The Dark Origins Of The Grim Reaper

No two people share the same life experiences. Even those who grow up in the same house can have vastly different lives, and there are times that can make the world seem very, very lonely. There's one thing that ties everyone and everything together, though, and that's death.

That got dark pretty quickly, but it's true: At some time, death will come for family — beloved or otherwise — friends, coworkers, and those acquaintances you always meant to learn more about before it was too late. It'll come for our cherished pets way too soon, and the only way it'll stop taking those around us is when it comes and steals us away.

Didn't think it could get darker? Hold our beer.

Today, death is often personified as the grim reaper, a cloaked and skeletal figure wielding a scythe. It's ominous, sure, but it's been around so long that pop culture is just as likely to make a mockery of it as it is to depict it as the inevitable force of nature that it represents. While it might seem like one of those all-knowing, ever-present creatures that has been around since humankind first learned a very hard lesson about what death is, it's not nearly as old as might be expected. Surprised? Let's talk about the reaper man.

The very first depiction of an animated, skeletal Death

The grim reaper is a little different when it comes to the world's otherworldly creatures in that we know when and where the first depiction occurred. (Probably). In her PBS series Monstrum, Dr. Emily Zarka says that death as a skeletal harbinger first appeared in the 13th century illustration called "The Legend of the Three Living and Three Dead."

The illustration was based on a story of the same name, which predated it only slightly. (It, too, was from the 13th century.) It remained popular for centuries — the version that the Canterbury Cathedral has dates to the 16th century — and it's a pretty powerful tale.

There are a few different versions of the story, but in a nutshell, three men are hunting when they come across three corpses. The first is usually described as sort of freshly dead, the second has been subjected to quite a bit of decomposition and rot, and the third is only a skeleton. Still, they can all speak, and warn the three living men that life is fleeting, and they should take heed of the choices they make. Why? They were going to be corpses soon, too.

According to The British Library, the three dead showed up in scores of manuscripts, illustrations, and artwork — sometimes, in pieces commissioned by nobles that put themselves alongside the skeletal messengers. It was meant to serve as a graphic reminder that death comes for us all, so make life count.

The scythe shows up in the frescos of Pisa's cemeteries

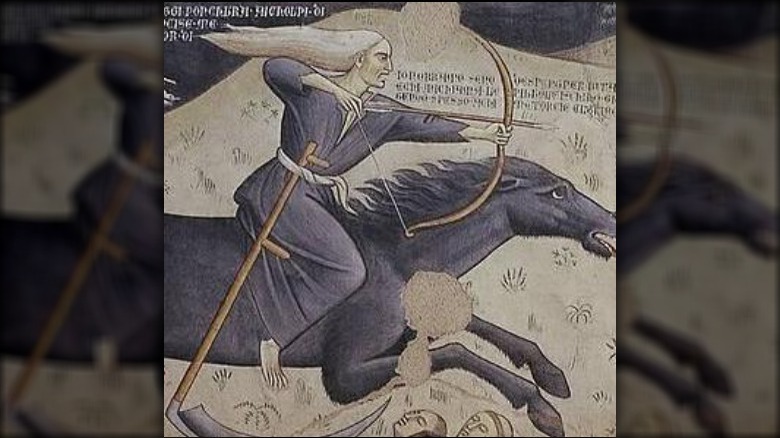

The image of the grim reaper as we know it today seems to have evolved in stages, with the first being the animated skeleton. Those personifications of death were missing a few things compared to the more modern depiction of the reaper, and according to what Dr. Emily Zarka says in the PBS series Monstrum, some of the earliest depictions of death wielding a scythe are found in the frescos of a cemetery in Pisa, Italy.

Art in Tuscany gives a fascinating look at the history of the cemetery and the frescos, saying that the entire burial complex was built beginning in 1278, and finishing some time in the 15th century. Constructed on an older burial ground over dirt shipped to Italy from the Holy Land, the first frescos were installed in the mid-1300s. The very first one was done by the painter Buonamico Buffalmacco, and it was called The Triumph of Death. It was inspired by "The Legend of the Three Living and Three Dead," but it showed a slightly different version of things. In his interpretation, the figure of death has long, flowing white hair, skeletal features, the wings of a bat, and is holding the now-famous scythe.

Death was originally female

Buonamico Buffalmacco's version of the grim reaper isn't entirely the same as the one everyone is familiar with today. According to The American Scholar, Pisa's Death not only harkened back to an ancient poet's description — "pallid Death ... knocks impartially on paupers' huts and the towers of the rich" — but was female.

With flowing robes and long, white hair, this early figure of Death was depicted as looking to the next set of souls she's going to take with her. Interestingly, it's believed to be characters from Giovanni Boccaccio's "Decameron," a story about a group of rich friends who decide to wait out the plague by leaving the city and heading to the countryside. Buffalmacco definitely could have read it, as it featured him in some of the stories.

His wasn't the only female Death: Cherwell speaks to an image on the walls of France's Priory of St. Andre. Standing amid piles of the dead is a lone woman, holding the arrows that delivered the plague to victims chosen with terrifying randomness.

So, when did Death become the traditionally male figure he is today? (With, of course, some notable exceptions like Neil Gaiman's female Death from "The Sandman.") By the mid-15th century, the figure of Death had become associated with this passage from Revelations: "And I looked, and behold a pale horse: and his name that sat on him was Death, and Hell followed with him."

The horse wasn't named Binky until much later.

When death was everywhere, people gave it a face

Now, a quick history lesson: Between 1346 and 1353, a plague that would later become known as the Black Death completely ravaged Europe. Death tolls are understandably difficult to come by, but Ole J. Benedictow, Emeritus Professor of History at Norway's University of Oslo, suggests that as many as 50 million people died, or around 60% of Europe's entire population.

Benedictow says (via History Today) that one of the ways the Black Death spread from North Africa, the Middle East, and Constantinople into Europe was through the Italian seaports of Venice, Genoa, and finally, Pisa.

And that brings us back to the grim reaper. It's in the frescoes of Pisa's cemeteries where some of the earliest imagery of the personification of Death show up, but according to The American Scholar, imagery of the grim reaper spread along with the plague.

The figure almost immediately started showing up in paintings and illustrations of the horrors that the plague brought. Death appears alongside entire families who died, in streets filled with corpses, and targeting the rich and the poor alike, a vivid reminder that as far as the grim reaper was concerned, everyone was equal.

Interestingly, early versions connected with imagery of the plague often showed Death on a horse (or now-familiar skeletal horse), firing or carrying a bow. That's not as random as it sounds, as the bow was the weapon of choice of Apollo, who often used arrows to deliver plague.

Skeletal versions of death were featured in the Danse Macabre

Medical historian and epidemiologist Thomas McKeown had an interesting take on medical advances. He believed (via The BMJ) that medicine should be more concerned with improving the quality of life, not the length of it — by helping people live longer, they were really just changing what horrible ways they died.

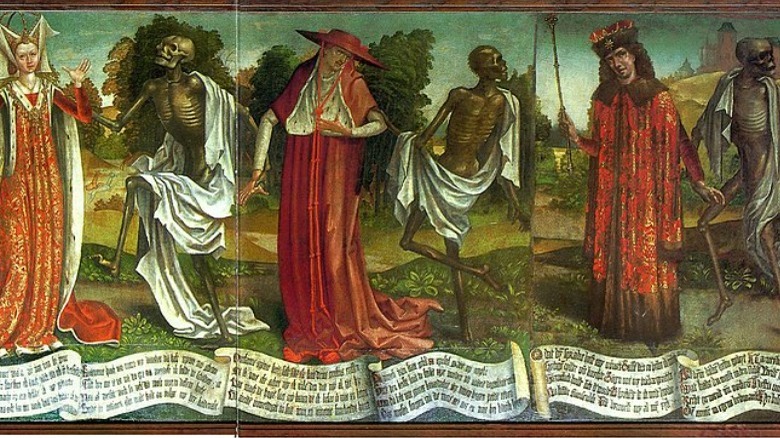

Centuries ago, death was seen as a perhaps more inevitable thing... as illustrated by the Danse Macabre. There are scores of different versions of this image, but the idea is the same: A dancing skeleton, appearing to the living to dance with them on the way to their graves.

According to Atlas Obscura, the very first appearance of the idea of Death appearing to dance with the living on their way to damnation was in a painting in the Cemetery of the Holy Innocents. The painting was installed in the Paris cemetery some time in the 1420s, and it depicted people from all walks of life in a long parade, with each one being escorted along by a skeletal reminder of their eventual end. The idea proved to be wildly popular, and spread across Europe in much the same way the idea of a singular, skeletal Death did. Countless versions expanded and adapted the idea.

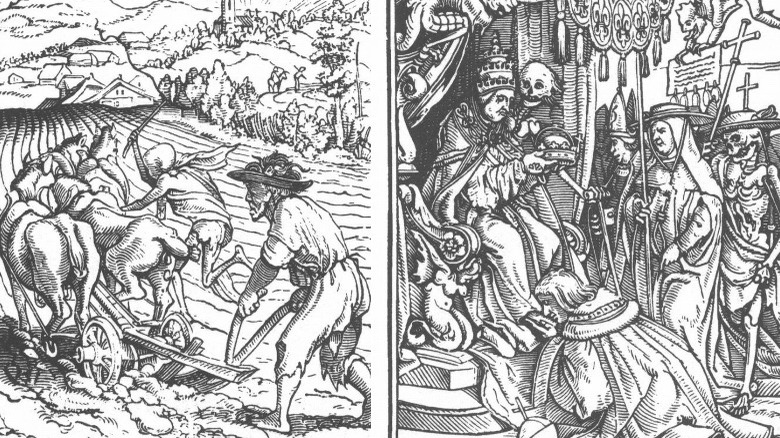

The Danse Macabre got a notable change with the work of Hans Holbein the Younger. His images show the skeletons not just escorting the living into the land of the dead, but taking lives themselves.

Death wasn't always something to fear

There's something terrifying about the grim reaper — regardless of what one might believe comes after, death is the end of the only life we know. That's the stuff of nightmares, but historically, the grim reaper wasn't always an entity to fear.

That's most noticeable, perhaps, in the works of Hans Holbein the Younger. Atlas Obscura says that he wasn't just an artist, but he was an outspoken opponent of the economics of his era, which were the 1520s (give or take). In his depictions of the Danse Macabre, skeletons and death coming for the rich and powerful were feared, because those were the people who lived a life of luxury, and had everything to lose. When the same skeletons came for the poor, though, they offered a release from back-breaking labor, starvation, and a life of servitude.

The BBC says that's a shift that became more pronounced throughout the 16th century. Even as the Black Death returned to Europe, the images of Death and the Danse Macabre remained a popular visual warning that death could be waiting around the next proverbial corner — for everyone. At the same time, artists like Marcantonio Raimondi were creating works that focused not just on the suffering of the individual, but on those people who risked their own lives to help their fellow men, women, and children. Images reminded everyone that death was coming for us all, and the thing that bound us together against it was empathy.

Artwork featured the emerging Triumph of Death motif

There's something comforting about the grim reapers of the Danse Macabre. Given that death is inevitable, there's not really a better way to think of it than being escorted off into the afterlife by a conga line of skeletons that have already made the journey. In that case, the grim reaper is playing escort — but, says Cherwell, there was a sort of parallel evolution to the grim reaper that made it clear that it's not all fun and games.

And, someone was going to do worse than just poke their eye out.

This movement started in earnest with Pieter Bruegel the Elder's "The Triumph of Death." Now one of the flagship pieces of the Museo Del Prado, it's dark stuff that's not only concerned with the random death brought by the plague, but also the death that humankind brings upon itself. Armored, sword- and spear-wielding troops are cut down indiscriminately on the battlefield, sliced to pieces and escorted to the afterlife by a grim reaper that swings a scythe from the back of a skeletal red horse.

The message of this — and other, similarly themed works — is clear: Death doesn't care what humans are fighting over. It's all inconsequential and it's definitely not important in the grand scheme of things, because he'll take it all. Even from the winner.

Northern Europe had a different version of the plague's death

While much of Europe seized on the image of the skeletal avatar of Death, Talk Norway says that Norwegian folklore had a different way of personifying the death and devastation that swept through the nation. The plague was given the shape of an old woman named Pesta — the word for "plague" — and it was said that she could be recognized by her red skirt.

As unlikely as it seems, Pesta is even more terrifying than some skeletons. The 14th century story says that Pesta traveled from town to town, and those who found themselves in her path could tell how many lives she was going to take. If she had a rake, it was possible that she would catch some, but others would slip through. If she had a broom, there was nowhere to hide and no one would avoid being swept away.

She wasn't without compassion, though. There's one story that said she hired a man to take her across the lake in his boat. He didn't immediately recognize her, but when he did, he begged her to spare his life. She didn't answer right away, and instead, she looked through the pages of the massive book she carried before telling him that she couldn't spare him. In return for his kindness in giving her a ride, though, she promised him that his death would be painless. It was: He went home, fell asleep, and never woke up.

He wasn't called The Grim Reaper for centuries

So, here's a question: Humankind has always known "Death" as "The Grim Reaper," right? Not exactly, and according to Dr. Emily Zarka (via Monstrum), giving Death the moniker of The Grim Reaper is an almost shockingly recent invention.

First, a fun bit of word history. The Online Etymology Dictionary says that the word "grim" has roots in Old Norse and Proto-Germanic languages, and was first used in the 12th century. (Zarka gives a slightly different date of the 10th century.) It originally meant something along the lines of "gloomy," which makes for an interesting take on the so-called reaper.

And what about "reaper"? That, they say, goes back to Middle and Old English words that appeared in the 14th century, and they add that it wasn't until 1818 that the word was first used to describe death. "Grim reaper" took even longer to come about, and Zarka says that the first use of the term was in a 1847 text called "Circle of Human Life." It was the Rev. Robert Menzies who wrote, "All know full well that life cannot last above seventy, or at the most eighty years. If we reach that term without meeting the grim reaper with his scythe, there or there about, meet him we surely shall."

The ancient Egyptians had their own personification of death

The grim reaper certainly isn't the first time humankind has tried to give the inevitability of death a form that made it a little more understandable. For the ancient Egyptians, they had Anubis, the jackal-headed god of the afterlife and lost souls.

According to World History, it's believed that Anubis was given his distinctive appearance for a very specific reason: They had hoped to appeal to a canine-inspired god in order to discourage wild dogs that had a nasty habit of digging up the recently dead.

Anubis doesn't just represent the inevitability of death, but he also embodies the prospects of resurrection. Much like the more benevolent version of the grim reaper that developed later, Anubis existed to protect the dead on the spirit's journey through the afterlife, and there's something comforting about the thought that no one had to go through it alone. In addition to Anubis, they also had his daughter, Qebhet: Her place in the pantheon was to comfort troubled souls having difficulty adjusting to their demise.

The dead were known as westerners, as it was believed that souls traveled into the west — and into the setting sun — after they passed. He was also said to sit at the head of an army that would descend with vengeful wrath upon anyone who desecrated burial places or remains. Even after Osiris displaced him in the pantheon and his story changed, he remained a faithful protector of the dead.

The ancient Greeks had Thanatos, a beautiful version of death

Ideas about the personification of death morphed a little further with Thanatos, the ancient Greek spirit of non-violent deaths. (Violent deaths, says Theoi, happened under the guidance of Thanatos' sisters.)

Dr. Emily Zarka says (via Monstrum) that our version of the grim reaper draws a lot from the Greek Thanatos — who, interestingly, was the twin brother of the personification of sleep, and the son of Nyx, the night. He's recognizable in ancient artwork because he's associated with two distinctive symbols: an upside-down torch, and a butterfly.

That's a far cry from the scythe-wielding grim reaper, but Zarka suggests there's another connection to be made here. She says it was the Titan Kronos who was also used as a bit of inspiration for the personification of death. He's most famously known for eating his own children — including Zeus — in hopes of preventing them from killing him, but he was also a scythe-wielding god of time. Once he was forgiven by his son and released from his prison, he was granted a realm of his own: He became the ruler of the Elysian Islands, the final home of the good, the worthy, and the righteous.