The Untold Truth Of The Green Berets

The Special Forces are one of the most revered fighting units in the United States Army. Known for the distinctive Green Berets they wear, the Special Forces are often considered some of the best trained units in the entire Army. Some of their exploits are incredibly famous, including their vast contributions to the Vietnam, Afghanistan, and Iraq wars. But equally important are their lesser-known escapades that haven't been splashed across the front pages of mainstream newspapers.

The Green Berets first came to widespread prominence during the Vietnam War, notes HistoryNet, when their daring adventures were televised and shown to American audiences on the nightly news.

Dozens of Hollywood movies have been made featuring Green Berets as main characters, including "Apocalypse Now" and "Black Hawk Down" (via Business Insider). Throughout their history, Special Forces have been involved in assassinations, covert operations, and all kinds of secret missions, some of them known to the public but many more are buried far away from the light of day.

This is the untold truth of the Green Berets.

The first U.S. Special Forces unit was formed in 1942 with Canadians

Contrary to popular belief, the first U.S. Special Forces unit was formed during World War II in 1942. Most scholarly works place the Special Forces' birth in 1952, but from 1942-1945 there was actually an early Special Forces unit within the Army. According to the U.S. Army Center for Military History, on July 9, 1942, the 1st Special Forces Regiment (SFR) was activated at Fort William Henry Harrison in Montana. The regiment was a joint Canadian-American unit, and it existed for two-and-a-half years until it was deactivated in January 1945. The 1st SFR participated in campaigns on the Aleutian islands, Italy, southern France, and Germany.

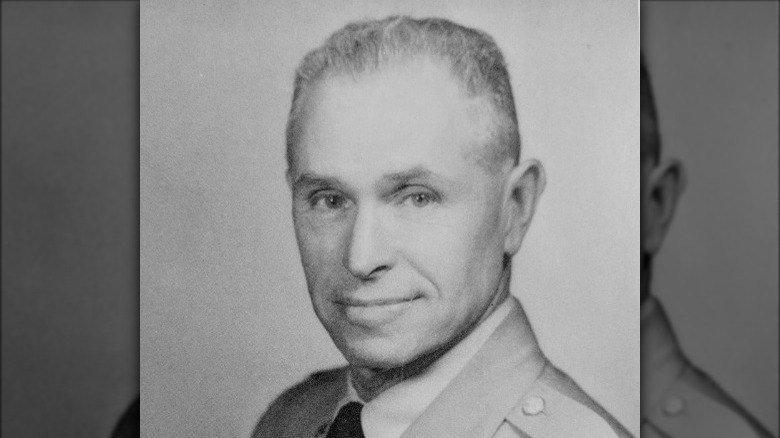

Seven-and-a-half years later, on June 19, 1952, at Fort Bragg, North Carolina, the 10th Special Forces Group (SFG) was activated under the command of Col. Aaron Bank (per the U.S. Army's Special Operations Command). The 10th SFG grew to 1,700 members by 1953, and later that year the first units deployed to Germany in Bavaria. At the same time, units also went to Korea to train North Korean partisans to fight against their former country. The 10th SFG was popular among former WWII veterans and especially previous officers of the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), a WWII era espionage and counterintelligence agency and precursor to the CIA.

Wearing Green Berets was banned in the 1950s

Nowadays, the Special Forces and green berets are synonymous, but there was actually a time in the late 1950s when they were banned from wearing the distinctive headgear. The U.S. Army's official website states the headgear's history in the U.S. Army actually goes as far back as WWII, when OSS agents used to wear berets during their time in France. Many of these OSS officers carried over the tradition when they joined the 10th SFG, and by 1954 the green beret had become their unofficial headwear with soldiers wearing them publicly starting the following year. However, in 1957, a commander at Fort Bragg banned the wearing of headgear, and it disappeared from the Special Forces uniform, officially and unofficially.

Yet, in 1961, Special Forces Brig. Gen. William Yarborough wore a green beret to meet the newly inaugurated President John Kennedy (per John Prados in "Safe for Democracy"). The president was supportive of the headgear, and in April 1962 he called the berets "a symbol of excellence, a badge of courage, a mark of distinction in the fight for freedom." The berets became the official headgear of the Special Forces from then on, and it continues to be today. They are a source of pride in the Special Forces, and the soldiers wear them as recognition of their elite status.

The Green Berets actually have six stated missions

It might sound surprising, but the Green Berets have six separate stated doctrinal missions that make up their role. According to the U.S. Army website, the six missions are counterinsurgency, unconventional warfare, direct action, foreign internal defense, special reconnaissance, and security force assistance. Through these missions, the Special Forces achieve a variety of important goals, and they are on the front lines against terrorism abroad. Their missions are geared to "seize, capture, recover, or destroy enemy material or recover personnel with quick strikes."

In addition, one of the proudest legacies of the Green Berets is their history training the militaries and armed forces of friendly allied nations. They still continue to do so, and three of their six missions explicitly deal with this role. The Green Berets have long specialized in guerilla warfare, and that continues to be a part of their missions today. According to the website, Special Forces soldiers take on extremely sensitive and highly technical missions, including infiltrating enemy lines and sabotaging enemy channels of communication and supplies. They focus on "small-team operations" and use the most current and cutting edge technology, weapons, and gear.

The Green Berets are their own distinct group within the Army

In the media and Hollywood there is often a tendency to lump the Green Berets and all elite U.S. military units together as Special Forces, but this is incorrect. As stated on the U.S. Army website, the Green Berets refer specifically to the U.S. Army Special Forces and their groups. Other elite U.S. military units, like the Navy SEALs, Army Rangers, Marine Raider Regiment, and Air Force Special Operations Wing, collectively form part of the Special Operations Forces (SOF), a group distinct from the Green Beret Special Forces. The Green Berets are also a part of SOF but as individual units within the overall command.

Currently, there are Special Forces groups located in several areas of the U.S., including Fort Bragg, North Carolina; Fort Campbell, Kentucky; Fort Carson, Colorado; and Fort Lewis, Washington. In addition, the National Guard has their own Special Forces groups and subordinate units spread throughout 21 states. Another important but not often highlighted aspect of the Special Forces are the support soldiers who are mission critical to the needs of the Special Forces.

The first official Special Forces missions took place behind the Iron Curtain

According to the State Department, President Harry Truman explicitly recognized that the subversive acts by the USSR were undermining the U.S. and its Western allies. So he put a directive in place to provide covert operations as supplemental support for national security activities abroad. As part of this supplement, the 10th Special Forces Group (SFG) was sent to Bad Tölz, Bavaria, Germany. According to Annie Jacobsen's 2019 book on secret operations, "Surprise, Kill, Vanish," the group was named the 10th group to fool the USSR into thinking there were 10 units of Special Forces troops active instead of one.

The 10th SFG's initial tasks in Bad Tölz were modeled on those of the famous OSS Jedburgh teams, who dropped into France during WWII and armed partisan armies against the Nazis. The 10th SFG teams had to be capable of secretly infiltrating and exfiltrating targets through a variety of means, and soldiers had to be fluent in a foreign language and have extensive survival skills. Their job was to work operations behind Soviet lines as a contingency for a Soviet invasion of Western Europe. SFG recruits had to undergo a rigorous training program to officially join the Special Forces, and they prided themselves on being "hard-bitten troopers who were willing to take calculated risks and face challenges that conventional units need never be concerned with," as noted by Col. Aaron Bank, the group's first commander.

They almost lost a nuclear weapon in the 1960s

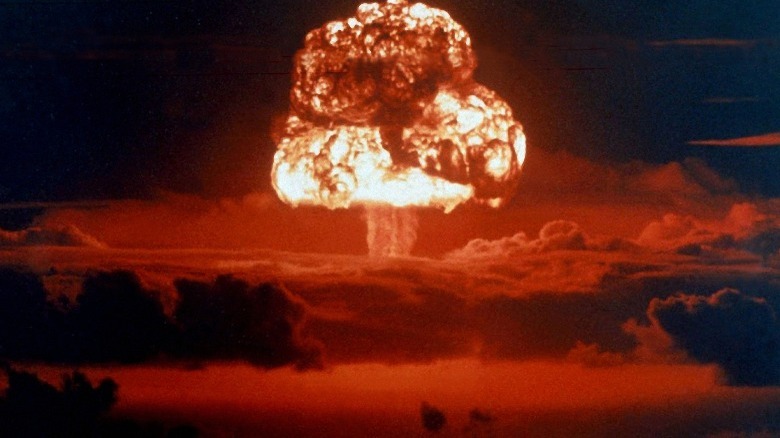

In one of the most ambitious and daring programs, starting in the late 1950s the U.S. Army conceived the little known Project Greenlight. In her book, "Surprise, Kill, Vanish," Annie Jacobsen explains that the goal of Greenlight was to give Special Forces teams a portable nuclear weapon that they could carry behind enemy lines and detonate. The teams carried W54 Special Atomic Demolition Munitions, or SADMs, that weighed nearly 100 pounds each and had a payload nearly half of that of the bomb that was dropped over Hiroshima in 1945. Jacobsen detailed one training mission gone awry in Okinawa, when a Greenlight crew actually lost a nuclear device for a brief period of time. The bomb slipped out of its harness, and the U.S. Navy had to come find it later.

In his autobiography, "Code Name: Copperhead," ex-Special Forces Sgt. Maj. Joe R. Garner claims he was part of an early Greenlight team training at Fort Bragg in 1958. Garner was a newly trained Special Forces soldier, and he participated in an experimental mission that involved him parachuting out of an airplane with a nuclear weapon strapped to him in a rucksack. He was not informed that an atomic bomb was supposedly in his rucksack — he just thought it was a conventional bomb — and he claims he found out years later it was actually a nuclear weapon that was strapped to him.

The CIA initially ran Green Berets during Vietnam

Though the Green Berets are under U.S. Army command, in their first years of deployment to Vietnam the CIA actually ran most of the Green Berets' operations. In the late 1940s and early 1950s, presidents Harry S. Truman and Dwight D. Eisenhower gave the CIA the responsibility and authority to conduct covert and guerilla warfare operations through a series of National Security Council (NSC) directives (per the State Department). Due to the nature of Special Forces operations, the CIA took control of the Green Berets when they first arrived in Vietnam in November 1961.

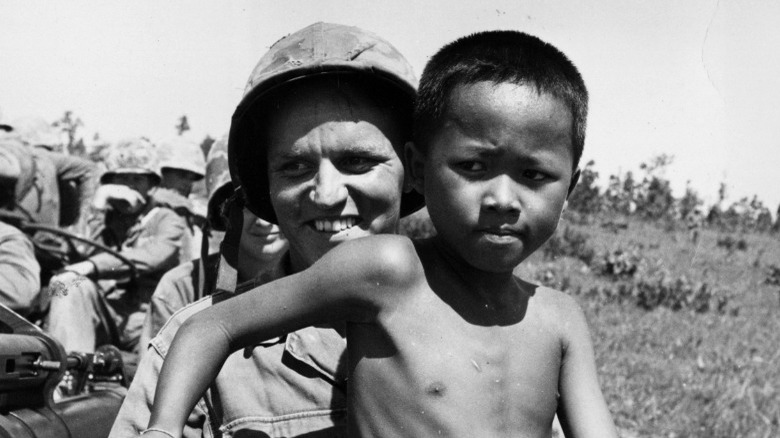

Andrew Krepinevich's "The Army in Vietnam" states the CIA was running a program known as the Civilian Irregular Defense Groups (CIDGs) in Vietnam in the early 1960s. It focused on unconventional warfare operations aimed at pacifying South Vietnamese villages from the infiltrating Viet Cong soldiers. When the Special Forces soldiers arrived, they immediately joined the CIDGs in the villages. They started working with Vietnamese villagers, helping them strengthen their hamlets and creating a "strike force" among the men.

However, Krepinevich argues the Army quickly started to have concerns about the CIA's handling of the Special Forces, and in July of 1962 it was agreed the Army would once again control the Special Forces operations. The Army's rationale was that the Green Berets' role in the CIDGs had become too militarized and could no longer be considered covert.

Their secret Laotian training programs were unorganized

In one of the earliest instances of training armed forces for friendly militaries, Special Forces detachments secretly worked with the Royal Laotian Army to combat to North Vietnamese-led Pathet Lao. It was called Operation White Star and began in late 1959. In "Surprise, Kill, Vanish," Annie Jacobsen writes that the Green Berets were initially disguised as land surveyors working with the National Geodetic Survey, and they wore civilian clothing and carried Defense Department cards identifying them as civilians. The Special Forces commanders considered the Laotians poorly commanded and incompetent in most cases. They noted commanders would drunkenly drive around Mercedes-Benz cars, and they claimed "the concept of discipline or physical training did not exist" among the Laotians.

In 2013, ex-Special Forces Col. Alfred H. Paddock Jr wrote in "Small War Journal" that various Special Forces groups worked with the Laotian army advising them on "weapons, communications, demolitions, intelligence, and operations specialties." Paddock too complains the Laotian units he worked with were poorly commanded, his by an alcoholic Laotian colonel who had a penchant for firing guns and playing with grenades. He also noted Laotians blew themselves up 15 separate times while trying to plant mines during his brief stay. During his time in Laos, Paddock came into contact with Vang Pao, a Laotian general who would work with the CIA continuously until the 1970s.

Did the CIA authorize a Special Forces murder?

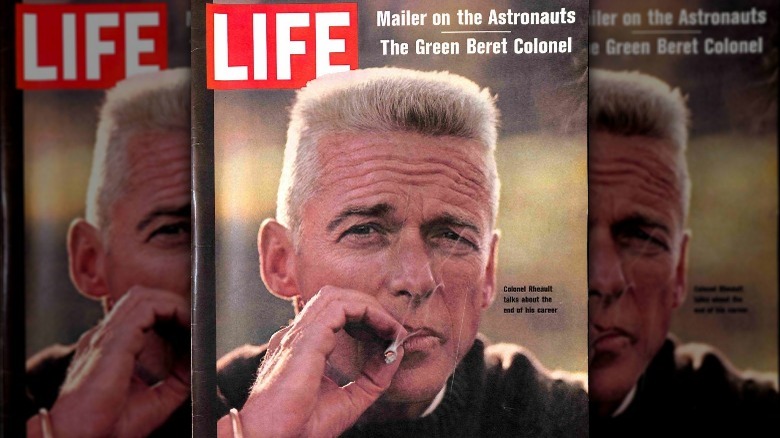

In one of the darkest scandals in Special Forces history, the Green Beret Affair of 1969 lives in infamy in U.S. Army history. The affair centered around the murder of an alleged spy, Thai Mac Chuyen, who had supposedly infiltrated the South Vietnamese Special Forces for the Viet Cong. In an interview with the New York Times in 1971, ex-Green Beret Robert F. Marasco detailed the grisly affair.

Marasco stated that Chuyen had been discovered as a secret double agent when "a raid on a Vietcong camp turned up a photograph of him with a high‐ranking North Vietnamese official." A group of Berets forced Chuyen to out himself through the use of a truth serum. After his confession, in late June 1969, they drugged him with morphine and loaded him onto a motorboat, where they shot him in the head and dumped his weighted-down body in the South China Sea near Nha Trang. Marasco said the CIA had given him a verbal order to murder Chuyen and claimed that even by a conservative estimate there had been hundreds more similar executions.

On August 6, 1969, a Special Forces colonel and seven other Green Berets were charged with premeditated murder as well as conspiracy to commit murder (per History). However, in late September, the New York Times reported the Army dropped all charges against all of the Green Berets after the CIA refused to cooperate with their investigation.

Green Berets rescued POWs behind enemy lines

In one of their most successful missions in Vietnam, Special Forces were principally involved in Operation Bright Light, secret missions behind North Vietnamese lines to rescue American POWs. In his book, "SOG: The Secret Wars of America's Commandos in Vietnam," John Plaster argues the Bright Light missions were particularly dangerous for Special Forces. North Vietnamese (NVA) soldiers would wear clothing from captured American pilots and shoot flares into the air to trick Americans into attempting a rescue mission. Once the helicopter got close, NVA units could effectively fire rockets from short range. Operation Bright Light took place not just in Northern Vietnam but also in Laos and Cambodia, too.

In "Safe for Democracy," John Prados detailed a raid that occurred close to Hanoi in November 1970. According to Prados, the raid went off without a hitch as Special Forces successfully hit a complex near the town of Son Tay, but there was only one problem — there were no prisoners to be found. In a 1995 article for Air Force Magazine, Air Force Col. Carroll V. Glines claimed the raid had involved months of planning and was largely seen as a disappointment by many. However, news reached the POWs in Hanoi (pictured above) of the botched raid, when one of the captive's wives sent him a microfilm of a New York Times article detailing the raid, smuggled inside a piece of candy.

Special Forces operators may have unknowingly helped smuggle drugs

One of the most enduring legacies of the Vietnam War was the rampant drug use among American GIs in the country. Heroin, in particular, was a huge problem for the U.S. Army. According to Sankar Sen in a 1991 issue of The Police Journal, one reason for this was the proximity of their deployment to major drug processing centers throughout Indochina. In an area known as the Golden Triangle, covering parts of Thailand, Laos, and Myanmar, opium has long been a cash crop for local tribes looking to survive. As part of their duties working with tribesmen in the field, Special Forces soldiers often came into contact with opium smugglers.

In his book, "Code Name: Copperhead," ex-Special Forces Sgt. Maj. Joe R. Garner describes how the U.S. affiliated Royal Laotian Gen. Vang Pao was "up to his neck" in the opium trade "along with our CIA." In an even more shocking incident, Garner described a Special Forces team that stumbled upon a "large bundle filled with smaller packages wrapped in Chinese newspaper" while doing reconnaissance. They radioed in the report and immediately were met by multiple unmarked helicopters who promptly confiscated the bundle and flew away. Later, Garner learned the bundle was full of approximately $5 million worth of raw opium, and he claimed it was taken straight to Saigon and "divvied up between U.S. and South Vietnamese 'officials.'" The Special Forces had just unwittingly delivered raw opium to drug distributors.

Green Berets participated in the 2020 Las Vegas Mint 400 Race

While they are known for their military exploits abroad, the Green Berets still find time to participate in events stateside. One example was the 2020 Las Vegas Mint 400 Race, where a Special Forces team participated alongside civilians in the famous race. According to Millitary.com, in March 2020 the 5th Special Forces Group (Airborne) took part in the event in an effort to hone their training — they weren't looking to win.

During the event, the Green Berets completed two 100-mile laps along the grueling course, but they spent much of their time helping stuck and stranded motorists. They pulled out many vehicles from sand pits and towed disabled vehicles back to their starting pits. The Special Forces team used the same equipment, a ground mobility vehicle, as they use in the field and were completely loaded up with M2 .50 caliber machine guns.

Green Berets have to invade a fictional country as part of their training

The Green Berets are legendary for their training regimens, and just making it into the Special Forces is an incredibly grueling task. According to the U.S. Army website, all potential Special Forces soldiers have to take the Special Forces Assessment and Selection (SFAS) course located near Fort Bragg, North Carolina. The course is tough, and about 60% of all candidates fail.

The Army recruitment website details even more of the qualifications for becoming a Special Forces soldier. All candidates have to qualify for the prestigious Airborne or Ranger schools and also have to be able to gain top secret security clearance. The first step towards becoming a Green Beret is a six-week physical fitness and land navigation skill course, which is followed by the SFAS course, and the last step is the Special Forces Qualification Course, a year long program that teaches survival and evasion skills. Finally, after all the training programs are completed, Special Forces candidates participate in a mock invasion of a fictional country named Pineland. This is the final area where soldiers showcase their guerilla warfare skills to see if they qualify to become official Special Forces soldiers.