Unsolved Murders From The Victorian Era

If you hang out with ... interesting people, you know that whenever the conversation naturally turns from made-up medical conditions to Victorian-era murders, everyone invariably thinks of Jack the Ripper. The brutal killer sliced his way through Whitechapel in 1888 and taunted the police but was never identified, even though the case had been pored over by sleuths, both amateur and professional, for over 100 years.

Part of the reason Jack the Ripper managed to live on in infamy is the completely insane mutilations that went along with the killings, but if you were so inclined to do some digging through Victorian history, you'd find he's not alone. It's almost as if committing horrible murders — and often getting away with them — was the fad of the day. It was a dangerous time to be alive, not just on the mean streets of London, but the rest of the U.K. and abroad. Here are some notable unsolved murders from the Victorian era.

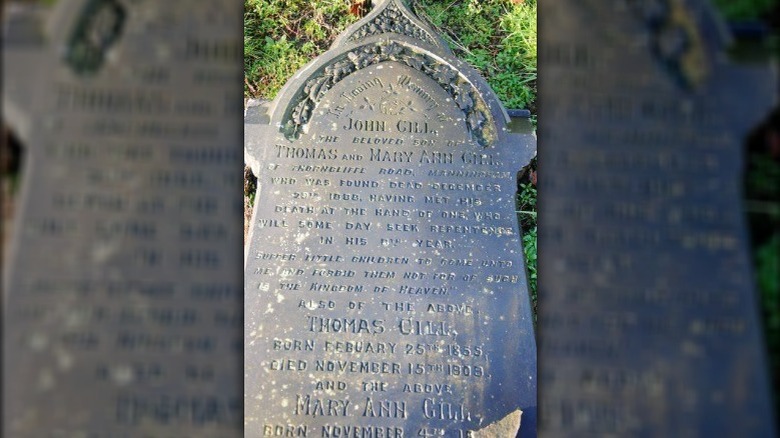

John Gill

John Gill was 7 years old when he was killed but he's often said to be 8 because his birthday was right around the corner. He was young enough that he was probably still excited about the prospect. The Ripper stalked London in the fall of 1888, and it was a combination of timing and savagery that linked Gill's murder to the Ripper killings, at least in the court of popular opinion.

According to Ph.D. student Lauren Padgett (via Leeds Trinity University), Gill went missing on December 27 in Bradford, north of London. He was found in a stable near his home on December 29, and at a glance, he was neatly dressed in his clean clothes. Those clothes hid the grisly truth: his arms, legs, and ears had been sliced off, his internal organs had been removed and placed on top of him, and his shoes were left inside his chest.

Police consulted with a chemist who had a proven track record, and his methods were impressive even today. He examined the body and the entire area at a microscopic level and found some clues. The boy had eaten a currant-filled bun not long before he died — perhaps a bribe? The body was wrapped in a newspaper from Liverpool, but the name and address on it were a dead end. They eventually did arrest a local man in connection with the killing, but the evidence was circumstantial and no one was ever prosecuted.

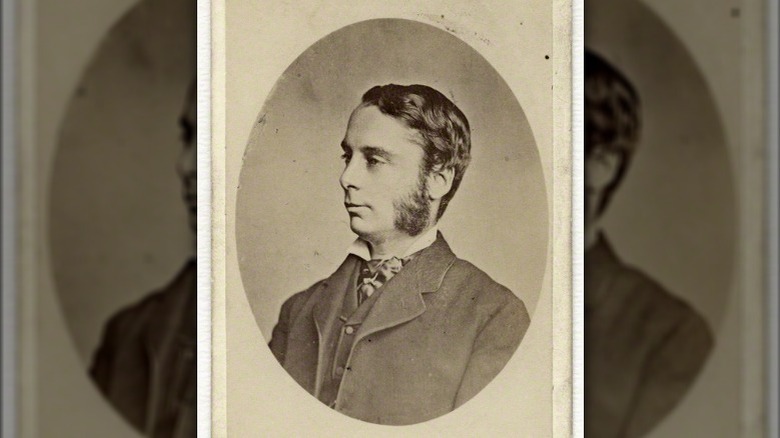

Charles Bravo

Charles Bravo died in 1876, succumbing to a slow and painful death brought about by some poison slipped into the glass of water on his nightstand. The poison was antimony, which kills slowly — slowly enough that he would have known what was happening. Bravo had all the time in the world to reveal who poisoned him, but he never did.

At the time, it was believed he must have killed himself because of the attitude he took to finding his killer. According to the BBC, we know today that the calm attitude is one of the effects of the poison, and it definitely turns this from a suicide to a whodunit.

Even Agatha Christie got in on the crime-solving, and it was quite the cast of real-life characters. Her money was on the doctor, who had not only given Bravo's wife Florence an abortion but who had become her lover. There was also the widowed maid who was about to be released from service, and then there was the wife herself. According to her, Bravo wanted kids but her constant ill health left her terrified a pregnancy would kill her. A contemporary examination of the facts suggests it was the wife in the bedroom with the poison, but since a lot of those facts are based on suspect testimony and we know how fond people are of lying, the case hasn't actually been solved.

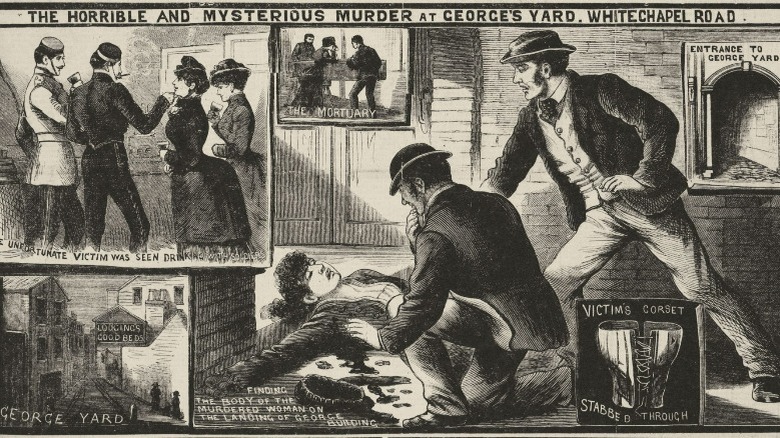

Possible (but debated) victims of Jack the Ripper

We don't know exactly how many people Jack the Ripper killed. There are five victims that are canon, so to speak, but according to Casebook, London law enforcement estimates went as high as nine ... sometimes. It's pretty fuzzy, but there are a few murders that have been strongly linked to the Ripper. (Maybe.)

Emma Elizabeth Smith was attacked early on April 4, 1888, and she survived a horrific beating and sexual assault. She died four days later, after telling London Hospital surgeons that three or four men attacked her. Next was Martha Tabram (pictured), killed on August 7, 1888, after she and a friend picked up a pair of sailors in a Whitechapel pub. She was killed with 38 stab wounds from a penknife and one from a bayonet.

Some debated victims came after the end of the Ripper's reign, including Alice McKenzie, killed July 17, 1889, by a number of stab wounds said to have required anatomical knowledge. The Pinchin Street murder victim, discovered in September 1889, was never definitively identified, as the body was missing the head and legs. Then there's Frances Coles, who was killed around February 12 or 13, 1891. She was still alive when she was found, and the attending police officer followed procedure and stayed with her instead of chasing her fleeing murderer. As horrible as these murders were, they were generally found not brutal enough to fit the profile of the Ripper. Now's a good time for some serious soul-searching about the horribleness of the human race.

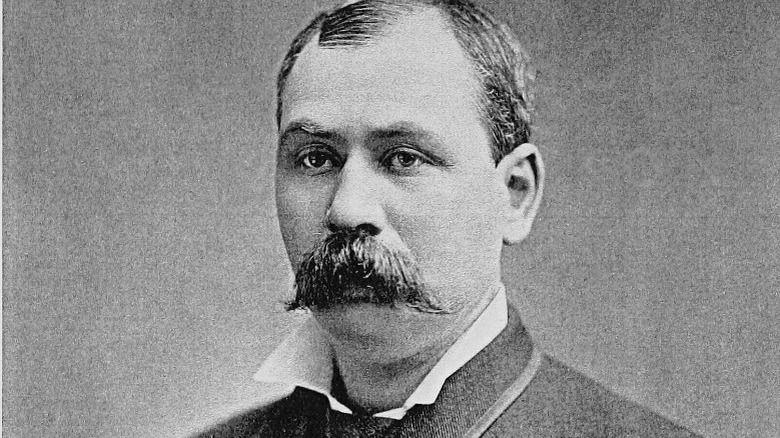

Carrie Brown

Carrie Brown has also been connected to Jack the Ripper, but she's a little different. She was murdered on the night of April 23, 1891, and her body was discovered in a Manhattan hotel room. Ameer Ben Ali was arrested for her murder and served 11 years in jail but was ultimately declared innocent, simply the victim of evidence mishandled by investigators. Yay, justice system!

Brown's case itself is a bit odd because, according to Casebook, the press tried to downplay the entire thing — presumably to keep panic from spreading — so there are only a few details known about what happened to her. We know one of the medical examiners wrote someone had tried to gut her, and she was covered with stab wounds. For a while, it was believed she was living near one of many Ripper suspects, although this is now in question, but stranger still is the murder's connection to the New York Police Department.

The New York Times had previously run an article quoting the NYPD's Inspector Thomas F. Byrnes (pictured), saying if Jack the Ripper tried to do his thing in New York, he wouldn't stand a chance. That's obviously not the sort of thing you want to go around saying, and there are theories suggesting Brown was murdered in such a way the NYPD could plant evidence and "catch" Jack the Ripper. Or, maybe was it the Ripper himself, sending a clear message of, "Hey, look what I can do." The jury's still out on this one.

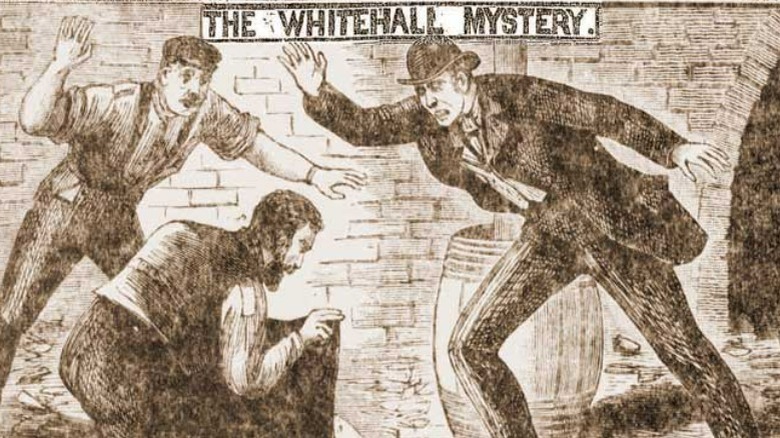

The Thames Torso Murders

The first part of the first body, the left half of a woman's torso, was pulled from the river on September 5, 1873. Over the next few days, police found the right half, parts of the lungs, a right thigh, right shoulder, left foot, right arm — you get the idea. It got worse when a scalp with a face still attached turned up. The skull was never found. The body was reconstructed as best as possible, the face was displayed on a butcher block, and the public was asked to help identify the victim (via the University of Leicester). One man believed it might have been his daughter, but he couldn't make a positive ID. (Talk about being haunted for the rest of your days.)

The London Times stayed on top of the so-called Thames Torso Murders, reporting on new batches of body parts in June 1874, May 1887, and September 1888. According to Casebook, one piece of that victim ended up thrown over the fence into an estate belonging to the family of Mary Shelley, the by-then-deceased author of "Frankenstein." An acknowledgment, perhaps? A thank-you for the inspiration? It's unclear just how many different killers were dismembering women during this stretch of London's history, but University of Leicester researchers believe it was at least three.

The Gatton Murders

In 1898, adult siblings Michael, Norah, and Ellen Murphy were heading home on Boxing Day evening after a fun day out. Whatever happened to them on their way from a canceled dance to their Queensland home has become one of Australia's most baffling unsolved murders.

According to the Queensland Police Museum, the three were found by their brother-in-law, who went to look for them when they didn't come home. He found a grisly murder scene: clothing was torn, the bodies were battered and bruised, and Michael and Ellen's skulls had been crushed. Rage was obvious — the killer (or killers) had even fatally shot the Murphys' horse. It's also worth noting whoever attacked them was no slouch — Michael was home on leave from the Mounted Rifles, where he had a reputation as being pretty bad***.

Police talked to more than 1,000 people, but there were outrageously large gaps in the investigation, even for the time. There wasn't just crime scene contamination: some members of the public took souvenirs. Police and the media went head to head, trying to decide who was more incompetent, and in the meantime, one of the two suspects (the one without an alibi), disobeyed police orders and scrubbed the blood from his shirt before it could be tested. He was a butcher, in all fairness, but still. All that bungling kept the Murphy family (pictured) from ever seeing justice.

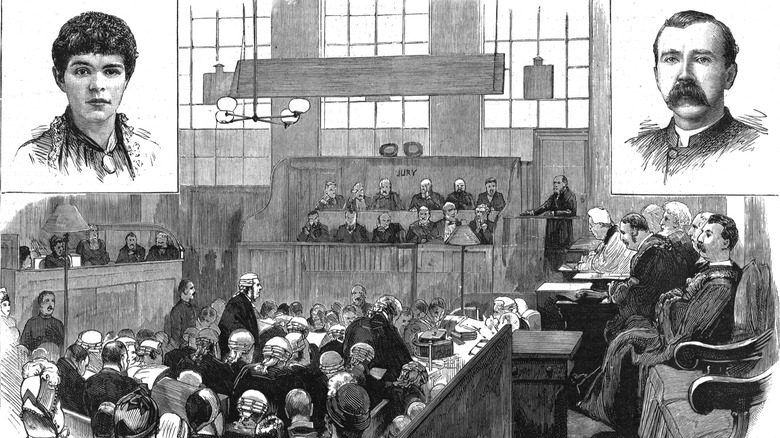

Edwin Bartlett

Edwin Bartlett's death was so strange, the British Medical Journal took another look at the case in 1994. It's still weird. Bartlett died on the evening of December 31, 1885, after undergoing dental treatment for his decaying gums, rotting teeth, and breath so bad that he and his wife slept separately. That had been the setup for some time, at least since August when a maid caught Mrs. Adelaide Bartlett in a rather compromising position with her tutor, the Reverend Dyson.

Adelaide went on trial for the murder of her husband, and one of the most damning pieces of evidence was the fact she had asked Dyson to buy her some chloroform a few days before Edwin died. She claimed it was for "an internal complaint" he was too embarrassed about to speak of himself. At the trial, it was brought up that the chloroform had disappeared, and the autopsy showed Edwin had so much in his stomach that examiners could immediately smell it when they opened him. Open-and-shut case, right?

Dyson was cleared of guilt almost immediately and claimed that Edwin thought he was terminally ill. That swung the court's opinion toward suicide and a not-guilty verdict for Adelaide. However, not everyone believed the suicide line. After the acquittal, a doctor at St. Bartholomew's Hospital said Adelaide "should tell us in the interests of science how she did it."

Harriet Buswell

Harriet Buswell is sometimes called an early victim of Jack the Ripper, but if that's the case, Jack waited a long time to start killing again. Buswell was killed in London on Christmas morning in 1872, and according to the research done by Arizona State University's Marlene Tromp (via Branch Collective), the series of events leading to her death began with a Christmas Eve trip to the Alhambra dance hall. There, she picked up a man described by witnesses as a well-dressed foreigner, probably German, and headed home with him.

Her landlady found her the next morning, her throat cut several times, with what police described as a peaceful expression on her face. The manhunt for the killer led to Dr. Gottfried Hessel, a German minister, on a stopover on his way to South America, but this was the good old days before things like forensics. Hessel was ultimately cleared because of his good character and alibi (his boots were very clearly left outside the door of his hotel room), even though his maid testified she had washed several bloodied handkerchiefs for him on the night of the murder. Suspicious? Probably, but Hessel was released, and the police were subjected to a good bit of ridicule for suspecting such a fine, upstanding citizen of such a horrible murder. No one else was ever arrested.

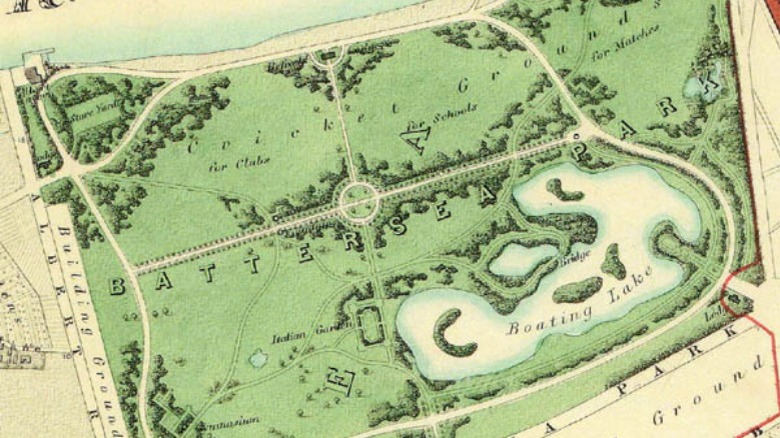

Elizabeth Jackson

A warning: this is about as grisly as it gets. Three boys poking around the Thames in Battersea on June 4, 1889, came across a human thigh, severed at the hip and knee. They wrapped it up and took it to the police, because ... well, who can tell? Almost immediately, news came in that the lower part of a woman's body had been found 5 miles down the Thames.

According to reports compiled by Casebook, police were debating how much of a body was actually needed to open an official inquiry when more parts started turning up. A Battersea Park gardener found a package containing some flesh, an empty torso was found in the Thames, an arm wrapped in a skirt showed up at Covington's Wharf, a right leg and foot were found wrapped in pieces of a tweed coat ... you get the idea. Over the next week, organs, pieces of organs, a left arm, hands, an empty pelvis, a bladder, and a right thigh turned up. The last piece was found on June 11, and on June 12, a male fetus, estimated to be around 5 or 6 months of gestation, was found in the Thames, too.

The reassembled body was identified as Elizabeth Jackson. Her family reported her missing in May, and a few major theories developed, including that Jackson was attacked and murdered in Battersea Park, that she died after a botched abortion, or that she was another of Jack the Ripper's victims. No one knows.

Emile L'Angelier

It's usually the killers — or the accused killers — that capture the imagination and attention of the public, and that's exactly what happened with Emile L'Angelier and Madelaine Smith.

The affair started in 1855, with a very literal affair. Letters revealed there was something going on between them that was unthinkable in Victorian society, and when Smith became interested in a gentleman who was a match her family would approve of, it seems L'Angelier made at least some attempts at blackmailing her. He later wrote in a diary that he became sick after seeing her, and he suspected he was being poisoned. The Scotsman quoted him as telling a mutual acquaintance, "If she were to poison me, I would forgive her." He didn't get the chance to forgive, and died on March 23, 1857.

Smith went on trial, not surprisingly, and according to the BBC, she testified as though she was "a belle entering a ballroom," and she explained away her recent purchases of arsenic by claiming she didn't use it as poison, but as a face wash. If there's anything good to be said about the insane beauty routines of the Victorian era, it's that they're a handy murder defense. She was found not guilty and released, while the case of L'Angelier's death was never satisfactorily resolved.

Eliza Grimwood

Everyone's a critic, and even the greats suffer their share of naysayers. When Charles Dickens published "Oliver Twist," it was (spoiler alert) the murder of Nancy that twisted critics' knickers. Condemned as too graphic, it was left out of most performances, and according to writer and researcher Rebecca Gowers (via The Guardian), it was based on the murder of Eliza Grimwood.

Accounts compiled by the Victorian Crime, Sex & Scandal blog give the grisly details. Her cousin found her body on May 26, 1838, and it was every bit as violent a murder as Dickens would later write. Her throat was cut, and she was covered with cuts suggesting she had fought her attacker to her dying breath. Blood covered the room, and a number of post-mortem stab wounds were found. Witnesses saw her with a respectable-looking man the previous night, and even though there were a few suspects, the case remained unsolved.

There are two weird footnotes in this case. The first is a contemporary theory that suggests she was killed by a hit squad hired by newspapers to make news on days there wasn't enough of it. The second is that the killer may have had another victim: Dickens himself. Dickens loved the scene, and once acted it out on stage so enthusiastically that friends said it damaged his health, encouraged a stroke, and led to his death.