How Mary McLeod Bethune Changed History

In the nearly 250-year history of the United States, there have been some remarkable individuals, men and women who stepped up, stood out for their accomplishments and contributions to creating a better society. Schools generally teach a lot about men like George Washington, Ben Franklin, Abraham Lincoln, or Thomas Edison. While these figures are obviously important to the history of America, there are many other people who are sometimes skipped over, though their impact on the nation are highly important as well. One of those people is Mary McLeod Bethune (per Biography).

During the early part of America's history, the rights of women and people of color were extremely limited. As a Black woman in 19th century America, Bethune found that her freedoms were pretty restricted. However, she did not let any of that stop her as she became a legendary educator and civil rights activist, seeking to change the way society treated both women and people of color.

Early life

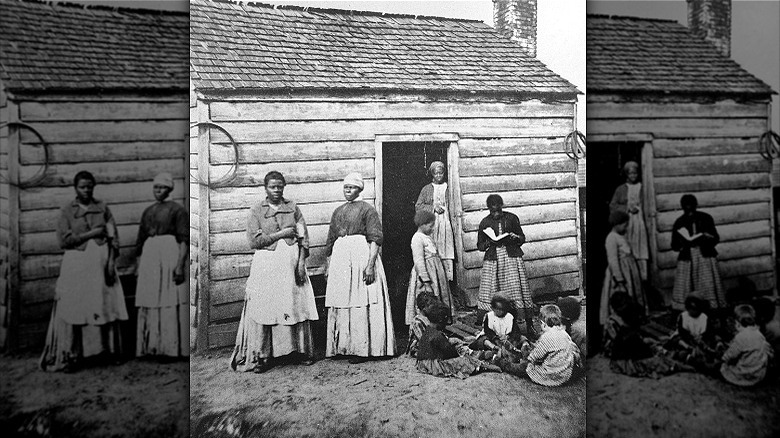

According to National Women's History Museum, Mary Jane McLeod was born on July 10,1875 in South Carolina. She was one of 17 children born to Samuel and Patsy McLeod, both of whom had been enslaved. Following the Civil War, McLeod's mother continued to work for the man who had enslaved her in order to earn enough money to purchase land for her family. None of the children were exempt from working and they all picked cotton on their family land.

McLeod's life was forever changed when she became the only child in her family who got the opportunity to go to school (per Biography). A missionary opened a school for African American children miles away from her home, but the distance didn't stop her. She walked to and from school every day and also attempted to share all that she was learning with her beloved family. This start to her education allowed McLeod to later pursue higher education at multiple institutions, including Scotia Seminary and Moody Bible Institute.

Contributions to education

McLeon attended and graduated from what later became Barber-Scotia College in Concord, North Carolina. She also attended what later became Moody Bible Institute, with aspirations to becoming a missionary in Africa, but she was denied that opportunity by the Presbyterian Missionary Board (per National Park Service – NPS). McLeod returned to South Carolina, where she used her knowledge to become an educator. While working as a teacher, she met and married Albertus Bethune, who was also a teacher, in 1898 (per NPS). The couple had a son the following year and then moved to Florida, where Bethune opened a missionary school. Unfortunately, she and her husband separated after that, but that didn't keep her from pursuing her goals.

Five years after opening her first school, Bethune then opened the Daytona Educational and Industrial Institute in Daytona, Florida, as a school for African-American girls. Originally modeled after the Scotia Seminary, Bethune used her business savvy to expand the school over the years. She managed to procure funding from philanthropists like James M. Gamble and John D. Rockefeller, and by 1918 her little elementary school of six students had expanded to include a high school as well.

Like many schools for African Americans during this time, this institution had a heavy focus on religion, homemaking, industrial education, and agriculture (per NPS). By 1920, 47 young women had graduated from the high school — impressive numbers for those time. The school later merged with the Cookman Institute to become a co-ed college, which Bethune was president of from 1932 to 1947.

Activism

You would think that trying to single-handedly change the face of African-American education would be enough of a challenge for anyone to take on. For Mary McLeod Bethune, however, her accomplishments in education, while impressive, were not enough for her. She took on more adversity when she became an activist for both women and minorities.

According to Biography, Bethune contributed to American society in various capacities. She was the president of the National Association of Colored Women for years before using her expertise in multiple roles in government. She served under many presidents, including Herbert Hoover, Calvin Coolidge, and Harry Truman. Her most notable contribution, however, happened when she worked with President Franklin D. Roosevelt.

In 1935 Bethune became President Roosevelt's advisor on minority affairs and started her own civil right organization the same year, the National Council of Negro Women. The following year she was also appointed director of the Division of Negro Affairs of the National Youth Administration. Bethune was a trusted advisor and friend of both FDR and his wife, Eleanor (pictured with Bethune, above) and also eventually became an early member of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People.

Accomplishments

Mary McLeod Bethune clearly accomplished many things in her life, so it would be hard to choose the most impressive one. However, one of the most recognizable achievements in her life was helping to establish The Federal Council of Negro Affairs during FDR's presidency. This council consisted of prominent African Americans who served as advisors to President Roosevelt during his presidency and also became widely known as the Black Cabinet (per ThoughtCo).

In addition to literally being one of the president's most trusted advisors, Bethune also received multiple honors during her life. In 1935, she was awarded the Spingarn Medal (per Britannica) by the NAACP for her achievements. A decade later, in 1945, she was the only African-American woman to help represent the United States at the founding of the United Nations. During the 1950s she was also appointed to the committee on national defense under President Harry Truman, and was the U.S. representative at a presidential inauguration in Liberia.

An amazing legacy

Bethune technically retired in 1949, though she still remained active in the country's politics. She still traveled, gave speeches, and worked tirelessly to provide more opportunities for the African-American community. According to NPS, Mary McLeod Bethune passed away at her home in Florida on May 18, 1955, after suffering a heart attack.

The legacy that this woman left behind is immeasurable. She provided access to education to the African-American community in the South, during a time when this was nearly impossible. In addition to the education she helped provide for decades, her work with the government opened doors to more jobs, skilled trade training, and equal treatment for African-Americans in society as a whole. With as many things as things as she accomplished in her life, it is hard to just focus on one, but Mary McLeod Bethune broke all kinds of barriers and helped pave the way toward true equality for all Americans.