Famous Events That Never Actually Happened

The ancient Greek writer Herodotus had two nicknames, "the father of history" and "the father of lies," and the people who called him by these names used them to mean the same thing. History as we receive it is often skewed by various biases and propagandistic impulses; it is, as the saying goes, written by the winners.

As it turns out, a lot of things you think you know about history are just flat-out wrong, and not just elements that have been exaggerated or downplayed; they just completely didn't happen at all. Some of the foundational stories of American and Western culture are complete fabrications meant to pass on some greater truth, or in some cases to achieve some more sinister purpose.

This list takes a look at events from across history that embody the message from Tim O'Brien's novel "The Things They Carried," that "a thing may happen and be a total lie; another thing may not happen and be truer than the truth."

Paul Revere's midnight ride

"Listen, my children, and you shall hear / Of the made-up ride of Paul Revere!" The legendary image of Paul Revere as a lone rider blasting through the Massachusetts countryside, warning American colonials that the British were coming, has its origins in an 1860 poem by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, which he wrote primarily to warn America that it was in danger of breaking apart.

Longfellow greatly rearranged and simplified much of the real historical narrative of the night of April 18, 1775. For one thing, Paul Revere didn't receive the famous "one if by land, two if by sea" lantern signals; he sent them. He wasn't a solo rider; he was just one part of a larger warning system that included Dr. Samuel Prescott, who actually warned the militia at Lexington and Concord after Revere was arrested outside Lexington. He didn't shout "The British are coming!" either. The one quote we have from him (via Smithsonian) was his reply to someone telling him he was making too much noise: "Noise! You'll have noise enough before long! The regulars are coming out!" Revere was important — and a hero — but his deeds have been much exaggerated.

So why did Longfellow turn Paul Revere into his solo hero? Perhaps because "Listen, my children, and you shall hear / Of the midnight ride of Samuel Prescott" doesn't rhyme.

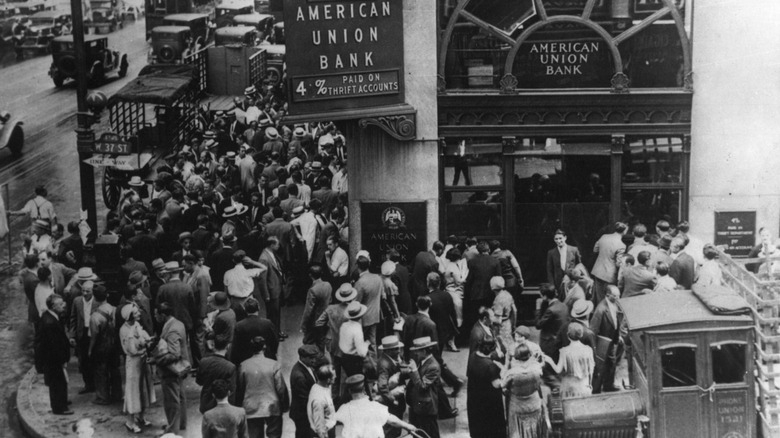

Stock traders jumping to their deaths after the 1929 market crash

On October 29, 1929, a day that would be known as Black Tuesday, the stock market crashed at an unprecedented rate, losing billions of dollars of value. This market collapse, together with increased unemployment and bank failures, led to what was then the longest and most significant economic downturn in history: the Great Depression.

One of the major causes of the market crash was the fact that a decade of speculation and many other confusing factors had inflated the market. Consequently, a lot of investors whose lives were tied up in bad investments suddenly found that not only was all their money gone, but they had also screwed up the world so bad that it would take the whole globe agreeing to defeat Adolf Hitler to get us out of it.

As such, the popular notion, even at the time of the Depression, was that stockbrokers on Wall Street died by suicide en masse by jumping out of buildings on the day of the crash, to the point that Will Rogers joked that you had to stand in line for a free window. The idea is popular enough to have inspired a bizarre arcade game in 1982, in which you catch investors falling from the sky. However, the rates of death by suicide did not actually spike during October 1929, and those investors who did generally didn't fall out of windows.

If you or someone you know is struggling or in crisis, help is available. Call or text 988 or chat 988lifeline.org

The exodus from Egypt

The story of the exodus is one of the central stories of Judaism, telling how the people of Israel were freed from slavery in Egypt by God, entering into a covenant with him, which ultimately led to their arrival in the promised land. The story is spread out over the books of Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy, four of the five books of the Torah, the central scriptures of the Jewish faith.

The story might be familiar to you, as it is foundational to much of Western culture. The Jewish people are enslaved in Egypt, Moses tells the Pharaoh, "let my people go," there are some plagues, they walk across the sea, they wander in the desert, and so on.

At any rate, while it might be easy to dismiss the more magical aspects of the story — such as sticks turning into snakes, angels of death, and waterbending — you might similarly conclude that, well, it's likely that the Jewish people were held in servitude in Egypt for a while (no, they did not build the pyramids) and then escaped or were let go and wandered around looking for a place to settle. However, there is no direct archaeological evidence that the Israelites were ever in Sinai, regardless of the emotional and spiritual truth that the story provides people.

George Washington and the cherry tree

If you know one thing about George Washington, it's probably that he was the first American president. If you know another, it might be that his face is on money and/or Mount Rushmore. A third thing might be that he had wooden teeth (which is false, by the way). If you're a big shot who can hold five facts in your head at one time, you might also know the story of the cherry tree.

As the story goes, a young George Washington was given a hatchet as a gift by his father. Then he went and took his ax and gave a cherry tree 30 whacks. When George's father discovered his son had chopped his cherry tree, the future president replied, "I cannot tell a lie. I did cut it with my hatchet."

However, none of that happened. The story was introduced in the fifth edition of a biography of Washington from 1806 by an author named Mason Locke Weems, who wanted to tie Washington's political success to a life of virtue. The book was a bestseller, and now the story is everywhere. The irony of crafting a dishonest story in order to impart the value of a life of honesty was apparently lost on Weems, who was probably too busy rolling around in dollar bills from his book sales to even think about it.

Christopher Columbus's discovery of America

Pretty much every school child in America learns on their first day of history class that America was discovered by the Italian explorer Christopher Columbus, who, in 1492, sailed the Niña, the Pinta, and the Santa Maria across the Atlantic Ocean in an attempt to reach Asia and subsequently prove that the world was round.

Except, almost none of that is true. For one thing, it had been well known since the time of ancient Greece that the Earth is round; Columbus did think it was smaller than it actually is, but only thanks to some bad math. He definitely didn't "discover" America: even setting aside the fact that there were thousands of people already living there, he wasn't even the first European to land in the Western Hemisphere, either. The Norse explorer Leif Erikson is believed to have landed and made a settlement in North America 500 years prior. Also, of course, Columbus never set foot on the soil of the North American mainland, but only Central America, South America, and various islands in the Caribbean.

Nero fiddling while Rome burned

An enormous fire hit the city of Rome during the early days of its empire, in A.D. 64. The fire burned for six days and consumed 70 percent of the city, leaving about half the people without homes. Popular legend states that the emperor Nero, who always fancied himself to be a great artist (to the extent that his dying words were allegedly, "Qualis artifex pereo," or "What an artist dies in me!") spent the time during the fire playing music and singing about Rome's destruction. This story gave rise to the popular expression, "Nero fiddled while Rome burned," which has gone on to describe anyone who acts ineffectually during a time of crisis.

The first part of the saying is easy enough to debunk: the fiddle did not exist until about a thousand years later. If Nero was playing anything at all, it would have been a cithara, an instrument similar to a lyre and the name of which is the source of our word "guitar." However, there's no evidence he was cithara-ing while Rome burned, either. The closest report comes from the Roman historian Tacitus, who says there were claims that Nero sang about the destruction of Troy during the fire, but even Tacitus found this story spurious.

Nonetheless, Nero was still kind of a jerk about the fire, even if he didn't fiddle during it. He blamed the whole thing on the still-obscure religious cult called Christians, and then built a big house for himself on the ruins.

Marie Antoinette's suggestion to 'let them eat cake'

Why did the angry peasant class of the French Revolution cut off the head of their queen, Marie-Antoinette? According to popular knowledge, it was because she said they should eat cake.

The story goes that someone told the queen that the people of France had no bread, to which she responded, "Qu'ils mangent de la brioche," or "let them eat cake." Well, no. That actually means "let them eat brioche," which frequent Food Network viewers will know is just a fancy, more expensive bread. The effect is the same, but you might be picturing it wrong. The joke is that it's exactly the kind of thing an out-of-touch, oblivious person would say, like complaining that young people crushed by debt aren't buying enough napkins. ("Millennials are killing the cake industry," says queen.)

There is no historical evidence that Marie Antoinette ever said any such thing. Indeed, variations of that story have existed around the world in multiple languages for centuries before Marie-Antoinette was even born. The first occurrence in print of the French-language "brioche" version was in a book by French philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau, who attributes the quote to an anonymous princess. Marie-Antoinette was a princess at the time, but too young for anyone to care about her bread opinions. Rousseau-inspired revolutionaries likely applied her name to the story as a form of propaganda.

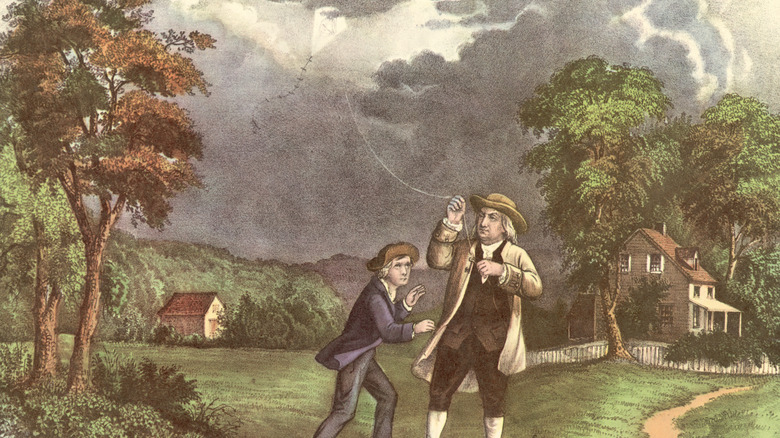

Ben Franklin's kite experiment

One of the best-known stories of America's founding fathers is that of inventor-statesman-diplomat-ladies' man Ben Franklin discovering electricity by flying a kite with a key tied to it in a storm. The kite is struck by lightning, Franklin touches the key, gets shocked, and probably says something like, "Wow, it turns out electricity exists!" There are, of course, more reasonable claims about this story, namely that he was simply proving that lightning was electrical in nature, and so on.

However, the experiment definitely didn't happen that way, if it even happened at all. Most likely, the kite business was just a thought experiment that Franklin devised to determine whether lightning was indeed electricity — the existence of which people already knew about — proposing the idea in a letter to a friend. When the letter was published in France, French scientist Thomas-Francois Dalibard performed an experiment with a lightning rod and proved Franklin's hypothesis to be correct.

Whether or not Franklin subsequently flew a kite in a lightning storm is a matter of some debate among historians. What is not up for debate, however, is the bit about him touching a charged key and getting a shock: Even a much less powerful charge than an actual lightning strike would have fried Old Ben to a crisp. That said, despite all the myths, it is true that Franklin is responsible for proving that lightning and electricity are the same phenomenon.

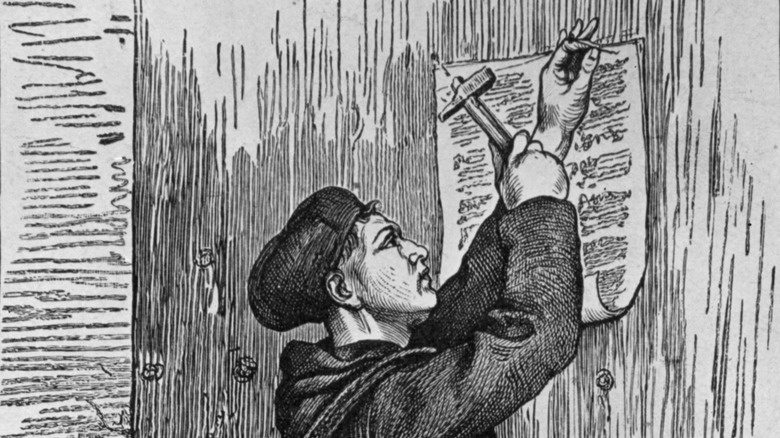

Martin Luther nailing his 95 theses to the church door

The story goes that on All Hallows' Eve in 1517, an obscure monk named Martin Luther from the small German town of Wittenburg strolled up to the Castle Church and hammered to the door a list of his soon-to-be-famous 95 theses, which laid out grievances with the Catholic church, primarily centered on the sale of indulgences (more or less the church exchanging forgiveness of sin for money). This bold act kicked off the Protestant Reformation and changed the world.

Is it real, though? Did this brassy monk stroll up to the church door, hammer in hand, and ring out revolution across the land? Well, the story was first written by someone who could not possibly have witnessed it, and first published after Luther died, having gone his whole life without mentioning this story to anyone. Additionally, Luther, who to his final breath considered himself a good and loyal Catholic, would not have done anything to so dramatically provoke his superiors in the church hierarchy.

So how did Martin Luther actually deliver his 95 theses to church leaders, asking them to cease the sale of indulgences? Well, most likely though a letter with the theses attached. But the image of a man nailing his complaints to the door of a church is so striking that it won't likely be replaced by a man mailing a letter.

The Gulf of Tonkin incident

Not all fake historical events are said to have happened in the distant past. There are major, world-shaking events reported in living memory that completely, actually, weirdly didn't happen. One such occurrence was the Gulf of Tonkin incident, a confrontation between ships in the Gulf of Tonkin near North Vietnam that led to the U.S. becoming more directly involved in the Vietnam War.

According to reports, on two separate occasions, an American destroyer was pursued and attacked by North Vietnamese torpedo boats in 1964. The result of these reports was the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, which authorized President Johnson to more or less go buck-wild on Vietnam, which, as you know, turned out just super, super well. (It did not.)

It turns out that we were all punked. Declassified documents have revealed that in the initial encounter, the U.S. ship fired the first shots as a warning but never reported it, making the Vietnamese look more like aggressors. The second incident never even happened at all. Instead, U.S. ships motored around in a storm shooting torpedoes at tall waves, which could look like ships on radar, for hours. It was initially reported as an attack to the higher-ups, but when they realized the mistake, they decided to go with it anyway.

Lady Godiva's naked ride

A well-known story details how Lady Godiva, the wife of Leofric, the lord of Coventry, England, felt sympathy for the exorbitant tax burden placed on the peasantry of the medieval town. Leofric tells his pleading wife that he will lower taxes when she rides naked through the town, which she does. In a side element to that tale, out of respect, all of the villagers stay indoors while she rides, except for one randy boy named Tom who decided to take a look, getting struck blind and inspiring the phrase "peeping Tom" at the same time. Well, actually, most of it is probably wrong.

The story is based on a real person, a woman named Godifu (the Anglo-Saxon name that the Latin "Godiva" comes from) who was the wife of Leofric, the real count of Coventry. But historians of the time did not indicate there was anything notable about this woman outside of being married to an important man, and naked horse riding didn't garner a mention. It wasn't until two centuries later that monks started recording this legend, likely as a way of explaining certain historical acts of generosity on the part of Leofric. This later spread even more via poems and artists looking for classy reasons (like history) to paint naked ladies.

Romulus founded Rome

The story of Rome's founding is familiar to most: The city is named after Romulus, who had a twin brother, Remus, whom he killed after Remus jumped over the still-in-progress walls of Rome because Romulus didn't like the metaphorical precedent his brother was setting. The two were supposedly already at loggerheads over who had seen the more important birds, and were raised by a wolf who nursed them as babies. Their father was the god Mars, and Romulus himself became the god Quirinus after he disappeared in a magical whirlwind to save himself from the murderous jealousy of Roman senators.

But were Romulus and Remus actually real? The legendary account of Rome's foundation in 753 B.C. appears to be just that; a fantastical legend. Romulus was almost certainly a mythical figure, whose name was likely a back-formation from the name Rome, not vice versa. Despite some fringe beliefs that excavations uncovered signs of Roman settlement in the eighth century B.C. (including a cave under the Palatine Hill that tradition says is where Romulus and Remus gobbled up wolf milk), the overwhelming scholarly consensus is that the presence of a wall does not prove that Rome's most famous wolf boys were a real thing.

Julius Caesar's last words were 'Et tu, Brute?'

All things considered, Shakespeare's famous play "Julius Caesar" is actually a pretty decently accurate depiction of the events leading up to and following the assassination of the last great leader of Republican Rome.

Shakespeare used ancient historians Plutarch and Suetonius as his primary sources for the broad strokes and just kind of jazzed their version of events up a bit. There are definitely inaccuracies propagated by the play, however: The soothsayer (who was real) didn't say "beware the Ides of March," for example, and Shakespeare (like Plutarch before him) really undersells the importance of Decimus. But one notable dramatic change that Shakespeare makes comes with what is arguably the play's most iconic line, which in a play full of iconic lines such as "Friends, Romans, countrymen, lend me your ears" is really saying something.

In Shakespeare's version of events, the dying Caesar stops fighting his attackers when he sees his friend Brutus among his killers, gasping out, "Et tu, Brute?" which has become the go-to interjection for those suffering betrayal. According to the Roman historian Suetonius, some bystanders said Caesar intoned the Greek "Kai su, teknon? (You too, my child?)" but Suetonius and Plutarch both agree that history's most famous soldier was probably too busy fighting back to actually chime in with history's most famous dying words.

Archimedes' eureka moment

According to legend, the tyrant Hiero suspected that a golden crown he commissioned might not be pure gold due to the machinations of a greedy goldsmith, so he commanded a local mathematician to prove the crown had been laced with silver. That mathematician, Archimedes, was pondering the problem when he sat down in the bath. The water rising around him caused him to realize that he could measure volume with water displacement, and then he ran naked through the streets of Syracuse shouting "Eureka!" or "I've found it!"

This story has led to the word "eureka" being a common expression for discovery and epiphany; it's even the state motto of California, thanks to its long association with the gold rush. There is, of course, just one problem: Archimedes never said this. Well, he probably said the words "I found it" at some point in his life. He just didn't do it in what was likely history's only math-inspired streaking session. There is no record of this story until it's told by Archimedes fanboy Vitruvius, almost 200 years after it is supposed to have happened. Even for Galileo, this story didn't pass the smell test, as he knew a scientist like Archimedes would have had more accurate ways of making such a measurement.

A falling apple led Isaac Newton to the theory of gravity

The image is an indelible one, indeed one of the best known in science history: A young Isaac Newton sits under an apple tree when suddenly an apple drops on his head, and presumably as soon as he stops hollering at the tree, he has discovered gravity, thereby ensuring his place in history. But while the image of an apple wanging Isaac Newton on his bewigged head has come to be considered the quintessence of the "aha!" moment, things didn't happen exactly that way.

Newton was forced to leave Cambridge University in 1665 thanks to a little bit of plague going around. He returned to his childhood home of Woolsthorpe Manor and, while wandering through its orchard, saw an apple fall from a tree and drop to the ground. This caused him to ponder why an apple, as well as other things like cats and pumpkins and buckets of sand, always fall down and not up or sideways or whatever. This led him to develop his theory of universal gravitation, and fame awaited. Did he discover gravity because of a falling apple? Yes. Did it bonk his bean? No.

Catherine the Great died from intimate horseplay

Catherine the Great was a German princess who gained control of Russia by staging a coup against her own maniacal husband and making herself empress. From there, she not only enriched Russia by building schools, writing laws, and winning wars, she also protected her vast country from invasion and annexation by more powerful European neighbors, such that Russia prospered to a degree unmatched by most rulers before or since. Catherine the Great was, in short, pretty boss.

And yet the only thing you probably "know" about her is that she died trying to do the nasty with a horse. Accusations that Catherine's insatiable sexual appetite was at the heart of her political success were incredibly common during her time, attempting to undercut her political ability as a woman by showing her to be some ungodly freak of nature. Such tales only grew upon her death, with the intent being to show that her, ahem, unbridled desire for sex had ultimately led to her own destruction, crushed when a horse fell out of a sex swing.

The truth is, Catherine the Great died of natural causes, alone and with no horses in the vicinity. On November 5, 1796, she drank some coffee and sat down to write. Three hours later, she was found on the floor, having suffered a cerebral hemorrhage.

Mama Cass died from choking on a ham sandwich

"Mama" Cass Elliot was a singer and actress probably best known for being a member of The Mamas & the Papas, a Rock and Roll Hall of Fame group best known for the songs "California Dreamin'" and "Monday, Monday." Following that group's breakup, Mama Cass would release five solo albums and make numerous TV appearances.

Sadly, Mama Cass passed away on July 29, 1974, at the tragically young age of 33. Following her death, there was no shortage of increasingly buckwild theories surrounding the circumstances: that she died of a drug overdose, that the FBI assassinated her, that she was pregnant with John Lennon's baby, and so on. But no rumor has plagued the public consciousness more than the idea that Mama Cass died from choking on a ham sandwich. This story has its origins in a hasty, inaccurate assessment by the first doctor on the scene. In fact, Elliot had no food in her windpipe (and no drugs in her system) and had died from a heart attack.

Mussolini made the trains run on time

Benito Mussolini was a brutal, Machiavellian dictator: his fascist regime had no underlying philosophy other than to use violence, deception, and terror to subjugate the people of Italy under the heel of its nationalist leader. But hey, at least he made the trains run on time. Or did he?

No, he didn't. "Fascist efficiency" was a myth propagated by Mussolini and his followers to engender the support of the people so he could, of course, shore up more power. The notion that Mussolini's policies were responsible for Italian trains being reliable and punctual was a rumor spread by the fascists, done to convince people that fascism was a system that was good for them and benefited them in concrete, everyday ways.

The fact of the matter is that while the Italian rail system had in fact fallen into disrepair during World War I, most of the repairs and improvements that happened were done in the 1920s before Mussolini rose to power, though he was happy to take credit for them. That said, the trains didn't even run on time despite these non-Mussolini repairs. People who lived in Italy at the time have widely attested to the fact that Mussolini's far-famed railway punctuality was a bunch of bologna.

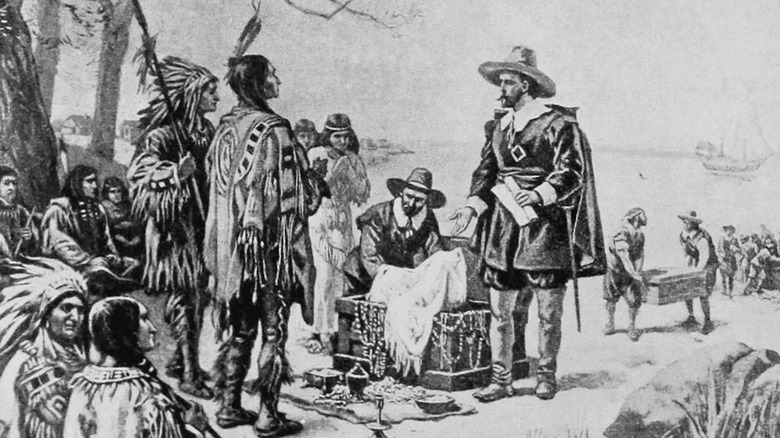

Dutch colonists bought Manhattan from Indigenous Americans for a few beads

These days, real estate in Manhattan generally goes for thousands of dollars per square foot, but one of the most commonly repeated stories from America's colonial history says local Native American tribes sold the whole shebang to Dutch colonists for a mere $24. And not even $24 cash; it was supposedly an equivalent value in beads. The story is meant to illustrate what a historically bad deal the Native Americans got, getting some trinkets in exchange for what is now some of the most valuable real estate in the world.

The truth is a lot more complicated. For one thing, that $24 figure has not been adjusted for inflation since historians first reported it in the 19th century, and would be roughly worth $1,000. Still not a fair price by any stretch, but not quite as low as the story goes. Additionally, the original deed of sale has been lost, so we don't know exactly what goods were traded, but the deed from the sale of Staten Island might give us an idea: clothing, gunpowder, kettles, lead, axes, knives, and other tools that would have certainly been more useful than beads. Lastly, the Indigenous people most likely saw this sale as giving usage rights to the Dutch, not relinquishing the land wholesale. Unfortunately, even this modestly better bargain didn't work out great for them, either.

Albert Einstein was bad at math when he was a child

If you ever failed a test at school, especially a math test, there's a chance some adult told you to cheer up because even Albert Einstein failed math as a kid. The lesson, supposedly, is that even though you don't know the difference between a trapezoid and a rhombus now, one day you could have literally some of the most important ideas of all time and revolutionize physics forever. Maybe, in fact, your inability to do long division is a good sign?

We hate to be the bearer of bad news, but it seems that young Einstein's legendarily poor elementary school performance has been somewhat overblown. He actually got very good grades in school, though he bristled at their rote methods of teaching. He was studying college physics texts by age 11, and at 13 he was talking up how much he loved Immanuel Kant. Unless you can boast the same, your F in math might just literally mean you're bad at math.

That doesn't mean Einstein didn't ever fail at anything, though. He failed the entrance exam to Zurich Polytechnic the first time he took it, when he was still 16 and almost two years away from graduating high school. But it turns out the reason he failed was because the exam was in French, a language he had barely studied. But while he had trouble with the language and biology sections, there was one part he still aced: mathematics.

Ferdinand Magellan was the first person to circumnavigate the globe

Who was the first person to sail all the way around the world? Chances are good you said Ferdinand Magellan. In less-than-accurate history lessons and trivia flashcards, Magellan is the guy who tends to get credit for being the first person to circumnavigate the globe.

But Magellan was really just the almost-the-first person to circumnavigate the globe. While Magellan set out in 1519 and managed to lead his crew across the Atlantic, through South America, and over most of the Pacific Ocean, he was killed by Indigenous people in the Philippines during a scuffle. So while it's true that his ship made it back to Spain in 1522, Magellan was not there to cross the finish line. In fact, only 18 of Magellan's original crew of 260 men made it back home. It's probably better to give the credit to Juan Sebastian Elcano, who took over command after Magellan's death, though some experts argue for Magellan's Malay slave Enrique, who may have completed the journey in a piecemeal fashion before any European.

Lupe Velez drowned in the toilet

Like many performers, Mexican-born actress Lupe Velez deliberately cultivated a larger-than-life reputation, so it's not easy to tell where the act ends and the real Velez begins. She occupied an uncomfortable place in Hollywood, benefiting from her perceived exoticism while also being dismissed and mocked as a racial caricature. Her dramatic personal life overshadowed Velez's talent, with tumultuous relationships with Johnny Weissmuller, the original Tarzan, and Gary Cooper, a popular actor in Westerns, delighting fans of Hollywood gossip. She was ultimately replaced as "Hollywood's Favorite Mexican" by the easier-to-handle Dolores Del Rio.

But whatever else you want to say about Lupe Velez, she didn't drown in the toilet — or anywhere else. She was found dead in her bed, having died by suicide at the age of 36, leaving behind notes that thanked, among others, the American press. The toilet myth seems to date from "Hollywood Babylon," a 1965 compilation of salacious stories and crime scene photos by Kenneth Anger. Whether this was a rumor Anger heard and decided to include without checking (or despite knowing it was false) or whether he simply made it up himself is unknown.

If you or someone you know is struggling or in crisis, help is available. Call or text 988 or chat 988lifeline.org

Messalina threw a competitive orgy

As the surviving sources would have it, the Roman Empress Messalina, wife of the emperor Claudius, was one of the most sexually motivated women whose exploits have been recorded. At night, she would slip out of the palace, paint her nipples gold (it is not recorded with what), and work in a cheap bordello simply to satisfy her enormous lust. The story even says that Messalina, who worked under the name of "the She-Wolf," held a competition with a well-known lady of the evening to see who could entertain more men in a single day — and won. Naturally, when the emperor and his government found out, they killed her and chiseled her name off as many monuments as they could find.

If it sounds too titillating to be true, that's because it probably is. Like many among the Roman elite, Messalina was probably jockeying for power and influence, and history has many examples of attractive young women using sex to advance their own position in similar contexts. She might even have committed adultery because she found someone she liked better than emperor Claudius, who was probably 20 years older than she and not, by that day's standards, a handsome man. But the stories of the sex work and the contest are more likely to be exaggerations, perhaps partly hoping to discredit her widower by showing he couldn't even control his own spouse.

Romans salt the earth after the fall of Carthage

We've all hated some institution enough that we wanted to burn it down and ensure it could never come back, be it a high school, an insurance company, or just a terrible employer. So it's perhaps tempting to understand the Romans who, having finally defeated their arch-rival Carthage, salted the earth around the city so nothing would ever grow there again, rendering desolate the home base of their old enemy.

Well, they didn't do that because it would have been stupid. In the different climate of antiquity, the area around Carthage (now northern Tunisia) was wonderfully productive and right next to the magnificent harbor that had allowed Carthaginian ships to prowl the Mediterranean. Africa, a term that referred to a single province before the meaning expanded to cover the whole continent, fed most of the city of Rome during the height of the empire. Rome's real revenge on Carthage wasn't the salting of the earth; it was the filling of their bellies with African food shipped out of the rebuilt, Romanized new Carthage.

The idea of the salted earth seems to have been inspired by the practices of people further east, who would ritually sprinkle salt over a defeated city. The evocative image spread through 19th-century texts that quoted each other, and a legend was born.

The Russians let winter defeat Napoleon for them

Napoleon's disastrous invasion of Russia in 1812 is often remembered as the time France went to war against winter. Sure, the Russians retreated and stripped the land of supplies on their way out, forcing the French to proceed with fewer and fewer provisions, but the star of the show was Russia's famously inhospitable climate. At least, that's how the story goes.

There's truth in this interpretation, but it oversimplifies the Russian war strategy and omits two climactic battles of the Napoleonic Wars. About 75 miles outside Moscow, the Russian general Kutuzov stopped his retreat and turned to meet Napoleon in battle near a village called Borodino. Over a quarter of a million men fought, and while the Russians were forced to retreat, they had badly wounded the French force. The French could not meaningfully reinforce themselves deep in Russian territory, but Kutuzov's army could.

After the French took Moscow, hung out for a while, and decided to leave, they hoped to depart Russia through a warmer route to the south that had not just had two armies strip it bare, but Kutuzov had planned for this. In a bloody battle at a town called Maloyaroslavets, Kutuzov denied the French army access to the southern road, forcing them into a chilly, limping, and devastating retreat through the ruined path they had already taken, harassed by irregular forces the whole way. Winter may have beaten the Grande Armée, but the Russians held it down for the killing blow.

The Donation of Constantine

From the eighth century until 1871, the pope was not only the spiritual leader of the world's Catholics (for good or ill) but also a major political ruler. The papacy came with the lordship of the Papal States, a meaty chunk of central Italy subject to the pope's rule. That situation first came about through a complex bit of horse trading that involved the pope crowning Pepin, a usurper who had taken the French throne, and being rewarded with lands that the new king then conquered.

As a legal fig leaf, the pope's rule over the Papal States was justified by the Donation of Constantine, a document proving that the first Christian emperor of Rome had intended the head of the church to rule in the physical realm as well. Furthermore, the Donation of Constantine argued that the pope enjoyed supremacy over other earthly rulers, including the power to raise or dethrone kings.

The Donation of Constantine was a forgery (amusingly Pepin, the initial target of the scam, couldn't read the document). Some people began to be suspicious as early as around 1000 CE, but in the 1440s, a scholar named Lorenzo Valla proclaimed that the bad Latin, plagiarism, anachronisms, and other flaws in the Donation of Constantine meant it was undoubtedly a forgery. This work seriously undermined the church's credibility on the issue, so of course they banned it, only formally acknowledging the millennium-old fraud in 1929.

Rome yeets Britain from the Empire

By the early 400s, it was clear that the Roman Empire wasn't doing all that well. Barbarians were invading, emperors were cycling through at a rapid clip, and provinces were occasionally setting up their own governments. In the context of this crisis, the emperor Honorius made a fateful triage decision: the prosperous but distant province of Britannia couldn't be defended anymore, so it wouldn't be. That departure of the Roman Army has intermittently loomed large in Britain's conception of itself, with a wistful Roman helmet often appearing on later personifications of the island.

But would an emperor really just yeet a province? Probably not. The fifth century is a confusing period in Western European history, and so the main source for this abandonment of Britain is a summary of a single set of imperial instructions sent by Honorius. Two other interpretations of the text offer different explanations. In one, "Britain" is a mistranscription for an Italian city name, maybe "Bruttium," which may make sense given that much of the document is about defenses of Italian cities. Alternatively, the fateful phrase "the cities of Britain must look to their own defense" may imply a continuation like "until I get rid of the foreign army that is right this minute rampaging in Italy."

But whatever Honorius meant, the result was the same. Britain may not have been unceremoniously chucked out the window of the Empire, but the central Roman government never recovered enough to reestablish control over the island province.

Margaret Pole's executioner chased her with an axe

It's a horrible image: a once-grand old woman, of some of the most respected blood of England, running for her life as blood streams down her body. Margaret Pole, Countess of Salisbury, had been sentenced to death for treason on trumped-up charges largely to punish her son, who was criticising Henry VIII's religious reforms. When the first blow of the axe failed to kill her, the countess hopped up and bolted, forcing the incompetent axeman to run her down.

Eyewitness accounts differ, but the version of the 37-year-old Lady Salisbury hopping up and running in a long skirt is likely an exaggeration of an already grim story. After having just been hit with an axe, she was probably not physically capable of such a feat. Additionally, as painful as the botched execution must have been, Lady Salisbury would have been aware of her own dignity. After all, Katherine Howard, Henry's fifth wife and a scared teenager when she went to her death, managed to die well, so this devout old noblewoman could have, too.

That said, it does seem to have taken eleven whacks to fully decapitate Lady Salisbury. Incompetent beheadings were a Tudor classic: the rebel Earl of Essex required three blows, and Mary, Queen of Scots took two, with her neck apparently requiring a last little sawing-through of flesh. It was a terrible end, but Lady Salisbury almost certainly held still for it.

Caligula made his horse a senator

Caligula, the famously deranged Roman emperor, was so daffy he made his horse a senator of Rome. Why not? It's a delightful story of royal madness and Roman decadence, and it's been kicked around so long that it feels true, even if not everyone who's heard the story remembers which emperor supposedly did it.

Pedantry first: the horse, Incitatus, was not to be made a senator but a consul, a different yet more powerful and prestigious office. Second, even the surviving sources that are not friendly to Caligula say that he only planned or threatened to elevate his beloved horse to the highest levels of government. Third, Caligula was probably kidding, zinging the Senate by proposing the horse as more competent than anyone in the current Roman government.

The horse may not have gotten to help manage the empire, but it did reportedly get plenty of special treatment. It enjoyed its own luxurious quarters, guards, and enslaved staff: all the comforts it might want with none of the responsibility of governance.

Edward II died from having a hot poker thrust into his business

It makes you sit up straighter just thinking about it. According to the most commonly repeated story, Edward II of England, having been deposed by his own wife, was assassinated by having a red-hot poker inserted into his rectum. This murder both removed the ex-king from the chessboard and ritually punished him for his homosexuality, with the added, humiliating bonus of making him notorious for his death centuries later.

The hot poker story doesn't occur in the first accounts of Edward's death, which present him dying either of grief or of a more mundane murder along the lines of suffocation. The poker shows up more than 10 years later and is usually hot, but not in every version. The logistics of such a death are also challenging, needing considerable physical effort by at least two men to hold the healthy middle-aged king, and a third to deliver the fatal insertion.

A minority view holds that Edward wasn't murdered at all, but hidden away and reported dead. Given that his son was the new king, the government ruling in the teenage Edward III's name might not have liked the idea of killing the king's father, even if he was incompetent, gay, and a threat to their position. We can never know for sure how or even if Edward died in 1327, but we can be fairly sure he didn't end up a toasted marshmallow.

King Harold was shot in the eye at the Battle of Hastings

With a mighty thwack, Anglo-Saxon England came to an end. The thwack, of course, was an arrow hitting King Harold's in the eye during the Battle of Hastings and clearing the English throne for the authoritative French buttocks of William the Conqueror. England — and the English language — would become more French in the coming generations, a process assisted by one of the most literal bulls-eyes in European history.

Probably not, though. The most contemporary accounts of Harold's death are either vague or describe him being hacked to pieces by several Norman fighters. It's a gory end, but it lacks the almost magical precision of an arrow going right through the eye. The lucky shot only appears later (and in some less reliable sources). As for its famous inclusion on the Bayeux Tapestry, the embroidered comic-strip history of the Norman Invasion, that comes from a later repair. Most of the arrows elsewhere on the cloth are short, medieval-style ones, but the one sticking out of the royal face is too long, matching the handful of other arrows added by well-meaning but misinformed conservators. This was probably originally a spear brandished by the figure, who may not even be intended to represent the unlucky Harold.

Genghis Khan fathered a substantial fraction of people alive today

In fairness, file this one under "not proven." A 2003 study published in the American Journal of Human Genetics showed that someone who lived in or near Mongolia roughly 1,000 years ago is the ancestor of one in every 200 people alive today, and an even-more-impressive eight percent of people with ancestry originating within the vast bounds of the Mongol Empire at its zenith. Circumstantial evidence points to Genghis Khan as living at more or less the right time and having the social and military power to, putting it bluntly, impregnate many, many women. The resulting sons were often also wealthy, powerful, and violent, and so the telltale gene spread and spread and spread.

It's a good case, but the information we'd need to prove it conclusively simply doesn't exist, as we don't have a genetic sample directly connected to Genghis Khan. Sure, he's the most likely candidate, but without a scrap of the khan himself, we can't rule out the scenario of a handsome, promiscuous, fertile man in his entourage being the originator of the huge lineage. And Genghis-or-whoever isn't the only mysterious patriarch in history: further studies have identified 10 more massive male-line groups of related people descending from a common ancestor.

Grand Duchess Anastasia survived the execution of the Romanov family

The idea of Grand Duchess Anastasia escaping the slaying of the rest of her family by the emerging Soviet state is attractive for obvious reasons: a thrilling escape, lost Romanov jewels, a beautiful, grieving princess, and perhaps best of all, one fewer dead child in a Europe that was just getting started on a miserable century.

The bodies of the tsar, his wife, their five children, and a few devoted servants were quietly disposed of after the murders, so it was easy for people to convince themselves that at least one of them might have escaped. Sometimes the myth even requires the valuables hidden in Anastasia's clothes to protect her from the hail of bullets. Real-life impostors and sentimental films kept the idea of Anastasia's survival alive in the public consciousness, and people hoped the little princess had made it.

She didn't. The bodies of the royal family were found in the 1970s, and there weren't immediately enough of them to account for all four grand duchesses, sparking a burst of hope for Anastasia-philes. Alas, in 2007, two more sets of remains were uncovered. Even though the corpses of the young women cannot be definitively identified within the family, there are enough of them to show that Anastasia did not outlive the remainder of her family.