The History Of Perfume Explained

In 1939, the Nobel prize for chemistry was won by Leopold Ruzicka, a Croatian scientist with a passion for understanding the composition of natural substances. Ruzicka spent many years working in perfumery, studying the chemical compounds responsible for fragrances and working with molecules like jasmone and linalool, which contribute to the fragrances of jasmine flowers and citrus fruits. From his work, Ruzicka had a deep understanding of the intimate relationship between perfumes and modern chemistry. As a presentation at the 2015 International Workshop on the History of Chemistry explained, he noted how "right from the earliest days of scientific chemistry up to the present time perfumes have substantially contributed to the development of organic chemistry."

The history of perfumes and fragrances is intertwined with all of recorded human history and, as Leopold Ruzicka rightly pointed out, it's linked with many scientific processes which are now essential parts of 21st-century society. The process of distillation, for instance, is used in processes as varied as desalination of seawater and creating alcoholic spirits – a process which, as 1001 Inventions explains, was perfected by Islamic scientists in the 14th century for the creation of perfumes.

According to Britannica, perfumery was part of a number of ancient civilizations as varied as the Chinese, Arabs, Romans, Hindus, and Egyptians. Even the word perfume derives from the Latin phrase per fumus, which literally translates as "through smoke." An apt meaning, as some of the earliest perfumes in history were used in incense.

4000 Years of Fragrance

The oldest perfumes ever discovered by archaeologists were unearthed in the ancient ruins of Pyrgos on the Mediterranean island of Cyprus. A 2007 National Geographic article explains how the ruins contained an entire perfume factory, with stills, mixing jugs, and a variety of perfume bottles. From traces of the ancient perfumes, scientists managed to identify 14 distinct fragrances used in making ancient perfume, containing plant extracts including anise, bergamot, almond, and parsley.

Following the find, scientists recreated the ancient fragrances, presenting them at an exhibition in Rome in 2007. NBC News reports on this, explaining how the ancient perfumes were rather different from those enjoyed in the modern world. The Ancient Cypriots eschewed floral aromas, favoring the fresh scents of herbs and spices. They also used a base of oil rather than the alcohol used in modern perfumes. According to the Deccan Chronicle, the scents of Ancient Cyprus were renowned because of the high quality of olive oil used in their manufacture. These perfumes were considered a symbol of life, making them very important in the ancient world.

An interesting aside to this discovery is the fact that, in Greek mythology, Cyprus is known as the birthplace of Aphrodite, the goddess of love, lust, and beauty. Archeologists speculate that the island's fame as the source of ancient perfumes may tie in with this. Cypriot perfumery is seemingly older than the legends of Aphrodite, and, with their use between lovers, the perfumes remained linked to Aphrodite long afterward.

The Fragrance of Ancient Egypt

Some of the first perfumes were used in Ancient Egypt and, as Tailor Made Fragrance explains, some people credit the Ancient Egyptians with the original invention of perfume. The Egyptians used a variety of essential oils, resins, and fragrant unguents which were first used in their religion. These scents were part of ceremonies and prayers, and were also used to convey messages to the dead. According to McGill Office for Science and Society, fragrant resins like myrrh and frankincense were popular in Ancient Egypt, and these were among the goods widely traded at the time. The Egyptians would have had access to incense imported from places like Arabia and India, enjoying them so much that they'd eventually begin to use them in daily hygiene as well as in worship.

A commonly used Ancient Egyptian fragrance is known as kyphi, though as Ancient Egypt Online notes, the original name for it was kapet. Archaeologists have found a few surviving recipes for kyphi which usually included cinnamon and resins like pine and mastic, as well as herbs like mint and camel grass. Kyphi was widely used as a temple incense, as well as a medicine. Even in Egyptian society, this fragrance had a long history, with the earliest known mention of it coming from the pyramid texts, dating back over 4300 years.

Tapputi of Mesopotamia

The history of perfumes is closely linked with the history of chemistry, and the earliest known chemist in recorded history was a Babylonian woman named Tapputi, who lived around 3200 years ago. According to Cosmos Magazine, her full recorded name was Tapputi-Belatekallim, with "Belatekallim" referring to her as the head of her household. In Ancient Mesopotamia, much like in Egypt, perfumes were an important part of society, used in medicine and religion as well as for cosmetic purposes. The chief perfumier for the royal palace of Babylon, Tapputi was an important figure in society, using her skill in chemistry to formulate fragrances for the king. One of her royal recipes survives to this day, recorded in cuneiform tablets. A fragrant ointment made with flowers and calamus mixed with water and oils.

The book "Women Encounter Technology" elaborates further on how the chemistry techniques used by Tapputi wouldn't be unfamiliar to scientists in modern laboratories. The methods of distillation, extraction, and sublimation were pioneered in the Babylonian perfume industry. As a paper in the journal Osiris mentions, Tapputi wasn't the only woman in charge of creating Ancient Mesopotamian perfumes. Surviving texts also mention another woman, known only as Ninu the Perfumeress. Sadly, her full name has been lost because the first half of her name is missing from the tablet which mentions her.

Attar and the Indus Valley

Alongside Egypt and Mesopotamia, the third of the world's earliest known societies was the Harappan civilization of the Indus Valley, and they too had a flourishing perfume industry. As an article in The Atlantic notes, clay distillation pots have been unearthed from Harappan ruins dating back thousands of years. These were used to make fragrant oils known as attars which have been enjoyed in South Asia ever since, from the 15th-century rulers of the Mughal Empire to people across modern-day India.

The people of the Indus valley evidently valued perfumes just as highly as their neighbors in Egypt and Mesopotamia, as ornate perfume bottles have been discovered there. These are sometimes sold to collectors, as attested by the archives on Live Auctioneers. Dating back roughly 4500 years, these items show that the Harappans rivaled the Egyptians in early perfumery. As Karnataka Aromas explains, the Indus Valley's knowledge of distillation dates back to around 3000 BCE, making their terracotta vessels some of the world's oldest.

An Ancient Trade of Silk and Perfume

On the other side of Asia, the Ancient Chinese also placed a high value on perfumes. As ECNS explains, China has had a tradition of using fragrances since neolithic times, and a paper in the Chinese Journal of Medical History describes in detail how the use of fragrances in Ancient China dates back to before the Qin period, when perfumes had therapeutic and religious uses. As in Ancient Egypt, the use of perfumes in Ancient China evolved over time. By the Three Kingdoms period, perfumes were used widely among the more prominent members of Chinese society to fragrance clothing and homes. The Floristry notes that perfumes in Ancient China were regarded as ways to disinfect and purify public spaces, and were used to ward off disease.

As perfumes were more widely used for cosmetic purposes in Ancient China, many people carried silk perfume pouches known as xiangbao. These multipurpose accessories were used to fragrance someone's body as well as to repel insects and keep evil spirits at bay. As the popularity of perfumes grew in Ancient China, they became widely traded along the ancient trade route known as the Silk Road. Crossing from Xi'an in China all the way to Ancient Rome, fragrant herbs and spices were popular luxury items. ECNS notes how these were often imported to China during the Han Dynasty, and continued to be important in the later Tang and Song Dynasties too.

Roman Decadence

The Ancient Romans were famously decadent and hedonistic and, as might be expected, they made liberal use of perfume. The Romans placed great importance on hygiene and personal care and, as the Perfume Society explains, perfumes featured prominently in Roman public baths. Fragrant oils and lotions were used to scent peoples' skin and hair, and Emperor Nero was even known to fragrance public spaces.

Not everyone in Rome was quite so extravagant, however. The philosopher Pliny the Elder was known to condemn the excessive use of perfumes as wasteful and superfluous luxuries. Notwithstanding his opinions on them, however, Pliny's writings are part of the reason why so much knowledge about the Roman love of perfumes survives to the modern day. A Getty blog post discusses this, explaining how Pliny wrote about perfumes in his book, "Naturalis Historia." It contains details about the sophisticated methods used to create Roman perfumes, from ingredients to the techniques and tools used in their preparation. As in other ancient cultures, perfumes were particularly important in Roman temples, which often had nearby perfume factories to supply them with sweet fragrances on demand.

Arabia, the Land of Perfume

With the fall of Rome, perfumes also fell out of favor in Europe. According to Officina Delle Essenze, this was linked with the rise of Christianity, which aimed to erase all old associations with pagan traditions, particularly considering the prolific use of perfumes in the temples of older cultures. Most people stopped working in perfumery, out of fear of potential consequences. Elsewhere, however, perfumery continued in abundance.

According to the Museu Del Perfum, Southern Arabia became known as the Land of Perfumes. While perfumes were no longer made in Europe, there was clearly still a demand for them, and sweet fragrances from Arabia were exported all around the Mediterranean. The Arabs built on the knowledge of older cultures, developing new techniques of their own. The most popular fragrances of the middle ages, rosewater, musk, and civet, were prepared abundantly by Arab perfumiers. This tradition continued with the rise of Islam, when perfumes became highly valued in worship. A paper in the journal Arabica discusses how perfume and incense were highly valued at Muslim pilgrimage destinations, with the scents themselves being an important part of the experience.

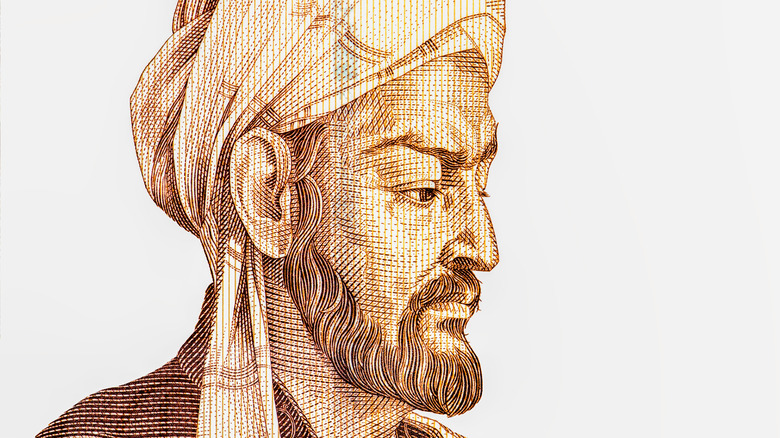

Al-Kindi, the Father of Perfume

One of the most influential figures in the history of perfume was an Islamic philosopher named Al-Kindi. Born in the Abbasid Caliphate in the early years of the Golden Age of Islam, Al-Kindi studied in Baghdad before going on to become one of the most prominent polymath scholars of his time. It was his contribution to the study of fragrances, as The Perfumist explains, which would earn Al-Kindi the epithet The Father of Perfume.

Al-Kindi, like many other perfumiers, was a skilled chemist. He was one of the first to dispel the idea that base metals could be transformed into gold, and was the first person to distill pure ethanol from wine. Perfumes and fragrances were one of his greatest interests, however, and he wrote prolifically about his research. The writings he left behind include a book called "The Chemistry of Perfume and Distillations," which contains hundreds of recipes for perfumes and fragrances.

Al-Kindi's work was helped by another Muslim chemist, Jabir Ibn Hayyan, who developed improved techniques for distillation, filtration, and evaporation – all essential for Al-Kindi's studies on plant-based substances. Daily Sabah discusses how Ibn Hayyan's work helped Al-Kindi to use plant extracts to create a variety of perfumes, as well as cosmetics and medicines. The methods pioneered by Al-Kindi in the 9th century are essentially the same as those still used in the modern cosmetics industry.

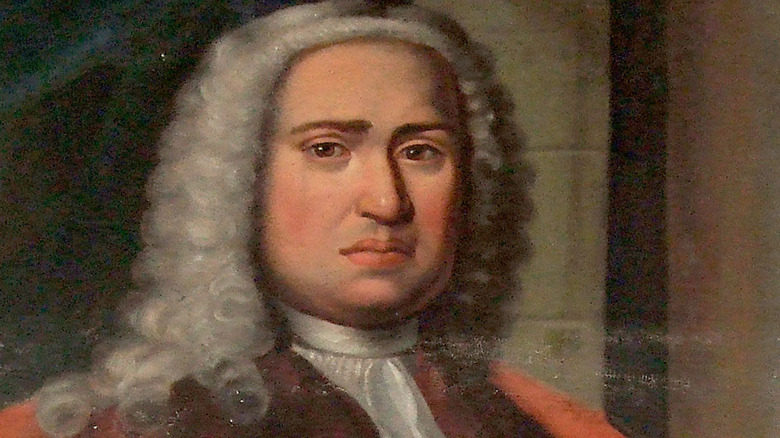

Avicenna's Love of Roses

Following in the footsteps of Al-Kindi, another Islamic philosopher would go on to become far more famous. His name was Ibn Sina, but he's most commonly known today by his Latinized name of Avicenna, a Persian scientist and philosopher who's widely regarded as one of the founders of modern medicine. As Daily Sabah notes, it was Avicenna who developed a way to extract flower oils by distillation – a process which, according to Artisan Aromatics, is still widely used to create essential oils today.

The book "Aromatherapy: Scent and Psyche" explains that, while distillation was already used previously, it was Avicenna who perfected the technique. This was used to produce floral waters, like rose water which was widely exported. The distillation techniques used by Avicenna would pave the way for fragrances to be based on alcohol rather than oil, as with modern perfumes.

Avicenna's work was mainly focused on medicine and pharmacy. A paper in the journal Natural Product Communications explains how he held a firm belief in the therapeutic effects of rose fragrance, believing it to be beneficial to the heart and brain, boosting cognitive ability. Rose products were used in medicines since Al-Kindi, and Avicenna worked to continue this tradition. Through his work in chemistry, Avicenna would go on to influence both modern medicine and perfumery.

The World's Oldest Perfumery

In the modern world, the oldest running perfumery is the Officina Profumo-Farmaceutica di Santa Maria Novella in Florence, Italy. Long after European Christianity had purged the "pagan" traditions associated with creating perfumes, Santa Maria Novella was founded by a monastic order in 1221, home to a botanical garden that they used to create medicines and ointments. The Dominican friars of Santa Maria Novella went on to play a leading role in European perfumery. They still produce perfumes and candles today, as they have for centuries.

The monks of Santa Maria Novella used the same methods as Al-Kindi and Avicenna, creating fragrant flower waters which were used as antiseptics. Smithsonian Magazine explains how they went on to play an important role during the 14th century's outbreak of the Black Death. As Europe struggled with the plague, the Santa Maria Novella monks ran an infirmary, treating people with the herbal remedies made by the monks. They also produced rose water, which they prescribed as a way to cleanse homes after outbreaks of plague.

The Queen of Perfumes and Poisons

Florence was an established center of the European perfume industry by the time Catherine de Medici was born in 1519. She would eventually leave Italy to marry into the French nobility, where she popularised the use of perfume in France. She also became a controversial figure in French history, famous for political intrigue.

This former Queen of France is, as Life In Italy notes, often associated with brutal assassinations and poisonings. Historians still argue about whether or not she was really behind the political atrocities she was accused of, but agree that she introduced a new level of elegance to the French court with her love of perfumes. She was also known for wearing a pair of perfumed gloves. According to legend, the jewelry she wore was carefully created to contain poisons that she'd use to murder her enemies, and the gloves were scented to hide the smell of any lethal toxins. In reality, it's likely she just wanted to mask the smell of the leather her gloves were made from.

Catherine also hired a personal perfumier, named René the Florentine. According to The Florentine, René was an orphan, raised by the alchemist monks of Santa Maria Novella. He went on to win the favor of Catherine de Medici by creating a bespoke fragrance with bergamot, which he named Acqua della Regina, "water of the Queen." He went on to open a wildly successful boutique in Paris, despite rumors of being the Queen's poisoner.

The Queen of Hungary's Water

Modern perfumes are alcohol-based fragrances, and one of the first to gain popularity was a 12th-century scent known as "Hungary Water" or "The Queen of Hungary's Water." A paper in the International Journal of Medicine and Pharmacy notes how this was created for Queen Elizabeth of Hungary around 1370. A recipe for this fragrance can be found in the 17th-century manuscript, "A Plain Introduction to the Art of Physick," describing a distillation of rosemary flowers in a round flask known as a curcubit. Having been written centuries later, however, it's hard to say how authentic this recipe is.

There's still some dispute over what exactly the original recipe for Hungary Water was. Materia Aromatica explains how the truth of the story is shrouded in rumor and legend. A popular story goes that the perfume was invented for the Queen as an anti-aging serum, created by her court alchemist to preserve her good looks. According to the tale, this kept the Queen so youthful that, even at the age of 70, a 25-year-old duke asked for her hand in marriage. Whether or not this story is apocryphal, one thing is certainly true – the Queen of Hungary's Water became a much-loved fragrance in Europe, wildly popular by the 17th century. It would remain Europe's favorite perfume until the creation of a fragrance that would eventually become far more famous. Eau de Cologne.

French Perfume, German City, Italian Perfumier

Eau de Cologne is arguably one of the most famous perfumes in the modern world, and the reason why men's perfumes in 21st century America are often referred to as colognes. While it has a French name, the city of Cologne lies in Germany, where it's known as Köln, and the scent was invented by an Italian. The South China Morning Post tells the story of how, in the 17th-century, apothecary Giovanni Paolo Feminis moved to Cologne to seek his fortune. There, he invented Eau de Cologne but, surprisingly, it was originally intended to be used not as a perfume but as a medicinal drink.

The famous fragrance wasn't even known as Eau de Cologne to begin with, according to Sillages Paris, being originally named Aqua Mirabilis. A fragrant concoction of citrus and aromatic herbs, Feminis's recipe was later developed and refined by his grandson, Jean-Marie Farina, who made his version into a perfume, adding the scent of bergamot. Farina reportedly said that he created the perfume as a fragrance that reminded him of spring mornings in Italy, of blossoms after the rain.

With its light, fresh aroma, Farina's fragrance rapidly gained popularity in Europe. It eventually became popular with the French army, who brought it to the Court of Versailles under the name Eau de Cologne. It was in Versailles, in the court of Louis XV, where Eau de Cologne would rise to its current level of fame.

The Perfumed Court of France

King Louis XV of France famously loved perfumes. He was so infatuated with flamboyant fragrances that, during his reign, the Court of Versailles became known as the perfumed court. The Chateau de Versailles is famously one of the most ostentatious places in Europe, and the French royalty who lived there led lifestyles to match. As Getty blogs explains, Louis XV's mistress, the Marquise de Pompadour, shared her lover's passion for perfumes, spending an extravagant amount of money on perfumes every year. Her budget would later be dwarfed by Queen Marie Antoinette, the wife of Louis XVI, who spent the equivalent of $32 million on perfumes each year.

As a result of the colossal demand for French perfumes, an expansive flower-growing industry blossomed in the South of France. As Complete France discusses, this industry was centered around the town of Grasse and has remained there ever since. Today, Grasse is often known as the world capital of perfume, as explained by an article in Fargo-Moorhead Forum (via NDSU). Many of the world's most famous perfumes, like Chanel and Giorgio, are still made in Grasse. In the 21st century, according to Global Newswire, perfumes have grown into a multi-billion dollar worldwide industry. Even after thousands of years of history, humanity is just as enamored with beautiful fragrances as it always has been