Why Victorian Factories Were So Deadly

For many people with a passing knowledge of the Victorian era, it's a given that life was hard. Only, that's not necessarily true. According to History Extra, this time in British history was a complicated one, with a growing emphasis on reform and social mobility that could lift people out of poverty if they could combine hard work with a decent helping of luck.

Yet, we can't ignore the plight of the factory worker. While it's clear that life as a Victorian wasn't all that bad, it's unfair to pretend like it was all sunshine and roses. While the people taking up work in factories across Britain were taking advantage of economic opportunities that wouldn't necessarily have been available to their parent's generation, that sometimes entailed serious sacrifices. As per History, laborers faced extensive discrimination, poor wages, environmental havoc, and even potentially deadly consequences. What's more, their physical and mental health, not to mention their very lives, were put on the line in the name of profit.

Yes, death was an all-too-common work hazard in Victorian factories. From chemical exposure to poorly shielded machinery to long-term stress, laborers faced doom at seemingly every turn. So, next time you're feeling on edge about getting that report in on time or sending yet another email (that will be ignored yet again), take comfort. At least it probably won't take your life just to manufacture some yarn. Don't believe that Victorian workers had it so bad? Prepare to be surprised. This is why Victorian factories were so deadly.

Working hours could be brutal

For many Americans today, a 40-hour workweek is now considered to be the standard, though quite a few of us are subjected to overtime or, for some small business owners and entrepreneurs, may quasi-voluntarily choose to work even more hours. But the Victorian factory workers of the Industrial Revolution faced such long, strenuous working hours that they faced a myriad of dangerous problems after they presumably collapsed into a chair at the end of their shifts.

According to one cotton mill worker laboring in the 1830s, it was once common for adults to work just over 70 hours in a week. Legislative reform knocked those hours down to 60-some hours per week. However, the reforms still left much to be desired because children under 13 could only work 48 hours a week in the mill, leaving the slack to be picked up by adults.

Sounds miserable, but could it have been deadly? It certainly is in the modern era. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), overly long work hours today have led to hundreds of thousands of deaths from complications such as stroke and heart disease. With less advanced medical care (and certainly less time to even see a doctor in the first place), we can't imagine it was much better for the average Victorian factory worker.

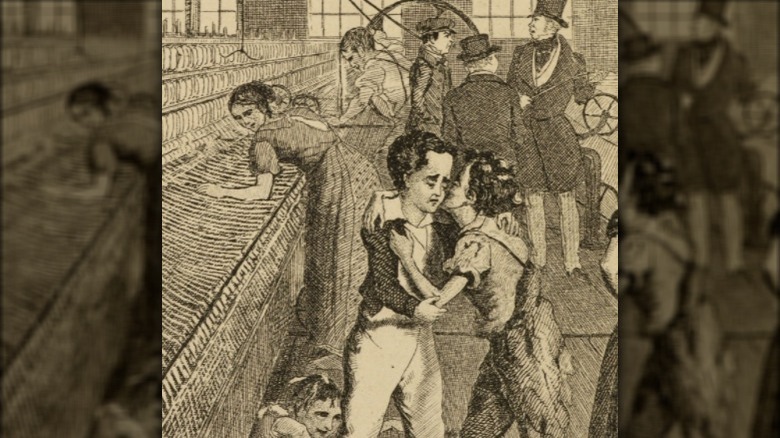

Child labor put kids in peril

As the National Archives reports, children caught up in the factories of the Industrial Revolution were subject to punishing hours and harsh consequences for honest mistakes that any primary school-aged kid might make. Only, they were making those sleep-deprived mistakes right next to early industrial equipment, meaning they risked losing limbs or even lives on a bad day.

The 1833 Factory Act attempted to address some of these deplorable conditions but did not do away with child labor completely. It forbade the employment of children younger than 9, but kids 9 to 13 still faced a nine-hour workday. Later acts were more in favor of working children, but progress was agonizingly slow. It wasn't until 1933, with the passage of the Children and Young Persons Act, that the majority of children under 14 were banned from working.

Why was child labor so prevalent in Victorian Britain? For one, it was cheap. According to History, children were typically paid paltry wages compared to adults, who themselves weren't compensated well to begin with. What's more, kids were physically smaller, meaning they could be sent into small spaces or be told to complete certain jobs that big, lumbering adults couldn't do — like crawling amongst dangerously whirling machinery. Oh, and emotionally immature children weren't expected to foment rebellion and form pesky unions, as adults sometimes did. All told, they were more easily forced into exploitative systems that put both their physical and mental health at risk.

Workers could experience deplorable living conditions

Now, to be entirely fair, the living conditions experienced by lower-class people in Victorian Britain were generally tough. While middle and upper-class folks enjoyed things like windows and indoor plumbing, says the National Archives, the poor often had to contend with dark, squalid homes just outside open sewers. Factory owners at least built homes for many of their workers, though budget-minded as they were, these planned communities weren't always much better than the slums that sprang up elsewhere.

According to the Industrial Archaeology Review, factory housing typically took one of two forms: through houses, in which inhabitants had access to both the front and back spaces of their respective quarters, and back-to-back housing, in which the rear of their homes turned out into a shared alley or courtyard. Back-to-back conditions were deemed especially deleterious to workers' health, given the lack of proper ventilation when the rear of the homes all faced one another. Meanwhile, other local features like common water pumps and outhouses, used by many residents of the neighborhood, contributed to the spread of diseases like cholera.

As per the National Archives, mortality rates for the poor living in these conditions showed that workers living in factory towns faced a particularly grim outlook. The environmental effects of the factories, including the large quantities of smoke pouring out of coal-fired industrial setups, made things all the worse.

Factory laborers were chronically stressed

As you may have already gathered, life as a factory worker during most of the Industrial Revolution was an unenviable lot. But while it's easy enough to point to concrete issues like open sewers and long hours, there was a more pernicious force at work: stress.

While there's no denying that cholera and missing limbs are a serious bummer, the psychological effects of stress could seriously impact workers' health. After all, with 60 to 70-hour work weeks and filthy, disease-ridden neighborhoods, how could anyone properly relax when they finally got some time off? And it's certainly not as if people were planning yearly trips to Disney World with their meager wages. Indeed, the idea of vacation must have seemed laughable to the factory workers of the Victorian era.

Not only were workers subject to punishing hours, but their work was stultifying, says "The Industrial Revolution in World History." Their intense yet boring work left little time for people to live their lives, much less organize against the difficult conditions and exploitative factory owners. And when they did have time, workers found that their towns lacked any real entertainment. Oftentimes, the most popular and accessible leisure activity was drinking, which hardly could have done much to alleviate the long-term links between chronic stress and mortality (via Cardiology).

Malnourishment was a serious issue

Long hours and tough conditions were already difficult for factory workers to manage. But then things got worse — they had to go home and choke down dinner.

That's because poor nutrition and downright depressing meals were the norms for quite a few factory workers throughout the Victorian era. The 1832 volume succinctly titled "The Moral and Physical Condition of the Working Classes Employed in the Cotton Manufacture in Manchester" describes some of these meager meals, which included a breakfast of bread and tea (after about three hours of working on a presumably empty stomach). Shamefully, the tea itself was pretty weak and may have only been graced with the barest amount of milk. Dinner was often boiled potatoes, sometimes livened up with a few scattered bits of meat. The fancy folks might whip up some plain oatmeal, too.

Now, as the journal Past & Present notes, it's not entirely fair to judge Victorian ways of life by our modern standards. Victorian reformers had an agenda that could very well have exaggerated these reports. Yet, surely we can agree that malnutrition and monotonous diets with scanty protein sources don't exactly encourage good health. According to Clinical Medicine, malnutrition affects a variety of bodily systems, from digestion to immune responses. It also apparently decreases cognitive function long-term for children (via JAMA Pediatrics). People who don't get enough decent-quality food, such as Victorian factory workers, are simply more likely to succumb to illnesses and work accidents.

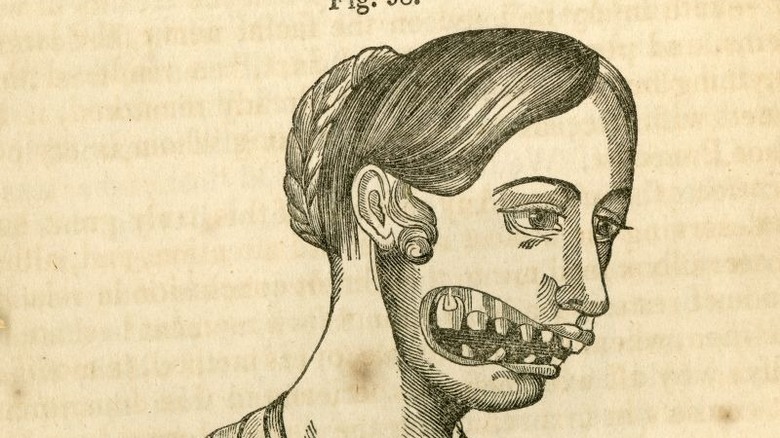

Exposure to phosphorus produced grisly effects

The grisly condition that came to be known as "phossy jaw" all started with matchsticks. According to the Royal College of Surgeons of England, Victorian manufacturers discovered that adding a particular type of white phosphorus to the ignition end of a matchstick made it easier to light. Strike-anywhere matches soon became a pretty big business, and factories full of workers coming into close daily contact with white phosphorus sprang up across Britain.

Over time, it became clear that phosphorus was pretty bad stuff, at least where jaws were concerned. Workers exposed to it would develop painful abscesses and necrotic tissue. Some were even forced to submit to surgery to have most or all of their jaw removed or face death otherwise. It got so bad that, by the 1880s, workers protested against the use of white phosphorus.

The matchstick girls' strike of 1888 saw many poor working women in London's East End protest against the continued use of white phosphorus, even though researchers and advocates had been documenting its effects for decades. As per The Conversation, the estimated 1,400 women and girls involved in the action were also protesting squalid living conditions, low pay, and punitive policies like fining a worker for the infraction of talking to someone next to her. Even so, it took until 1906 for white phosphorus to be banned in matchsticks.

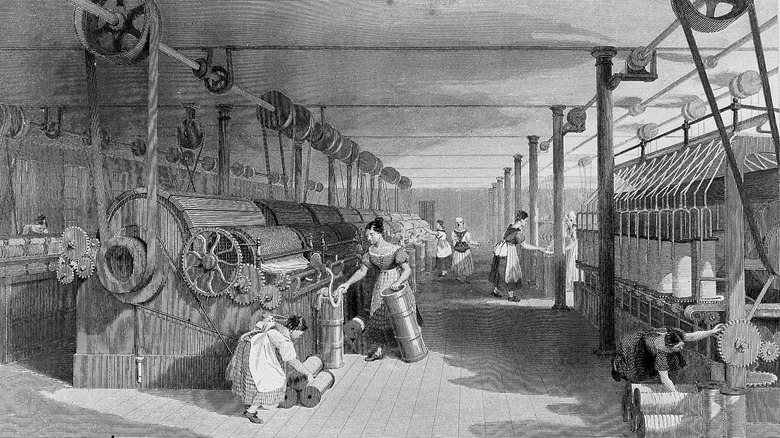

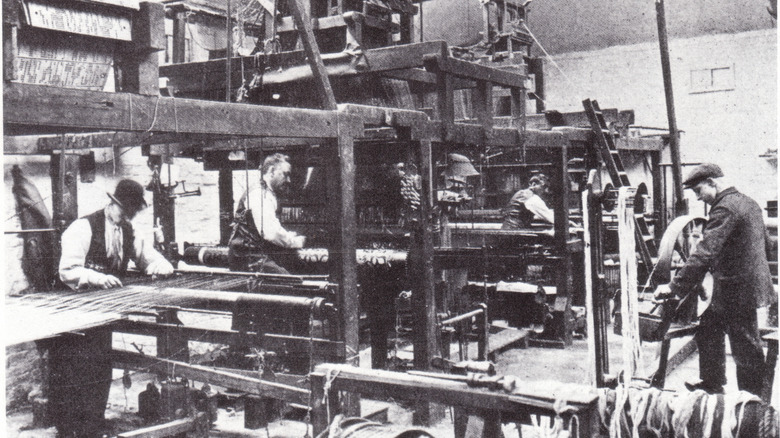

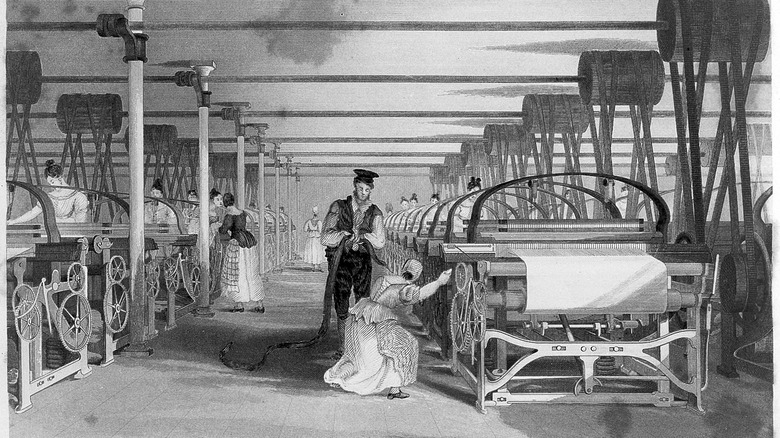

Victorian mills contained dangerous machines

In the rush to produce goods and reap the financial rewards, Victorian manufacturers were dangerously negligent when it came to worker safety. Things like guards or covers over moving parts were rare, and indeed some of the smallest workers were sent into the depths of these whirring, clacking death traps just to keep things moving at a lucrative pace.

That last job would belong to the mule scavenger. According to "The Worst Jobs in History," this role required children to plunge beneath the workings of weaving machines known as "mules." There, they swept up the accumulated bits of cotton before the fluff could gum up the works and stop production. The catch was that the machines weren't turned off. What's more, they had practically no fail-safes if the children scurrying beneath the machines got themselves into an awkward spot. If child laborers didn't move quickly enough or weren't scrupulously cautious (as few 8-year-olds are during 12 to 14-hours shifts in a humid, stifling factory), they could be crushed against the machinery.

Robert Blincoe, who was a former child laborer, described a particularly gruesome accident he claimed to have witnessed in his popular autobiography, "A Memoir of Robert Blincoe." In it, a young woman's apron was caught up in machinery and, in the span of a few seconds, she was irreversibly maimed. Yet, she somehow survived and, most grimly of all, was forced to return to work on crutches, even though she was forevermore crippled.

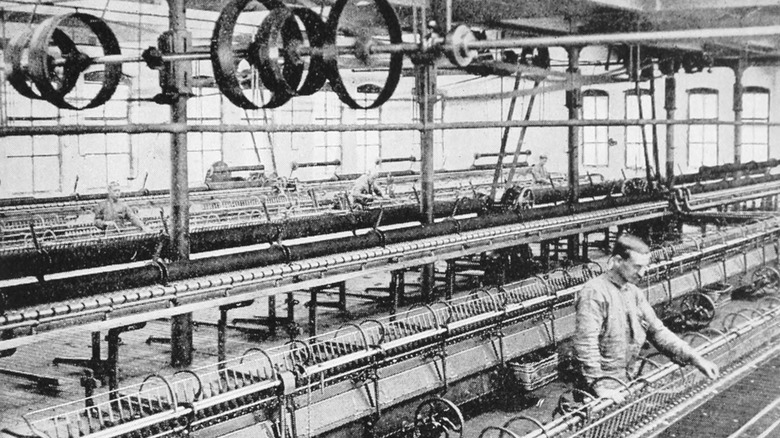

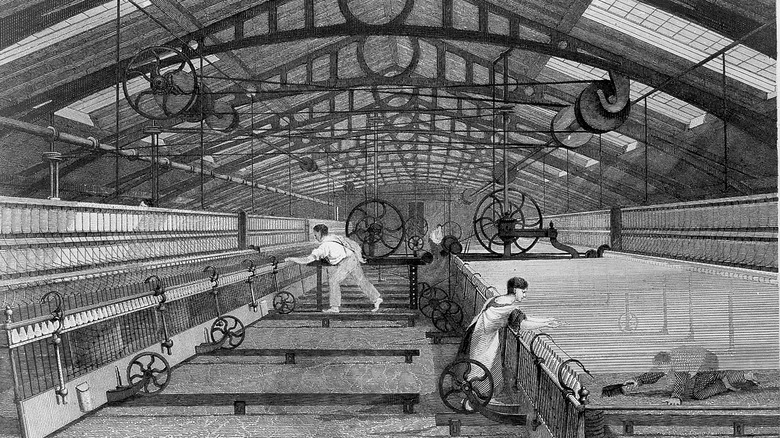

Textile workers suffered from a specific lung disease

As the mule scavengers could already tell you, cotton spinning produced a lot of stray fiber. And even if you weren't obliged to dodge heavy machinery to sweep it all away, that cotton fluff floating everywhere could still be deadly dangerous.

How could that be? Well, it's your fault for having lungs. According to "Victorian Technology," cotton mill workers were susceptible to a disease commonly known as byssinosis or brown lung. The condition occurs when textile workers inhale fine particles of non-synthetic fiber, such as cotton (via StatPearls). Common symptoms can include persistent coughing, difficulty breathing, and tightness in the chest. Continual exposure can make byssinosis persistent and can result in long-lasting damage to one's lung tissue. It's an issue in poorly regulated factories today and one that could potentially lead to fatal consequences if left untreated in the long term.

For Victorian factory workers, who could hardly afford to take an extended leave of absence to let their lungs recover, much less ask for respiratory protective equipment that didn't yet exist, it was all but inevitable that they would end up struggling to breathe.

The Industrial Revolution made laborers dangerously sleep-deprived

As any new parent or college freshman with an early morning class will tell you, sleep is pretty important. Indeed, you only truly appreciate sleep when you can't get it. That's sure all the more true when you're surrounded by open machinery in an exploitative workplace long before the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) was even a twinkle in some activists' eyes.

According to the journal Interface Focus, poor sleep was a serious issue for the Victorian working class. In fact, it was apparently an issue for all classes, as even prime minister William Gladstone reported on his own insomnia. But, while Gladstone might embarrass himself by nodding off in a meeting, he wasn't liable to lose a hand while doing so. Neither was he obliged to work more than 12 hours a day in front of dangerous machinery. Today, public health and safety organizations like the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recognize that sleep is vital to maintaining workplace safety. Ignoring could result in serious workplace accidents and even death.

Cruelly enough, the Victorians seemed to think that sleeplessness was only a problem of the upper classes. The Conversation reports that many people of the era assumed that insomnia came from overwork of the intellect and therefore afflicted only "brain-workers" and schoolchildren, not uneducated manual laborers.

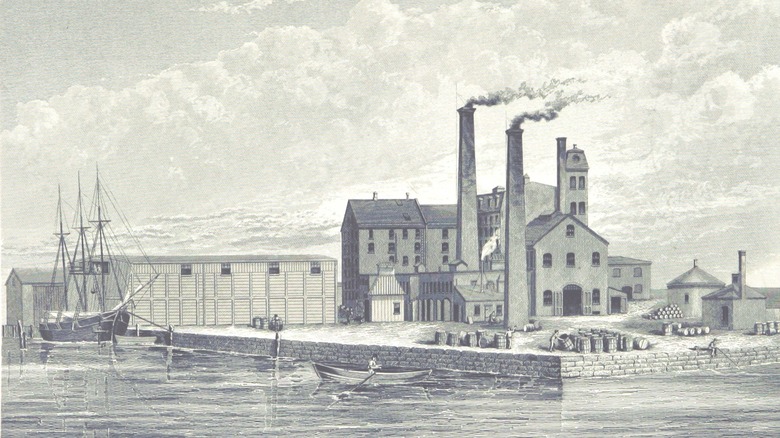

Factories belched out serious pollution

Even if you somehow managed to escape the punishing grind of working in a factory yourself, that plum job sitting at a desk somewhere wasn't enough to get you out of the factory's deadly shadow. That's because the pollution and industrial waste generated by these operations were sure to affect everyone in the area. London's air quality was strikingly bad during the 19th century, thanks to suspended particulate matter hanging in the smoggy air. All of that pollution had a clear effect on the respiratory and cardiovascular health of many unfortunates in the city (via Our World in Data).

Truth be told, the pollution of the Industrial Revolution had serious consequences that went far beyond the lands right around individual factories. According to Nature, climate scientists have found that temperatures had already begun to climb to unnatural levels by the middle of the 19th century. The culprit? While there aren't perfectly accurate instrument readings from that era, it's all but certain to have been greenhouse gases produced by the many, many factories operating across the globe. And as the World Health Organization (WHO) reports, climate change has had and will continue to present serious and even deadly health consequences.

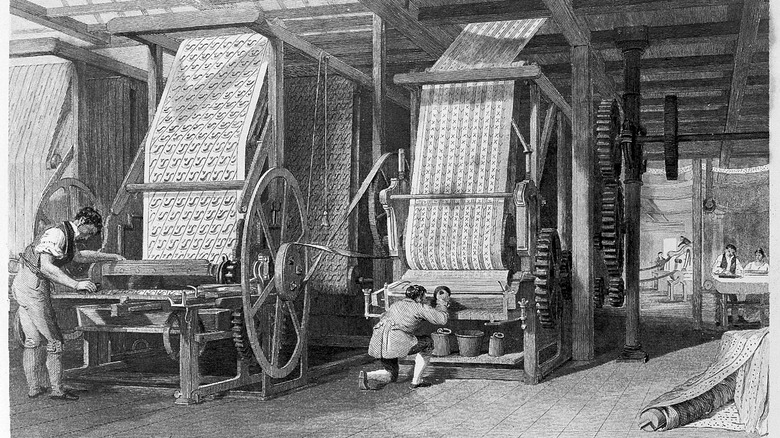

Factory workers could get caught up in violent protests

With all of the deadly risks associated with factory work, compounded with rampant classism, sexism, and terrible pay, it's no wonder that Victorian workers got seriously fed up. Some, like the East End matchstick girls of 1888, demonstrated in fairly peaceful protests. But, for others, the situation called for more dramatic and occasionally even deadly action. Enter the Luddites.

Today, a Luddite is often taken to mean someone who is broadly anti-technology. But while now that may apply to your fuddy-duddy relatives who somehow still don't know how to open an email, it had a far more intense meaning for the Victorians. Then, Luddites were actually protesting against increased mechanization, which was putting some weavers out of work. Their response? Smash the machines. Also, send threatening letters and physically attack those deemed responsible, such as factory owners (via National Archives).

It may have seemed like a good idea at the time, but the combined forces of market capitalism and the government soon squashed the rebellion. According to History, the protesters' violence got so bad that damaging factory equipment was made a capital offense. And in April 1812, some Luddites were even killed while striking a mill. The army eventually called in a few thousand soldiers to deal with the uprising. Following that, a few more of the recalcitrant workers were hanged or transported to the Australian colonies. By the next year, the Luddites had been more or less eradicated.