How Harry Houdini Called Fraud On Spiritualism

Even now, almost 100 years after his death in 1926, Harry Houdini's name means magic. He was one of the biggest entertainers of his time, one whose illusions and daring escapes thrilled audiences around the world. But magic was just a part — an admittedly large part — of Houdini's career. He starred in films, flew airplanes, and spent a good chunk of his time debunking spiritualists: mediums, psychics, and the like who rose to prominence during the 1800s, and whom Houdini largely considered frauds. The Victorian Era (1837 to 1901) was marked by a rabid interest in all things magical and mystical on both sides of the Atlantic that continued into the early 20th century. This movement helped propel Houdini's career, but it was also a burr in his side.

Houdini had a twofold axe to grind with spiritualism: professional and ethical. Professionally, as he explained in a 1925 article he wrote for Popular Science Monthly called "How I Unmask the Spirit Fakers," he considered mediums to be cheap imitators of true magicians like himself. Ethically, Houdini likened mediums to vultures preying on the vulnerable, particularly those mourning the deaths of loved ones. Spiritualists offered comfort, but the comfort of a lie. Houdini was so committed to taking down spiritualists that he didn't just write papers criticizing them — he took his case all the way to Congress in 1926 to try and outlaw the practice in Washington, D.C.

The rise of spiritualism

Houdini's turn-of-the-20th-century career happened lockstep with a massive cultural interest in spiritualism and the occult in the United States and around the globe dating back to the 1840s. As a self-described "religious" movement, it focused on finding ways for the living to communicate with the dead. Spiritualism took root in the Industrial Revolution and reflected a desire amongst people for greater meaning to life than the machine-based advances of the age implied — one that would console people in the U.S. after its Civil War by validating belief in life after death.

But as soon as spiritualism took hold, so did hucksters. For instance, New York sisters Maggie and Kate Fox claiming to receive messages from the dead in the form of knocking sounds. Would-be believers latched onto these claims even though the girls were debunked in 1851. Come 1888 Margaret confessed to the deception, but later retracted the retraction and stated that it, too, was a deception.

Even beyond a desire for confirmation of life after death, spiritualism was simply entertaining. It was a form of public show and pageantry regardless of whether or not those in attendance at spectacles were true believers. But for true believers, the dismissal of all but belief — especially dismissal of data-driven evidence and science — is precisely part of the appeal. Electricity, for example, is invisible and moves around unseen, so why not ghosts and specters?

Many ways to trick an audience

After the Fox sisters' knocking — aka "spirit raps" — were debunked, other spiritualists developed more complex methods of invoking the great beyond. Some mediums took to vomiting out wads of cloth and calling it ectoplasm, a sticky, ghostly goo that supposedly manifested during supernatural interaction. Others tried spirit photography: double-exposed photographs that showed apparent ghosts in the background. Yet others turned to talking boards, the most famous of which is the brand-named Ouija board, which hit the market in 1980. Yet others turned to techniques like sleight of hand and specially-designed trick props, the same used by stage magicians.

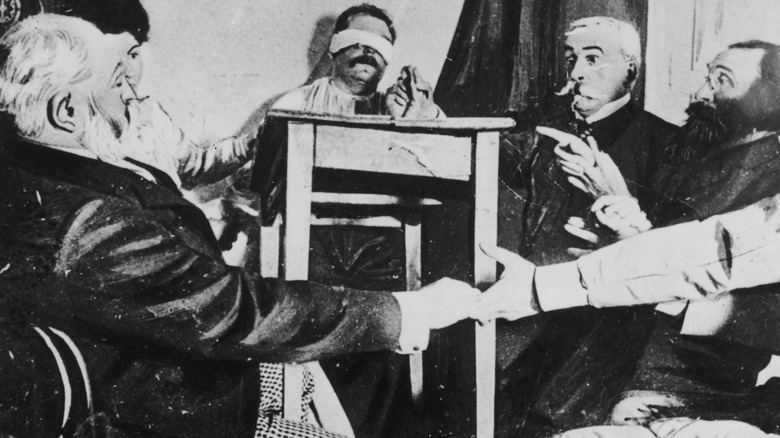

Oftentimes mediums would have those in attendance at a séance hold hands, as Harry Houdini wrote in a 1925 article for Popular Science Monthly. Ever shrewd, Houdini simply pointed out that mediums used their feet to produce noises instead, or released their hands and then made noises, or threw their voices like ventriloquists to make it sound like spirits were speaking around the room. As a magician himself, Houdini had a vested interest in exposing such individuals as frauds and portraying himself as authentic by contrast. According to the 1903 book "Mysteries of the Séance and Tricks and Traps of Bogus Mediums," some spiritualists even held their séances in a room specially wired to help them create sounds and other effects.

Houdini's distaste for spirtualists

In his 1925 article for Popular Science Monthly Harry Houdini talked not only about his methodology for exposing spiritualist frauds, but his virulent dislike of them. On one hand, he considered them an amateurish blight on his profession. One medium's psychic powers were "merely a crude adaptation of those by which professional magicians mystify audiences from the stage." In other words, mediums were tasteless, low versions of true stage magicians.

Houdini's other gripe was ethnical. People attend magic shows knowing that the whole thing is fake, and experience wonder because they can't figure out how a magician does this or that trick. Spiritualists, on the other hand, presented themselves as genuine, and were therefore snake-oil salesmen. It's worth quoting Houdini in full to get a sense of his disgust for such people. In his Popular Science Monthly article he wrote, "Thirty-five years among these vultures has convinced me that they are the most contemptible and the meanest criminals that walk the earth. The confidence man, the burglar, the pickpocket, the highwayman, and others who live by robbing their fellows, must take chances. They meet their victims on even ground and triumph through their wits, their strength, or their courage." Houdini then condemns spiritualists for exploiting those who grieve and milking them for money, saying that the "medium adroitly worms their secret out of them [their victim/audience], plays upon their fears or their grief" and "strips them bare of everything they own."

Houdini testifies before Congress

Harry Houdini made it his personal mission to shut down spiritualists manipulating the public for money. In fact, he lobbied Congress directly for four days in 1926 to pass House Resolution 8989 to outlaw "fortune telling" in Washington, D.C. Specifically, he proposed that "any person pretending to tell fortunes for reward or compensation" be fined $250, or about $4,260 in 2023 adjusted for inflation.

As Atlas Obscura describes, Houdini leveraged his name and clout to call the meeting and decry mediums and psychics on the spot, right there in the court. He demanded, for instance, that any medium present — anyone at all — tell him the contents of an envelope he carried. None of them stepped up. Houdini, wielding his presence and knack for stagecraft, called spiritualists "frauds from start to finish," "mental degenerates," and "deliberate cheats."

In response, spiritualists turned to the U.S. Constitution's First Amendment and claimed their beliefs to be religious, and therefore protected. The "prophecy, spiritual guidance, and advice are the very foundation of our religion," spiritualist Jane Coates stated in court. Coates also described prominent senators' interest in séances, and how President Calvin Coolidge even held a séance in the White House. In the end, Congress sided with the spiritualists and denied Houdini's proposal. But Houdini still succeeded – he'd crippled public confidence in spiritualists, and the movement subsequently died. Incidentally, the U.K. passed its Fraudulent Medium Act of 1951, making it a crime to conduct fortune telling "with intent to deceive."

Escaping the afterlife

Interestingly, and despite a lifelong mission to debunk spiritualists, Harry Houdini didn't necessarily consider himself a disbeliever. He simply wanted actual, verifiable proof that mediums were authentic. In his article on Popular Science Monthly he wrote that despite his "activity in exposing fraudulent mediums," he was "not a skeptic" when it came to spiritualism itself. "Although I have found no genuine physical phenomena medium," he said, "I have still an open mind. I am willing to be convinced — even to believe, if a medium can demonstrate to me that he actually possesses true psychic power."

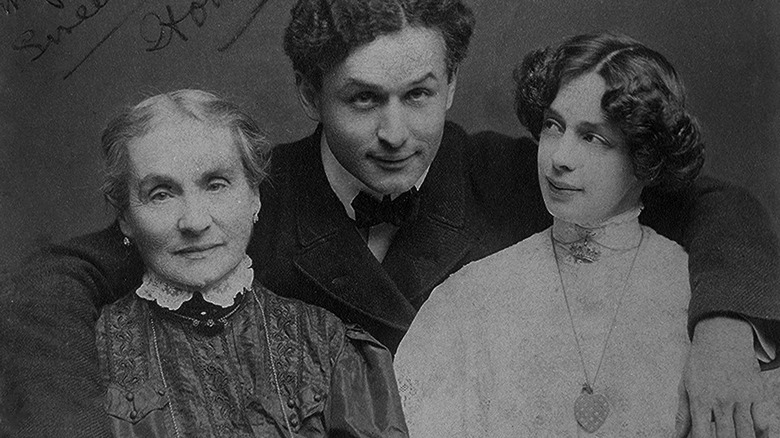

Doubly interestingly, Houdini left instructions for his wife Bess to hold séances to try and reach him after he died, as The Guardian describes. Either in an attempt to prove that spiritualism was legitimate (if not spiritualists), or to perhaps posthumously snub his nose at all the fakers he'd debunked during his life, he developed a secret code with Bess that he would use to indicate that it was him in the room during a séance: A combination of the word "believe" and the name of their favorite song, "Rosabelle."

Houdini died on Halloween in 1926, the same year he testified before Congress. His wife Bess carried on séances for 10 years on the anniversary of his death, unsuccessfully, before passing on the duty to others. Houdini fans still conduct séances every year for the same purpose, but Houdini hasn't spoken to any of them.