The Lost Ancient Plant Which Gave Us The Heart Symbol

Heart symbols are everywhere. They're so ubiquitous in our world that they transcend language and cultural barriers, carrying meanings of love and romance. It's because a heart symbol is technically a kind of ideogram, defined by Merriam-Webster as a symbol that represents an idea but not a particular word or phrase for it. As everyone knows, including a heart emoji in a text message can add a lot of meaning, but it's not exactly something that can be spoken out loud.

Part of the reason the heart shape is such a well known symbol is that it has a surprisingly long history. People have been using heart shapes for thousands of years. An article by Art And Object discusses the history of the heart symbol and its earliest known appearance, as a heart-shaped pendant from an ancient civilization who once lived in the Indus Valley in South Asia. The pendant, made from gold and ceramic, is kept at the National Museum of New Delhi.

The romantic meaning carried by the heart symbol likely also has botanical origins. The plant it came from, once grown around the ancient city of Cyrene in North Africa, is long extinct and surrounded by mystery. A plant so valued that the Ancient Greeks put pictures of it on their money, and Julius Caesar kept a huge personal stash of it in Rome. That plant was known as silphium and, as the Deccan Chronicle explains, in the ancient world, silphium became as valuable as gold.

The History of Hearts

According to National Geographic, the Harappans were one of the world's first human civilizations, and as such were some of the first to use heart shapes. A paper in the Journal of Mosaic Research explains that these early heart shapes were based on the leaves of the pipal tree (Ficus religiosa) and were used abundantly as decoration. However, there's nothing to suggest the Harappans attached any romantic meaning to the shape. Another plant that may have influenced the heart shape is English ivy, as mentioned by BBC Arts. What's more, according to The Joy Of Plants, ivy has two very old associations: It represents fidelity, because of how tightly it clings to whatever it's attached to, and its evergreen leaves have symbolized immortality since the ancient Egyptians, who dedicated it to Osiris, the god of life and death.

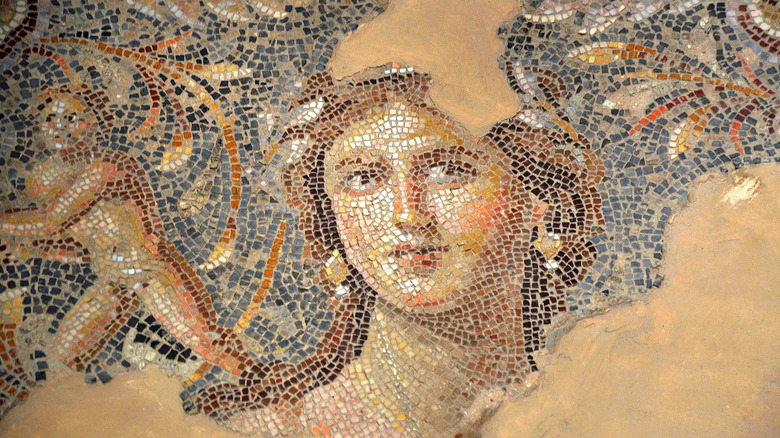

The most explicit link between the heart shape and romance, however, came from silphium, and the shape came not from its leaves but its seeds. As Kew Gardens explains, silphium once grew in North Africa and, for its many uses, it became exceptionally important to cultures all around the ancient Mediterranean. Among other things, the Greeks and Romans prized it as both a contraceptive and an aphrodisiac. Silphium was so valued that the ancient city of Cyrene, where it was grown, became one of the wealthiest on the south coast of the Mediterranean sea. Until the plant went extinct and was lost to the world. No one is entirely sure why.

Roman Birth Control

Ancient authors wrote often about silphium and evidently considered it an effective means of birth control. National Geographic discusses how silphium may have been a big reason why, even during peaceful times, the Roman population remained stable, or even decreased. To the Romans, silphium was used in much the same way morning after pills are today. Considering how infamously promiscuous the ancient Romans were, it's little wonder they placed such value on the plant.

The Celator attributes this piece of old wisdom to the ancient Greek physician Soranus of Ephesus, who wrote an early textbook on reproductive health called the Gynaeciorum. As well as its use in contraception, Pliny the Elder recommended taking silphium with wine to help regulate menstrual cycles.

While some people have been doubtful of these ancient ideas, there may be some truth to Soranus' claims. Even though silphium is extinct, it's related to several species of giant fennel that still grow wild in Africa and Asia today. These plants produce a compound called ferujol, and there's some evidence this can prevent pregnancy. Wild carrots are another related species, able to block progesterone production, which is why they've long been used in folk medicine as an herbal contraceptive. In other words, there's plenty of support for the idea that silphium was just as effective as the ancients believed it to be.

Ancient Mediterranean Medicine

As well as being a contraceptive, silphium was considered useful as a medicine for numerous other things, though it's not easy to say if it would have been effective for these other uses. The Roman naturalist Pliny the Elder wrote extensively about silphium in volume 4 of his book, "Naturalis Historia." He describes several remedies that use the silphium plant itself, and many more using the plant's resin, known as laserpitium or (amusingly) laser. According to Pliny, silphium could shoot down a variety of ailments, including fevers, headaches, respiratory problems, and digestive complaints. One noteworthy use Pliny mentions for silphium seems to be to help recovery following a miscarriage, suggesting that even among ancient apothecaries, it was still important in reproductive health.

Pliny writes about silphium in two more volumes of his "Naturalis Historia," including, in volume 3, a horticultural use for silphium as a medication for trees. The strange thing about all of this is, while Pliny knew so many of its uses, the silphium plant was already extinct by the time he wrote about it. He even mentions this himself, saying that "the silphium of Cyrenæ no longer exists." After Pliny, the Romans had been forced to use a related plant, asafoetida. The Romans imported this from the Middle East, and it still grows in Iran today. Pliny refers to it as "the silphium that comes from Persis," but he also makes a point of saying how asafoetida is "much inferior to that of Cyrenaica."

For the Love of the Romans

The Ancient Romans' love of silphium really can't be overstated. They absolutely adored it. As a paper published by the Bulletin de l'Académie Nationale de Médecine notes Pliny the Elder considered it "one of the most precious gifts of Nature to humanity." There's even surviving Roman poetry that mentions it. The poet Gaius Valerius Catullus was a flamboyant romantic, and he wrote often about his lover, a woman called Lesbia.

In a collection of his works, "The Carmina of Caius Valerius Catullus," several are written for her. One particular poem refers directly to silphium. Ancient Literature gives a translation in modern English. Comparing the number of her kisses to the amount of sand in Libya, Catullus writes "You ask how many kissings of you/Lesbia, are for me and more than enough/As great as the number of the Libyan sand/that lies on silphium-bearing Cyrene.

An old paper in The American Journal of Philology analyses this and suggests that Catullus is referring to silphium as a heart medicine, to treat his nervous instability. But with silphium widely used as a contraceptive, it's a safe bet that Catullus had more carnal implications in mind.

The City of Cyrene

Cyrene was founded by the ancient Greeks around 630 B.C.E. According to Oxford Research Encyclopedias, it was the major Greek city in Africa, giving its name to the entire region around it, known as Cyrenaica. Its ruins, with their echoes of forgotten grandeur, can still be visited in modern day Libya, near the town of Shahat.

Pliny the Elder talks about the silphium trade in volume 1 of his "Naturalis Historia," saying how Cyrene traded extensively with Greece and Egypt, as well as exporting huge amounts to Italy to use in perfumery. The ancient Greek geographer Strabo also mentions Cyrene in his book, "Geographica," saying how, at the height of its power, Cyrene was an independent city state. The city was surrounded by vast stretches of fertile soil, much of which produced nothing but silphium. Being so vital to the Cyrenese economy, attackers once targeted these silphium fields instead of the city, to cut off its source of wealth. Strabo notes that silphium was nearly lost because of this attack.

As such an important trade hub, Cyrene became a significant cultural landmark of the ancient world. Several ancient celebrities had a connection to the place. The poet Callimachus was born there, and the writer Plautus set one of his plays there. Particularly interesting though were philosophers like Carneades and Aristippus. They belonged to the Cyrenaic school of philosophy, which, appropriately enough, was all about a hedonistic approach to life and finding the pleasure of the moment.

The Plant that Refused to be Farmed

An obvious question is why, if silphium was so beloved by the ancient world, it was only grown in Cyrene. The reason, apparently, is that it simply couldn't be cultivated anywhere else. BBC Future elaborates on this puzzle, explaining how the Greek philosopher Theophrastus, still known as the father of botany, studied silphium personally but was unable to solve the problem. Silphium simply refused to be farmed.

It's still a mystery why the Greeks were unable to cultivate silphium, but modern botanists have some ideas. A recent example of another, similarly inflexible plant is the huckleberry. The state fruit of Idaho, huckleberries have a variety of culinary uses, but they've never been successfully farmed –- and not for any lack of trying in the early 20th century. Huckleberry bushes grown from seed simply don't produce fruit, and wild plants are difficult to transfer because of their sprawling root systems and long underground stems. As a result, huckleberries can still only be picked from wild plants growing in their natural habitat. Seemingly, silphium was just as stubborn.

There's some support for silphium being similar to huckleberries given in an article published in the journal Conservation Biology. It notes that Aristotle once wrote about how "cultivated silphium is not as potent as wild silphium." This suggests that, much like huckleberries in the 20th century, even when silphium could be grown elsewhere, it still refused to give its growers what they wanted.

Silver Coins, Silver Hearts

Silphium was so important to the economy of Cyrene that the plant was depicted on the silver coins the Cyrenese used for trade. An article, "The Coins And The Cult," in Penn Museum's expedition magazine, shows a few of the coins minted by what was, at the time, possibly the wealthiest city in all of Africa. While some coins showed only an image of the plant, many featured stylized representations of heart-shaped seeds. The seed eventually became iconic of the plant itself, with some coins bearing only a simple heart shape, like the one featured on the cover of a 1995 issue of The Celator.

These silver coins from Cyrene may have been what made the connection in people's minds between heart shapes and passionate romance. Economic Botany suggests this may have been deliberate, as a form of ancient marketing. The paper argues that, while ancient authors didn't tend to mention silphium's use as an aphrodisiac, the people of Cyrene may have spread this idea more subtly, using the seemingly phallic imagery of the silphium plant on their coins. Whether or not this is true, the heart shapes on Cyrenese coins would have certainly popularized their association with carnal desires.

An Ancient Cooking Ingredient

Strangely for a plant so heavily used for sex and medicine, silphium was also a popular food around the ancient Mediterranean. According to the book, "The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks," silphium was a common household ingredient in ancient Greek kitchens, alongside familiar modern ingredients like sesame, coriander, and mustard. Silphium, though, was an expensive delicacy, being only available imported from Cyrene. Surviving ancient artwork shows Cyrenese silphium merchants weighing their wares with a huge set of scales.

The book, "Cooking in Ancient Civilizations," describes a simple everyday meal that the Romans would have enjoyed -– a porridge made from barley and chickpeas, which used silphium as a seasoning. The recipe dates back to the famous Roman gourmet Marcus Gavius Apicius, whose ancient writings still exist today. His cookbook contains numerous recipes that use silphium as an ingredient, as well as its resin, laser. It's used in several dishes involving melons, cucumbers, and gourds (translated as pumpkins), and is also an ingredient in stews, meatballs, roasted meats, and a few sauces. As well as foods though, Apicius uses silphium in a recipe for a digestive aid, called Oxygarum. Even as a cooking ingredient, silphium's medicinal properties were still important.

While silphium may be gone, South Asian cuisine still uses asafoetida as a seasoning, particularly in India and Iran. Adventurous chefs can use this as a substitute for silphium and try out some actual Roman recipes.

The Extinction of Silphium

Sometime around the first century C.E., silphium went extinct, and the exact reasons why are still being debated by historians and archaeologists. According to National Geographic, the world's last stalk of silphium was presented to the Roman Emperor Nero. The Bibliothèque Nationale de France suggests that this may have been the first plant extinction caused by humans and, even if not, an article in Conservation Biology confirms that it's the first plant extinction recorded by the history books.

Silphium may have gone extinct, at least in part, because of over-harvesting. Kew Gardens explains that, while the Greeks were careful to avoid gathering too much at once, the Romans showed no such restraint. Another factor may have been desertification, as North Africa has been steadily growing drier over the centuries. Ongoing habitat loss could easily have led to the Romans harvesting more of the plant than could grow back.

Following silphium's extinction, the Romans turned to asafoetida instead, a similar plant that still grows wild in Iran. This was Pliny the Elder's "silphium that comes from Persis," but it came with an unfortunate downside. Where silphium was often described as fragrant and was used to make perfumes, asafoetida smells vile. Its name literally translates as "stinking resin." In the kitchen, the smell rapidly vanishes when asafoetida is cooked but, with its offensive odor, it's hard to imagine asafoetida being quite so popular in the bedroom.

No One's Sure What Silphium Was

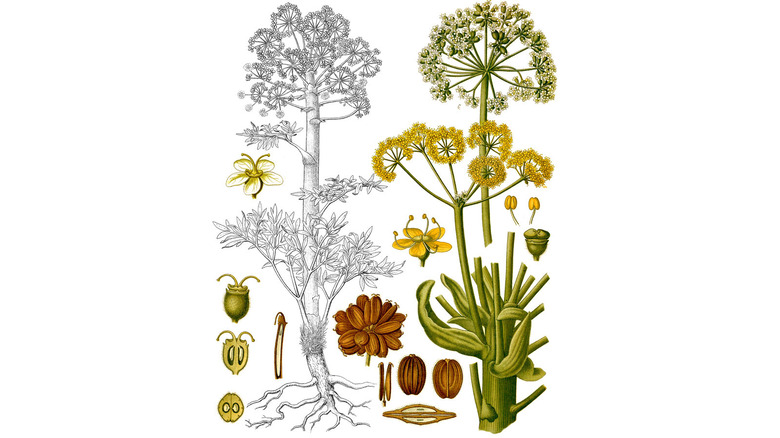

Both botanists and historians have puzzled over the true identity of silphium. Being extinct, it's hard for anyone to be certain, but there are a few clues. As Kew Gardens explains, even in ancient times, the Greek botanist Theophrastus likened it to the ferula genus of plants. Ferulas are also known as giant fennels, which still grow abundantly in North Africa, and certainly do bear a resemblance to the images on old coins from Cyrene. Some researchers have suggested that silphium could be common giant fennel (Ferula communis) or Tangier giant fennel (Ferula tingitana) –- the latter being the better candidate with the closest resemblance to ancient silphium, according to a paper published in the Bulletin de l'Académie Nationale de Médecine.

The most exciting development in this story comes recently, in a study published in the journal Plants in 2021, which identified a previously unknown plant species. Ferula drudeana is the most promising candidate for ancient silphium found so far. Growing in rural Anatolia, F. drudeana has a fragrant gum resin with spice-like qualities and medicinal properties. It may have been carried there by smugglers who collected seeds from Cyrene in the long-forgotten past.

Perhaps the precious silphium plant isn't so extinct after all. If this is true, then all efforts need to be made to protect the species from habitat loss and even possible commercial exploitation. Silphium already cheated death twice. It may not be so lucky the third time around.