Washington Post's First City Editor Defended A Lincoln Assassination Conspirator

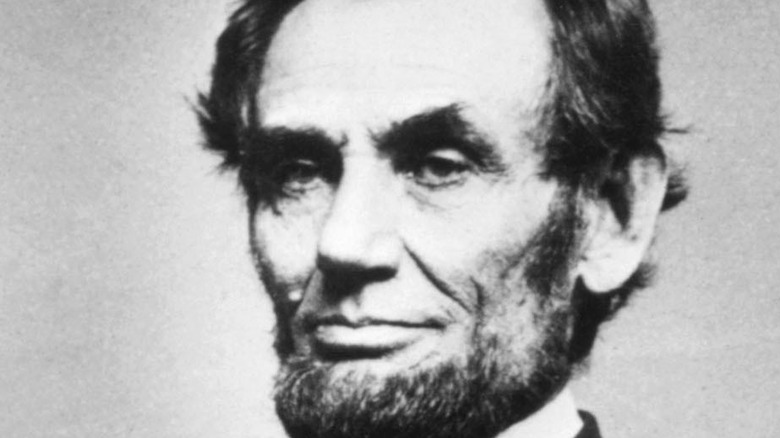

He was a war hero and a journalist, but Frederick Aiken is best known for defending one of America's most notorious criminals. In 1865, he was one of the lawyers for Lincoln assassination conspirator Mary Surratt.

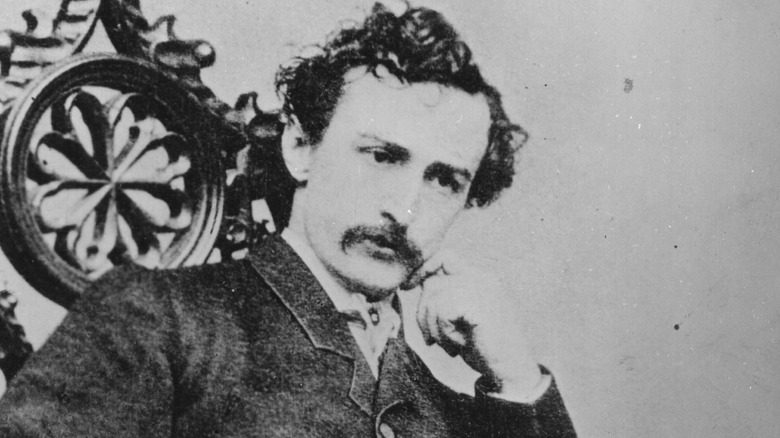

Aiken had mixed loyalties. Though he was northern — born in Massachusetts and grew up in Vermont — he was a Democrat with southern-leaning sympathies. He was already an established journalist at the start of the Civil War, having been associate editor of the Burlington Sentinel in Vermont. In 1860, he and his wife moved to Washington, D.C., where he wrote theater reviews and may have known John Wilkes Booth (via The Washington Post).

According to the The American Film Company, during the war, he wrote to Jefferson Davis, the president of the Confederacy, to offer his services as a writer. However, he was also a spy for the Union, infiltrating groups of Confederate supporters in New York City, according to The Washington Post. The letter to Davis could have been part of his espionage work. He also served as aide de camp to two different Union commanders and was wounded in the line of duty (via The American Film Company).

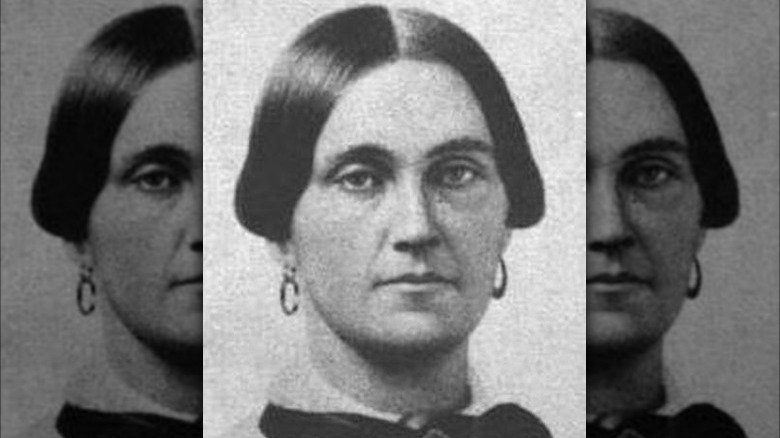

Who was Mary Surratt?

Mary Surratt was a 42-year-old mother of three at the time of the Lincoln assassination. She owned a tavern in Prince George County, Maryland, and a boarding house in Washington, D.C. Both became meeting places for those involved with the assassination conspiracy. The tavern may also have served as a safehouse for Confederates. After Surratt's husband died, she rented the tavern out to John Lloyd, who would later testify against her in her conspiracy trial. One of her boarding house tenants, Lewis Weichmann, who was her son's classmate, also testified against Surratt.

According to Weichmann, John Wilkes Booth visited Surratt's boarding house multiple times, and Surratt had private conversations with him and Lewis Powell, another assassination conspirator. Weichmann drove Surratt out to her tavern on April 14, 1865, the day of the assassination, and she delivered a package to someone there. Weichmann also saw Booth at the tavern, speaking to Surratt.

Lloyd testified that Surratt's son and others had hidden weapons and ammunition at the tavern weeks before the assassination and that Surratt had later told him it would be needed soon. On the night of the assassination, one of the conspirators confessed to Lloyd what they had done (via the University of Missouri Kansas City).

Aiken's defense of Surratt

Aiken, along with his law partner, John W. Clampitt, defended Surratt. They may have been chosen because of their connections within the Democratic Party, according to amateur historian Christine Christensen. Ironically, Aiken and Clampitt had previously been chosen to write the Democratic Association's response to the assassination, which promised to help solve the crime. Opponents of Aiken's claimed that the writer was personally acquainted with Booth and Surratt — possibly true — and that he had "always been a bitter pro-slavery democrat."

In his defense of Surratt, Aiken claimed that Lloyd was a drunk and his testimony shouldn't be taken seriously, and that he was trying to shift blame onto Surratt to save himself. Nevertheless, Surratt was found guilty, mainly on Lloyd's testimony. Several members of the Military Commission, which oversaw the trial, recommended commuting Surratt's sentence from death to life in prison because of her gender and age. President Andrew Johnson refused, saying Surratt "kept the nest that hatched the egg." On July 7, 1865, Surratt became the first woman executed by the U.S. government (via the University of Missouri Kansas City).

Aiken's other scandals

According to The American Film Company, Aiken and Clampitt's law firm dissolved not long after the trial, possibly because their defense of Surratt had damaged their reputations. Within a few years, Aiken became involved in two other scandals. Only a year later, in July, 1866, Aiken was arrested twice for "obtaining money under false pretenses," according to Christine Christensen. He had cashed a check which then bounced because he had insufficient funds in his bank. However, he was evidently not jailed for the offense, because he was involving himself in politics by September.

Two years later, in 1868, the National Republican newspaper reported extensively on what it called "the Contested Child case." Aiken and his wife were in a legal battle with a woman named Ellen McCall for custody of a child. Supposedly the child, Cora, was McCall's, but she had given her to the Aikens to raise. McCall was a prostitute and thus considered unfit to raise Cora. However, she claimed that Aiken had been her client and was thus also morally unfit (via Christine Christensen). The case ended with Cora being put in an orphanage (via The Washington Post).

Aiken's wife

Aiken's wife was a remarkable woman in her own right. Born Sarah Olivia Weston, she was the daughter of Judge Edmund Weston. She and Aiken married in 1857, according to Christine Christensen. After their marriage, Aiken apprenticed with her father to study law before being admitted to the Vermont bar in 1859 (via The American Film Company).

Sarah was highly educated for a woman at the time. Her father hired private tutors to teach her English, classics, languages, and music. She became one of the first women to attend what was then Harvard College, according to the American Film Company. A newspaper later claimed that she knew nine languages. Like her husband, she was a writer and published stories, poems, and reviews in the Burlington Sentinel and other publications, according to Christine Christensen.

She was caught up in the "Contested Child" case too, writing a letter to the court about why she and Aiken should be permitted to raise Cora. Though Sarah Aiken's reputation was noted to be flawless, they still didn't win the case. After Aiken's death, she supported herself as a newspaper correspondent and a clerk for the Treasury Department, according to Christine Christensen.

The rediscovery of Aiken's legacy

Aiken became the Washington Post's first city editor in 1877 but died only a year later. Other than his defense of Surratt, very little was known about Aiken until Christine Christensen began to take an interest in him around 2010. She became curious about him because her favorite actor, James McAvoy, played him in the movie "The Conspirator," which told the story of Mary Surratt. Christensen began to research Aiken, primarily at the Family History Library in Salt Lake City. By March, 2012, she had written a 29-page paper on his life. She uncovered information about his early life, his war service, his political participation, and his scandals (via Christine Christensen and The Washington Post).

One of Christensen's other discoveries was Aiken's gravesite. He had been buried in an unmarked grave in the Oak Hill Cemetery in Georgetown. In 2012, a group from the Surratt House Museum placed a marker at the site of Aiken's grave and dedicated it (via The Washington Post). The museum is located in the building that was Surratt's tavern. Etched on the grave is a quote from Aiken's defense of Surratt: "For the lawyer as well as the soldier, there is an equally pleasant duty — an equally imperative command. That duty is to shelter from injustice and wrong the innocent. To protect the weak from oppression" (via Find A Grave).