The Strange History Of The Martial Art Bartitsu

There's an iconic scene in the 2009 "Sherlock Holmes" movie where Holmes use his brilliant mind to strategically beat the candy out of his opponent in a bare knuckle boxing match. Holmes wasn't just a brainiac brawler, he was practicing the gentlemanly art of bartitsu –- self defense for the Edwardian gentleman.

The sport combined elements of boxing, kicks from savate, grappling and throws from jiu-jitsu, and cane fighting. It was one of the first modern mixed martial arts to be taught in England. Bartitisu burst onto the scene during the era's fitness craze when people sought to perfect their bodies and ushered in a new interest in Eastern martial arts.

It was unfortunately something of a fad, having fizzled out in just a few years of practice among the London elite. It nearly faded into the dustbins of history were it not for a few dedicated revivalists who have preserved the philosophy of its creator, Edward William Barton-Wright.

Who was the founder of bartitsu?

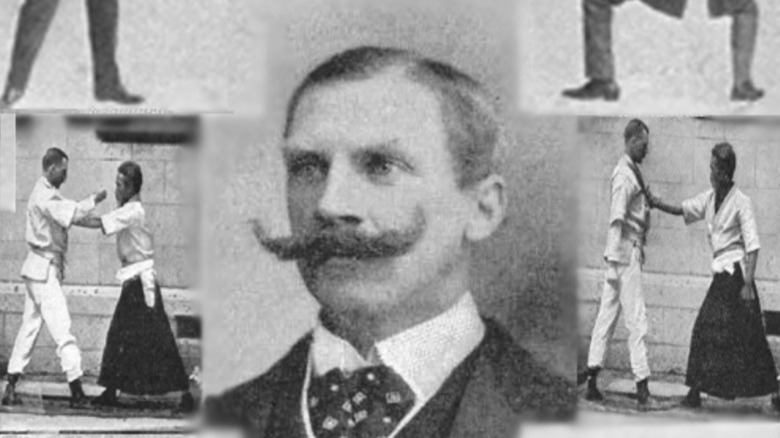

Edward William Barton-Wright was an Englishman born in Bangalore, India, in 1860. He was the son of a railway engineer and traveled frequently throughout his childhood (via The Bartitsu Society). As a young man he always had a fascination with studying martial arts.

According to Black Belt Magazine, while living and working in Japan in 1895, Barton-Wright began training at two dojos. He learned Shinden-Fudo Ryu jiu-jitsu under the tutelage of sensei Terajima Kuniichiro in Kobe and Kodokan jiu-jitsu with Kano Jigoro in Tokyo.

Barton-Wright is credited with promoting Eastern martial arts styles to the West, particularly in London. When he returned to London after studying Japanese jiu-jitsu, he began developing bartitsu from jiu-jitsu, French kickboxing, and la canne. He promoted the art through manuals showcasing his new self defense style with photos demonstrating the moves in Pearson's Magazine. Later, people flocked to exhibitions where his instructors would perform stunts and test their wrestling and boxing skills against jiu-jitsu.

He was an entrepreneur with a strong passion for learning and teaching self defense, as well as practicing physical therapy. When his Bartitsu Club shuttered its doors in 1903, Barton-Wright refocused his energy into being a physical therapist. As Black Belt reports, he specialized in using heat, light, and electrotherapy in his practice. He passed away in 1951 at the age of 90.

The need for self defense on the gritty streets of London

When bartitsu was being promoted, crime in British cities was still quite rampant. According to Britannica, London's Whitechapel murders and the deeds of Jack the Ripper were still fresh in the public's mind, having taken place between 1888 and 1892. But the majority of street crimes were not always violent. They were often committed by young men and consisted of petty thefts, as per the BBC.

Edward William Barton-Wright designed bartitsu in this climate where people feared the growing dangers of small street gangs and other opportunistic criminals. Newspapers at the time were filled with sensational stories of violence (via The Bartitsu Society). Bartitsu was meant to appeal to middle- and upper-class men as self-defense for the gentleman.

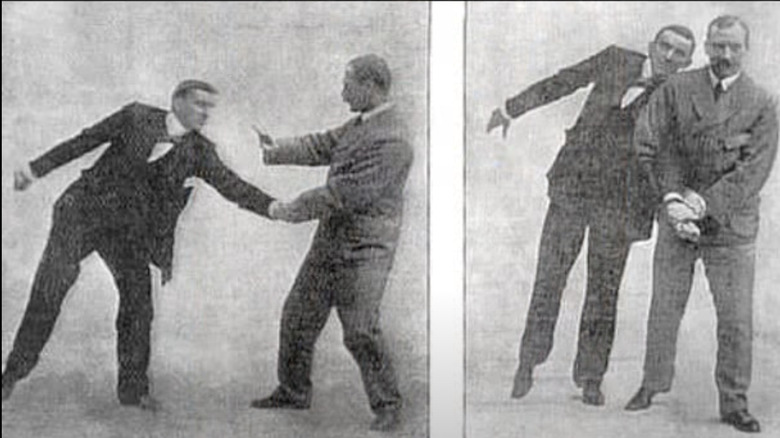

In Barton-Wright's first essay in Pearson's Magazine, titled "How a Man May Defend Himself Against Every Form of Attack," he explained street fights often result in your opponent using dirty tactics to win. The opponent in a fight may also resort to using weapons such as chairs, knives, or bottles. He claimed that British gentlemen are conditioned to fight using respectable tactics (not beating a man while he is down).

This was a disadvantage in his eyes, so he developed bartitsu as a means to suppress the attacker, not necessarily kill them. Barton-Wright wrote, "... it is not necessary to break the man's arm to show his power, though he could do so if he wished ..." The goal was simply to fend off criminals.

Bringing jiu-jitsu to Great Britain

As the Bartitsu Society details, E.W. Barton-Wright was under the tutelage of sensei Terajima Kuniichiro from 1895-1898. It was at the sensei's dojo that Barton-Wright discovered and learned the art of jiu-jitsu, which subsequently sparked his passion of bring mixed martial arts to the masses. He always had an interest in self defense, but his main motivation was to spend his time exercising rather than sitting idle after work. When he returned to London he began publishing his manual on the new art of bartitsu.

Thankfully for Barton-Wright Londoners were itching to learn more. With a sharp rise in more sedentary middle class jobs, people of the era were suddenly obsessed with new forms of exercise. According to the Conversation, British people were afraid their bodies had become weak with the advent of all the technological advances available.

Barton-Wright also benefited from the growing interest in Japan, as the Bartitsu Society reports. Up until the 1850s, Japan had been deliberately practicing isolation and made limited contact with the rest of the world. The United States Navy forced Japan to open to foreign trade with the West in 1854 and fostered new access to Japanese culture. Barton-Wright was the first Westerner to bring Japanese martial arts to Europe — he opened the Bartitsu Academy of Arms and Physical Culture (known as the Bartitsu Club), in London upon his return.

He invited several masters in la canne, savate, jiu-jitsu, and boxing to teach their methods. He brought over two men from Japan to be jiu-jitsu instructors, Yukio Tani and Sadakazu Uyenishi. Pierre Vigny, a French master at arms, was employed to teach la canne, a martial art that uses a walking stick, and savate (French kickboxing).

La Canne, Pierre Vigny's Contribution

The walking stick was a very common fashionable item that men often carried about town and signified distinction and authority. Black Belt Magazine reports, in the 1800s, la canne was born in France, utilizing the popular accessory for self defense. Pierre Vigny took la canne to new heights.

Vigny spent his youth learning different martial arts, including fencing, boxing and savate. He served in the military, and when he retired he opened his own combat academy. This is where he perfected his technique with la canne.

According to Martial Art Studies, Vigny came to work for Barton-Wright in 1900. He was employed as the chief instructor of bartitsu. Vigny and Barton-Wright worked together to adapt the art of cane fighting to include jiu-jitsu. They experimented with methods of defense and offense against different types of fighting styles (for example if your opponent was unarmed or if they were a skilled boxer or proficient at kicking attacks).

Martial Arts Studies reports that practitioners swung the cane by manipulating the wrist and using the hips to strike attackers. The bartitsuka (the name of a bartitsu practitioner) would attempt to keep an opponent at a distance with the cane. Other moves included using the cane to injure an attacker's joints or disarm them should they also be carrying a stick (via "Self Defense with a Walking Stick," by E.W. Barton-Wright).

Savate, aka French kickboxing

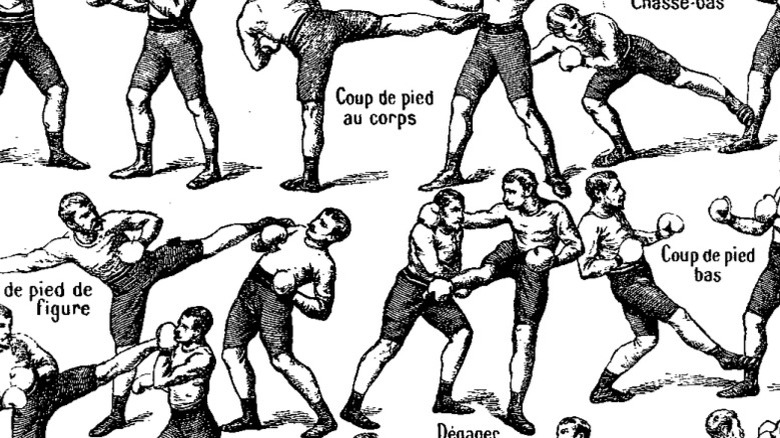

Pierre Vigny also instructed students in a form of French kickboxing called savate. Savate, meaning "old shoe," was derived from a form of street fighting that was found in larger cities like Paris (via Britannica). The style uses kicks that use the foot to make strikes and open handed punches.

Using kicks in bartitsu did not have the same importance as cane fighting or jiu-jitsu, The Bartitsu Society reports. E.W. Barton-Wright recognized that they were useful for countering assailants. Additionally, he rebranded his adaptations of savate as more effective than the original French practitioners. The Bartitsu Society reveals there was intense nationalism and bias against kicking. Along with savate-style kicks, Barton-Wright incorporated a limited number of its guards and parries to act as transitions between using the walking stick or cane.

It seems more than anything the students at the Bartitsu Club learned to use savate to learn to defend against it with their canes. These likely included "coup de pied bas," a sweeping kick to the legs, or a lateral kick aimed at the torso, head, or thighs (via Art of Manliness). The Bartitsu Society reports Vigny may have taught these basic offensive savate moves in sparring role play scenarios.

Pugilism and British boxing was also included

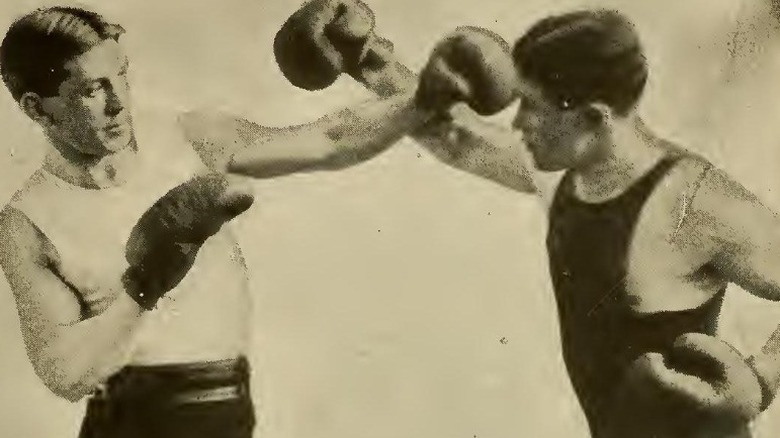

Boxing was a popular sport throughout the Victorian and Edwardian periods in England. Abandon notions of quick feet dancing in the ring and fighters expertly ducking and dodging blows from their opponent. Towards the dawn of the 20th century, boxers fought in rigid upright stances with a low guard (via Art of Manliness).

However boxing was a brutal blood sport until the establishment of London Prize rules in 1838, as Britannica reports. Fighters didn't wear gloves, and prior to the rules, they could wrestle, gouge, and brawl. In 1867 the sport became more civilized and began the three-minute round structure known today. The rules did little to improve the engagement of middle classes, since the sport was associated with all sorts of social ills (via Britannica).

E.W. Barton-Wright had his objections to the effectiveness of boxing for self defense. In an interview in 1901 with the Pall Mall Gazette (via the Bartitsu Society), he outlined his main criticism that boxing was too predictable and by-the-book. He argued boxing schools did not teach how to use force and was only useful when assuming the other fighter will fight following the rules.

Due to its popularity (especially with bare knuckle boxing being more accessible for lower classes), Barton-Wright incorporated some of the techniques. Unfortunately, according to the Bartitsu Society, Barton-Wright was not specific as to how he and his team employed boxing guards. He only told the Pall Mall Gazette that they "will make the assailant hurt his own hand and arm very seriously."

The Bartitsu Club in London

The Bartitsu Club was short-lived, but it occupied a special place in London. The Bartitsu Academy of Arms and Physical Culture opened in 1899 in the Soho district at 67b Shaftesbury Avenue (via the Bartitsu Society). Here E.W. Barton-Wright invited his international team of martial artists to train men –- and women -– from the upper classes in his new form of self defense (classes were separated by gender).

Unlike in modern times, where a prospective gym member simply signs up and pays for lessons, at the Bartitsu Club, you had to be voted in by a committee. According to the Bartitsu Society, if you were approved, then you would take solo classes with an instructor before being permitted to join the group. From there, members would engage in circuit training between small groups and specialized instructors.

It fell into decline by 1902 for reasons not entirely known and closed its doors. The first issue was price: The fees were far too high. According to the Bartitsu Society, Barton-Wright was said to have issues with Yukio Tani, resulting in a physical fight. Martial Arts Studies reports Tani realized he could make more money since Londoners were interested in jiu-jitsu and departed to set up his own school. The other problem was that the public was more interested in jiu-jitsu itself rather than the hybridized martial art Barton-Wright was promoting, as the Martial Arts Journal speculates.

Bartitsu was Sherlock Holmes' fighting style

According to the Atlantic, bartitsu would have faded completely into obscurity were it not for a random reference Sir Arthur Conan Doyle wrote in "The Adventure of the Empty House." Holmes uses bartitsu to defeat his nemesis Professor Moriarty. The passage reads in part "... baritsu, or the Japanese system of wrestling, which has more than once been very useful to me" — notice that Doyle misspelled the name.

The fight scenes with Robert Downy Jr. as Sherlock Holmes depict him using the martial art in both his films. Director Guy Ritchie incorporated the most fundamental elements of the art into the fight choreography: the art of surprise and using the attacker's strength to your advantage.

According to Ritchie in a Vanity fair interview (via the Atlantic), "There's all sorts of locks and chokes and various other techniques used to incapacitate someone. There's lots of throwing hats at someone's eyes, and then striking at them, if you can, with a walking stick."

One only needs to watch the bare knuckle boxing scene in 2009's "Sherlock Holmes" to get an idea of what unarmed bartitsu would look like. Particularly viewers see how Holmes employs a handkerchief to distract his opponent before a series of strategic blows. He aims to confuse before launching the man to the ground with a kick. There is also a brief scene where Rachel McAdams' Irene Adler demonstrates defending herself with a hidden club and a knife against two muggers.

Ties to the British Suffragettes

Even though by the end of the 1890s British women had more freedom to engage in sports like cycling, tennis, golf, and fencing, it was rare for women to engage in any form of martial arts (via NYC Steampunk). The suffragette movement was a keen follower of the sport, as women would engage in civil disobedience promoting women's right to vote.

BBC reports these demonstrations escalated to violence due to the lack of progress. Members of the movement were getting arrested and disliked being manhandled by police and other people objecting to their marches, so they eventually formed their own group of bodyguards.

The most famous of them was a woman named Edith Garrud, who, along with her husband, trained with E.W. Barton-Wright (via Ozy). Garrud was a tiny woman under 5-feet tall, but she trained the suffragettes in the art of jiu-jitsu. In fact she and her husband took over former bartitsu instructor Sadakazu Uyenishi's London dojo.

The Bodyguard consisted of 30 women armed with clubs hidden in their dresses. According to the BBC, in one incident they rigged the stage of St. Andrews's Hall with barbed wire concealed by bouquets, and as soon as leader Emmeline Pankhurst began speaking, police rushed the stage. The Bodyguard fought back 50 policemen for a time before they were overwhelmed and arrested. This was merely one of many battles they fought against police.

E.W. Barton-Wright's post-Bartitsu years

What ever happened to Edward William Barton-Wright in the days after bartitsu declined? It was bad luck that judo and jiu-jitsu overshadowed his unique approach to self defense. After the club closed he focused his attention on being a physical therapist and established several clinics around London (via the Bartitsu Society).

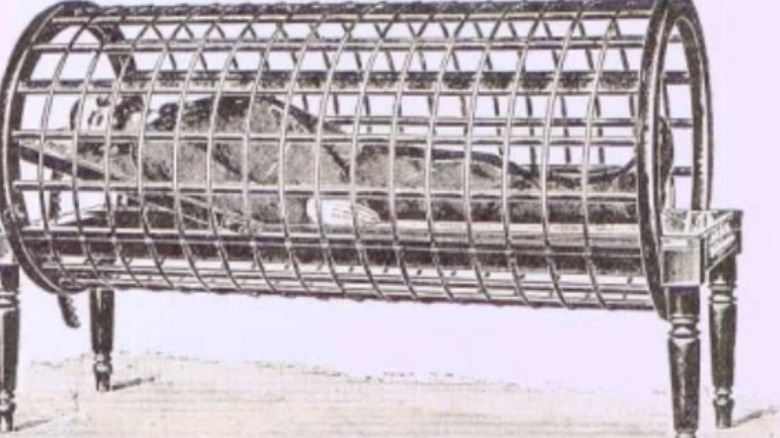

Barton-Wright's success in the medical field was met with intense skepticism, owing to his lack of formal medical training. His businesses struggled with frequent lawsuits and used questionable therapies (some led to harm). Some of his devices were early ancestors to the tanning bed and diathermy machine. He eventually came to specialize in treating rheumatism with heat and vibration.

He never truly received credit during his life for his role in bringing Japanese martial arts to England. Barton-Wright failed to regain the level of success he held during the peak of bartitsu. When he died in 1951, he did not have enough money for anything better than a "pauper's grave."

Thanks to careful research done by preservationist, Barton-Wright can be remembered as an innovator. He was one of the first Westerners to study Japanese martial arts and the first to promote and teach it in Europe. He was also the first to create a hybrid fighting style for street fighting defense decades before Bruce Lee would found Jeet Kun Do (another hybrid fighting style). One could say he was the first to blend mixed martial arts with Eastern and Western styles.

The legacy and modern revivals of the practice

It is still possible to learn the gentlemanly art of bartitsu around the world. Part of its preservation and revival is owed to Tony Wolf. Wolf is a fight choreographer, martial arts instructor, and founder of the Bartitsu Society (as per the Atlantic). Wolf has spent years along with other members researching and compiling martial arts manuals from the Victorian and Edwardian eras.

According to Wolf there are no accredited bartitsu masters, and each school interprets E.W. Barton-Wright teachings in their own way. Every school does adhere to three basic principles set by Barton-Wright in "How a Man may Defend Himself against every Form of Attack": "to disturb the equilibrium of your assailant"; "to surprise him before he has time to regain his balance and use his strength"; and "if necessary to subject the joints of any part of his body, whether neck, shoulder, elbow, wrist, back, knee, ankle, etc. to strain which they are anatomically and mechanically unable to resist."

The Bartitsu Society reports they approached the revival as a collaborative project that is always evolving, based on the idea that Barton-Wright had left the art as a work in progress. The organization wrote two books, "The Bartitsu Compendium" (as two volumes), and houses numerous resources for anyone wishing to start their own bartitsu school.