The Autopsy Of Julius Caesar Explained

The story of Julius Caesar is a strange thing, as the version that many people are familiar with was written centuries after his actual reign and assassination. When Shakespeare wrote the play that's been performed countless times and read in countless schools, he was writing against the backdrop of potential political upheaval: Queen Elizabeth I didn't have an heir, and the potential of another devastating civil war was looming.

It was an all-too-familiar scenario that had played out before, with disastrous consequences. Michigan State University English professor Jyotsna G. Singh says (via The Conversation) that even by the time Shakespeare was writing, there was no general consensus on whether or not Caesar's assassination could be justified in any way. Was he a tyrant who needed to be removed from power? Or were his assassins simply that — assassins looking to increase their own power and clout?

There are a lot of myths about Julius Caesar, including the one about him being born by cesarean section, but there is one seemingly bizarre story that's true — he was the subject of the first recorded autopsy in history. Let's take a look at this story, along with what it might tell us about whether or not Shakespeare got it right and what really happened on those ill-fated Ides of March. Can it tell us something new, more than 2,000 years later? Maybe!

Let's start with why the Senate thought he had it coming

It's worth taking a look at a bit of history behind Julius Caesar's assassination because that history plays into the motives of those who finally took matters into their own hands.

According to History, Caesar was kind of thrown into the middle of a losing battle from the beginning. The Roman republic was struggling to keep itself afloat, and after almost 500 years, the ship was already sinking. Caesar stepped up with some important incentives that were meant to not only shore up the leaks but also cement his place at the top. The problem came when he started passing on input from the Senate on major changes, and that didn't sit well with a group of very powerful people who saw Caesar on his ivory and gold throne, being bestowed titles like "dictator for life."

But here's the thing: Cornell history professor Barry Strauss says (via Vox) that the idea that the assassins were patriots who wanted to return Rome to the powerful republic it had been wasn't the whole truth. "I think politicians don't have a firewall between ideals and practical benefits," he said. "They think what's good for the country is also good for themselves. The senators who joined the conspiracy against Caesar can sincerely say he was a threat to the republic and to them and their way of life."

The big problem? Caesar no longer allowed the military to freely plunder their conquests.

How it all went down

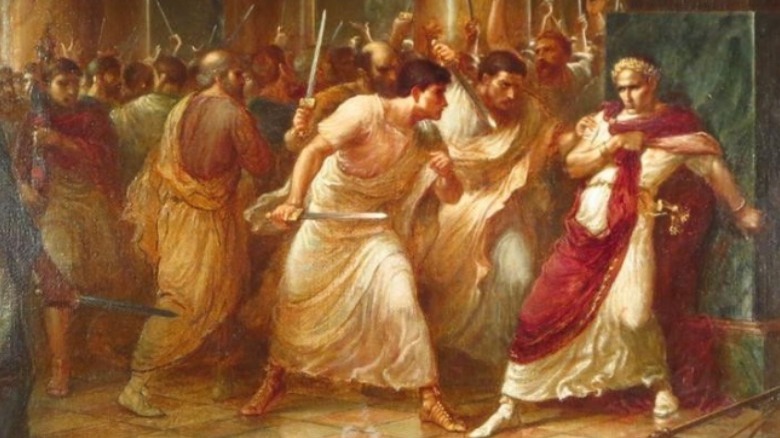

Sure, Julius Caesar was stabbed a whole bunch of times on March 15, 44 B.C., but what really happened that day?

Cornell history professor Barry Strauss says (via Vox) that it really started not with Brutus — that's an idea we get from Shakespeare — but with a man who had his name misspelled by the Bard: Decimus Junius Brutus Albinus. It was actually Decimus who was a trusted companion and friend to Caesar, who had dinner with him the night before his assassination, and who helped convince him that everything was absolutely fine and he should definitely just go about his business like normal.

So, Caesar did. He went into the Portico of Pompey — a Senate house dominated by the statue of his frenemy, Pompey the Great — and took his usual seat on his throne. It wasn't long before one conspirator — named Cimber — approached, then grabbed Caesar's toga. World History says that it was Casca who struck the first blow, and Strauss says the assassins were likely carrying daggers. The history professor also claims that some were tasked with preventing escape or interference from outside the group while others did the actual killing. In front of about 200 senators and countless aides, slaves, and secretaries, Caesar was killed in what was less of a "noble" fight and more of a bloody, dirty struggle. He did fight back, stabbing at least one of his attackers in return — but ultimately pulled his toga over his face and succumbed to the multiple stab wounds.

Zeal quickly turned to, 'Well ... now what?'

According to World History, Julius Caesar's assassins were so preoccupied with planning on taking him out that they really didn't get past planning the actual killing. They didn't have a solid plan for dealing with anything from the power vacuum to the reaction of the Roman people, and if that seems like a massive oversight, it was.

As Cornell history professor Barry Strauss explained to Vox, although the assassins had recruited the help of gladiators to help protect them from Caesar's loyal military, they had been woefully unprepared for the political consequences of what happened next. Immediately, that was a decent amount of chaos. In 2003, Colonel Luciano Garofano — an expert in forensic investigation and forensic medicine — took a look at reviewing what we knew about Caesar's assassination and what conclusions could be drawn from a perspective of our modern medicine. He noted (via Forensic-Psych) that even as chaos descended on Rome, Caesar's body lay in the Senate house for around three hours before it was picked up by servants. By the time he was carried home, word had spread, and people crowded into the streets, crying for their fallen leader.

The findings of the autopsy

Julius Caesar's body was only examined by a doctor once he was returned to his home — and according to History Collection, this is where things get a little confusing. The physician's name was recorded as Antistius, and it's unclear whether or not he was Caesar's personal doctor. He did, however, document all 23 stab wounds and concluded that only one of the wounds had been fatal.

Interestingly, the Institute of Forensic Medicine says that the idea of mortal wounds was already one that was incredibly familiar to the era's doctors. It wasn't entirely surprising, then, that Antistius' findings were reported in Suetonius De Vita Caesarum's biography of Caesar: "Of so many wounds, none turned out to be mortal, in the opinion of the physician Antistius, except the second one in the breast."

The wound in question was one that entered below his left shoulder blade, and there are a few ways it could have killed him. The angle of the stab wound described by Antistius could have punctured his heart, but it's also possible that it perforated his lung instead. In that case, his lungs would have collapsed, and his chest cavity would have filled with blood, killing him. There's also a third option: it may have severed an artery.

Ultimately, the cause of death was extreme blood loss. Interestingly, that also means Caesar had time for last words: Not "Et tu, Brute," as Shakespeare recorded, but (via World History), "You, too, my child?"

The presentation in the forum

The study and documentation of Julius Caesar's body was the first autopsy performed in recorded history (via History Collection). It was important for another reason, too: It gave the name to the entire field of forensic science and the idea of studying what's left in death to get a better idea of what had happened at the end of life.

Antistius didn't just record his findings — he reported them in a very public presentation. According to an article published in Research and Reports in Forensic Medical Science, the physician's presentation on Caesar's 23 stab wounds and his determination that it was a single thrust that killed him was conducted in the public forum. "Forensic," they say, comes from the Latin for "from the forum," which is "forensis," and has come to be connected with precisely what Antistius was doing: creating a snapshot of exactly what had happened when one of the most famous — or infamous — Roman rulers in history was assassinated by his own Senate.

Parallels to the modern mafia

When forensic investigator Luciano Garofano took another look at the original autopsy in 2003, he made some pretty wild observations (via Forensic-Psych). As one of the top criminal investigators and lecturers of his own era, he had plenty of experience to draw from, and for him, the assassination reminded him of something much more modern.

Antistius' original autopsy noted that most of the wounds were concentrated in two areas: Caesar's face and groin (via History Collection). The message of emasculation is pretty clear, but it was the wounds to the face that Garofano was particularly interested in — especially considering that at least one of the slashes came after Caesar had already fallen and was clearly dying.

"That's a favorite Sicilian trick, disfiguring a man's looks," Garofano explained. The multiple assassins each taking a turn had parallels in the modern mafia, too: "Psychologically, it's important for all the conspirators to bloody their hands." Garofano's work draws other comparisons between modern mafia families and the high-ranking, powerful senators of Rome's past. He stresses that they share an unflinching loyalty to the heads of their families, despise weakness, constantly strive for more power, and take the uncompromising view that violence is a completely legitimate option for reaching their end goals.

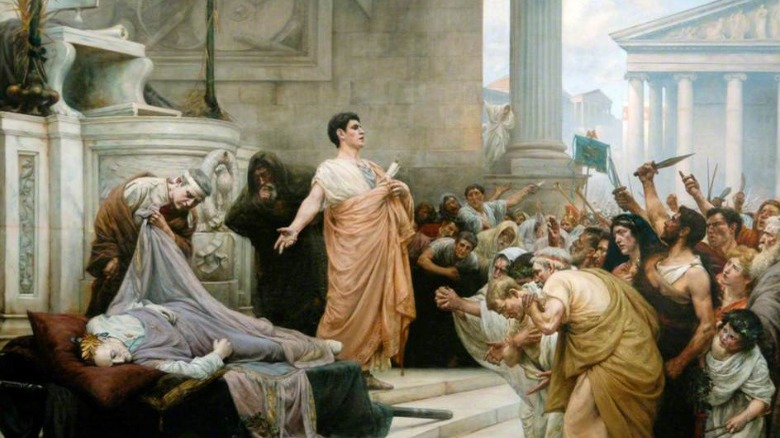

The 23 wounds were documented in effigy

Contemporary historians recording the days and weeks after Julius Caesar's death say that while there were some who wanted him thrown in the Tiber River before all his legislation was undone in an attempt to turn back the clock a bit, it was Mark Antony who stepped in and prevented the entire thing for spiraling even more out of control (via World History).

The original plan was for Caesar to be cremated on a funeral pyre in the Field of Mars after his March 20 funeral, but the angry crowd took the body, returned it to the forum, and burned it there. Interestingly, it's a history by Appian of Alexandria (via Livius) that shed a fascinating glimmer of light on just how important Antistius' autopsy and findings were to the Roman people — a people who were shocked and stunned by the sudden assassination of their leader.

Appian wrote that after Mark Antony's speech, the crowd called for the conspirators to be brought to justice. He said: "Someone raised above the bier a wax effigy of Caesar ... The effigy was turned in every direction by a mechanical device, and twenty-three wounds could be seen, savagely inflicted ... This sight seemed so pitiful to the people that they could bear it no longer. Howling and lamenting, they surrounded the senate-house, where Caesar had been killed, and burnt it down."

The reexamination

Along with Luciano Garofano's second look at Antistius's autopsy notes, History Collection says that he conducted a more modern investigation. Using the ancient physician's observations, Garofano used 3D imaging software to recreate the 23 wounds and get an actual picture of what Caesar's body would have looked like. Then, he staged a few recreations of the murder scene.

Exactly how many senators were involved in the conspiracy and the eventual assassination has always been a little unclear and ranges from National Geographic's 40 to History's 60. But how many actually got blood on their hands? According to Garofano, fewer than centuries of historians and criminologists have thought (via Forensic-Psych). He ran the scenario three times: First, he had 23 "attackers" stabbing their Caesar once each, then that was lowered to 11 attackers, then five. He quickly came to the conclusion that there was no way 23 men would be able to get a single stab thrust (short of some well-organized fight choreography and a victim that didn't mind being stabbed). It was even tough to juggle 11 attackers, and it ultimately led him to the conclusion that Caesar had only been stabbed by somewhere between five and 10 people.

Caesar probably knew his time was limited

Hindsight now has many experts suggesting that Julius Caesar knew that his time was limited, and some of the actions his contemporaries condemned as the insufferable loutishness of a man getting too big for his britches actually had roots elsewhere.

When some senators offered to shower their leader with gifts meant for a god, he infamously refused to stand — and it was a massive offense. He ignored portents and warnings and didn't read a letter he was handed just before the assassination, warning that he was in danger. That doesn't sound like the savvy politician and strategist he was known for being, and investigator Luciano Garofano's consultation with Harvard Medical School forensic psychiatrist Dr. Harold Bursztajn led to a surprising conclusion: Caesar already knew that he was dying (via Forensic-Psych).

Bursztajn believes that Caesar was suffering from temporal lobe epilepsy, which caused symptoms like seizures and a loss of control of the bowels, especially when under stress. That, he argues, is the real reason Caesar didn't stand for the senators, and it was his illness that led him to make some of the increasingly irrational decisions that ultimately led to his fall from grace. Add in his renowned vanity, and Bursztajn suggests that suicide began to seem a more attractive option than seeing his illness progress further. Rather than face a slow, public decline, Caesar may have decided to goad his assassins into helping him go out in a blaze of glory.

Did his last words have a long-hidden meaning?

History Collection says there's a fascinating bit of history that can be extrapolated from Antistuis' autopsy. The conclusion that only one of the 23 wounds was serious enough to kill him and that he ultimately bled to death makes it likely that yes, he definitely did have time for some final words — and the parting words of the real Caesar might be way more interesting than what Shakespeare's fictional version had to say.

Roman historians say (via Forensic-Psych) that his last words were actually, "Kai su, technon?" That's Greek for "You too, my child?", and here's what some historians think was going on. Cornell University's Barry Strauss believes that Caesar's last words were rehearsed and that he knew Brutus was going to be one of the assassins. He also argues that his last words were meant to be taken literally, as Brutus really was Caesar's biological child.

It's a theory that's not without merits. ThoughtCo. says that Caesar's long-running affair with Brutus's mother, Servilia, was widely known, and even though Caesar was only 15 years old when Brutus was born, the possibility was hinted at in the writing of ancient historians like Plutarch. That would make Caesar's last words mean something completely different: Not only was Brutus an assassin, but he had assassinated his own father. That was a whole other level of murder, and it would absolutely warrant his own special place in hell.

Going out on his own terms

Forensic investigator Luciano Garofano didn't just look at the physical details of Julius Caesar's autopsy — he also did some psychological profiling, too, and he came to the conclusion that Caesar's actions in the last months of his life were those of a man who wanted to make sure his name was never, ever forgotten (via Forensic-Psych).

Just six months before his assassination, Caesar wrote a new will naming his nephew, Octavian, his heir. Octavian would go on to be the first Roman emperor, and it was a pretty brilliant political move. Not only did it make sure someone in his bloodline remained at the top of Rome's political pyramid, but he also added something that guaranteed the Roman people would demand justice: He awarded every Roman citizen three months of living expenses, making sure they could mourn him properly ... and bring his assassins to justice.

The result? Everything that Caesar wanted. Harvard Medical School forensic psychiatrist Dr. Harold Bursztajn says (via Forensic-Psych) that not only did Caesar's political maneuvering and death by assassins guarantee he would be immortalized for thousands of years, but it also put him firmly on the right side of history. Assassins were vilified as he was deified, and according to the Smithsonian, those assassins met their own bloody ends pretty quickly. It turns out that Caesar's seemingly unexpected assassination may have been his plan all along.