What Flirting Was Really Like In The Victorian Era

It's often thought that those living in the Victorian era suffered from a massive case of prudishness. There are stories about covering furniture legs, lest the sight of a table ankle excite some admittedly weird lust, and rumors that the mere mention of anything even slightly R-rated was completely off the table. But how true is that?

Not very, says Dr. Holly Furneaux and The British Library. Furneaux calls these ideas little more than stereotypes, and while things were definitely done differently in the 19th century, the idea that entire generations of people went around never thinking about their fellow Victorians in that warm and fuzzy way just isn't true. On the contrary, the Victorian era was a time when sex was actually being studied in a scientific way: sexology was a scientific field, desires were being analyzed, and even words we still use today — like heterosexual and nymphomaniac — were coined. Not exactly prudish, right?

That's not to say the sexual landscape of the Victorian era wasn't different than it is in the 21st century. Take flirting. Letting someone know you were interested in them as more than just a friend was done in a variety of different ways, and a lot of the proper ways of flirting weren't just complicated, but pretty audacious. Want everyone to know your business? In the Victorian era, it's likely they would have.

What incredible artistic talent you have!

If having a portrait done just so it can be printed on some calling cards and handed out to everyone you visit sounds like a very Victorian thing to do, it was. According to the BBC, it was in the 1860s that these cards — called cartes de visite — became incredibly popular. Many people would keep them in scrapbooks, but others would cut them up and paste them on painted pages, to create Monty Python-esque collages.

It's a craft that hasn't been well documented, mostly because collages weren't meant for public display, and were simply sort of a neat thing to show friends after dinner. That was actually pretty important, and having a book of witty, charming collages meant a lady was a good and proper host. It gave what was described as "social currency," and while a lot of the details of the importance of these collages have been lost, it's thought they were a great excuse to sit down with a potential partner, get close, look through a book, and share some intimate laughs.

And many times, those images would have a definite meaning. In addition to being a not-so-humble brag about whose images were there and who was in your social circle, some of the images could be pretty risque. It was deemed a "safe way" to flirt: Collages could be as intriguing or suggestive as they were carefully crafted to be, and it was a craft where women created a precise message to share.

Want to chat with my dead Grandma?

Today, the Ouija board is the stuff of horror movies and skepticism — even though the Smithsonian says that the game might actually give an insight into something even more fascinating than the spirit world: the human subconscious.

When the Ouija board first hit the market, it was a roaring success. Demand was so high that by 1892, there were seven U.S. factories churning out the boards, and while part of that demand was from people looking to contact dead relatives and solve murder mysteries, it was also the centerpiece of some domestic bliss. Norman Rockwell even painted a Saturday Evening Post cover that showed a 1920s-era couple getting cozy over a Ouija board (pictured).

The Atlantic says that it was pretty perfect for any Victorian-era couple who wanted a reason to get close. Those playing with a Ouija board were originally instructed to place the board on someone's lap, sit with their knees touching, and place their fingers together on the appropriately heart-shaped planchette. It wasn't just great for a little snuggle time, but it was perfectly acceptable. They were just playing a game, after all ... the intimate setting just happened to be a bonus.

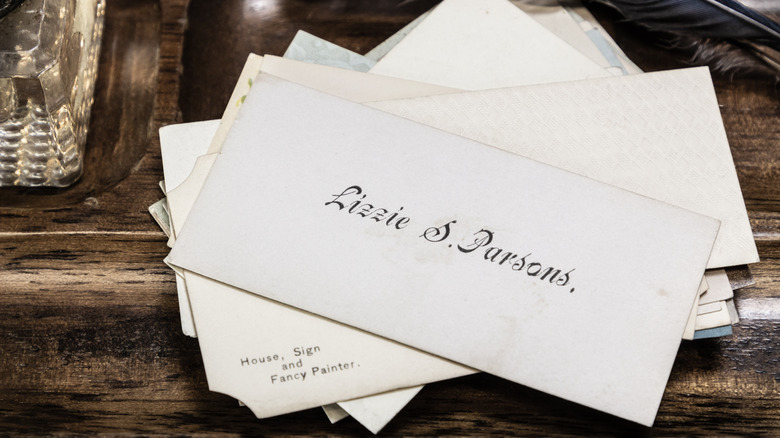

Here's my card

The idea of a calling card — a simple sort of business card with a name on it, along with perhaps a handwritten message on the back — became wildly popular first in France and then in the U.K., starting in the 18th century. Having a silver tray piled high with calling cards was, says Hoban Cards, sort of a 19th century Facebook friends' list. An offshoot of these wildly popular cards were escort cards, and National Geographic says that they conveyed a slightly different message than straightforward calling cards. That was anything from the relatively innocent "May I.C.U. Home?" to the less innocent "Not Married and Out for A Good Time."

Cards offered all different kinds of messages, and the idea was that anywhere couples might mingle was a good place to slip the object of your affection a card. Some had poems, riddles, or pictures on them, and historians are pretty sure they weren't meant to be taken completely seriously. They were meant to kick-start a conversation, be good for a laugh, and keep communication on the down-low.

Interestingly, historians have found cards of all sorts: In addition to those that men would give women and women would give men, there are a few examples of flirty cards that women could give another woman. While they're obviously not sure, that seems to suggest that these secret communications were used when chaperones needed to be ditched, and judgmental third parties needed to be avoided.

Putting it all on display during The Season

Debutante balls are precisely the sort of thing that, depending on a person's point of view, might seem like the worst thing in the world, or just the bee's knees. According to The Association for Consumer Research, the idea of presenting all upper-class, eligible women who have recently come of age to their peers started back with Queen Elizabeth I. It remained popular for a surprising amount of time, and these coming-of-age events got a bit of a makeover with Queen Victoria. She's the one that added the white dresses and introduced the curtsey, but still, the point of the event remained the same: To announce a girl's eligibility to receive suitors.

Typically done for only the crustiest of the upper crust, Tatler says it was the sort of event that saw wealthy families moving the household from country estates to London properties, where they could attend the balls of "The Season," and then make sure their newly-introduced daughters could easily make appearances around all the eligible bachelors.

The London Season says that yes, it was an entire season of presentations, flirtations, and hope of landing a serious suitor. After girls were publicly presented — usually in midwinter — they spent the following six months at all of the dances, sporting events, and cocktail parties a person could stomach. It was all done while keeping their eye on the prize: A man.

What are you reading?

According to the University of Delaware's British Literature blog, the Victorian era saw a massive jump in literacy rates. While the start of Queen Victoria's reign saw only about 60% of men and less than 50% of women able to read and write, that had jumped to about 90% for both men and women by the 1870s. It's not entirely surprising that books were used to flirt with, but what is surprising? It was wildly complicated.

Atlas Obscura says that it was what a person did with a book that conveyed a message to any suitor who happened to be watching, and instructions on how to send these messages were often printed on small cards called flirtations. As detailed in one card, holding a book in both hands was a way of asking someone if they were willing to be escorted home, while resting the book on the right cheek was a message that someone was being too bold. Left cheek? That was a warning that people were watching, while touching the book to the right shoulder was answering in the affirmative. Left shoulder? That was a hard pass.

Other cards have been found giving similar instructions for using things like pencils and handkerchiefs, and if this all sounds complicated, it was. That's led to a discussion about how widespread these secret communications were, and simply put? No one's quite sure.

Fans aflutter

Hand-held fans might not be popular today, but in the 18th century, they were an incredibly important part of the way a woman presented herself. That, says The National Trust, is largely because most women didn't have the luxury of speaking freely in most places, so when they wanted to put forward a certain elegance or express things like a simple "yes," or "no," they relied on using gestures from their fans.

That definitely happened ... right? This is super interesting, because according to Sotheby's historians, fan messages — like dropping it to communicate that someone was being friend-zoned — were first documented in writing in an 1827 pamphlet. And yes, there's a "but."

Fans had been popular during the French Revolution, but after so many fan-wielding women had gotten their heads lopped off, popularity understandably decreased. Duvelleroy, the creator of the fan language pamphlet, had a very good reason to want fans to come back into style: They were a retailer of fine fans who had moved to London post-French Revolution. That means it's kind of unclear just how widespread the practice was. There certainly were cards detailing just how to have a conversation via fan, it's mentioned in contemporary works of fiction — from writers like Oscar Wilde — and it's a case where it'd be better to err on the side of caution. In other words, don't touch that fan handle to lips unless really, really interested in a big, long smooch.

Everyone wanted a Valentine ... almost

Valentine's Day in the Victorian era was a time to express interest in that particular person that makes your heart go all aflutter, and according to Skidmore College professor Catherine J. Golden (via VictoriaWeb), there was a new trend that was all the rage: Sending Valentine's Day cards. In 1840, the UK's postal system introduced the Uniform Penny Postage, making it easy to send a valentine for just a penny. Although the idea of sweetly-worded cards had been around for centuries, the advent of the Penny Post made it much more popular, and in 1841, the post office found themselves deluged with around 400,000 valentines sent to and fro across England.

Most of these valentines were handmade, and usually featured all the familiar imagery of hearts, flowers, chubby babies with wings, and church spires. They often conveyed serious intentions: A valentine with a red rose declared love, while that church spire? That hinted at wedding bells and a lifetime of loyalty.

Not everyone wanted the kind of valentines that were being sent, though. The Smithsonian says the Victorians were also sending so-called "vinegar valentines," which ranged from slightly funny (featuring, for example, a man kissing a donkey) to outright cruel. Some ridiculed people for drinking habits, for their profession, being too demanding, and some? Some even implored the recipient to take their own life. Some reports say that suicide did, in fact, happen, making these cruel cards a precursor to social media trolling — sometimes, with the same impact.

The secret language of stamps

Stamps might not seem like the most romantic thing in the world, but according to The Philatelic Database, the Victorian era saw the development of a "language of stamps."

At the time, there were no real guidelines on how to put a stamp onto an envelope, and the postal standards of today were developed in response to the public's use of a stamp language. Stamps placed in different positions at different angles meant different things — for example, a stamp placed vertically but upside-down could mean that the sender wasn't free to engage in a love affair, while the same upside-down stamp tilted to the left could indicate that the sender was pretty thrilled with the prospect of a romantic partnership.

The devil was, as they say, in the details. The Postal Museum says that there were no universally accepted guidelines for what stamps meant, and getting a clear message across meant both parties needed to use the same code. A bit of a challenge, perhaps, but who doesn't love a secret message?

A rose by any other name?

Receiving a bouquet of flowers was about much more than just some home décor in the Victorian era, as looking at the color and type of flower included in the bouquet could allow the recipient to decode some secret messages.

Author and historian Vanessa Diffenbaugh says (via Antique Trader) that in researching her book "The Language of Flowers," she found that flowers were used to send all kinds of messages. Where does flirting come in? Sending someone, say, some pink roses would indicate that they've kind of got a crush on the person, but it may or may not be too serious. Red roses, on the other hand, were a declaration of true love. Add in some red tulips, carnations, and dahlias, and that's the kind of message that brings up fanciful dreams of a life happily ever after.

The idea of a romantic bouquet of red roses has held on into the 21st century, but there were other flirty flowers, too. Apple blossoms were sent by a suitor testing the waters to see if the object of his affections would be interested in exploring the possibility of a relationship (and she could send back a yellow carnation for "no," and — weirdly — some straw for "yes,) while other flowers — like white lilies, daisies, and myrtle — were also used to indicate varying degrees of infatuation.

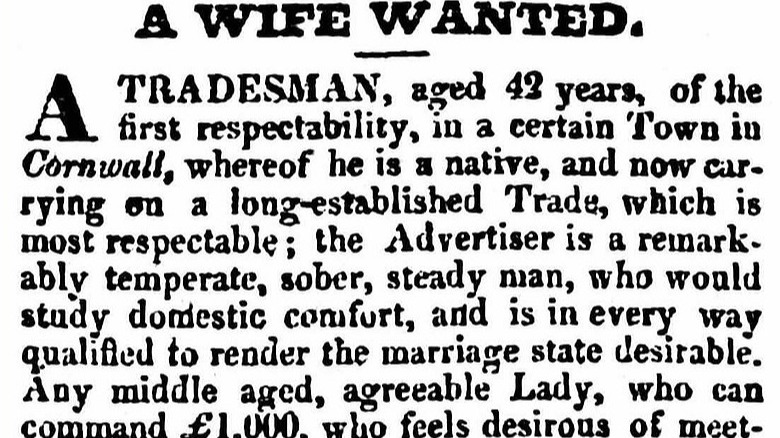

Swipe left or right? Before there was Tinder...

While there's a lot to be said for a long, romantic courtship filled with flowers and secret messages, not everyone had time for all that nonsense. Some people just cut right to the heart of the matter and took out a lonely hearts' ad detailing exactly what they were looking for in a prospective partner.

The Post Magazine says that the very first practical Romeo to do that took out an ad in 1695, and the idea steadily gained traction as advertisements became more affordable and papers increased in circulation. By the time the Victorian era rolled around, there were entire publications dedicated to being nothing but a place where men and women could advertise and search for potential partners, and the whole thing reached a high point in 1900. (Once rumors started circulating that the ads were actually placed by people looking to lure women into slavery or trafficking situations, the popularity started to dwindle, but never went away completely.)

Ads could be almost hilariously straightforward, like one 1866 ad re-published by Find my Past. The hopeful suitor wrote that he was looking for someone who was "more of the fine woman than the pretty one, good teeth, soft lips, sweet breath ... rather inclined to fair than brown, ... her bosom full, plump, firm, and white, a good understanding without being a wit." It also adds that anyone under 14 years of age need not apply ... they were different times.

Thanks, but no thanks

Not all flirtatious advances are wanted, so what did the proper Victorian lady do when she wanted to dissuade a suitor? Letter-writing was a big deal in the 19th century. Victoriana says that there were scores of templates for letters that could be personalized and sent along to reject a suitor's advances, and these templates could be found in almost any book on etiquette. Interestingly, many would-be suitors hoping for specifics on why they were being refused were destined to be disappointed, as most abided by the idea that a true lady "never explains or complains."

That said, many were pretty straightforward. One from The Ladies' and Gentleman's Model Letter-Writer suggests a response of just a few lines that simply says: "...deeply as I feel honored by your preference — reasons which I am not at liberty to explain, prevent my entertaining a thought of a more intimate acquaintance."

Some did get into details as to why they were refusing. Some templates allowed the writer to fill in reasons for their "unchangeable dislike" of said suitor, while others gave more of a "too late, that ship has sailed" vibe. Another legit reason was, as one letter explained, "I ... suspect ... motives not the most honorable have induced you to play the lover to a woman sufficiently old enough to be your mother." The writer continues, "I hope I have said enough to make you ashamed of your conduct," and it just goes to show that people haven't really changed all that much.