The Untold Truth Of Olive Oatman

Many tales of the Wild West follow an established set of rules with reliable stock characters. There are the pioneers making their way west, dogged by opportunistic charlatans and hostile native people. There are harsh environments and scarce resources. There are good guys and bad guys. And, despite moments where the worst has already seemed to happen, there is always the chance of return and redemption.

Upon first glance, this seems like the story of Olive Oatman. Captured by American Indians after a massacre, she lived with two different tribes for years before returning home. The account of this period, "Captivity of the Oatman Girls," fits in with the wider form of American captivity narratives, which Oxford Bibliographies notes had been around for well over a century by Olive's time.

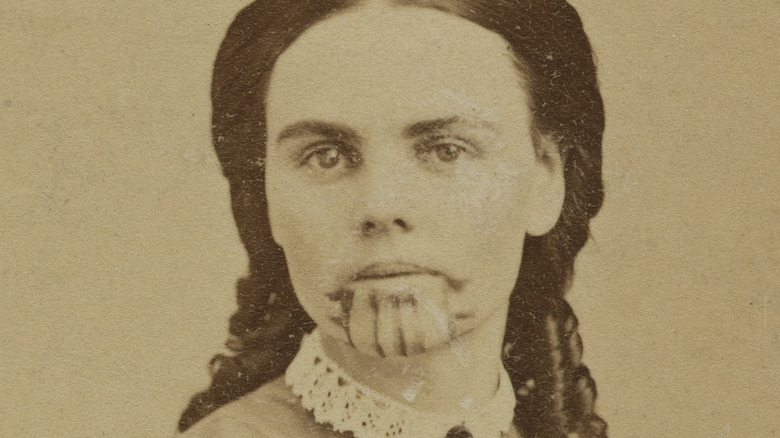

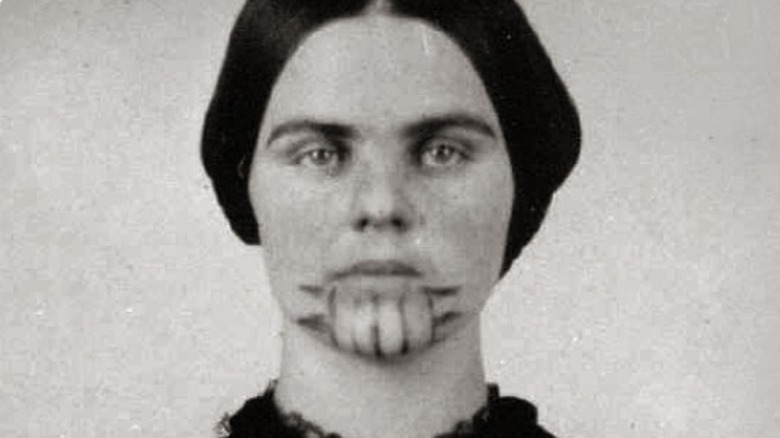

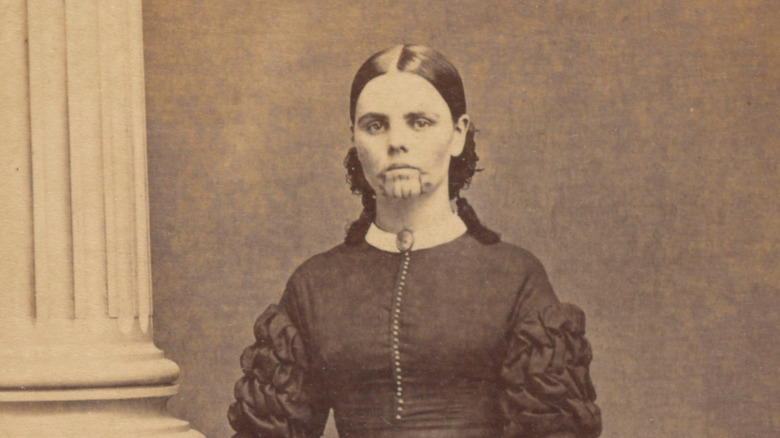

Yet, a deeper look uncovers complications. Olive's relationship with the Mohave people was far more complex than many initially believed, as was her relationship with her fame. And, of course, there is the matter of one very prominent factor: her tattoos. The blue marks on her chin would have been de rigueur amongst the Mohave, but they quickly made her a figure of tragedy and curiosity when she came back and tried to reintegrate into the society she was born into. But what's the real story behind the sensationalism? This is the untold truth of Olive Oatman.

The Oatman family were Mormon pioneers

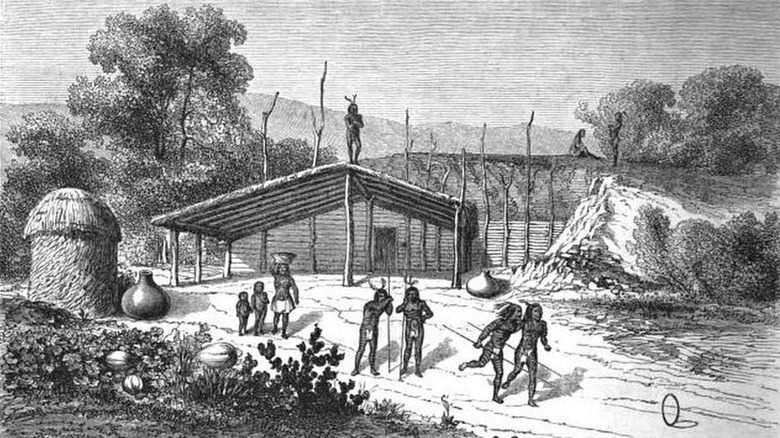

In many ways, the Oatmans were like any other pioneer family, driven to seek a new start by social and religious movements. According to "Intimate Frontiers," they were part of a group known as the "Brewsterites," who left Independence, Missouri in August 1850. The family, who had started from Illinois, consisted of father Royce (sometimes spelled "Roys"), mother Mary Ann, and their seven children (via "The Oatman Massacre").

According to the Brigham Young University Library, the Brewsterites were followers of Latter-day Saints church member James C. Brewster. After the death of LDS founder and prophet Joseph Smith, Brewster claimed that he was also receiving messages from on high. The communications supposedly told Brewster that he was supposed to lead the faithful to the promised land and found a city called "Bashan" in the Rio Grande Valley. Yet, arguments arose and many of Brewster's followers left him and continued on to California. The Oatmans likewise split from Brewster along the way, but they would never make it to the west coast.

Disagreement caused the Oatmans to isolate themselves

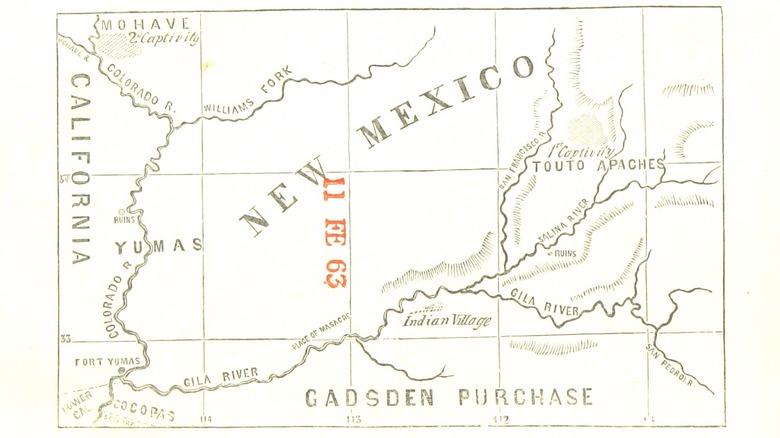

According to "The Blue Tattoo," the first real problems for the Oatman family began after they entered the New Mexico Territory. The Brewsterites squabbled about who should be the leader of the enterprise. Royce Oatman was ultimately appointed "captain" by Brewster. Yet the two men butted heads and eventually decided to part ways. Royce led a little more than half the group farther west into the territory.

But the way proved to be tough, with difficult terrain, horse thieves, harsh weather, dwindling supplies, and hostile native people. At Maricopa Wells, in what's now Arizona, the group was warned to avoid the trail ahead, given reports of attacks by the Quechan and the forbidding landscape (via "The Blue Tattoo"). Most of the members of the group stayed put. But Royce, unable or unwilling to wait for better conditions, forged ahead with only his family.

In her account of the incident shared in "Captivity of the Oatman Girls," Olive said that her father was worried about their lack of food and vulnerability to attack even if they stayed at Maricopa Wells. He moved forward only "with much reluctance," but did so all the same.

The Oatmans were attacked in February 1851

As they traveled along the trail, the Oatmans became increasingly isolated and vulnerable. In an account she later gave to the Sacramento Daily Union in 1856, shared in the California Historical Quarterly, Olive Oatman gives scant details about the attack itself. "Captivity of the Oatman Girls," published in 1857, gives more detail, though it follows the melodramatic style of other 19th-century captivity narratives and may have been overly influenced by a preacher named Royal B. Stratton, as the journal Prospects notes. The 1857 narrative states that a group of native men approached the family one evening while they camped near the Gila River.

The men smoked with Royce, then asked for food. Noting his family's dwindling supplies, Royce declined to give them more than a small amount of bread. This seemed to cause the attack. The men began violently clubbing the Oatmans. Olive noted that "I was struck blind and senseless" (via "Captivity of the Oatman Girls") though not so thoroughly that she didn't see the destruction of her parents and five of her six siblings. Only younger sister Mary Ann was seemingly spared.

Olive later identified the attackers as Tonto Apache, likely because the local Pima and Maricopa people were afraid of that tribe's activities, per "The Blue Tattoo." But, as "The Oatman Massacre” argues, the assailants were more likely members of the Tolkepaya tribe of the Western Yavapai.

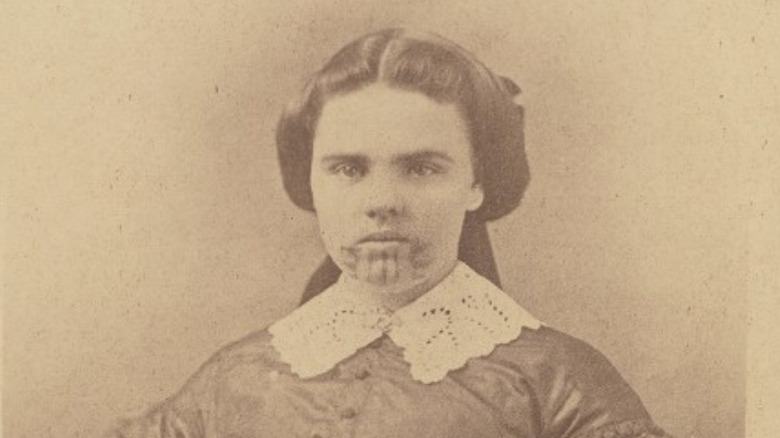

Olive and her younger sister were taken captive

Eleven-year-old Olive Oatman and her 7-year-old sister, Mary Ann, were taken captive and, as reported in "Captivity of the Oatman Girls," were forced to march to a remote camp.

Harsh as their treatment may have been, the practice of taking captives was nothing new. Tolkepayas were known for occasionally taking women and children as captives, reports "The Oatman Massacre." In fact, taking people into bondage and treating them poorly, oftentimes as an act of vengeance for prior losses, was practiced by quite a few tribes across North America. Besides taking an eye for an eye, captive-taking could also replenish devastated populations and provide income via ransom. Whatever the reason for their captivity, Olive and Mary Ann were eventually put to work in a Tolkepaya settlement, facing beatings if they did not follow commands.

Though Olive and Mary Ann assumed that everyone else in their family had been killed, their teenage brother Lorenzo had survived. As Lorenzo recalled it, he had been badly injured, then kept reviving and losing consciousness in the hours after the attack, per "The Oatman Massacre." He was eventually able to gather enough strength to trek back to a settlement where, upon hearing his story, a group traveled to the scene of the attack. They found the remains of six of the Oatman family, but no sign of Olive or Mary Ann.

The Oatman girls were traded to the Mohave

Olive and Mary Ann Oatman's time with the Yavapai was difficult, but after about a year with the tribe, they were to change location yet again.

According to Oatman's account, Topeka, the daughter of Mohave chief Espaniole, took pity on the abused girls during a previous encounter with the Yavapai. She brokered a trade for the two and effectively adopted them into her family. In the story as it was filtered through Royal B. Stratton, however, Olive remained suspicious, claiming that deception was "as natural to an Indian as his breath." From her perspective, it was very possible that she and her sister were to be handed over for yet more abuse.

However, that assumption would be proven thoroughly wrong. Upon their arrival in the Mohave village, Topeka's family greeted the group warmly and served the girls food (via "The Blue Tattoo"). Their appearance was even marked by singing and dancing. Shortly thereafter, Espianole told everyone gathered to always help the new arrivals and to "treat them well."

Olive's claim that they were Mohave captives is suspect

At this point, Olive Oatman's story becomes increasingly tangled. In "Captivity of the Oatman Girls," the narrative consistently refers to her and her sister as "captives" and emphasizes the harshness of their lives.

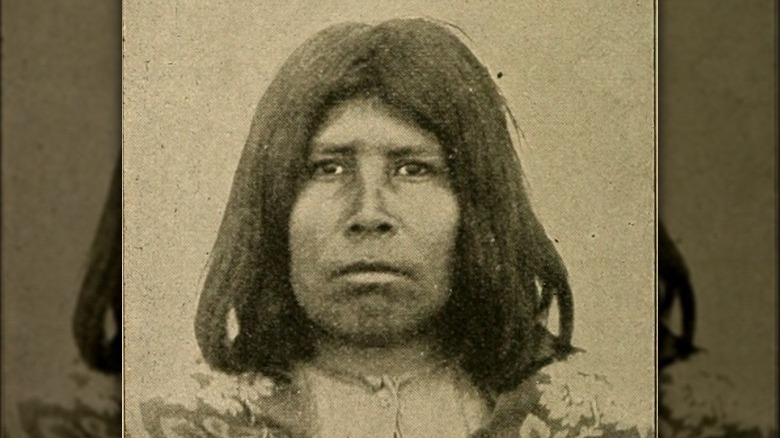

Yet, though Olive would later claim that the Mohave kept her against her will, evidence indicates that she and Mary Ann were effectively considered tribal members and could leave at any time. That's certainly what she first told newspaper reporters (via California Historical Quarterly). Then there was the matter of the tattoo. When she returned to white society, Olive came with an impossible-to-miss series of lines tattooed on her chin. As "The Blue Tattoo" notes, she also sported similar marks on her upper arms. Far from marking her as an inferior captive, these were designs worn by other Mohave women. She also received both a clan association and a potentially lewd nickname that further marked her as one of the group (via "The Blue Tattoo").

According to "The Oatman Massacre," Olive even declined to approach railroad surveyors who were in close contact with the tribe in February 1854. At no point during this time did Olive or Mary Ann try to escape. Neither is there any evidence that the Mohave hid the two girls from the workers. Certainly, this incident is conveniently left out of any of Olive's statements after her return, including "Captivity of the Oatman Girls."

Mary Ann Oatman died of starvation

After surviving the massacre, the time of servitude with the Yavapai, and being welcomed to Mohave life, Mary Ann Oatman (and everyone else in the tribe) was faced with an equally serious issue: starvation.

The 1855 harvest was especially poor for the Mohave, according to "The Blue Tattoo." Everyone in the tribe was reduced to foraging and parceling out increasingly meager reserves to make it through the difficult times. Even so, numerous people in the village died, including children. Mary Ann herself eventually realized that she, too, was growing close to death. She eventually died of malnutrition. At that point, Olive believed that she was the last member of her family alive. In "Captivity of the Oatman Girls," she wails that Mary Ann was "the last of our family dead, and all of them by tortures inflicted by Indian savages."

However, other accounts maintain that Mary Ann was mourned not only by her biological sister but by other members of the tribe, too. Aespaneo, the wife of Espianole, began grieving for Mary Ann alongside Olive, per "The Blue Tattoo." Both she and Topeka comforted the older girl as well and ensured that Mary Ann was properly buried. What's more, Aespaneo is credited with saving Olive's life, feeding her from a cache of cornmeal intended for future use before the older Oatman girl suffered the same fate as Mary Ann.

Olive finally left the Mohave in 1856

About five years after she was abducted, Olive Oatman's time with native people was nearly over. It began with the arrival of Francisco, a Quechan man. He carried a message that the people at Fort Yuma had heard rumors of a white woman living nearby. Fearing reprisal, the Mohave encouraged Olive to leave for the fort. As "The Oatman Massacre" reports, that worry was warranted. Francisco reportedly said that natives were in mortal danger if they didn't produce this white woman. He claimed that millions of white people were ready to kill the tribe if Olive remained hidden. A council debated keeping her, releasing her, or even killing Olive to cover up her existence.

A gentler version was related to anthropologist Alfred Kroeber by Mohave tribal member Tokwatha. He said that Francisco went straight to Espaniole without any council. Both the leader and his family expressed serious reluctance to let Olive go, saying that she was well-liked and effectively a family member. But, even so, they worried about further harm if more people were to come looking for Olive.

Eventually, Olive traveled to Fort Yuma and was "recovered" there in 1856. She reunited with her brother Lorenzo and, as the California Historical Quarterly notes, was given numerous offers of support from private citizens and the state of California. However, few followed through with actual help and her remaining family members certainly weren't rich. Olive would have to figure out how to support herself long-term.

Royal B. Stratton sensationalized Olive's story

Olive Oatman's experiences might have remained obscure if it weren't for an opportunistic preacher named Royal B. Stratton. According to the journal Prospects, it's not entirely clear how Stratton became involved with the Oatman siblings, but he somehow ended up taking dictation from both Olive and Lorenzo to create "Captivity of the Oatman Girls."

The way Oatman's story was presented played into existing prejudices and preconceptions about supposedly "savage" indigenous people and their interactions with "civilized" white settlers. It also apparently played into Stratton's need to be a literary stylist, with dramatic flourishes and florid speeches that may or may not have ever happened, says Prospects. If you compare the drama of "Captivity of the Oatman Girls" with the earlier, less embellished accounts given directly by Olive herself, it's clear that Stratton took some liberties. What's more, the Coalition of Feminist Scholars in the History of Rhetoric & Composition notes that there are significant differences between Olive's recorded words, such as during her lecture tour, and the style of her words in Stratton's colonialist book.

Olive had conflicted feelings about leaving the Mohave

Contemporary reports state that Olive Oatman was clearly upset upon her return to white society. Susan Parrish, who had befriended the Oatmans before the massacre, was struck by the young woman's behavior, going so far as to describe her as a "grieving, unsatisfied woman" (via "The Oatman Massacre"). She concluded that Olive must have left behind a young family. However, Mohave tribal member Tokwatha, speaking to Alfred Kroeber, claims that such a major development in Olive's relationship with the Mohave would have been remembered.

There is some circumstantial evidence that Olive Oatman never fully moved on. According to "The Blue Tattoo," she later suffered from persistent headaches and depression, perhaps linked to both her family's deaths, her departure from the Mohave, and her subsequent status as something of a sideshow attraction.

But what about the oftentimes racist "Captivity of the Oatman Girls?" Olive may have only teamed up with Stratton to earn a living. In "Violent Encounters: Interviews on Western Massacres," Margot Mifflin (author of "The Blue Tattoo") notes that Olive had to navigate her post-Mohave life as a single woman with little education and little chance of marriage, given her tattooing. Capitalizing on the tattoo and the story that went with it, even to the point of stretching the truth and playing to readers' assumptions, helped her earn a living and assured readers that she hadn't really gone over to the other side.

Olive Oatman's tattoos made her a curiosity

Though many things came together to make Olive Oatman a celebrity in her time, her tattoos were undoubtedly one of the most striking things about her experience. For white audiences, the dark blue lines on her chin were utterly shocking. Eventually, she falsely claimed that they were a mark of enslavement and newspaper accounts breathlessly spoke of "savage masters" who forced disfigurement upon an innocent young woman (via Western American Literature). If nothing else, it surely helped her to sell tickets to her lectures. "You perceive I have the mark indelibly placed upon my chin," she would tell audiences, before telling them to buy her book for the really juicy details and likely selling photographs of herself prominently sporting the tattoo, per "The Blue Tattoo."

If you were to ask a Mohave person, however, chances are good that they would have scoffed at such an idea. After all, weren't most people in the tribe tattooed in just such a manner? And, as "The Blue Tattoo" notes, Mohave people had to choose to receive tattoos — they were never forced upon anyone, captive or otherwise. In fact, many tribal members reportedly believed that the markings were necessary for Mohave people to recognize each other in the afterlife. Within that context, Olive's tattoos make it clear that she was part of Mohave society, both in the world of the living and of the dead.

Olive Oatman married in 1865

In 1865, nearly 10 years after her return, Olive Oatman married rancher John Fairchild. According to "The Blue Tattoo," she moved with him first to Michigan, then Texas.

Their marriage was by all accounts a peaceful, loving relationship, though it required a somewhat dramatic break from the past before the couple could move forward. Olive's new husband reportedly burned as many copies of "Captivity of the Oatman Girls" as he could before the wedding. He may have also encouraged her abrupt break with Stratton, which happened around the time of her marriage. At any rate, she didn't need the opportunistic preacher anymore, having achieved financial and social security for what was arguably the first time in her life.

The Fairchilds ultimately settled into a quiet life in Sherman, Texas. The pair never had biological children, though they did adopt a daughter named Mary Elizabeth "Mamie" Fairchild, raising her in a rather nice mansion courtesy of John's considerable income (via The Dallas Morning News).

In her later years, she rarely commented on her life with the Mohave

Often described as fairly shy, the older Olive Oatman Fairchild rarely spoke about her experiences with the Mohave people, though she undertook charity work with orphans that echoed her own parentless status. Her obituary mentioned that she sometimes wore a veil to conceal her tattoo (via "Violent Encounters").

It appears that even though she didn't publicly discuss her dramatic story after the end of her business relationship with Royal B. Stratton, the effects of her trauma dogged Olive throughout her life. According to "The Blue Tattoo," she often suffered from depressive episodes in her later life and even traveled to a medical spa in Canada to treat her "neurasthenia," which was effectively a nervous breakdown. In private letters, the older Olive sometimes even wrote of her long-dead family, telling one friend in 1882 that "I long to have my dear mother back." She died in Sherman, Texas in 1903.