The Untold Truth Of The World's First Person Executed By Electric Chair

When the electric chair was first invented, the term "electrocution" had yet to be created. Other terms that were thrown around as options included "electricide," "electromort," and "ampermort," but they didn't stand the test of time. But despite the fact that the electric chair was portrayed as a humane method of execution when it was introduced, there's been little evidence over the years to actually support this claim. Electrocution kills by disrupting a person's heartbeat, but because electrocution typically delivers more than one shock, this means that the electric chair often revives someone several times before finally killing them for good.

Meanwhile, a man named William Kemmler became the first person in the world to be killed with the electric chair in the late 19th century. Since then, there have been over 4,000 executions by electrocution in the United States alone, but many of them share the botched nature of the very first execution by electrocution.

It took almost 100 years after the first electrocution for the Supreme Court to review the constitutionality of electrocution, after they were inspired by over a dozen botched electrocutions in Florida. But while many states in the United States have since abandoned the use of the electric chair, in states like South Carolina, death row inmates are still offered the choice between the electric chair and a firing squad. This is the untold truth of the world's first person executed by electric chair.

Who was William Kemmler?

William Francis Kemmler was born on May 9, 1860, to German immigrant parents in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Kemmler left school by the age of 10 and worked a variety of jobs until he set himself up as an independent fruit and vegetable trader at the age of 19. Said to be illiterate, some reports also described Kemmler as intellectually disabled.

According to "Old Sparky" by Anthony Galvin, Kemmler began drinking whiskey as soon as he could afford to and quickly became a heavy drinker. It was reportedly after one particularly heavy bender that Kemmler woke up in Camden, New Jersey to find that he'd married Ida Forter. But after Kemmler realized that Forter hadn't even divorced her first husband, he left her and moved in with Matilda Ziegler upon returning to Philadelphia. Although Ziegler was also married, she'd reportedly left her husband because of his constant adultery and the fact that she'd contracted an STD as a result.

Kemmler and Zeigler ran off to Buffalo, New York in 1888 with Zeigler's four-year-old daughter. But in "The Electric Chair," Craig Brandon writes that the three of them didn't exactly experience domestic bliss together. Neighbors often heard loud and violent arguments coming from their apartment and reported that both were known to have violent tempers. "Some said they often heard blows being struck, but no one intervened."

Murdering Matilda

On March 29, 1889, things escalated irreversibly. William Kemmler reportedly seemed sober, according to his employees, but after Matilda Zeigler came out to ask him to get some eggs, instead of going to get eggs Kemmler picked up a hatchet and followed Zeigler inside. Galvin writes in "Old Sparky" that Kemmler then proceeded to hit Ziegler over 25 times with the hatchet as Zeigler's daughter watched.

According to "The Electric Chair," the neighbors reportedly heard screams and the sounds of fighting as early as 8 in the morning, but because such sounds occurred so often, the neighbors ignored them as they'd become accustomed to doing. But this time, things were different. This time, Kemmler came running into the kitchen of his neighbor Mary Reid, drunk and covered in blood, and admitted to Reid that he'd killed Ziegler, according to "The Electric War" by Mike Winchell. "I've killed her. I had to do it. There was no help for it. I'll hang for the deed. Either one of us had to die."

Ziegler somehow survived the initial attack, but she died several hours later at the hospital. Meanwhile, Kemmler repeatedly insisted that his temper was to blame and that he was better off being hanged as soon as possible. But although Kemmler would certainly be convicted and executed sooner rather than later, he didn't realize that he was about to become a human guinea pig for a new execution method.

The Electrical Execution Act

Less than one year before William Kemmler's murder of Matilda Zeigler, the state of New York passed the Electrical Execution Act, also known as the Electrocution Act, on June 4, 1888. Under this act, anyone sentenced to death after January 1, 1889 would be sentenced to electrocution instead of being hanged.

But according to Fordham Law School, because the act hadn't specified whether alternating currents (AC) or (direct currents) DC was going to be used, the Medico-Legal Society of New York was given the task of determining the current to be used. As a result, the use of electrocution as a method of execution also became caught up in what was known as the War of Currents.

In "Demands of the Dead," Katy Ryan writes that the decision to use electrocution instead of hanging was based on the idea that "the barbarity of capital punishment could be eliminated by adopting a new scientific method" and that these "human alternative[s]" could mitigate any public sympathy towards executed people.

'War of currents'

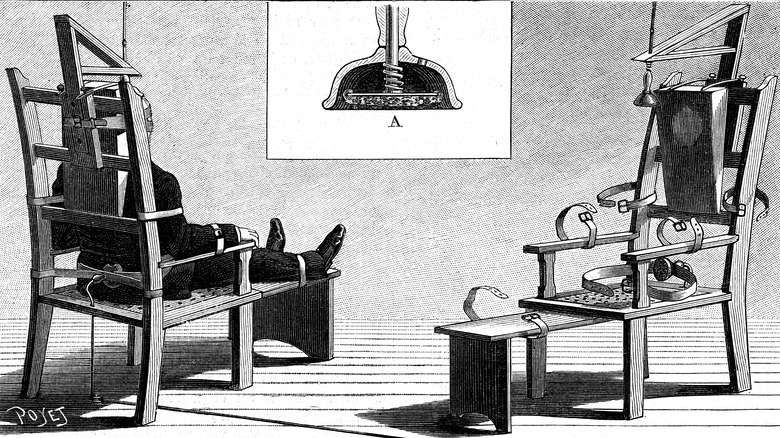

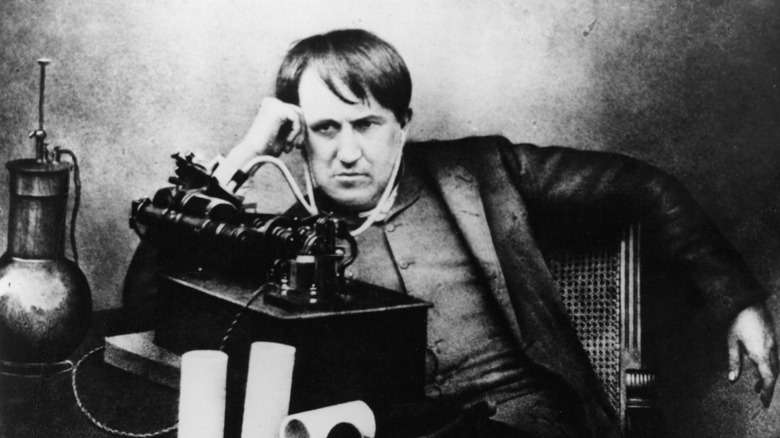

Thomas A. Edison and George Westinghouse battled over the execution of William Kemmler as part of the War of Currents for almost two years. While Westinghouse developed the use of AC for electric power distribution, Edison developed the use of DC and in order to maintain a monopoly on electrical power distribution contracts, he was determined to convince everyone of the danger of AC, according to "The Electric Chair." And after Governor David Hill passed the Electrical Execution Act, Edison did everything he could to ensure that the "dangerous" AC was involved in the execution.

According to "Profiles in Folly" by Alan Axelrod, Edison even commissioned Harold P. Brown to build the first-ever electric chair for New York's executions. Edison wanted the chair to be built with a Westinghouse AC generator, and even after Westinghouse refused to sell Brown the generator, Edison paid for Brown to acquire the generator through a university in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

Animal sacrifices

Thomas Edison claimed that the George Westinghouse generator was so dangerous that the state of New York had already specifically chosen it for electrocution because of AC's natural deadliness. Brandon writes in "The Electric Chair" that Westinghouse tried to convince people that even though AC used a higher voltage it wasn't any more dangerous than direct current, but few understood the details of volts and transformers. "When it came down to making a choice it was Edison's word against Westinghouse's."

But Edison was so intent on misinforming people about the so-called dangers of AC compared to DC that he was willing to do anything to convince people. According to "Elephants Under Human Care" by Paul A. Rees, this is why Edison staged a series of public electrocutions using animals like dogs and cats. He also started trying to popularize the term "westinghousing" to mean death by electrocution.

Thirteen years later, Edison also went on to use his own DC current to electrocute an elephant at Coney Island.

Appealing the execution

In response to Thomas Edison's campaign to install the AC generator as the poster child for electrocution, George Westinghouse tried to appeal William Kemmler's execution altogether. According to "The Electric Chair," Westinghouse hired W. Bourke Cochran, a prominent lawyer with political connections, to appeal the execution and argue that to kill someone with electricity would violate the Eighth Amendment by being a cruel and unusual punishment.

ABA Journal writes Westinghouse also challenged the use of animal experimentation in electrocution, something that Edison himself participated in numerous times. Westinghouse ended up spending up to $100,000 on legal fees, over $3 million in 2022, as the case went all the way to the Supreme Court in an attempt to make New York State execute people by hanging again.

Galvin writes in "Old Sparky" that Edison himself testified to the humaneness of electrocution as an execution method and claimed that as long as the electric shock was controlled, then "instant death would result without the distressing side effects."

Not cruel and unusual

After a lower court rejected the claim that electrocution was cruel and unusual, W. Bourke Cochran appealed once more, this time to the Supreme Court of New York. But ultimately, the Supreme Court didn't buy Cochran's arguments.

Although the Supreme Court of New York conceded that the use of electrocution was certainly unusual, the Supreme Court agreed with the lower court's decision and ruled that they couldn't definitively describe electrocution as cruel if the method had never been used before, according to The Electric Chair. In In re Kemmler, the Supreme Court also ruled that "the Eighth Amendment did not apply to the states and therefore left unexamined the New York state legislature's conclusion that electrocution produced 'instantaneous, and, therefore, painless death,'" writes Fordham Law School. According to the "Handbook of Death & Dying," the Supreme Court also ruled that the punishment of death is only cruel if it involves torture, but that execution is in itself not cruel. "It implies there is something inhumane and barbarous, something more than the mere extinguishment of life."

And even before the Supreme Court gave its ruling, Edison and Brown wasted no time in making sure the electric chair was wired up and ready to go at a moment's notice. In "Old Sparky," Galvin writes that Brown didn't even wait for the verdict before installing the first electric chair at Auburn Prison in New York.

A horse's electrocution

Cats and dogs weren't the only animals subjected to electrocution by humans. Cows and horses were also used in the electrocution trials of Thomas Edison and Harold Brown in their attempt to prove the functionality of electricity in executions.

On the day before William Kemmler's execution, Brown tested the first electric chair in preparation for the first human electrocution. Taking a "gaunt, worn-out horse," Brown electrocuted it in order to determine the number of volts it might take to execute a human by electrocution. In "Technologies of Life and Death," Kelly Oliver writes that Brown used 1,000 volts of AC on the horse, causing it to die immediately. Based on this, it was determined, according to The Electrical Review, that it would only take around 750 volts to execute Kemmler. Whether or not this measure was actually accurate would be determined the following day.

Deeming the horse's electrocution to have been, the electric chair was ready for its first human victim.

1,000 volts

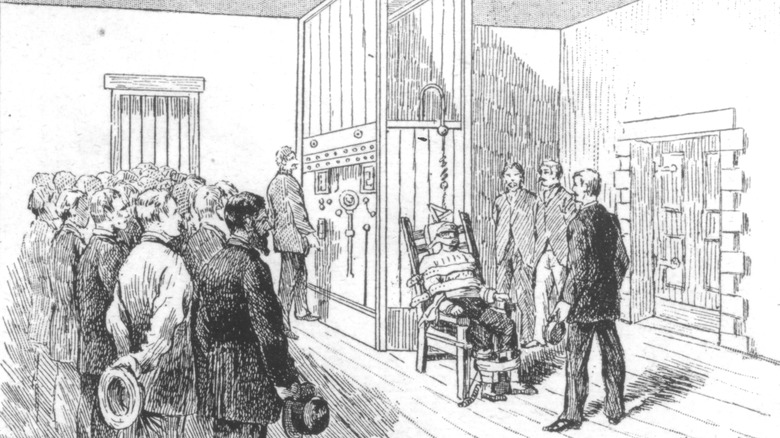

On August 6, 1890, William Kemmler was dressed in a suit and taken to the basement of Auburn prison, where the electric chair was set up. According to The New York Times, there were 25 witnesses there to watch the first execution by electrocution, 14 of whom were doctors there to evaluate the electrocution. "The proceedings seemed strangely casual as Kemmler took off his coat and sat in the chair after being introduced to the witnesses in the room."

After electrodes were attached to Kemmler's body and a black cloth was placed over his head, he was exposed to 17 seconds of 1,000 volts of electricity at 6:43 AM, Oliver writes in "Technologies of Life and Death," causing Kemmler to turn bright red and have a seizure. After 17 seconds, the current was turned off and the doctors pronounced him to be dead.

But within seconds Kemmler's groans showed that he was unfortunately very much alive. Although he remained unconscious, writes The Washington Post, his heart and lungs were clearly still working and his breathing was labored as he drooled. Although one doctor ordered another round of electricity, they had to wait several minutes for the generator to power up before they could deliver the second shock.

2,000 volts

Once the generator had powered up again, William Kemmler was subjected to another electric current, this time using 2,000 volts. "Technologies of Life and Death" writes that this second shock, which Kemmler was subjected to for over one minute, "caused his blood vessels to burst and his skin to catch fire." Some reports even claim that the second round of electrocution lasted over four minutes, according to The Washington Post. This second shock finally killed Kemmler as witnesses reported the smell of burnt flesh and hair accompanied by the sounds of crackling. George Westinghouse later reportedly remarked that "they would have done better using an ax," playing on the murder weapon used by Kemmler himself.

The scene was too much for some of the witnesses to bear. Some collapsed in the room while others, like the district attorney who'd prosecuted the case, ran out and collapsed in the hallway.

Three hours later, an autopsy was conducted, after which the doctors concluded that because Kemmler was rendered unconscious by the first electrical shock, he likely experienced no pain throughout the electrocution. They also claimed that even though Kemmler wasn't killed instantly, this was because of a faulty machine rather than any issue with the method of execution itself.

Public outrage

Although doctors tried to convince the public that the electrocution went off without a hitch, there was a great deal of public outrage following William Kemmler's execution. According to The New York Times, even Charles Huntley, an electrician who witnessed the execution, stated that "it was one of the most horrifying sights I have ever witnessed or expect to witness. There is no money that would tempt me to go through the business again."

The Washington Post reports that after news of the botched electrocution spread, many people rejected electrocution in favor of hanging. Others tried to use the incident to push for an overall ban on capital punishment. Dr. George F. Shrady, the editor of the Medical Record of New York, wrote an editorial that predicted that "public opinion will soon banish the death chair, as it has done the rope, and imprisonment for life will be the only proper punishment meted out to a murderer."

However, the "Handbook of Death & Dying" writes that not everyone was dismayed by this new method of electrocution. An article in Illustrated America insisted that "the first experiment in electrocution was not so horrible as many hangings have been" and Dr. Alfred P. Southwick, inventor of the electric chair, claimed that "a party of ladies could sit in a room where an execution of this kind was going on and not see anything repulsive whatsoever."

Executed twice

Although William Kemmler's execution was the first state-sanctioned death by electrocution, it certainly wouldn't be the last. And unfortunately, many of the electrocutions followed the botched nature of Kemmler's electrocution. Financial Review reports that botched electrocutions were so common that they were considered to be the norm and even electrocutions that went according to plan "were still brutal, brutalizing events."

One of the most famous botched executions involving electrocution was the execution of teenager Willie Francis in 1946. According to "The Death Penalty as Cruel Treatment and Torture" by William A. Schabas, Francis was first electrocuted on May 3, 1946, but because the two executioners were drunk when they were setting up the chair, the chair failed to provide a lethal shock. Francis ended up surviving a shock of 2,500 volts. And although he was scheduled to be executed again the following week, his case ended up going to the Supreme Court as attorney Bertrand DeBlanc argued that "it's not humane to make a man go to the chair twice," Face2Face Africa reports.

However, the Supreme Court ruled against Francis, and almost a year to the day after the first attempted execution, Francis was once again subjected to the electric chair on May 9, 1947. This time, the chair was properly set up and after five minutes of electrocution, Francis was pronounced dead, forever known as "the teenager who was executed twice."