Will The Earth Ever Run Out Of Oil?

Oil and its byproducts are an essential part of the modern world we live in. It underpins nearly every aspect of our transportation infrastructure and is the very essence of so many of our modern conveniences.

A large part of its value comes from its versatility. For an idea of how versatile it is, let's just take a look at how oil — or more properly, petroleum — is used in cars. Obviously it's the basis for the gasoline (both diesel and unleaded) that propels them but it's also used to make the seat upholstery, the dashboard, and the speakers. And that's just the cosmetic stuff. Under the hood you've got fan belts, the battery box, bearing grease, and motor oil (via Ranken Energy).

It's no understatement to say that oil is foundational to our way of life, whether we know it or not. Petroleum is so vital to how we live our lives that it's almost impossible to think about living without it. But there isn't a limitless supply of oil and other fossil fuels. Someday we will run out. It's not a question of if, but when.

How much do we use?

One part of the answer to when the world will run out of oil lies in how much oil the world uses. That number — measured in barrels per day — fluctuates from year to year for a number of reasons. Most recently, the global pandemic caused a sharp drop in oil demand (and therefore consumption). In spring 2020, for example, the global demand in oil dropped by over 15% from winter 2019 due to the reduction in airline and road travel.

Oil consumption has recovered since the shock of the pandemic. The International Energy Agency estimates that worldwide demand for oil will be about 100 million barrels per day for the next few years. In the U.S., most of those barrels (65%) will be refined into unleaded and diesel gasoline for use in our cars, trucks and buses. The remaining 35% is divided between natural gasses, aviation fuel, asphalt, plastics, and lubricants.

How much do we have?

There are a few different ways to think about how much oil we have. One method is proved reserves. Basically, this is petroleum you think you can get out of the ground at a reasonable price, not how much you think is there. If the price of oil gets too low, worldwide proved reserves will also go down, because some oil will cost more to recover than can be recouped by selling it (via U.S. Energy Information Administration).

Another useful way of looking at it is in terms of technically recoverable reserves. Proved reserves looks at how much oil it's feasible to extract. The other side of that coin is unproved reserves: oil that could be extracted, but it doesn't make sense to do so at that time. The combination of proved and unproved reserves are considered technically recoverable reserves (via EIA).

According to BP's estimates, there were over 1.7 trillion barrels of proved reserves worldwide in 2020. There are thought to be around 3 trillion barrels of unproved reserves so that means that there are well over 4 trillion barrels that are technically recoverable (per Penn State University). Given 100 million barrels per day of consumption and 4.7 trillion barrels available, that gives us 47,000 days of oil, or over 128 years at our current rate of use. And that's assuming that it will be economically worthwhile to extract it.

Where does oil come from?

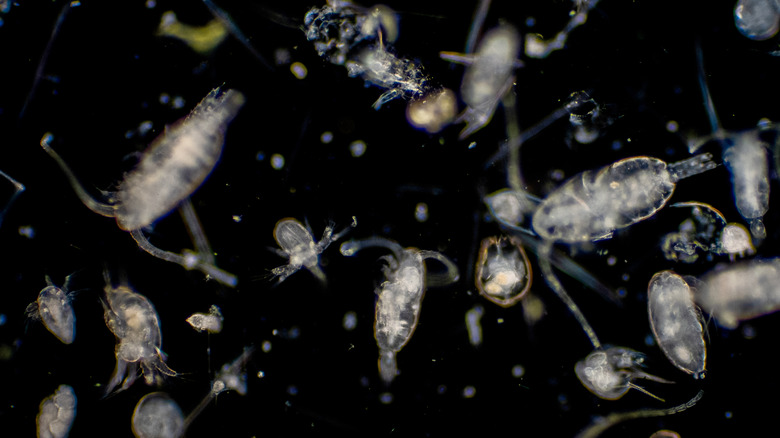

Petroleum, like all fossil fuels, is made from organic matter: stuff that used to be alive. Whereas coal is made primarily from plant matter, petroleum is made of mostly animals; in this case plankton. The higher ratio of proteins and fats are what drives its decomposition towards oil instead of coal (via Penn State University).

After these tiny sea creatures die they sink to become part of the sediment of the sea floor. As more sediment continues to be deposited over millions of years, the organic matter is subjected to increasing pressure and heat that transforms the organic sediment into bitumen (natural asphalt) and a substance called kerogen. As depth, pressure, and heat continue to rise, the kerogen is broken down into petroleum and natural gas (via PSU).

Contrary to simple intuition, the oil and gas don't exist in vast underground reservoirs. The earth's crust is mostly solid rock. Some of those rocks are porous and after millions of years have become saturated with water, oil, and gas. Because the fossil fuels are lighter than water, they rise to the top of these porous rocks until they reach the surface or are trapped beneath a non-porous rock layer.

History of oil extraction

Humans have been using oil for thousands of years. Herodotus writes how the walls of Babylon were constructed using bitumen, a super-viscous form of oil. Around the fourth century A.D, the first oil wells were being drilled in China using iron drill bits and bamboo pipe (via Recorder). These early wells were a byproduct of the search for brine but the Chinese people found many uses for the oil, from ink to medicine (via Historylines).

As early as the 9th century the process of distillation had been discovered in Persia by Abu Bakr al-Razi which was used to make kerosene (via 1001 Inventions). In 1848, Scottish scientist James Young brought the distillation process into the modern age by turning it into a successful commercial enterprise (via Historic UK).

Just over a decade later the world's first profitable oil well was drilled in Pennsylvania. Most of the major oil companies that exist today were formed in the wake of the oil boom that followed the well in Pennsylvania (via Offshore Technology).

The future of oil

It's impossible to predict with any certainty the future of oil. Too much depends on the whims of consumers and governments. If consumers behave as economists expect, for example, electric car demand will offset oil demand by over 20 million barrels per day in the next 25 years. Of course, if there is a prolonged oil price spike, it's likely people will jump on the electric car bandwagon sooner (via International Monetary Fund).

And it's just as hard to predict the price of oil. It's considered one of the most volatile commodities being traded. In addition to being subject to the classic laws of supply and demand, the price of oil is very sensitive to market speculation. If traders even think there could be a disruption in the oil supply due to war or natural disaster, prices of crude oil and its derivatives like gasoline will go up (via The Balance).

Ultimately, as consumers, we can only wait and see what will happen. Barring that, you can either make your voice heard by buying a Tesla or by cruising down the strip rolling coal.