The Millionaire Who Created A Baby Boom In 1920s Canada

What would you do for a chance to win nearly a million dollars? Would you endure humiliation? Would you push your body to its limits? Every person has their price, or at least that was the philosophy of old-timey millionaire, Charles Vance Millar. A lifelong bachelor, he suddenly died of a heart attack in 1926 with no one to inherit his large fortune. He had no close relatives or children.

What he did have was sharp wit and a special brand of wry humor. Millar secured his place in the prankster hall of fame by drawing up a last will and testament with some outrageous requests. He single-handedly caused a baby boom by promising his fortune to the mother who could have the most children in 10 years.

With that brief announcement following his funeral, the Great Toronto Stork Derby ushered in a decade of fervent baby-making. Only the most fertile of uteri could win.

Who was Charles Millar?

Charles Vance Millar was a Canadian born in 1854 to a family of farmers. He lived in poverty for many years before becoming a millionaire. As Maclean's details his story, in his early years after passing the bar, he only made about $3 a week from his first law firm. Millar struggled to get by until he was given a huge break by a hotel manager named McGaw, who essentially gave him free room and board. An added bonus, McGaw helped him establish his legal career by hiring him as the hotel's lawyer and referring guests to Millar.

Millar would become a highly successful lawyer and acquire additional wealth through several smart investments in real estate, horse racing, brewing, and transportation. He was also known for being frugal, and he never spent money unless there was a reason. Rather than pay a carpenter, he would spend hours after work at the law firm repairing the rental houses he owned in Toronto.

It was said that he had a shot at love once in his youth. Millar was in love with a young woman from one of Toronto's elite families. Unfortunately, her family did not approve of her marrying a low-earning son of a farmer.

Although his personal life was described as boring, Millar was also known for using his sharp intelligence for practical jokes. Maclean's reports that his favorite prank would be to leave money on the veranda of the Queen's Hotel, then hide and watch people's reactions (and how long it would take for them to pocket the cash). The fascination with people and money became the basis of the will that would make him posthumously famous.

His Last Will and Testament

When Charles Millar died he was given the typical treatment of mourners praising his life's accomplishments. The public was treated to something slightly more scandalous in the weeks following his death, with Millar's last will and testament providing a bit of a joke for all the public to witness.

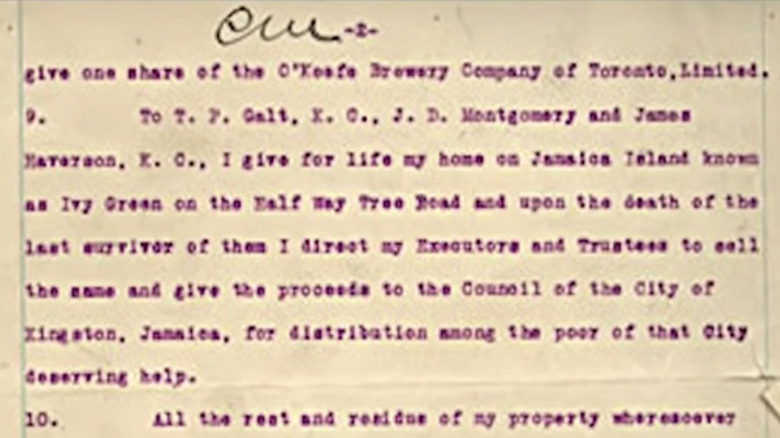

Three clauses in the will made some unusual requests. As Time reports, Millar had willed about $700,000 of stock in a brewery to a group of Methodist ministers who were against alcohol consumption and to see if "their avarice for money was greater than their principles." Keep in mind that this was the 1920s during the Prohibition Era, when America banned alcohol, and Canada was a bit spotty on the matter, as the Canadian Encyclopedia reports. Millar gave his stock in the Ontario Jockey Club to three opponents of horseracing, and also bequeathed a house in Jamaica to three lawyers who hated each other, as aw historian Lloyd Duhaime reports .

The clause that raised the most commotion in the public was clause nine. Duhaime reveals Millar offered the remainder of his fortune be liquidated "and at the expiration of ten years from my death to give it and its accumulations to the mother who has since my death given birth in Toronto to the greatest number of children." With the announcement circulating in local newspapers, the Great Toronto Stork Derby commenced.

The Stork Derby takes off

The baby race took place between 1926 and Halloween of 1936. According to FiveThirtyEight, it is unknown how many women participated in the event, but over the years newspapers reported on the mothers as they joined in and dropped out. News coverage truly took off with profiles around 1932, when there were but four years left on the clock.

After the Great Depression was in full swing there was a spike in participants, all of whom were hoping to escape poverty by winning. The publicity proved to be an easy way to earn some much-needed quick cash for these families, as a 1940s article in Good Housekeeping reports. Women would sign contracts with newspapers in exchange for money and exclusive appearances with their publications. Considering many women were living in squalid conditions or relying heavily on state relief, this was an easy way to make a quick honest dollar.

Many women back then understood their value as public figures in what was basically the pregnancy Olympics. Good Housekeeping wrote that one contestant, Lillian Kenny, was said to enjoy the publicity around her. She was also said to become upset if people took her photo without paying her for it, having once attacked a photographer for snapping a free photo.

Court battles over the Stork Derby

It might be hard to believe, but not everyone was amused by Charles Millar's practical joke. His distant family members tried to collect the fortune for themselves. According to Mark Orin, in his book "The Great Stork Derby," in 1927 six of Millar's cousins set about nullifying the infamous "clause nine," claiming the baby race was against public policy and encouraged immoral behavior. Millar's executors managed to get the case dropped, citing that the cousins, much like a half aunt who filed a case before them, were not entitled to the inheritance.

The court also found that the clause was not considered in violation of public policy. It did however clarify the language on who was eligible to win. According to the 1937 court record for the estate of Charles Millar, the judge agreed with a previous ruling that only legitimate-born children registered in the city of Toronto would be counted. This stipulation caused a major upset and would lead to a settlement being paid out later to two mothers who technically won.

Women were putting their health at risk to win

How did these women plan on maximizing their fertility efforts? During the Great Depression, women did not have the benefit of hormones and other pharmaceuticals to increase their fertility. Humans are not like factories, and a woman's womb cannot push out a fresh baby like an assembly line, so what options did parents in the 1930s have?

In those days, presumably people were aware of women's ovulation cycles, as fertility rates had dropped, according to FiveThirtyEight. Women in the race at least had a rudimentary means of planning for their next baby. Whether or not they were aware of it, they could have also weaned their babies early to increase their chances. However, early weaning is risky for both mother and baby. It can increase the risk of obesity and cancer, babies lose out on many benefits from breast milk, and it can increase their chances of sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS), as Verywell reports.

What about the frequency? Having multiple children with little rest in between could be deadly for some women. The baby derby was increasing women's risk of miscarriages, damaged uteri, premature birth, and anemia, among other serious conditions (via Mayo Clinic). According to the Mayo Clinic, these risks increase with the age of the mother and reports the ideal interval between pregnancies is 18 to 24 months.

This would mean that each participant would have had to be pregnant practically twice a year for 10 years, with live births, just to win.

A welcome distraction from the Great Depression

The Great Depression began in 1929, just three years into the Stork Derby, and Canada suffered almost as badly as America. Nearly 30% of Canadians were unemployed by 1933, and one in five came to rely on government relief programs (via the Canadian Encyclopedia). Newspaper articles from the era were often bleak.

Charles Millar's will achieved two things: It gave the families participating in the contest hope to get out of poverty, and for the rest of Toronto (and other parts of North America) it was a media circus that distracted from the dark times. Many people, including some of the contestants, lived in squalid conditions. One participant, Lillian Kenny, lost one of her children born during the race due to living in a rat-infested home. Time reports that Kenny's 1-year-old son had died after being bitten.

It also provided families with money from media appearances. During this era, the job opportunities gained after World War I steadily began to shrink. In the 1920s, women were starting to work in professional settings as librarians, clerical staff, and physiotherapists, according to the Canadian Encyclopedia. When the Depression hit, the first people laid off were women.

Newspaper coverage of the derby did not really start gaining traction until 1932, when Ontario's Supreme Court attempted to strike down the Millar will as unlawful, as per FiveThirtyEight. It is also suspected that more women became involved because they realized they were eligible due to their large families and the timing.

The Windsor-Detroit Tunnel plays a role

One of the busiest United States-Canadian border crossings is also connected to this story. Multiple attempts to build a tunnel connecting the two countries in the Great Lakes Region had previously failed due to poor location choices. But in comes Charles Millar, who owned land in the optimum location for what would eventually become the Detroit-Windsor Tunnel. The story goes that the land's value (100,000 shares worth) ballooned from the small sum Millar initially paid to $750,000 when it was liquidated (via "Ghost Road," by Marty Gervais) and made available to the winners.

Millar apparently made the investment out of sheer spite over a mishap with a ferry boat operation. He became angry after he missed a ferry boat once between the two cities and sought to make ferries obsolete with the tunnel, as Owlcation reveals.

Since its first opening in 1930, the Windsor-Detroit Tunnel facilitates more than 4 million vehicles per year and is the only international underwater automobile border crossing in the world (via the official Detroit-Windsor Tunnel website).

A brief look at the top contenders

According to "The Great Stork Race," by Mark Orkin, there were five mothers leading the charge in 1934: Lillian Kenny, Grace Bagnato, Florence Brown, Hilda Graziano, Emmanuela Darrigo, and Mrs. Clarence Kitts. By this point in the race, a rivalry had formed between Kenny and Bagnato –- complete with trash talk. For example, in a 1934 article with Time magazine, Kenny took a shot at Bagnato by saying, "I am determined to beat that Bagnato woman, if nothing else," and even criticized her age.

Bagnato was an Italian-Canadian immigrant who had become a respected minor public figure through her work as a court interpreter (via CBC Radio One). Bagnato would juggle motherhood, interpreting for the courts, and assisting members of her neighborhood. "The Great Stork Race" reports that she had seven children in the race by 1934, with 12 living children total.

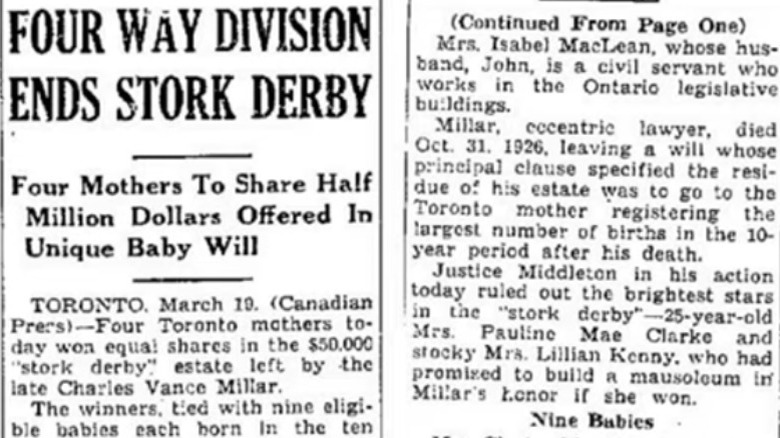

Kenny was a top contender, having claimed 11 eligible children by 1936. But she was dismissed because four of them had been stillborn, and she tried to have one of them registered as a twin birth, as Good Housekeeping reports. Kenny eventually brought a lawsuit and was given a settlement as a consolation prize.

Pauline Mae Clarke delivered 10 children as well, but she was disqualified on multiple counts. According to "The Great Stork Race," five of her children were found illegitimate, and a few of her legitimate children were not born within Toronto city limits.

Crowning the winners

The Great Toronto Stork Derby came to an end on Halloween 1936 at 4:30 p.m. — exactly 10 years to the minute from Charles Millar's death, as reported in "The Great Stork Derby," by Mark Orkin. A judge named William Middleton was in charge of determining who the winner was in 1936. His first task was to weed out the finalists by defining which families were eligible for the inheritance. Middleton determined only mothers who had given birth to live, legitimate children could win,

The judge ruled the earnings should be divided between Annie Katherine Smith, Kathleen Ellen Nagle, Lucy Alice Timleck, and Isabel Mary Maclean. Snopes reports they all had nine children during the 10-year contest and were rewarded with $125,000 each. Snopes also reports that two women in the race, Pauline Mae Clarke and Lillian Kenny, both received $12,500 but only after filing a lawsuit.

The other women received nothing, not a single dollar for their efforts. Grace Bagnato's granddaughter told CBC Radio One that she was so upset by her loss, that she nor her family ever spoke about her participation after the race ended. Her grandson, Charlie, suspects it was due to anti-Italian sentiments that were common during those days.

The winners spent their new fortunes sensibly — most of them bought large homes to accommodate their massive broods, but the Macleans also invested in bonds. Annie Kathrine Smith and her husband invested in a small hotel (via Good Housekeeping).

So was there a point of the contest?

Charles Millar was said to have believed that "every man has his price," and the will was a means to prove that pet theory. It has been said by his close friends the whole affair was an elaborate attempt to reveal how ridiculous people can be, as "The Great Stork Derby" reports.

A close friend of Millar's, Col. John Bruce said there was typically a point to his jokes, and "The Great Stork Derby" reveals that Millar despised people with "holier-than-thou" attitudes.

Bruce claimed Millar was an advocate of birth control since he saw the burden of excessive, unplanned children contributing to the poverty level and general difficulties of poor families. He hoped the fallout from mindless reproduction would force lawmakers to see the need for the legalization of contraceptives.

There is no true way of knowing the "why" behind the will or Millar's state of mind when he wrote it. Perhaps it was merely a quest he was leaving for his executors to discover if Millar was able to push the boundaries of the law.

Derby aftermath and criticism

There was no shortage of critics for the baby race, both during and after the money was dolled out. Many people have criticized Charles Millar's contest for driving people into a fertility frenzy. Famed feminist and birth-control advocate Margaret Sanger spoke out vehemently against it, and said that it was reducing women to animals (via "The Great Stork Derby").

It is unknown how many children, legitimate or otherwise, were produced as a result of the contest. According to Owlcation, at least two dozen mothers had produced some 190 babies between them. Outside of the winners, these families were left with nothing from the Stork Derby but extra mouths to feed.

Over the years residents of Toronto let memories of the baby derby fade into history. That was until it got the silver screen treatment. In 2002, a film about it was released starring Megan Fellows (via Globe and Mail). The names have been changed, but the film explores the hardships the derby mothers experienced (including the anti-immigrant sentiment felt by Grace Bagnato's character).

One last curious note about the baby race: Good Housekeeping reported in 1941, that not a single woman in the race named their child after Charles Vance Millar, except for Lillian Kenny in 1932. But sadly, that baby was stillborn.