Why Some People Don't Need Oxygen Tanks When Climbing Mountains

Climbing high mountains is one of the world's most dangerous sports. Alex Lowe, once hailed by The Guardian as the "world's greatest climber," was swept to his death by an avalanche. Hermann Buhl simply disappeared in a snowstorm on Nanga Parbat, per Summit Post; his climbing partners stood waiting for him in the whiteout, expecting him to be just a few yards behind. But the greatest danger comes from altitude. Higher than about 8,200 feet, as NPR explains, oxygen becomes more and more scarce. The first and mildest symptoms of altitude sickness include headache, loss of appetite, and poor sleep. Even before the 23,000-foot "death zone," as the air gets thinner, it can cause delirium and hallucination, as well as edema, or dangerous buildups of fluid in the lungs and brain.

Günther Messner, brother of the legendary Italian alpinist Reinhold Messner, died exactly like that in 1970. Delirious and lightheaded, as Vanity Fair recounts, Günther had just enough of his wits about him to know he couldn't descend from the peak of Nanga Parbat. His frostbitten, hallucinating brother went ahead of him, but Günther stayed put. It was the last anyone saw of him. Thirty years later, someone would find his femur in the snow.

Going up without a tank

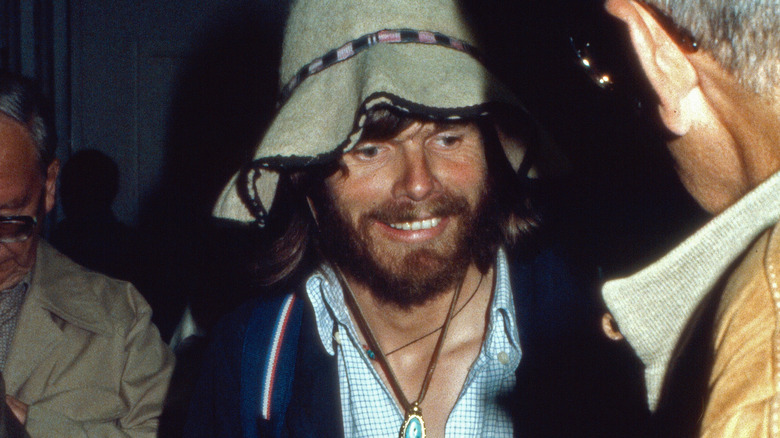

Deaths like Günther Messner's are the reason most serious alpinists carry tanks of supplemental oxygen on expeditions in the "death zone," or even below it. However, for various reasons — often mysterious — some climbers don't seem to need it. Reinhold Messner himself (above) was the first climber to eschew supplemental oxygen in the Himalayas. The craggy Tyrolean (later a member of the European Parliament for the Greens) has climbed Everest alone, with nothing more than a backpack and crampons, per Adventure Journal. As his Vanity Fair profile makes clear, Messner sees oxygen almost as a sacrilege, an insult to the spirit of nature.

But how does he do it? Medical tests show Messner to be unremarkable, as Outside points out, with no great VO2Max or other physiological markers of gifted athletes. A 1986 study of six world class climbers, Messner included (per The Guardian), found them all unremarkable. They had smaller muscles than the average distance runner; they were 40% less powerful than the average high jumper; and their lung capacity was the same as a sedentary control group's. Was Messner's ability to climb without oxygen just a matter of willpower?

The Sherpa

It may be true that Reinhold Messner can will himself past normal human limits, but there is more and more evidence that some humans have evolved to function well at high altitudes. NPR cites a study to that effect on the Sherpa people of the Himalayas. The Sherpa are an ethnic group, many but not all of whom live far higher than most human populations. Their work as porters, guiding alpinists on climbs and carrying supplies, is so famous that "sherpa" has become a synonym for mountain porter, or for anyone with unbelievable stamina.

According to the study, the Sherpa have a number of unique physiological traits. At high altitudes, people begin producing more red blood cells, which ferry oxygen to tissues around the body; this buildup thickens the blood, putting extra stress on the already overworked heart muscles. In Sherpas, however, this effect is greatly diminished. Sherpa muscles can produce more force anaerobically than other populations', meaning they need slightly less oxygen to exert themselves. And whereas most people's mitochondria, the tiny organs that produce oxygen at the level of the cell, become frail and "leaky" at high altitudes, Sherpa mitochondria are much more robust and efficient. NPR compares the overall effect to good mileage in a car, except the fuel in this case is oxygen, not gasoline. Sherpas get more "miles per gallon."

Practice and will

But that doesn't mean willpower doesn't make a difference. Another NPR article cited another study of the Sherpa, this time looking into their legendary strength. Sherpa porters, like the one shown above, have been known to carry packs heavier than their body in the thin air and cold of the mountains, up and down the world's steepest and most treacherous terrain. Are Sherpas just stronger than everyone else? Are their muscles bigger? Do they expend fewer calories through muscular contraction than other people?

In fact, there's nothing unusual about them physically, except maybe a tendency toward sturdy, compact frames. They expend as many calories as anyone else, and there's nothing special about their muscles. "They haven't got any trick," said one of the researchers.

The secret is probably practice. Sherpas who live in the highlands are already accustomed to negotiating steep roads; those who work as porters start at a young age, carrying loads day in and day out for years. Bodies adapt to this kind of stimulus. It's why practicing a lift with a heavy barbell gets easier the longer you work at it — or why playing a musical instrument, or speaking a new language, gets easier with time. Practice makes perfect.

The other side of the world

The Sherpas' physiological fitness for high elevations was an evolutionary adaptation. Their ancestors moved to the mountains; it took thousands of years for them to change.

Other mountain dwellers, in fact, show similar traits. National Geographic writes that the indigenous people of the Andean highlands, in South American countries like Ecuador and Peru, have also adapted to high thin air. They have — like whales — an unusually high hemoglobin count, meaning they can make better use of the oxygen they breathe than lowlanders can. They do not, however, exhibit a trait long observed among the Sherpa and other Tibetan highlanders, that of taking more breaths per minute than ordinary people. Tibetans also synthesize a remarkable amount of nitric oxide gas when they breathe, which dilates blood vessels and keeps blood flowing normally. These are two separate mechanisms, a researcher told National Geographic, hematological and respiratory, developed by different populations under different circumstances. But two mechanisms produce the same result: more efficient use of oxygen.

Training for lowlanders

Can climbers or athletes take advantage of these physiological techniques to help their performance, or must they rely on willpower, like Reinhold Messner? It depends. Many of the adaptations seen in Sherpas and Peruvian Indians took thousands of years to develop. If your ancestors came from Belgium, or Ghana, you can forget about extra hemoglobin and more breaths per minute.

However, as the BBC explains, altitude training is an old concept in sport. Besides the lore of boxers going to mountain camps to train for a fight, many elite athletes have tried to reproduce the thin air of high mountains in their training, specifically to cause temporary adaptations like a higher red blood cell count. The theory goes that a footballer or a runner who has trained herself to get by on low oxygen will experience a kind of "turbo boost" on the day of the match or the race. However, the BBC notes that this process can take weeks, and does not necessarily deliver results.

Another, cheekier method might be smoking tobacco. The infamous "therapeutic cigarette" can help climbers regulate their rate of breathing, as the British Medical Journal notes, and as Go Extreme Sports speculates, heavy cigarette smokers are already "trained" on low-oxygen routines. It's a well-tried method. As the Daily Mail reports, Joe Brown smoked 2,000 cigarettes on his 1955 ascent of Kangchenjunga; there were 25,000 of them, plus 16 pounds of pipe tobacco, in his baggage, for him and his Sherpa porters.