Why The History Of Urinals Is So Cloudy

Urinals and easy, safe, convenient access to them are important aspects of day-to-day life that people tend to take for granted, until they're unavailable in some way. Per How Stuff Works, there are around 8 million urinals in the United States, used by 100 million people annually and consuming 160 million gallons of water. However, people have needed to use bathrooms long before modern plumbing systems, and the need for a receptacle for urine that's open to the public and, for efficiency's sake, available to more than one person at a time goes back to the beginning of humanity.

According to AYS Rentals, the first known public toilets date back to A.D. 74 A.D., were found in Italy, and consisted of "chambers" placed next to each other. The first known standing versions and predecessors to today's modern urinals were discovered in Sri Lanka. As reported by Sri Lanka Travel and Culture Services, ancient Buddhist monasteries had cesspits and clay pots within the ground with carved "footstones" to indicate where the urinal user should stand to use the in-ground portion of the system.

Andrew Rankin brought urinals to the masses

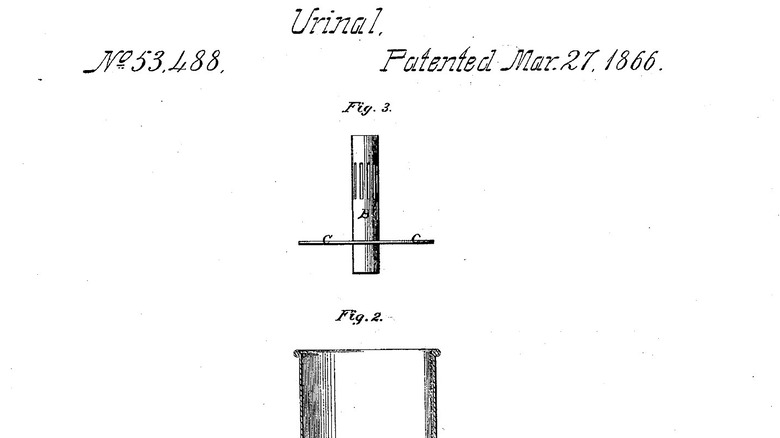

The patent for urinals within the United States (US53488A) was granted on March 27, 1866 to Andrew Rankin of New York, New York. Within his application, Rankin noted his plans for his "urinal bowl": "to adapt it for the reception and retention of a deodorizer of the obnoxious and unpleasant odors emitted by the urine discharged by persons into the same." He also described the privacy and hygiene aspects of installing individual partitions along one communal urinal bowl, writing in the application, "my improvement for urinals where one bowl is used, but which is partitioned off so that more than one person can be using it at one and the same time and yet not be exposed to each other."

As reported by Pop Matters, Rankin's "upright flushing apparatus" was immediately a hit in northern cities within the United States where populations had boomed after the Civil War. Both New York and Chicago had to upgrade their public sewer systems, with New York even bringing in water from the Catskills Mountains to keep up with the demand for cleaner, better systems servicing never before seen numbers of people.

Paris was famous for its public urinals

Pop Matters went on to note that within the United States, urinals came into wide use during the United States' industrial revolution. This made owners and managers of factories and other workplaces that employed lots of men interested in on-the-job efficiency, standardization, and organization. The presence of urinals, particularly when placed close to factory floors, meant greater convenience and comfort for the workers, and men tended to spend less time at urinals than in stalls featuring traditional toilets.

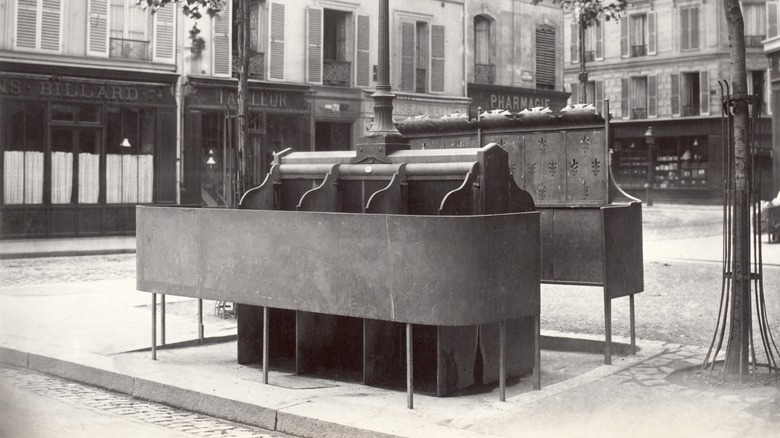

Cities outside the United States also experienced rapid growth during the 19th century. As reported by Paris Update, Paris, France installed their first outdoor urinals, known as pissoirs or vespasiennes (shown above) in 1841. They didn't catch on at first, but by the late 1800s there were hundreds of these structures all over the city, recognizable by their trademark green color and providing a small amount of privacy via steel screen.

Not in my backyard?

Per Paris Update, by the 1930s Paris, France contained around 1,200 pissoirs, and they became a source of much interest and amusement among foreign tourists visiting the city. By 1966, just 329 remained, and by the 1980s they were replaced by public sanisette toilets, which are more easily used by anyone in need of a bathroom break, regardless of their anatomy. As reported by French Moments, as of 2017 there were 420 sanisettes available around the city, with just one vespasienne remaining on Boulevard Arago near the Santé Prison. It is apparently still in use by the public and has the unpleasant smell to prove it.

Despite the presence of sanisettes, public urination remained an issue in Paris. In 2018, per CNN, city officials installed bright red, open air uritrottoirs in "problem areas" where large numbers of people had been seen relieving themselves. The new school public urinals were even eco-friendly and meant to harness the nitrogen, phosphorous and potassium found in urine to create compost to be used in the city's parks and gardens. Nevertheless, angry residents wrote to town hall insisting they were unattractive and made their neighborhoods less desirable.

The problem with 'wild peeing'

The Netherlands also has a long, fraught history concerning urban public urinals. Like Paris, Amsterdam and other Dutch cities have distinctive green screens around public urinals, or kruls, and per Dutch Review, the curl-shaped design has led to the structures being nicknamed "pee curls." In the city of Utrecht, they don't even have a screen and the entire back of the person using the public urinal is, well, public. Historically, the decision to install urinals instead of toilets that would serve the entire population instead of just half of it came from the decision of a "urinal committee" that decided men were more likely to work on the street and therefore urinals were the more cost effective and efficient option.

Like Paris, Amsterdam has attempted to install eco-friendly public urinals to combat what they call "wild peeing." As reported by CNN, the GreenPee urinals look like planters and as of 2020 there were 12 installed around the city. A 2018 pilot project for which four GreenPees were installed in areas particularly prone to wild peeing showed a 50% reduction in instances of public urination, which GreenPee inventor Richard de Vries called "a great success." De Vries has gone on to install GreenPees in the Dutch cities of Vlaardingen and Beekbergen, and the Belgian cities of Mechelen and Genk.

The urinal as art

Despite the long and colorful history of the urinal, its true origins remain unclear and it's unlikely that there will ever be a complete history of its place in people's day-to-day lives and its complete impact on culture and society. Nevertheless, a particularly famous urinal remains at the forefront of the art world over 100 years after its premier. In 1917, per Tate galleries, French-American artist Marcel Duchamp obtained a standard urinal, signed it "R. Mutt 1917," named it "Fountain," and submitted it to the Society of Independent Artists, a group he had helped found, for display at the society's April 1917 inaugural show in New York at Grand Central Palace.

The board instead voted to exclude the piece, calling it indecent. Duchamp quit the board in protest and arranged for a photograph of "Fountain" to be taken by Alfred Stieglitz. As the original "Fountain" was lost, the photograph became the primary documentation proving that the work existed at all. Duchamp later authorized replicas of Fountain in 1950 and 1963, and Tate contains one signed by Duchamp in 1964. In 2004, as reported by the BBC, "Fountain" was voted the most influential modern art work of all time in a poll of 500 art experts.