The Untold Truth Of Azazel From The Bible

Naturally, the most famous demon in all of the Bible is Satan, whose scant few appearances as the tormentor of Job in the Hebrew Bible and the tempter of Jesus in the New Testament nevertheless managed to explode into a role as the Prince of Darkness and God's evil opposite. But while there are a number of unnamed demons throughout the biblical canon, very few names get applied to them, and those that do tend to refer to Satan, which itself is a job title rather than a personal name.

But one named figure -– if you choose to believe that he is a demon -– is the goat man of the desert, Azazel. His name appears as part of a mysterious rite of purification in the Hebrew Bible before being applied to all manner of demons, satyrs, and fallen angels. But to some people, the name might just refer to a goat or a treacherous stretch of land. So just what is the deal with Azazel anyway?

Azazel was the original scapegoat

The name Azazel only occurs one time in all of the canonical Bible, in Leviticus 16:8-10. As the Catholic Encyclopedia records, this passage explains the ceremony that the Jewish people should perform as part of Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement. The text says that Aaron (Moses' brother and the first high priest) should cast lots -– essentially draw straws -– over two goats, "one lot for the Lord and the other lot for Azazel." The goat on whom the Lord's lot fell would be sacrificed as an offering to God, while the goat marked for Azazel would be sent out into the wilderness to make atonement for the people. According to the Encyclopedia Judaica, the goat for Azazel was not a sacrifice, as it was not slaughtered. Instead, this living goat was meant to be a vessel for the sins of the community, which were carried off into the wilderness, thus cleansing the community of their sins. (Needless to say, this ceremony is not part of modern Yom Kippur services.)

As the Online Etymology Dictionary explains, this passage is the origin of the English term "scapegoat." This goat that became the symbolic bearer of the people's sins and then ran off into the wilderness — a literal "escape" goat — came to mean a person or thing blamed for the wrongdoings of others in modern parlance.

No one knows who or what Azazel is

Okay, so part of the expiation of sins for a community was sending out a goat for Azazel on the Day of Atonement. Great, no problem there, except: who or what is Azazel? The unsatisfying answer to that is that nobody really knows. As the Jewish Encyclopedia explains, the name Azazel itself is frustratingly obscure. Some rabbis interpreted the name as deriving from words that mean "rugged" and "strong," which they understood to represent the rugged cliffs down which the Azazel goat was sent. The Online Etymology Dictionary says that others read "Azazel" as "ez ozel," or "goat that departs," leading to the term being translated as "caper emissarius" ("goat that is sent out") in the Latin Vulgate Bible. Following this lead, some English translators render "for Azazel" as "a scapegoat."

A comparison of different English translations shows various interpretations of this tricky phrase: "for the scapegoat," "for an uninhabitable place," and a number that treat it as a proper name, simply saying "for Azazel." While for some translators this may simply be because they find the mysterious term untranslatable, for others it is a clear statement of intent: Azazel isn't a place or a goat, it's the entity receiving the goat. The Contemporary English Version makes no bones about exactly how they interpret this: "one will be sent into the desert to the demon Azazel."

Maybe Azazel was just a demon who ate goats

In the end, despite the efforts of modern translators and commentators (especially religious ones who might chafe at such an idea), it seems most likely that the obscure word Azazel simply refers to a demon who lived in the desert and once a year ate a goat that had been ritually stuffed with all the Jews' sins. It is perhaps important, however, to stress that even if Azazel is a supernatural being, he wasn't a deity, just a demon. The Jewish Encyclopedia points out that sending a goat out to a wilderness demon was a symbolic act of a community sending their sins and impurities out into the untamed wilderness, the metaphorical source of their sins and impurities.

The desert, a place of desolation and ruin, represented the source of impurity. Azazel, then, as the ruler of that waste, becomes not a god, but rather a personification of evil and wickedness. You might be asking yourself, "Isn't that what Satan is?" to which the answer is that Azazel comes earlier than the development of Satan in Jewish theology. As a personification of evil, the Jewish Encyclopedia refers to Azazel as "in some degree a preparation" for the idea of Satan. The figure of Azazel is likely pre-Israelite in origin and is probably closely tied to a communal fear for the mountainous desert region that he came to personify.

The Bible has a surprising number of goat demons

It might surprise you to hear that there's a goat demon in the Bible, even if you grew up learning Bible stories. As it turns out, there are actually quite a few goat demons spread throughout the Hebrew Bible, they're just hidden from you by the English translation. The Jewish Encyclopedia says that the Bible mentions two different types of demons in canonical text: the shedim and the se'irim. The shedim are more like the kind of demons you would typically imagine, spreading pestilence and misfortune over those unlucky enough to draw their attention.

The other class of demon, the se'irim, are a race of hairy goat-demons, similar to Greco-Roman satyrs and fauns. Their name literally means "hairy beings" and is related to the word for goat in Hebrew. Leviticus chapter 17, the chapter just before the one about Azazel's goat, includes a prohibition against the Israelites offering sacrifices to the se'irim. When the prophet Isaiah foretells the destruction of Babylon, he says goat-demons will dance in the ruins, which will provide a resting place for them and Lilith, the mother of demons. While some translations commit to the se'irim being satyrs or goat demons, others call them wild goats (and call Lilith a screech owl). As the Jewish Encyclopedia says, Azazel was most likely the chief of this race of ruin-inhabiting hairy goat boys.

Azazel led women to sin by inventing makeup

By the time of the Second Temple in Jerusalem following the captivity of the Jews by the Babylonians, exposure to Babylonian and Persian religion had influenced Jewish theology, leading to advancements in angelology and demonology, represented heavily in works like the apocryphal Second Temple-era Book of Enoch. As the Encyclopedia Judaica explains, the early portions of the Book of Enoch serve as an expanded retelling of the episode of the Sons of God and Daughters of Men from Genesis chapter 6. The author of this portion of Enoch interpreted "Sons of God" in this context to mean the Watchers, fallen angels who got mad lusty after some human women and came down from Heaven to woo them.

While the leader of these fallen angels is Samael, Azazel, formerly a lonely desert goat boy, gets upgraded to full dark angel status in this work. Chapter 8 of Enoch, which enumerates the evil skills taught to the previously innocent humankind by the celestial beings, names Azazel as the one who taught humans how to make swords, armor, and other weapons. But his knowledge of metallurgy went beyond simple killing machines: he taught women how to make jewelry and makeup, including specifically "beautifying the eyelids," which was considered both deceptive and the cause for fornication. The demon Azazel is the reprehensible monster responsible for both mass warfare and cosmetic MLMs.

Azazel's rocky fate

Fortunately for humanity, the fallen angels of the Book of Enoch will not be allowed to prosper with impunity for their corruption of mankind. Besides the fact that the sins of the Watchers and their hideous hybrid angel/human offspring, the cannibalistic giant Nephilim, led directly to God's decision to flood the Earth (like in the Noah's Ark story), the Watchers themselves suffer punishments at the hands of God's most powerful angels. Chapter 10 of Enoch tells us that Azazel, forger of swords and blender of eyeshadows, will suffer "a severe sentence": the archangel Raphael will bind him hand and foot and drag him to the desert in a place called Dudael, then open up a pit filled with hard and jagged rocks and cast Azazel into the darkness there, where he will stay forever, never seeing the light of the sun again until the Day of Judgment, on which he will be cast into the eternal fires of Hell together with the other fallen angels.

The Encyclopedia Judaica argues that Azazel's fate at the hands of Raphael unquestionably identifies him as the biblical Azazel: they identify the wilderness of Dudael as Bet Hadudo, which they say is meant to either itself be or else recall the jagged cliffs down which the scapegoat was cast as an offering to Azazel in Leviticus.

Azazel and two buddies opposed the ascension of the Metatron

While the Book of Enoch is one of the best-known works of Jewish apocrypha, it is more properly known as 1 Enoch, because there are two other lesser-known works that follow similar themes that have been preserved in different languages. The book known as 3 Enoch is also called the Hebrew Enoch because that's the language it survives in. Like the other two works, 3 Enoch tells the story of the titular Enoch, Noah's great-grandfather, who was so righteous that he was taken up alive by God into Heaven. In 3 Enoch specifically, we are told that Enoch is transformed into a powerful supernatural being called the Metatron, a 72-winged, 365-eyed super-angel who sits at a little desk next to God's throne and gets called "the Lesser YHWH."

Not everyone is cool with this development, however. Chapter 4 of 3 Enoch shows us three hostile angels who oppose God's elevation of a mortal to a status greater than that of the celestial beings. These angels are named Uzza, Azza, and Azazel (here spelled Azzael, which happens sometimes). God ignores their pleas, however, as we learn in the next chapter that these same three angels were the ones who descended to Earth and taught humankind sorceries and corrupted an entire generation, causing God to remove his holy presence from the Earth.

Azazel appeared to Abraham as a bird (and then a snake)

An apocryphal work from probably the first or second century CE known as the Apocalypse of Abraham expands on the life of the biblical patriarch, giving more information on his childhood, his conversion to the worship of the God of the Bible, and finally, a tour through Heaven, very similar to the one Enoch receives in the books named after him. As the Jewish Encyclopedia explains, Azazel features in this work as well, again filling the role of a fallen angel. First Azazel, normally associated with goats, appears to Abraham in the form of an unclean bird, swooping down at the sacrifices Abraham has prepared for God, in an expansion of Genesis 15:11, which says Abraham had to shoo away birds of prey from his sacrificial animals. Speaking with a human voice, the bird Azazel tries to talk Abraham out of his devotion to God. Fortunately, Abraham's guardian angel Yahoel drives Azazel off, telling the fallen angel that the celestial garments that once belonged to him in Heaven have been re-gifted to Abraham.

Later in the text, it is revealed that Azazel was the serpent in the Garden of Eden, described as a "serpent in form, but having hands and feet like a man, and wings on its shoulders: six on the right side and six on the left." Azazel is condemned to Hell for sharing the secrets of Heaven on Earth and enticing Adam and Eve into sexual sin.

Azazel was Esau's guardian angel

In an essay on Chabad, Rabbi Jonathan Sacks talks about the mystery of Azazel and the scapegoat and how for centuries rabbis and scholars have attempted to decipher the meaning of this seemingly strange ritual. One conclusion that many commentators landed on was that two goats identical in appearance but destined for a different lot in life reminded them of the idea of twins, specifically the most famous pair of twins in the Bible, Jacob and Esau. There's more to the Esau-Azazel connection than simply each one being one of a pair, however. Esau is, like Azazel, closely tied in the biblical text with goats: Esau is explicitly called a hairy (sa'ir in Hebrew) man, which is closely related to the word for goat (se'ir) and goat demons (se'irim). Likewise, when Esau departs from the land of his fathers, he settles in a place called Seir. Esau's other name, Edom, which means red, has also been connected to the red thread that some commentaries say was placed on the scapegoat for Azazel.

While the Esau of the canonical Bible is a more nuanced figure who reconciles with his brother Jacob, the Esau of tradition and folklore is pretty straightforwardly evil. With this in mind, it's not hard to understand the idea that Azazel was the fallen guardian angel of Esau, who in tradition becomes the spirit of heathenism.

The demonic lord of goats

First published in 1818, Jacques Collin de Plancy's Dictionnaire Infernal ("Infernal Dictionary") was, as you might guess from the title, an attempt to catalog and define all known knowledge about demons and the denizens of Hell. As Atlas Obscura points out, this book is more than just a catalog of demons in the way that its source materials such as the 16th century Pseudomonarchia Daemonum or the 17th century Lesser Key of Solomon, both of which lay out detailed hierarchies of Hell. The 1926 edition of the book calls it a "universal library on the beings, characters, books, deeds, and causes which pertain to the manifestations and magic of trafficking with Hell." And one of the things that makes it stand out from other works of demonology more than any other are the illustrations by painter Louis Breton and engraver M. Jarrault. There are hundreds of vivid illustrations throughout the book, dozens of which depict specific demons.

One of those specific demons, naturally, is Azazel. The entry for him describes him as a demon of the second order and a guardian of goats. It then goes on to explain the expiatory ceremony of the two goats on Yom Kippur before noting that Azazel also appears by name in John Milton's Paradise Lost. The illustration depicts him with horns, a pitchfork, a banner, and, of course, a goat.

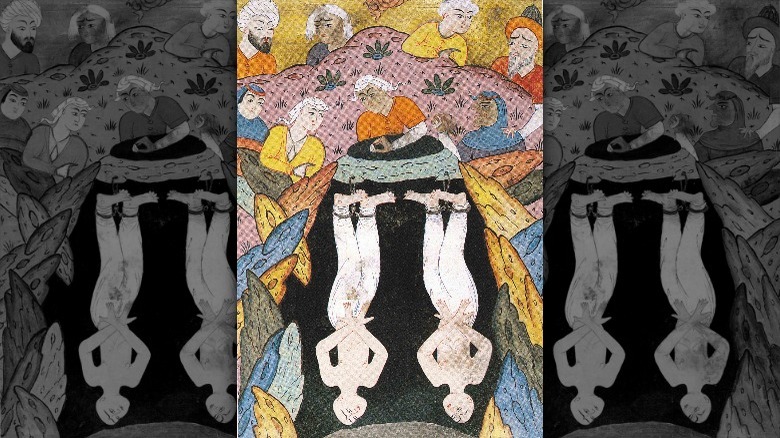

Azazel is a fallen angel in Islam

As the Jewish Encyclopedia explains, there is a story in Jewish legend that talks about the fall of the angels originating with Azazel and another angel named Samhazai. This story, with elements from traditions surrounding Uzza, Azza, and Azazel, was adapted into the Islamic tradition of the fallen angels Harut and Marut. According to the Encyclopedia Britannica, these two angels, whose names appear in the Quran as angels causing evil in Babylon, are said in Islamic mythology to have mocked humankind's weakness for its lapse into evil. When God challenges them that they would do no better when faced with temptation, they head to Earth and are immediately seduced by a beautiful woman (in the Jewish version, this is Noah's wife) and then immediately murder a witness to their sin.

The angels are forced to admit that God was right, and the punishment for the fallen angels is to hang by their feet in a well in Babylon until the Day of Judgment. In the Jewish version, only Samhazai repents and is punished by being suspended halfway between Heaven and Earth until Judgment Day, while Azazel retains his evil ways, becoming the little desert gremlin we see in Leviticus. Confusingly, in some Islamic traditions, Azazil is also said to have been the original name of Iblis, the chief of the devils, back when he was still head of all angels.

Azazel was at the center of the worst X-Men story ever

As a demon whose name actually appears in the Bible, it's probably not surprising that Azazel's name pops up a lot in popular culture as a demonic figure. He appears in video games, novels, and as the primary antagonist of the early seasons of "Supernatural." But he's also a central figure in a story that Comic Book Resources calls the worst X-Men story of all time. The story in question is "The Draco," which ran in Uncanny X-Men #428-434 starting in 2003, written by Chuck Austen and with art by Sean Phillips, Phillip Tan, and Takeshi Miyazawa.

By the time "The Draco" began, it had long been established that the X-Man Nightcrawler was the son of the shape-shifting mutant Mystique, but this story explains that his father was not the human Christian Wagner, but rather a mutant demon named Azazel, who comes from a Hell dimension and was the inspiration for legends of Satan. It turns out that Nightcrawler and a bunch of other mutants had been sired by Azazel in the hopes that they could use their teleportation powers to help him escape from the Hell dimension. By making Nightcrawler, whose devilish appearance belied his heroic and gentle demeanor, many fans felt making him a literal half-demon kind of ruined the metaphor. Nonetheless, despite being a much-hated character, Azazel managed to appear in a couple of X-Men movies.