A Successful Eye Transplant Has Never Been Performed. Here's Why

Back in the 1800s, scientists began attempting to transplant eyes in research animals in an attempt to restore sight or improve vision for people with impairments due to eye injuries, according to STAT News. Like some hodgepodge Frankenstein project, early scientists tried out various combinations of eye donors and recipients in the laboratory, from dogs to rats to sheep. But because of a delicate and intricate network of muscles, blood vessels, and nerves that are literally connected straight to the brain, these experiments all failed, per STAT News.

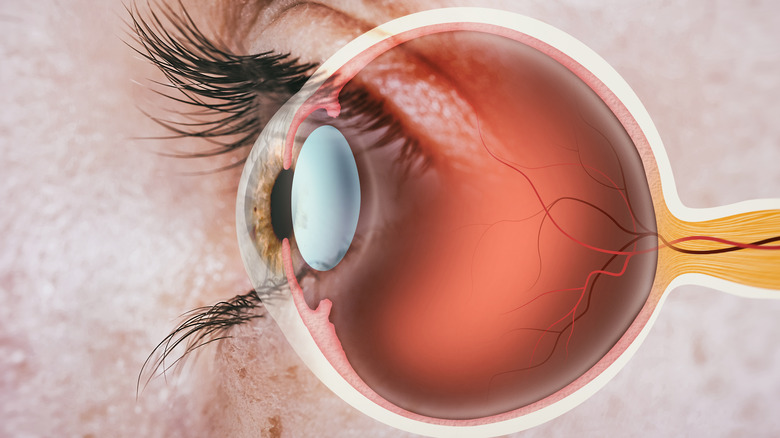

Corneal transplants, in which the clear, front layer of the eye is restored through a living donor, are common procedures, according to the American Academy of Ophthalmology. And in 2021, doctors in Israel successfully implanted the first synthetic corneal implant into a 78-year-old sightless patient, according to Insider. However, this differs from an entire eye transplant, which is more complicated because of the eye's connections to the brain.

The challenge

The eyes are connected to the brain through the optic nerve. Through this nerve, information we see through the eyes is sent to the brain, where it is interpreted as the living images we see, per the American Academy of Ophthalmology (AAO). Within this nerve are upwards of 1 million nerve fibers — like the fiber optic cable of your internet connection — and connecting these million-plus nerve fibers is what makes full eye transplants impossible. Doctors would have no problem transplanting the physical eye in its socket, but it wouldn't allow patients to see unless it was properly connected to the brain, and severing these nerve fibers in surgery is irreversible (per the AAO).

However, two decades ago, scientists said that many models of transplantation were also impossible, but with advancements in technology they have become everyday procedures, according to STAT News. With a combination of stem cell research and genomic research, scientists at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center think that they will be able to accomplish the first human eye transplant within the next decade.

The blind mice

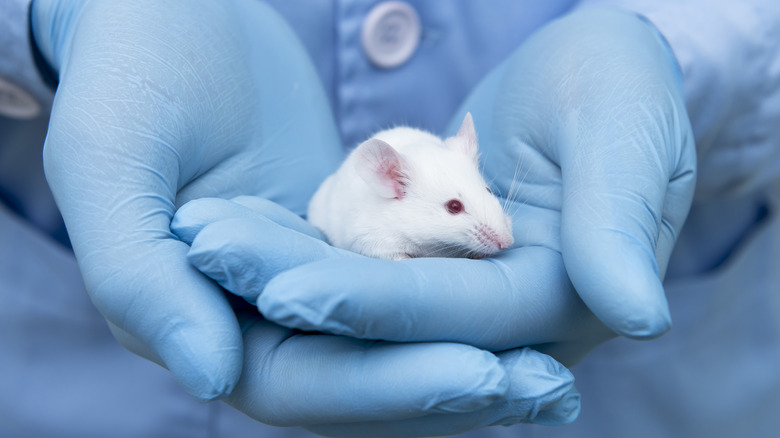

The journey to understand how to perform an eye transplant began in three stages, with a group of blind mice. First, the research group noticed in experiments with mice that rodents with a missing gene called BAX maintained the optic nerve even after they were injured, according to STAT News. If they could replicate this protection of the optic nerve in humans, through certain drugs that temporarily block this gene, for example, it could help preserve the finicky nerve during surgery.

But while that would help preserve the nerve, scientists would still have to attach the new transplant successfully. Because suturing each of the million fibers on a microscopic scale is not presently possible, researchers looked for a way that the nerve could grow back toward the brain itself, as it does in development. Once again, the researchers were able to accomplish this regrowth with a group of drugs administered to the mice, and their nerves grew back within a month, says STAT News.

However, after these two drugs were administered, the mice remained blind. What was missing, the researchers discovered, was that the new nerves were too young and hadn't yet developed the insulation that adult nerves have to hold the electrical signal in the nerve, so it can successfully reach the brain. Administering yet another type of drug to the mice restored this insulation. At last, the blind mice could see.