Chilling Details About The Russian Nuclear Disaster You've Never Heard Of

When it comes to nuclear disasters in the Soviet Union, the Chernobyl disaster is often the first one to be mentioned. But 30 years before the Chernobyl disaster, residents of the Soviet Union experienced a nuclear disaster that was covered up almost as quickly as it occurred.

Known as the Kyshtym disaster or the Mayak disaster, at the time it was the worst nuclear disaster that the world had ever experienced. But neither the world nor the residents at the epicenter of the disaster really knew what was happening at the time. It would take at least 20 years for news of the disaster to reach the international community. And even then, many officials outside and within the Soviet Union continued to deny that a disaster ever took place.

Even in the 21st century, information about the Kyshtym disaster is hard to come by because there were so few reports made about it at the time in an attempt to keep the disaster a secret. Meanwhile, the full extent of the disaster remains unknown to this day, since it's difficult to determine whether illnesses are caused by radiation poisoning or not. But with the staggeringly high rates of illnesses in the area, it's hard to pretend nothing happened. These are some chilling details about the Russian nuclear disaster you've never heard of.

Chelyabinsk-40

The Soviet Union started building the closed town of Chelyabinsk-40 in 1946, later renaming it to Chelyabinsk-65, though it was located over 50 miles from the actual city of Chelyabinsk. The Guardian writes that the town was constructed secretly around a nuclear power plant and housed workers from all across the Soviet Union who were tasked with building an atomic bomb. After two years of construction by almost 35,000 soldiers, POWs, and Gulag prisoners, the town's plutonium power plant, known as the Mayak Production Association, was activated in 1948.

Workers at the nuclear plant weren't allowed to leave the city or make contact with anyone outside for at least eight years. Families of the workers were simply led to believe that their relatives had vanished into thin air. According to "Man-Made and Natural Radioactivity in Environmental Pollution and Radiochronology," edited by Richard Tykva and Dieter Berg, during the first five years, workers were given absolutely no protection from radiation "in order to make up for the loss of time gained by the USA in the nuclear weapon techniques race." And even when radiation protection was finally introduced, it was woefully inadequate, with over 17,000 workers receiving radiation overdoses.

By 1949, the Mayak plant produced enough plutonium to develop a nuclear device. Tested at Semipalatinsk Test Site on August 29, 1949, the power of the explosion was equal to 22 kilotons of TNT, 7 kilotons more than the Hiroshima bomb.

Dumping toxic waste

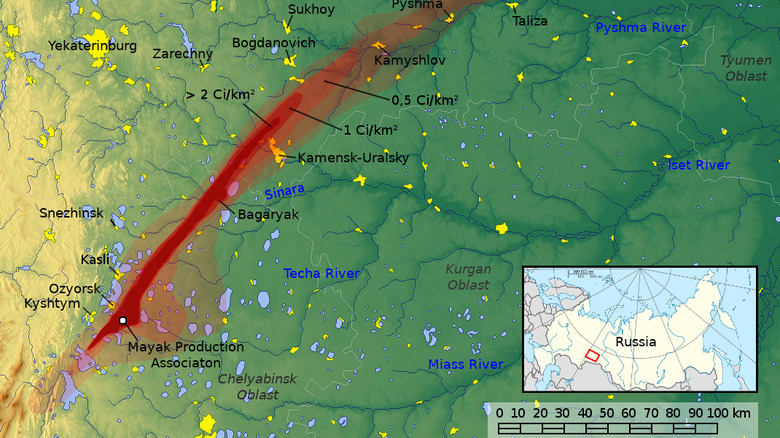

Before the Kyshtym disaster of 1957, there were numerous nuclear waste contaminations due to the Mayak plutonium plant. In 1949, Soviet workers started dumping waste from the nuclear plant into the Techa river, and over the next seven years, over "76 million cubic meters of liquid waste with a total activity of about 2.75 million Ci [curies]" was dumped into the Techa river, according to The Techa River by Dmitriy Evlanov.

The liquid waste flowed into Lake Kyzyltash, which quickly became incredibly contaminated. After it was noted that the Techa River was "exceedingly polluted," Lake Karachay started being used as a disposal site as well. Mother Jones Magazine reports that due to the nuclear waste dumping, Lake Karachay has accumulated 100 times more strontium-90 and cesium-137 than was released during the Chernobyl nuclear accident, making Karachay the "most polluted spot on Earth." "Man-Made and Natural Radioactivity in Environmental Pollution and Radiochronology" writes that at least 124,000 people were exposed to radiation due to the dumping of nuclear waste and at least 7,500 people from 20 villages were evacuated due to the radioactivity.

In 1986, Soviet scientists who had secretly studied the effects of radiation on the nearby population found that people living on the Techa River "had significantly increased death rates and cancers that occurred two to three times more frequently than among Japanese bomb survivors," John Perry writes in "Nuclear Weapons and the Environment."

The Kyshtym disaster

In addition to dumping nuclear waste in the nearby rivers and lakes, the Mayak nuclear plant also stored nuclear waste in an underground tank. But on September 29, 1957, the underground tank suffered a catastrophic explosion, resulting in the worst nuclear disaster the world had experienced up to that point, almost 30 years before the Chernobyl disaster. The explosion was caused by a failure of the waste tank's cooling system, but by the time anyone noticed it was too late. Mental Floss writes that the explosion of the nuclear waste tank led to a cloud of radioactive material that covered an area of over 7,500 square miles, spreading 2 million curies of radiation.

According to the Environment & Society Portal, people in the Chelyabinsk district started noticing bluish-violet colors in the sky. The local media wrote about the possibility of seeing the Aurora Borealis but as government officials descended upon the region, it became clear that this was no mere natural phenomenon. People were told to kill their livestock, bury their crops, and plow the farmland.

Freezer Box writes that children and young adults were recruited as liquidators to clean up the affected areas and tasked with burning crops, burying animals, and cleaning buildings. Some records state that at least 1,800 schoolchildren were recruited. And while official authorities wore white protective suits, the children and young adults who worked as liquidators were given little-to-no protective gear. Some ended up losing their hair during the cleanup work.

Evacuations

Over 270,000 people lived in the area affected by the radioactive cloud, but only 11,000 people were evacuated from over 20 nearby villages. Meanwhile, the evacuated villages were subsequently destroyed by Soviet officials.

In History of radiation and nuclear disasters in the former USSR, M.V. Malko writes that although Soviet officials knew that they had to evacuate people immediately, they had to wait for permission from Moscow, which came eight hours after the accident. Some of the most contaminated areas like Berdyants, Saltykovo, and Galikaevo were evacuated seven to ten days after the accident, by which point the residents had already received dangerously high doses of radiation. But in some affected areas, it took almost two years for evacuations to occur, writes SciHi Blog. During the evacuations, officials weren't allowed to explain the real reason for the evacuations. It was even forbidden to use the word "radiation."

In the village of Korabolka, over 300 people died in the immediate aftermath, according to Freezer Box. In response, Soviet officials evacuated only the ethnic Russian people from the village while the ethnic Tartar people in the village were ignored and left behind. Gulchara Ismagilova, a resident of Korabolka, states that "We were left here as a medical experiment. What other explanation is there?"

Covering up the disaster

After the accident, Soviet officials did their best to cover up reports of the accident, even keeping information from high-ranking state authorities. Malko writes that only a small number of the highest officials were informed of the accident and only some of the deputies of the Ministry of Internal Affairs of the USSR were told about the accident. Even "the majority members of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union did not receive any information about it."

Bellona writes that the name, the Kyshtym disaster, was also intended as a misdirection. Kyshtym is located over five miles away from what was Chelyabinsk-40 and Soviet officials claimed there had been an explosion at a non-nuclear power plant in Kyshtym in order to focus attention there. According to The Calvert Journal, the accident was deliberately covered up so that Soviet officials could preserve the reputation of their nuclear program. According to "Nuclear Wastelands," edited by Howard Hu, Arjun Makhijani, and Katherine Yih, there was some information published for limited circulation within the Soviet government in 1974, but even these sources only vaguely mention an "industrial accident" without any information on the date or location of the accident.

This wasn't the only nuclear disaster the Soviet Union covered up. In 1956, fallout from a nuclear weapons test at Semipalatinsk, Kazakhstan led to hundreds of people falling ill from radiation sickness, but New Scientist writes that Soviet officials promptly covered up any reports of the disaster.

Medvedev's revelation

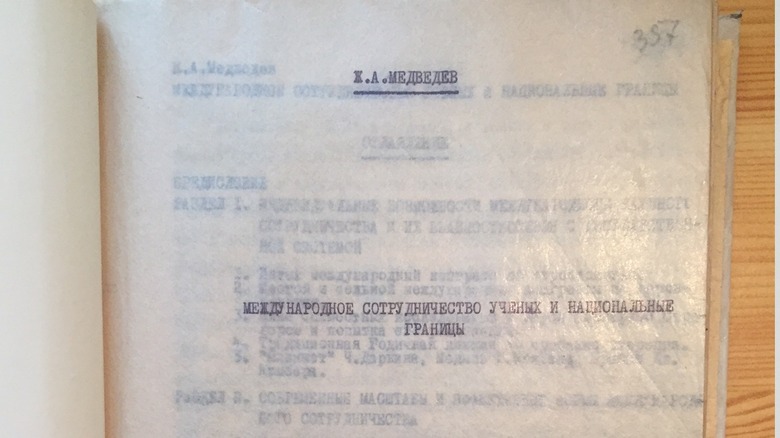

The international community didn't know about the Kyshtym disaster until almost 20 years after the disaster, when Soviet scientist and dissident Zhores Medvedev wrote about it for the New Scientist in 1976. In From Legacy to Heritage, Tatiana Kasperski writes that Medvedev himself didn't know exactly the full story of the Kyshtym disaster, but managed to put together bits of information from Soviet scientific publications about the effects of radiation on plants and animals, realizing that such information could only have been acquired as a result of a disastrous and unintended nuclear contamination.

According to "Nuclear Disasters & The Built Environment" by Philip Steadman and Simon Hodgkinson, Medvedev estimated "tens of thousands of people were affected, though the figure has never been made public. Probably hundreds died quickly, thousands more slowly." Medvedev's reports were corroborated by Professor Lev Tumerman, a radiobiologist and former head of the Biophysics Laboratory at the Institute of Molecular Biology in Moscow, who had visited Chelyabinsk and Sverdlovsk in 1960. In 1979, Medvedev also published the book "Nuclear Disaster in the Urals," detailing what he'd managed to discover about the accident.

TIME Magazine reports that a few years later, in 1979, researchers at the Oak Ridge National Laboratory in the United States "noticed that the names of about 30 small towns in the region had disappeared from Soviet maps." And according to New Scientist, the Oak Ridge team was the first group of nuclear experts to acknowledge that Medvedev was telling the truth.

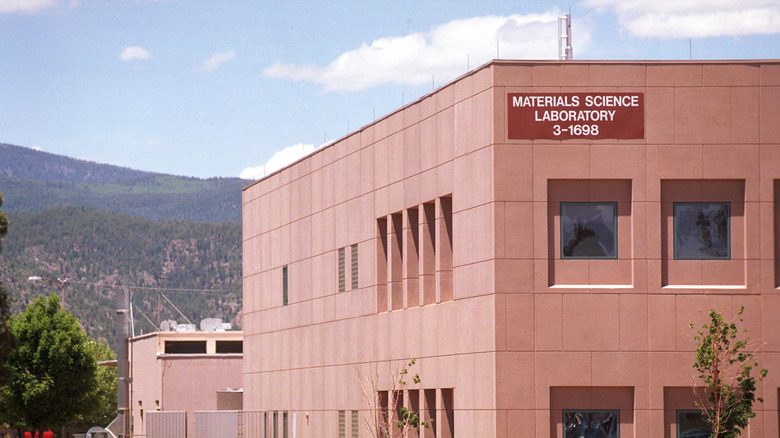

Western denial

Despite Medvedev and Tumerman's reports of the Kyshtym disaster, many in the West denied that any nuclear accident occurred in the Soviet Union. In a 1982 report released by the Los Alamos National Laboratory, the disaster is referred to as "the so-called Kyshtym Disaster." In this report, instead of acknowledging the evidence of the nuclear disaster, scientists at the Los Alamos National Laboratory attributed the reports of the Kyshtym disaster to "a series of relatively minor incidents, embellished by rumor, and severely compounded by a history of sloppy practices associated with the complex."

However, it's likely that the scientists at Los Alamos National Laboratory had an ulterior motive, which they subtly acknowledge with the line "the allegations surrounding it bear heavily on the whole question of nuclear waste disposal in the U.S." Considering that this report came out three years after the Church Rock uranium mill spill, the United States government had a vested interest in covering up the effects of nuclear waste spills.

Even the CIA had contradictory information about the Kyshtym disaster. According to New Scientist, CIA documents released in response to a Freedom of Information Act request claimed that there were two nuclear accidents in the Soviet Union, one in 1958 and one in 1960 or 1961. And one CIA document claimed that the accidents were caused "by a top-secret test in which the USSR allegedly exploded a 20-megaton device in the air over a mock village populated by goats and sheep."

An unknown death toll

Due to the cover-up and secrecy surrounding the Kyshtym disaster, the actual death toll of the disaster is unknown. According to the Associated Press, official statements maintained that there were no casualties whatsoever. But according to Mother Jones, officials later admitted that almost 1,000 people living near Chelyabinsk-40 were diagnosed with chronic radiation sickness, although the actual number is likely much higher. Until 1990, "local health officials were legally prohibited from acknowledging even the existence of radiation sickness, much less the fact that it has been killing people for the last 40 years." Instead, people were diagnosed with "ABC disease," which translated to "weakened vegetative syndrome."

Thousands of people also ended up with serious illnesses due to the radiation. In 1992, it was estimated that in the local population over the previous decade, diseases of the circulatory system increased by 31%, bronchial asthma increased by 43%, congenital anomalies by 23%, and gastrointestinal illnesses by 35%. In addition, the cancer rate in Chelyabinsk was the highest in the Soviet Union.

In "A Very Expensive Poison," Luke Harding writes that combined with the dumping of the toxic waste in the water, the contamination of the area had widespread effects more than 30 years after the Kyshtym disaster. Paula Chertok, a former resident of Chelyabinsk, recalled that everyone she knew from Chelyabinsk had some form of cancer or blood disorders. In some areas, villagers rarely live past the age of 50.

Soviet acknowledgement

It took over 30 years after the disaster for the Soviet Union to finally confirm that the Kyshtym disaster had occurred. New Scientist reports that in 1989, the Soviet Union finally acknowledged and released the first detailed account of the Kyshtym disaster. However, even this acknowledgment claimed that there were no deaths related to the immediate aftermath of the accident or in the succeeding decades.

After the Soviet acknowledgment, Medvedev was vindicated, having been met with accusations from British and American scientists that he was "a charlatan and a KGB agent, and was accused of trying to disrupt the U.S.'s nuclear program by creating panic."

The Washington Post reports that in 1990, the Soviet Union also acknowledged that millions of tons of toxic radioactive waste had been dumped into the Techa river. Unfortunately, these acknowledgments were too little too late. In towns like Muslyumovo, babies are often sick from the moment they're born and up to 80% of villagers are chronically sick. Gulfarida Galimova, a local doctor, states that "we have been so genetically harmed that our descendants will not be able to escape this curse ... Our cows eat radiated grass. The potatoes we grow in our back yards are poisoned. The only solution is to close this entire region off — and not let anyone come here for 3,000 years."

Still a closed city

In 1994, Chelyabinsk-40/65 was renamed Ozyorsk, also written Ozersk, but as of 2022, it remains a closed city in Russia. The Guardian reports that foreigners and non-resident Russians are prohibited from entering the city and need special permission from the Federal Security Service (FSB), Russia's security agency and successor to the KGB. Filming in the area is also prohibited. As of 2020, there are over 35 other closed cities in Russia.

People living in Ozyorsk are allowed to leave the city provided that they have a special pass as well. They can also leave the city for good if they so choose. But despite the fact that Ozyorsk is often called the "graveyard of the Earth" due to the immense radioactive contamination in the region, few of the city's 100,000 residents make the choice to leave.

Although the Mayak nuclear plant was mostly shut down and production at the reactors was halted by 1991, NTI writes that as of 2021, there remains one facility that is involved in fissile component production. After 1994, the United States worked with Russia to build the Fissile Material Storage Facility at Mayak, which is used to store plutonium and highly-enriched uranium from dismantled nuclear weapons. The facility started accepting materials in 2006.

Meanwhile, radiation warning signs remain by the Techna River, some of which were installed as recently as 2020. And some Ozyorsk residents claim that the dumping of toxic waste continued well into the 21st century.