to warfare.

While the tourists flock to see the fascinating remains of the great Aztec Empire scattered around Mexico city, the descendants of the once-great civilization still live in the country today. Subjected to continuous, systematic racism (per Discrimination against Indigenous Peoples in Mexico), they continue to protect their culture and languages — there are 68 Indigenous language groups in the country, which are combined out of 364 linguistic variants.

Here is the story of the most powerful Indigenous tribe in pre-colonized Mexico explained.

The origin of the Aztecs is still unknown

Archaeological excavations confirmed the presence of humans in Mexico as early as 10,000 B.C., with many different civilizations residing in the area throughout history (via Mexico: a country study). Maya, Toltec, Zapotec, and Mixtec people thrived in the local jungles of Central America. The Valley of Mexico in central Mexico was an especially abundant place, full of fertile soil and water, but also a meeting place of different cultures. Some of these tribes settled in the region, often battling for dominance. The Mexica tribe was the last to join the party, but they were also the most persistent — later known as the Aztecs, these communities might come from northwest Mexico (in present Sonora and northern Sinaloa state), but this is only speculation.

The Aztecs had their own version of how they got to central Mexico. Following the god of war Huitzilopochtli and his sound signals from Aztlán, a mythic place up north, they embarked on a journey. They explored the area and got involved in a few conflicts, when finally, in the 1300s, they settled on Lago de Texcoco, an area where Mexico City stands today. They didn't choose this place by chance, but only after seeing the sign — a cactus holding an eagle holding a snake in its beak.

The Triple Alliance made the Aztecs the most powerful in the region

After the Aztecs established Tenochtitlán, the city that soon became the center of the empire, their society became much more complex. The community split, separating peasants, who worked in the farms, and the elite, living in courts. Much more focus was put on the military, slowly forming agreements with neighboring areas, as per Mexico: a country study. The Triple Alliance was formed between city-states Tenochtitlán, Texcoco, and Tlacopán, and its massive military power was capable of gathering around 17,000 soldiers in an hour.

The alliance established certain rules, practicing royal marriages and other political connections throughout the empire. They divided their areas into neighborhoods, promoting urban planning and organization. By establishing a financial system of taxation, the empire was flourishing from various materials and products, developing into a powerful market force.

Different tribes — Mexica/Aztec, Acolhua, and Tepaneca — gathered to form the alliance (per ThoughtCo). Together, they could continue to spread their power across the basin, overthrowing leaders and overtaking city-states. But they didn't work as one, as each of three had their own part of the valley that they controlled, and they shared profits from taxation in unequal parts, with Tlacopán gaining the least. While Tenochtitlán became a military power, Texcoco was more developed in terms of construction, engineering, law, and art.

After they conquered, they collected taxes

The Aztecs had different ways of financing their empire, but one of the main reasons for its expansion was to extract tribute from conquered people. They colonized not only to spread their influence but also to get more communities supporting their causes. According to Jamail Center for Legal Research, the Aztecs developed an intricate legal system that implemented taxation and tributes. There were different rules for different people, and many laws were similar to current legislation.

Only citizens of the Triple Alliance paid taxes, and those who didn't comply had to face enslavement and loss of property. Nobility, priests, disabled or homeless people, and children were excused. Because the Aztecs didn't use money, they collected taxes in products, crops, and other materials. Sometimes they used feathers, pieces of gold, and cacao beans.

For communities that were colonized later and weren't a part of the Triple Alliance empire, the law was to pay tributes. These contributions were collected every once in a while, mostly in 80-day, 6-month, or 12-month periods. The officials who collected tributes were called calpixques, and while expected tributes weren't outrageously high, the punishment in the case of avoidance was harsh.

The Aztecs loved war

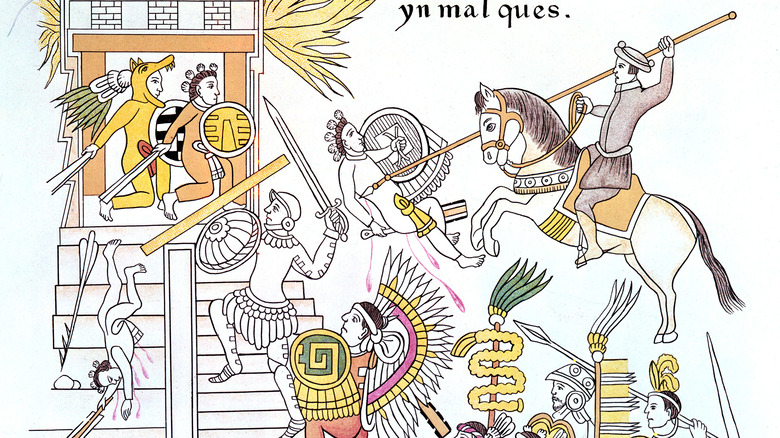

War is the one thing the Aztecs are known after — as ruthless warriors, they often attacked neighbors and other territories to expand their empire. But they had strict rules around warfare, mostly following a certain procedure (via Jamail Center for Legal Research). Several crimes were worthy of war, such as killing an Aztec ambassador or merchant, unpaid tributes, or unwillingness to do business with the empire. When war was declared, the attacked community had 20 days to accept Aztec domination, but they were also gifted weapons to fight with. Three rounds of offers like this were possible, and if the attacked community still hadn't responded, the Aztecs invaded the region. Many of the captured warriors were used during human sacrifice rituals.

When the Aztecs went into battle, they were organized into ranks (via World History). Led by the king and the war council, warriors had different titles according to their position. Two elite warrior groups, the eagle warriors and the jaguar warriors, were known to be the most courageous. They wore the most spectacular wear, too, battling dressed in jaguar skins and feathered suits, topped with beaked and fanged helmets. When all warriors gathered, the Aztec army could count over 200,000 men, with the addition of scouts (who went first) and priests dressed as the god Huitzilopochtli. They used various dangerous weapons, like the macuahuitl, a sword covered in obsidian blades and spears. They also used tools to throw darts and javelins, attacking their enemies from a distance.

'Flowery wars' were a thing

The Aztecs firmly incorporated war into their mythology, believing that human blood feeds the god of sun and war, their protector Huitzilopochtli. For that reason, they treated battles as a kind of ceremony for which one needs to be properly prepared. They also practiced human sacrifices, and for that reason, they needed captives. Indeed, dying in battle or on the sacrificial stone was a special kind of honor for the members of the Aztec Empire.

As explained by World History, sometimes these battles were staged and didn't evolve from a serious conflict. The only reason for them was to capture warriors, who were later sacrificed to Huitzilopochtli. They called these wars "xochiyaoyotl," or "flowery wars," for one sad reason — the captured and killed warriors, dressed in colorful feather battle suits, looked like dead flowers when taken to Tenochtitlán after battle. Many of these flowery wars took place in the eastern part of the empire in the cities of Atlixco, Huexotzinco, and Cholula. Some of these conflicts, like the flowery war in Chalca, didn't go as planned and evolved into a real dispute.

The city of Tenochtitlan became the center of the area

The valley in central Mexico, where the Aztecs built Tenochtitlán, was covered in water at the time when the Aztec civilization peaked. Between A.D. 1300 and 1500, the artificial island on the lake Texcoco gave space to the most powerful city in the area (via Live Science). Tenochtitlán soon became a place where the Aztec elite resided, alongside high priests, warriors, and others. The Aztecs developed similar urbanistic solutions as some other great civilizations did, as they had straight and wide roads but also canals to access areas directly with canoes. They even built an aqueduct to supply citizens with fresh water.

One of the most important features of the city was the Templo Mayor, the sacred area in the middle of the city also named the Sacred Precinct (per The Metropolitan Museum of Art). These premises included around 70 buildings hidden behind a massive wall and embellished with portraits of snakes, which were sacred animals in the Aztec culture. The most fascinating part of Templo Mayor was its two pyramids, which symbolized sacred mountains and rose to almost 90 feet. The left one was built in the honor of god Tlaloc, portraying the Hill of Sustenance, while the right one stood in the name of Huitzilopochtli, portraying the Hill of Coatepec. The Aztecs used the sacred quarters and both temples for different ceremonies and celebrations, including the most important human sacrifices, which took place on special occasions.

Sometimes, the Aztecs ate humans

There is still a lot to uncover regarding the Aztec cannibalism, as many of the speculations from the past were actually proven wrong. Most of the sources about cannibalism came from Spanish conquistadors, who described in their diaries every detail of their quests, but sometimes these details were very subjective. Bernal Díaz del Castillo described how Emperor Moctezuma and his close companions ate young boys' meat, while Francisco López de Gómara reported on a wall of skulls, protecting the inner temples in Tenochtitlán. But it turned out Gómara wasn't wrong, as his claims were confirmed in 2017 when archaeologists unearthed the wall (via Mexico Daily Post). They did find human skulls, and some of them belonged to women and children. Some researchers claim that the Aztecs' cannibalistic past was intentionally omitted to hide the fact that the Spanish conquistadores actually did civilization a favor by removing the aggressive Emperor Montezuma. By freeing them of his brutal reign, some argue that a Mexican country was born.

Other academics, such as Stephanie Zink, argue that there is still a lack of information about the Aztec cannibalism — the only thing confirmed is the civilization did practice human sacrifices (around 20,000 per year). There are several theories about cannibalism, but mostly they are unsupported by evidence, as the most reliable proof are the Aztec codices written by the actual Aztecs, not their conquerors or later visitors.

They attacked their enemies with sound

The Aztecs had different ways to scare the enemies away, including their fascinating battle suits that allowed them to imitate the animals of the jungle. One of the most inventive methods was the use of death whistles, small clay instruments that resembled a human skull. These whistles produced the creepiest of all sounds, characterized by the archaeologists as the screech of death itself. While the whistles were found in different locations around Central America, it took scientists years to actually blow them and discover their purpose, as per Daily Science Journal.

One example of such a whistle was found in Tlatelolco, next to the skeleton of a young man who was missing a skull. The grave was located at the bottom of the temple of god Ehecatl. Ehecatl dominated the realms of wind and rain, so some believe the whistles were honoring the wind-loving god. Others believe they were created to celebrate gods of death like Mictlantecuhtli since the sound gives the impression of someone dying.

The whistles were made so that the air traveling through the tool is dispersed in different opposing directions, making a sound that echoes a human scream. It is still unknown why these instruments were used, but there are several theories. One suggests they were used in battles to scare opponents, while another claims they were a means of sound therapy for the Aztecs themselves to promote relaxation. Since many of these death whistles were found in graves, some researchers believe the victims of human sacrifices used them to connect with the spirits before they joined them in the underworld (via Gizmodo).

The biggest threat to the Aztecs were Spanish colonists

The Spanish conquistadores, arriving from Europe looking for new lands to colonize, firstly discovered Mesoamerican civilizations in 1517 during expeditions led by Diego Velazquez (via World History). They did mention the stone pyramids and golden objects and even met some Indigenous people, but they didn't connect the dots just yet. Only after another exploration — this time led by Hernán Cortés — was the existence of the Aztec Empire confirmed.

Cortés, traveling with 11 ships and 600 men, landed on Mexican soil in Potonchan in the Tabasco region, where he immediately started to make connections with the locals. The language barrier was an obvious problem until a slave girl from the Malintzin tribe was given to the Spaniards as a gift. She spoke several languages, the local Maya language, but also the Nahuatl, spoken by the Aztecs. Soon, the colonists were able to communicate with the people they encountered, which came in handy when they met the great Aztec emperor Montezuma. The latter chose diplomacy and greeted his foreign guests with grace, gifting them with splendid objects. The truce didn't last long, as Montezuma was held hostage only two weeks later, while the Spaniards dishonored the sacred precinct by installing crucifixes over the temples. With the help of rebellious tribes from the Aztec Empire itself, Cortés first took over Tenochtitlán in 1520. Overpowering the neighboring cities around the valley, the Spaniards sieged the area until the final collapse in 1521.

The Aztecs reportedly didn't believe the Spaniards were gods

Many facts and details about the fall of the Aztec Empire were altered by the Spaniards themselves in an attempt to glorify their victory and portray themselves in a better light. One of the fabrications, which is still widely accepted by the general public, is the story of why the Aztecs were really overpowered. According to Francisco López de Gómara, the retired Cortés' secretary who never visited Mexico at all, the Aztec people believed that the Spaniards were returning gods, descending from the sky; specifically, the feathered Aztec god Quetzalcoatl, who was celebrated on a specific day. Cortés and his men did arrive on that specific day, and the Aztec masses, drenched in religious ecstasy, allegedly mistook them for god (via JSTOR Daily).

But the reality behind this "mistake" is much graver — fabrication and its continuous endorsement is a clear sign of "political pornography," as stated by historian Camilla Townsend (via JSTOR Daily), another layer of colonialist ideology, always justifying its crimes. By associating technological progress with moral superiority, it perpetuates the prevailing narrative of conquest. It is true the Aztecs were overpowered by better equipment and different weapons, but also by the sight of horses — which were animals they had never seen before — and ships. The Spanish conquistadores also battled with diseases they brought with them on ships, killing the local population faster than fire. The inner conflict in the empire also made a big contribution, as several tribes resisted Montezuma by joining forces with Cortés.

Mexico City is built on the ruins of Tenochtitlán

After the Spaniards took over Tenochtitlán, they started to build the new city, calling it Mexico City (via History). It soon became the most powerful city in North and South America. Indigenous people were banned from the region through special work permits they needed to enter the area, but the colonizing white race still mixed with the Indigenous blood, creating a new class of Mestizo people. The society was deeply divided and racist, firmly separating various Indigenous people from Mestizos, Criollos (Spanish descendants born in colonies), and Europeans. Until the 18th century, the political power over the city resided in the hands of Spanish aristocrats who were born in Spain. After that, the Criollo people took over and demanded independence,

Visitors who stopover in Mexico City today can still see the greatness of the ancient Aztec ruins. A stone's throw away from the city center, one can walk down the path of the timeworn Avenue of the Dead, just as the ancient Aztecs did. One can still see the two pyramid temples, the Temple of the Sun and the Temple of the Moon. In the city center, next to the great cathedral (allegedly built with the stones from the nearby temple), the outlines of Templo Mayor can be traced on the ground (via The Culture Trip). But the real treasures can be found in the Museo Nacional de Antropologia, including Aztec gold and the Cuauhxicalli Eagle Bowl, a massive stone calendar that weighs around 25 tonnes.