The Messed Up History Of Diabetes

Diabetes has been around for thousands of years, and due to the distinctive sweet taste of a diabetic's urine, the disease has been accurately diagnosed for a long time. On the other hand, no one really knew what it was or how to cure it.

Many doctors incorrectly believed it to be a kidney disease, and plenty of early treatments were dangerous in and of themselves. Physicians are a tenacious bunch, however, and began to crack the secrets of diabetes, even if it was in ways they didn't expect. Since so many doctors were working on the same issue, research had a tendency to overlap. Treatments for diabetes tended to focus on diet, and since a popular treatment in the 19th century was getting the body as close to starvation as possible, many people with diabetes died from it (via Diabetic Gourmet). Unfortunately, many died young before the stable treatment of insulin came along, simply due to the toll of the disease and its complications on the body.

On the bright side, once insulin was discovered, things got better. Not perfect, since type 2 diabetes has been rising in children over the past two decades, but better. Let's dig into some awful aspects of diabetes.

For centuries, people tasted urine to diagnose diabetes

Before glucose tests were invented, people spent centuries tasting urine to diagnose diabetes. Due to its consistently sweet flavor, it was easy to recognize. According to Sekisui Diagnostics, people called "water tasters" had the job of actually drinking urine to test for disease.

Diabetes was first diagnosed by frequent urination around 1550 B.C., according to Everyday Health. Physicians also noticed that insects were interested in the urine of patients; eventually, they discovered it was because of the sweet flavor, and so the role of a water taster was invented. In the Middle Ages, physicians created an entire practice around using urine as a diagnostic tool called uroscopy, writes Sekisui Diagnostics. Diabetes was the only disease they consistently diagnosed correctly.

In 1675, the word "mellitus," or "honey," was added to "diabetes" (which means "siphon") to indicate the sweetness of urine in people with diabetes (via Everyday Health). Thus, the scientific term is "diabetes mellitus."

Early modern treatments failed

Even in the early modern era, treatments failed. So-called diabetes cures that were peddled in the 19th and 20th centuries contained arsenic, opiates, and bromides, and didn't work to boot (per Because of Her Story). A few decades later, peddlers began including pancreatic extracts in their formulas since researchers had figured out that the pancreas was involved in diabetes, even if it wasn't entirely understood how yet.

Matthew Dobson, a 17th-century physician, did make some strides in his research, though he also failed in his treatments. By 1776, he had treated nine patients for diabetes and conducted a number of experiments, writes Ian Macfarlane in "Matthew Dobson (1735-1784) and diabetes." One such experiment involved evaporating a patient's urine, after which Dobson found that the remainder was a white powder that tasted like brown sugar. Ultimately, he had discovered hyperglycemia, or high blood sugar, according to the Science History Institute.

On the other hand, Dobson also proposed several bogus treatments, limited by what physicians knew about medicine at the time. While treating Peter Dickonson for severe diabetes, Dobson used rhubarb and opium, neither of which worked. Dobson also suggested that the diabetic would be cured if he took in the waters at Matlock. Dickonson gave up the treatments after a few months, and his future is unknown.

Animals had to die for medical research to progress

Many researchers working in the 19th and 20th centuries first tested their theories on animals, dogs, and rabbits especially. Animal testing wasn't kind, and many died, especially since the researchers didn't really know how their test subjects would fare once exposed to experimental treatment.

Researchers Frederick Banting and Charles Best, who discovered insulin, began their research testing on dogs that they induced to be diabetic. At one point, writes Connected in Motion, they were buying them off the streets of Toronto because so many were dying. One particular dog, whom they had become fond of, inspired them to get creative with their extracts. Sadly, the dog didn't end up surviving the treatments.

According to Medical News Today, once Banting and Best began researching how to produce insulin on a large scale, they started to use cows over dogs and used their insulin to treat diabetes. Cow and pig insulin, after being further refined, was used for decades in treating diabetes.

Some research wasn't recognized

As diabetes was studied, hundreds of researchers were working separately on the same issue. Plenty of research either wasn't recognized for decades, like Thomas Cawley's autopsy of a diabetic, or didn't go far enough to reach a breakthrough, as was the case with Johann Conrad Brunner's pancreas experiments with dogs.

According to Hektoen International, Brunner, working in the late 1600s, was a family physician who was very interested in the pancreas. He succeeded in removing parts of the pancreas and did manage to induce diabetes in his animal test subjects but never made a connection between diabetes and the pancreas. That next step in diabetes research wouldn't be made for another 200 years by Oskar Minkowski and Joseph von Mering. Cawley, meanwhile, working around a century later, conducted an autopsy on a diabetic. Per "A Singular Case of Diabetes, Consisting Entirely in the Quality of the Urine; with an Inquiry into the Different Theories of That Disease," he found a possible relationship between diabetes and the pancreas after discovering signs of damage and kidney stones in the area. Researchers wouldn't follow up on this line of thought for decades.

According to "Unveiling Diabetes," many researchers were working on solving the same problems at the same time, showcasing that the history of diabetes research was progressing, with both failure and success along the way.

Recommended diets in modern times were contradictory at first

From the 17th century to the 20th, diabetic patients were advised to overeat, as that was thought to restore the nutrients that were being lost. However, several died from this so-called diet, and doctors instead began to suggest eating restricted diets. By this point, doctors didn't know what to suggest that would actually help people with diabetes live healthier lives and were doing their best with the limited resources available. Notably, physician Apollinaire Bouchardat discovered that restricted diets helped his diabetic patients through factors completely beyond his control: war rationing during the Franco-Prussian war in the 1870s (via Everyday Health). After this, he began personalizing diets for his patients.

According to Diabetic Gourmet, high-fat diets were also recommended, as were diets high in sugar. In the 1700s, Dr. John Rollo recommended a diet of meat and other animal protein such as blood puddings. George Henderson's "Court of Last Appeal — The Early History of the High-fat Diet for Diabetes" notes that several Michigan-based doctors in the 1920s felt that high-fat diets prolonged the lives of people with diabetes who were not being treated with insulin; however, two doctors (Elliott Joslin and Louis Newburgh) had differing opinions about the diet's safety. By the 19th century, doctors were mainly recommending low-calorie diets.

Everything changed when insulin was introduced in the 1920s. Diet was — and still is — a powerful force to monitor diabetes, but it was suddenly somewhat less important thanks to the arrival of insulin.

The starvation diet kept people with diabetes barely surviving

Working in the early 1900s, physician Frederick Allen took the restricted diet even further and advocated that people with diabetes (now known mainly as type 1 diabetes) to eat around 1000 calories a day, just barely enough to survive. This meant that they did live, though just barely, while glucose levels were kept low. Unfortunately, some patients did accidentally starve themselves to death.

In "Why were "starvation diets" promoted for diabetes in the pre-insulin period?", Allan Mazur notes some misconceptions regarding common beliefs about the starvation diet, namely that it was a last-ditch desperate effort by Allen and his colleague Elliott Joslin to apply animal experimentation to humans. This wasn't true, but it's possible that low-carbohydrate diets actually worked better than the starvation diet.

Regardless, Allen had no lack of patients in the years before the discovery of insulin. On the other hand, Mazur writes that nearly half of the 44 patients Allen had in 1915 were dead by the end of 1917, just two years later. Insulin would be able to bring these patients back from the brink just a few years after this, but Allen and Joslin advocated this type of barbaric treatment because it was simply the best they could do at the time.

Before insulin, life expectancy for people with diabetes was alarmingly short

Before the invention and distribution of insulin, life expectancy for people with diabetes was less than 10 years, though it was even more alarmingly short for children. People diagnosed with type 1 diabetes had few options and often died in ketoacidosis. Other than putting patients on strict diets, there wasn't much that could be done (per the American Diabetes Association).

Brostoff, Keen, and Brostoff's "A diabetic life before and after the insulin era" analyzes the life of the authors' grandfather, who was diagnosed with diabetes in 1909. Despite the life expectancy at the time being less than four years, he changed his diet and survived for 14 years before the discovery of insulin. He was on a succession of different diets, many of which brought him to the brink of collapse, but he survived. Insulin helped him live a long life, and he died at age 88.

After the invention of insulin, the Joslin Diabetes Center began to award people with diabetes who had survived over 50 years with the disease. Those who lived long lives while being treated with insulin were found to have specific characteristics in common, such as not needing a vast amount of insulin during injections.

Early insulin research was inconsistent

In the early 1900s, Georg Ludwig Zuelzer experimented with diabetic extracts; he had some success, but nothing universal. Despite the inconsistency of his treatment and several side effects, he took out a patent on his work, as Stylianou and Kelnar wrote in "The introduction of successful treatment of diabetes mellitus with insulin."

Several other scientists had some success in the following years but ceased work either due to lack of funding or discouraging results. According to Stylianou and Kelnar, Scottish physicians Thomas Fraser and John Rennie treated several patients with "principal islets" but found no discernible benefit. Around the same time, Belgium doctor Jean De Meyer attempted to extract a secretion from the pancreas but failed in the attempt.

Several other doctors abandoned their research in the process. Ernest Scott, working in Chicago, made some progress with aqueous extracts, noting that they lowered blood sugar, but only for a short time (he left the laboratory soon after). In Romania, Nicola Paulesco was busy solving sterilization problems that had already been solved in the U.S. and Canada. Overall, so many researchers were working on insulin that their work was bound to fail at different points in the process.

Many just missed the benefits of insulin

Plenty of people died just as insulin was getting off the ground. In the years just prior to 1923, when insulin began to be used for treatment, researchers were inching closer to the right answer, but they weren't quite there yet. Diabetes can also lead to complications, and those secondary illnesses were usually the true cause of death in many people historically. Thus, many people just missed the benefits of insulin.

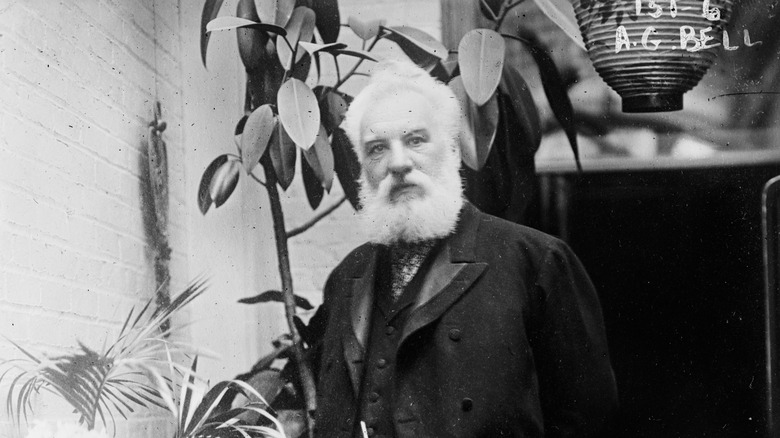

The inventor of the telephone, Alexander Graham Bell, died in 1922 of complications of diabetes, writes History. Though Bell spent much of his life advocating for the deaf through his inventions, he never entered the medical field. Argentine paleontologist Florentino Ameghino also died of complications of diabetes by way of gangrene. He was a well-known geologist and evolutionist who discovered over 6,000 fossil species (via Mayo Clinic Proceedings). He developed diabetes in 1890, which grew particularly bad after 1898, and died of gangrene in his foot in Argentina in 1911.

Complications from diabetes made everything worse

Since diabetes was untreatable for so long, people with diabetes were historically forced to fight off whatever complications arose in addition to the disease. Some treatments were actually prescribed for complications over diabetes, such as opium for gangrene, according to Ritu Lakhtakia's "The History of Diabetes Mellitus"; doctors were limited by what they knew.

Measuring blood sugar over the course of three months with the HbA1c test, introduced in the 1980s, became incredibly important in order to mitigate the risk of complications emerging in the eyes, nerves, or kidneys (via Lakhtakia). A study conducted in the Diabetes journal researched the rates of various diabetes complications in patients who had been diagnosed at different times in the recent past, finding that kidney failure was declining in people with type 1 diabetes.

Though modern medicine is miraculous and will only continue to get better, there are so many people with diabetes across history who died of complications without knowing anything that could save them. Having one disease is bad, but having another that kills is infinitely worse.

The obesity epidemic contributed to the rise in type 2 diabetes in children

While insulin has been helpful for type 1 diabetes, cases of type 2 diabetes have raised in the past two decades, notably in children. The obesity epidemic is a major factor, as are poor eating habits and lack of exercise overall (via Healthline).

Obesity changes the body's ability to use the insulin it produces, which in turn causes erratic blood sugar levels, per "Addressing Childhood Obesity for Type 2 Diabetes Prevention: Challenges and Opportunities." From 2000 to 2015, childhood obesity doubled. In addition to type 2 diabetes, obese children are also at higher risk for lifelong diseases and conditions such as high blood pressure. It is also highly likely that they will be obese as adults, which might also lead to diabetes and heart disease.

David Haslam considered how diabetes and obesity were intrinsically linked through the history of the disease in his article "Diabesity — a historical perspective: Part II," noting that obesity rose throughout the 20th century along with diabetes. The term diabesity was coined in 1939, and sadly, this trend has only continued to rise rather than fall.

Drugmakers pushed glucose-lowering drugs, leading to an epidemic of hypoglycemia and death

For the past two decades, a major drug campaign has pushed people with diabetes to lower their A1c scores (measuring blood sugar) to below 7 percent, writes Reuters. Doctors have also promoted reaching this number as a good plan of treatment. However, this intense lowering leads to hypoglycemia, which induces confusion and a loss of coordination.

Many patients have either been hospitalized or died due to the treatment's hypoglycemia effect. According to The New York Times, a 2008 federal diabetes study altered its course after 54 more people died in the group with highly moderated blood sugar levels than in the group with less moderated levels. All the participants were then immediately put on the less strict schedule for monitoring their blood sugar levels in hopes of avoiding further deaths.

More recently, many more people with diabetes have died of COVID-19 due to this inadequate management of their disease and vulnerability to the virus, though they didn't know that at the time. Over the past several years, hypoglycemia crises have increased, especially for people with diabetes who are 65 and older. Even then, doctors say that there are likely more hypoglycemia deaths than they know about.