The Brutal Truth Of The 1941 Disney Animators Strike

Nowadays, organized labor groups are fairly common in the entertainment industry. Writers often belong to the Writers Guild of America, camera operators can join the International Cinematographers Guild, and actors often hope to someday earn themselves a SAG-AFTRA card.

This was a process that didn't happen overnight, and in the early 1940s, the organized labor movement in Hollywood reached animation. Animators' unions were present at both Universal Studios and Fleischer Studios, the studio behind cartoons featuring the likes of Betty Boop and Popeye the Sailor. According to Gizmodo, the Screen Cartoonists Guild attempted to set up a similar union at Walt Disney Studios. This attempt came at the end of several years of evolving unionization attempts within the studio, a process that actually started as a means of blocking a union helmed by a known mobster from infiltrating the studio, per HistoryNet. A series of events led to the studio firing employees who attempted to join the Guild, which in turn led to a full-on strike. Disney's animators were joined by their animation compatriots from around town.

Walt Disney's complicated political views

Much has been said about Walt Disney's political views. As he grew older, Walt is thought to have become considerably more conservative, even while at the same time, Hollywood was growing increasingly liberal, per ThoughtCo. Walt was known to be staunchly anti-communist, according to The Guardian, but it doesn't appear that his point of view was a product of McCarthyism or the red scare of the 1940s and '50s. (Disney did however testify before the House UnAmerican Activities Committee.) The seed for his disdain for such left-wing ideologies came decades earlier.

When Walt and his older brother, Roy, were growing up, their father was a proud socialist. Elias Disney had tried and failed at several business ventures, something it appears Walt later blamed partially on his politics. According to Collider, Walt noted that while Elias was an honest man, he naively thought everyone else was, too. "He got taken in many times because of that," Walt said. Ironically, according to PJ Media, Walt taught himself to draw — the very skill that made him millions — by copying cartoons from his father's issues of the socialist newspaper titled Appeal To Reason.

The Disney brothers went in the other direction and, while Walt voted to re-elect Democratic President Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1936, he and his brother remained fairly consistently conservative in their beliefs despite Walt's attempt to promote an apolitical public image. Writer Maurice Rapf, who worked on several of Disney's films, noted that Walt "was very conservative except in one particular — he was a very strong environmentalist."

Organized labor comes to Walt Disney Studios

In 1937, the International Association of Stage and Theatrical Employees, or IATSE, was growing and becoming increasingly powerful in Hollywood. However, there was a problem: The organization's west coast leader was Willie Bioff. Bioff was a known mobster with ties to Al Capone, according to HistoryNet. Under his leadership it became something of an open secret in town that IATSE would take entire studio departments under its wing, only to immediately threaten a strike if Bioff wasn't paid off. It was essentially a racketeering operation, per Variety, and Art Babbitt, one of Disney's highest-paid animators, didn't want it anywhere near Walt Disney Studios.

The same year, just before "Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs," the first animated feature-length film premiered, Babbitt read about Bioff in Time magazine. Babbitt, who according to PJ Media held left-wing political views, approached Roy Disney over his concern that their studio would be the next one on Bioff's list. Roy sent him to the studio's lawyer, Gunther Lessing, and together Babbitt and Lessing drafted what was described as a "social organization" called the Federation of Screen Cartoonists. While this would effectively accomplish Babbitt's goal of keeping Bioff at bay, what he didn't realize was that Lessing had pulled something of a quick one and had created an in-house union that was controlled by the studio.

Babbitt joins the Screen Cartoonists Guild and tough times at Walt Disney Studios

Disney's Federation of Screen Cartoonists was approved by the National Labor Relations Board on July 22, 1938, at which point it was named the only union for Walt Disney Studios employees. However, when the Federation tried to ink a deal with Roy Disney they came up empty, which meant that their union didn't wield any kind of power, and the Federation was disbanded, per HistoryNet. Some animators at Disney started joining another, independent union known as the Screen Cartoonists Guild. When Walt caught wind of this in 1940, he called several of those animators — including Babbitt — and told them to revive the Federation.

"I would have liked to have said to Walt, 'Well, you're the boss — whatever you say goes,'" Babbitt said when the Federation reconvened, but he felt obligated to make things right to the other employees who had followed him into the now powerless union. He quit the Federation and continued going to Guild meetings.

Meanwhile, Walt Disney Studios had run into a financial bind when the onset of World War II prevented films like "Pinocchio" and "Fantasia" from becoming financial successes, partially because the European market had virtually disappeared, according to Collider. The studio went into substantial debt, and employees started fearing for their job security. This made the idea of unionizing very attractive once again, which caused great concern for Walt Disney, who was afraid that the higher salaries the studio would need to pay unionized employees would put them out of business.

The animators go on strike ... and get theatrical

Tensions were rising between those who wanted to unionize and the studio. Babbit had become the chairman of the Screen Cartoonist Guild's Disney unit, according to Collider, and this continued to cause friction with Walt. He reportedly approached Babbitt in a studio hallway and told him he'd be fired if he didn't stop, per HistoryNet. In May 1941, 24 employees — all of whom were Guild members — were laid off. Guild representatives asked to meet with Disney to discuss the situation, but he refused. Then, about two weeks after the layoffs, Babbitt was fired, which led to the Guild members voting to strike.

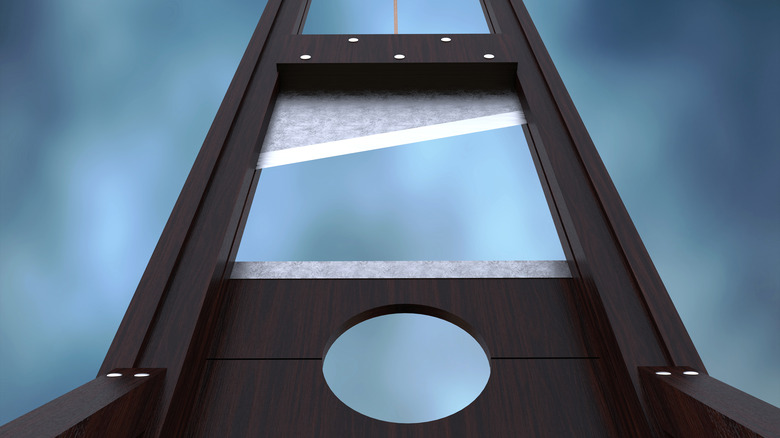

As many as 300 Disney animators marched all day and all night brandishing signs that featured an array of Disney characters. Soon they were joined by their colleagues from other studios. Animators from Warner Bros. built floats and props for the occasion, including one that mirrored the kind of anarchic spirit seen in their characters. They lugged a full-sized guillotine to the picket line, and strapped to it was a dummy dressed up to like a certain lawyer on Disney's payroll: Gunther Lessing. According to Gizmodo, this procession was headed by none other than legendary animator Chuck Jones, the creator of several of Looney Tunes' cast of characters. Jones sported a black, executioner-style mask and waved a sign that read, "Happy Birthday to Gunther and Walt" before he and his fellow animators released the guillotine's faux-blade, and it fell on the Gunther Lessing dummy's neck.

Walt's reaction to the strike

According to Collider, lots of employees were aware that Lessing was in some ways pulling the strings. He was extremely anti-union and is thought to have prodded the Disneys' anti-communist inclinations to keep them at odds with the Guild. Ward Kimball, a legendary animator and one of Disney's famed Nine Old Men, would later say, "Walt was a nice guy. He was wrapped up in his cartoons and animation, so he relied on what Gunther Lessing told him [about the union], and Gunther Lessing was a pack of lies." Even if some of his employees didn't point the finger at him, Walt was still incensed by what was happening at his studio, though it appears his ire was misguided.

Babbitt and an artist named Dave Hilberman, who helped organize the strike, were said to have communist leanings, but the vast majority of the other employees did not, per PJ Media. Still, Walt and Roy decided to blame the attempts at unionization and the strike on communism.

Roy Disney would later say that he and his brother felt that "money was never the basic problem in this thing, as much as communism." Roy was renowned for being the financial brains of the Disney operation, so whether he truly thought that communism was to blame or not, he would have no doubt been aware of the studio's difficult financial situation at the time and how it would have factored into the series of events that led to the strike.

The strike comes to an end, and Babbitt's career continues

Babbitt claimed that the Guild represented the majority of the studio's animators, which Walt doubted. Eventually, the Guild asked if they could compare their enrollment list to Disney's payroll, but he declined, saying instead of saying that he wanted to leave it to an employee vote as to which union the company's animators would become part of. Walt's refusal to have the Guild crosscheck nearly put the studio in deeper financial trouble, as this inched the studio closer to landing on a list of companies and studios that union animators should stay away from.

Eventually, both sides agreed to bring mediators from the National Labor Relations Board. They arrived in late July, and less than one week later, ruled in favor of the Guild. The studio was required to ink a deal with the Guild, and its members saw 25% pay increases and 100 hours in back pay, according to HistoryNet. The animators went back to work, but for whatever reason, there was suddenly no work for Art Babbitt to do, which led to him being laid off that November. He — with the help of the Guild — sued the studio in October 1942 and came out victorious.

Art Babbitt won his job back, but with the United States at war, he enlisted in the Marines and served for three years in the Pacific. Disney kept his position open, but the relationship was irreparable, and he left the company in 1947. Babbitt worked at other studios, including United Productions of America and Hanna-Barbera. Per Walt Disney Archives, Babbitt retired in 1983; he died in 1992.