Thomas Jefferson And John Adams Vandalized A Chair That Belonged To A Famous Playwright

By the year 1800, Thomas Jefferson and John Adams were bitterly waging war against each other in the press. Jefferson accused Adams of being an effeminate reactionary with a secret lust for the monarchy. Adams accused Jefferson of being a lover of the guillotine who performed secret rituals on his Monticello plantation. Adams called Jefferson cruel, and Jefferson called Adams fat (via Constitution Daily/Miller Center/Mental Floss). If this feud sounds personal, that's because it was.

Once upon a time two decades prior, Adams and Jefferson had an intimate friendship. After forging a bond at the Continental Congress, the two exchange countless letters, many of which describe their mutual affection (via Monticello): "[My] intimate correspondence with you... is one of the most agreeable Events in my life," Adams wrote to Jefferson. Per John Adams' Diary on Founders Online, while on separate diplomatic missions in 1786, the two best friends met up for a thrilling foray across Great Britain's cultural sites that would involve vandalism, petty theft, lecturing British strangers for disrespecting "liberty," and "mount[ing] Ld. Cobhams [sic] Pillar, 120 feet high, with pleasure."

'According to Custom'

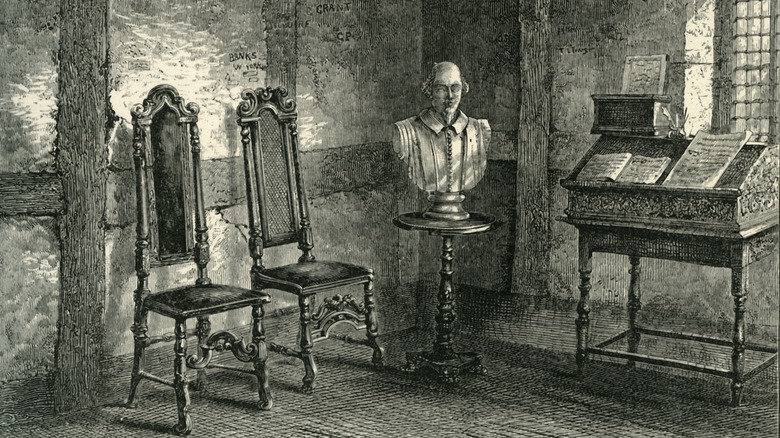

The two future presidents took a break from their diplomacy to enjoy a visit to the home of William Shakespeare. (Their love for the playwright was no secret, according to White House History.) John Adams and Thomas Jefferson arrived in Stratford-Upon-Avon in April 1786. Adams was not impressed. In his diary (via Founders Online), he described the house where Shakespeare had been born, now a tourist destination, as "as small and mean as you can conceive." When they were shown "Shakespeare's Chair, "[w]e cutt off a Chip according to the Custom," Adams wrote in his diary.

"According to the custom?" Vandalism and defacement were relatively common in the late 18th century, and they were indeed near-obligatory at the home of William Shakespeare. "If you could not take away a piece of the bust, presumably the alternative was to leave your mark — both were forms of appropriation," wrote Nicola J. Watson, author of "Shakespeare on the Tourist Trail" (via "The Cambridge Companion to Shakespeare and Popular Culture"). "The sanctioned practice of graffiti [was] indulged in by some of the earliest visitors [to Shakespeare's home], including Sir Walter Scott."

Shakespeare's Chair

Mrs. Hart, the proprietor of "Shakespeare's Chair" at the time of John Adams' and Thomas Jefferson's visit, was less-than-thrilled with this practice. She bemoaned the many bardolaters (overly zealous Shakespeare enthusiasts) who flocked to Stratford-Upon-Avon to vandalize, deface, and outright plunder raw materials from the bard's birthplace. "[A]nd now see what pieces they have cut from it, as well as from the old flooring in the bedroom!” she lamented to John Byng (via "Shakespeare on the Tourist Trail").

Did Mrs. Hart feel the same irritation toward John Adams and Thomas Jefferson? Upper-crust bardolaters themselves, the United States' second and third presidents were not at all above the exact petty vandalism Mrs. Hart described. Its evidence exists to this day. Curators of Jefferson's estate discovered a splintered shard of wood accompanied by a note with his handwriting (via Monticello): "[a] chip cut from an armed chair in the chimney corner in Shakespear's [sic] house at Stratford on Avon,... Cut by myself in 1785."

In the end, Jefferson and Adams twice faced off for the presidency, Adams arrested the journalists who insulted him, Jefferson returned to his over 600 enslaved people, and the two later made up. The demigods were not demigods, but very much men. (And vandals. They were also vandals.)