14 Popular Products That Came From Military Research

Since time immemorial, humans have been researching new and innovative ways to destroy one another. While this is generally a bad thing, military research and innovation have had the positive side benefit of providing us with certain products that have improved our standard of living. Consider, for example, the internet. Life without the internet these days is unthinkable — in fact, you couldn't even read this article without it. As Britannica maintains, you can thank the military for this. The first networks that developed into today's internet were developed by the U.S. Department of Defense in the 1950s and 1960s. The major breakthrough occurred in 1969 with the development of ARPANET, which is considered the first general network for computers.

There are many other products that stem from military and defense research that, at first blush, you wouldn't think have anything to do with defense. But as we shall see, military research is a big thing. In 2022 alone, the Department of Defense requested a research budget of $112 billion — the largest ever. Let's take a look at some of the products military research has given us, from the quirky to the mundane to the useful.

Duct Tape

One of the most versatile inventions ever to come from military research, and one that keeps the world bound together, is duct tape. Judith Sumner's 2019 book "Plants Go to War" relates the story of how Vesta Stoudt, an Illinois woman who worked in a munitions factory during World War II, had heard that the troops had difficulty opening boxes of cartridges while in the heat of battle. Apparently, the paper often ripped and soldiers had to use knives to slice open the wax seal. She thought if an adhesive tape made from waterproof cloth was used to seal the boxes, they would be easier to open, perhaps saving lives.

With this in mind, Stoudt wrote to President Franklin Roosevelt about her idea. The president promptly forwarded her letter to the War Production Board. The agency turned to Johnson & Johnson, which developed the waterproof tape using a type of canvas called cotton duck, hence the product's original name: "duck tape." (One brand still uses that name today.) Duct tape has been adapted for innumerable uses since then, but even soldiers during the war recognized its value. Johnson & Johnson quoted their corporate historian Margaret Gurowitz as saying, "The military called the waterproof, cloth-backed, green tape 100-mile-per-hour tape because they could use it to fix anything, from fenders on jeeps to boots."

Sanitary napkins

One vital product that curiously derived from the military is women's sanitary napkins for menstruation. Smithsonian explains that until the early 20th century, most women had to rely on homemade sanitary products. There were some exceptions for sale such as Lister's Towels, but these were expensive and not widely used. Then in the late 19th century, the company Kimberly-Clark developed Cellucotton. This was made from wood pulp and proved to be much more absorbent than standard cotton.

Cellucotton was used to produce bandages, and during World War I, it was the bandage of choice for the wounded. Nurses, however, found that Cellucotton bandages also made for effective sanitary napkins. Fast-forward to after the war in 1921, and disposable sanitary napkins made of Cellucotton appeared as Kotex –- a name derived from the product's cotton-like texture. Smithsonian notes that the impact of Kotex was that it "jumpstarted the feminine hygiene product market."

Cheetos

As junk food goes, the only thing not to like about Cheetos is orange fingertips. According to "The Oxford Companion to Cheese," our relationship with this cheesy product goes back to World War II, when shelf-stable cheese was included en masse in soldiers' K-rations. The surgeon general ordered that any cheese meant for troops be quarantined for 60 days to reduce brucellosis, a bacterial infection. To store that much cheese required a lot of space, so the U.S. Army invented a dehydrated cheese cake. Dehydration, according to Wired, reduced the volume and weight of the cheese, hence reducing the space needed for storage.

By the end of the war, the government had a surplus of all this dehydrated cheese, which it then sold back to the private sector at a fraction of the cost. The substance found its way to the food manufacturer Frito (later Frito-Lay), who in 1948 introduced Cheetos, the first and possibly most successful cheese snack product in history. But powdered cheese is used to make far more than Cheetos. "Combat-Ready Kitchen" points out that the product is used in boxed macaroni as well as one of toddlers' favorite foods: Goldfish.

Silly Putty

War shortages inadvertently brought joy to millions of children around the globe. Author Tom Quinn's "Science's Strangest Inventions" explains how, during World War II, there was an acute rubber shortage. Rubber was a vital product for the war effort, not only providing needed material for vehicle tires, but also the very boots worn by the troops. According to HowStuffWorks, the War Production Board enlisted the scientific community to come up with a way to make cheap synthetic rubber. All sorts of materials were tried out. James Wright from General Electric was working with silicon and in one experiment combined it with boric acid. The result was a putty, but not just any putty. It was a putty that bounced and stretched. It also made nice copies from newspapers. Wright had, in fact, invented Silly Putty.

The problem was that while it certainly was interesting, there was no practical use for it. So the goo was shelved until 1949, when toymaker Peter Hodgson marketed it as a novelty. Silly Putty had entered the annals of toy legend. It was inducted into the National Toy Hall of Fame in 2001.

Canned Food

Before refrigeration, long-term food storage was a major problem, and it was especially difficult for armies on the move. According to Britannica, the French government led an effort to find ways to preserve food for long periods of time. The result was candymaker Nicolas Appert's invention of canning in 1809. Canning in essence puts a food item in a container that is sealed and heated. The heat kills bacteria and other microorganisms while also creating a vacuum that seals the can and prevents new microorganisms from getting in.

Originally, Smithsonian reports, Appert used glass jars that were corked and then sealed with wax before being boiled in canvas. Interestingly, he did not understand the science behind canning, although he collected a substantial sum in prize money for figuring it out. It took Appert 14 years of trial and error to find a process that worked. It was quickly tested on a variety of foods by the French navy before spreading globally. As for the science behind canning, it was finally explained by Louis Pasteur over half a century later.

Microwave ovens

During World War II, the Allies were heavily involved in the development of radar. In the United States, there were several labs working on the technology; according to the Smithsonian National Museum of American History, one of them was manned by the Raytheon company. One of their engineers was Percy Spencer, who was working closely with radio wave-emitting magnetrons. After working with one he found, to his surprise, that the chocolate bar in his pocket had melted. While Popular Mechanics reports that Spencer's grandson asserts it was a peanut cluster bar, not a chocolate bar, the result is the same: These radio waves could cook. Further tests on popcorn kernels and eggs confirmed this, and the microwave oven was born.

Early microwave ovens were mammoth. The first, 1947's "Radarange," was 6 feet tall and tipped the scales at 750 pounds. It also cost two grand. It took a couple of decades for prices and sizes to shrink enough to make the device so ubiquitous that 90% of homes in the United States have a microwave oven.

Super Glue

Breaking a vase or plate usually results in desperate cries for Super Glue or one of the variety of similar, ultra-sticky adhesives. This product saw its origins during World War II. MIT tells us that in 1942, chemist Harry Coover was on an Eastman-Kodak team researching how to make a clear plastic that could be used for gunsights. While experimenting with acrylic compounds known as cyanoacrylates, Coover found that they made for a very sticky glue because they catalyzed with moisture almost instantly. Since there is moisture virtually everywhere (even in the air), this meant that it would stick almost anywhere. However, the substance was of no use for their project, so they put cyanoacrylates aside and looked at other chemicals.

Fast-forward to 1951, when Kodak transferred Coover to its chemical plant in Tennessee. There he started researching cyanoacrylates again. This led to "Eastman 910," the first name for the product that would become Super Glue. Aside from fixing broken plates, the glue was put to lifesaving use during the Vietnam War, where it was spritzed over open wounds. It instantly stopped the bleeding long enough for the injured to be transported to other facilities. For most of us, though, our use of Super Glue and its many competitor products is thankfully more mundane.

Drones

While flying a drone is a popular hobby these days, their origins are much more bellicose. A drone, according to Britannica, is an unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) that can be controlled remotely or by its programming. The Imperial War Museum tells us that the earliest drone-like vehicles go back to World War I, when both Britain and the United States began to experiment with radio-controlled aircraft. In the years leading up to World War II, primitive drones were used as targets. The technology kept advancing through the Cold War and beyond. Today units fly in various directions, and some even use solar power. The military is looking at ways to make drones the primary attack aircraft in highly dangerous conflicts instead of sending piloted aircraft.

Drones have also been widely adopted by other sectors. They are used to monitor environmental change and are very popular as a tool for digital photography. Whatever the use, they are growing so popular that the FAA has a raft of regulations concerning their use.

Aviator sunglasses

Aviator sunglasses, a popular fashion item for decades, really were invented for aviators. Vogue explains how they got their start as early aviation soared higher and higher and pilots needed to use thick goggles to see properly. The eyewear was heavy and didn't do enough to block the sun in the open aircraft of the day. The New York Times reports that James Macready witnessed the aftermath of a fellow pilot having to take off the goggles at a high altitude to clear off mist. When he did so, his eyes froze over.

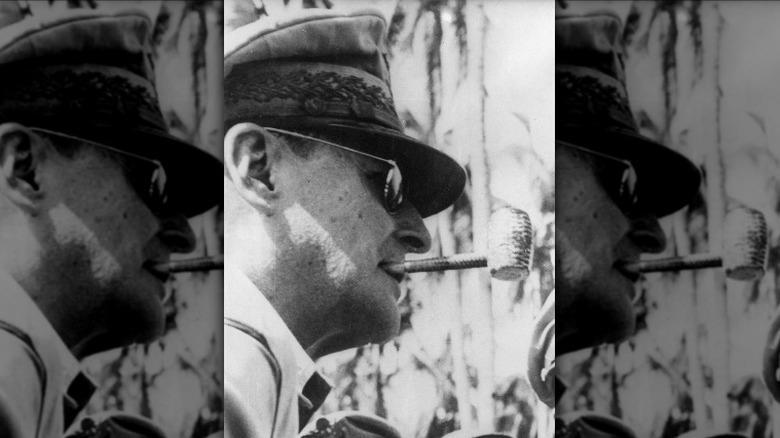

Macready worked with Bausch & Lomb to develop a lighter-weight version of pilot goggles. The BBC reported that this version proved to be effective in protecting a pilot's eyes from the elements. While the design would evolve somewhat, aviator sunglasses had been born. Commercial versions of these "Ray-Bans" entered the market. Still, aviators were chiefly used by the military. It was General Douglas MacArthur, who was photographed wearing a pair when returning to the Philippines after its liberation from the Japanese during World War II, who is credited with bringing aviator sunglasses to the fashion sensibilities of the everyday public. The glasses took off from there and became widely adopted by men and women over the next several decades.

Wristwatches

In any military operation, time is of the essence, so armed forces since time immemorial have looked for ways to keep good track of time. Timekeepers used pocket watches by the 19th century, but in the heat of battle, these devices were far too cumbersome. The New York Times tells us that the more practically designed wristwatch was first worn by women and meant to be a fashion statement. However, the German navy experimented with wristwatches, and according to the Wall Street Journal, wristwatches were used during the Boer War (1899-1902).

A small market for wristwatches developed in the early 20th century, which expanded with pilot watches after the launch of the new field of aviation. But the first general adoption of the wristwatch came during World War I in the form of trench watches that featured a simple design with luminescent hands. It was, in fact, during World War I when the phrase "synchronize your watches" came into common parlance since no soldier wanted to be caught out in the open during an artillery barrage.

Frozen orange juice concentrate

Orange juice is about as common a household item as it gets. This, however, is but a recent innovation thanks to refrigeration and the earnest work of World War II scientists to keep the troops juiced up. The problem back then was that concentration and freezing processes led to the breakdown of the juice's essential oils, making it taste awful. Time relates how, in 1942, the U.S. Army offered a lucrative contract to the innovator that could produce frozen orange juice that tasted like orange juice. From the Army's point of view, it wouldn't just keep soldiers happy; it would be a much-needed source of vitamin C.

The New York Times reported that the Florida Citrus Commission, using a research lab provided by the USDA, set to the task. In 1945, C.D. Atkins, Edwin L. Moore, and L.G. MacDowell arrived at a solution. The trio used the already-established concentration method, which entailed raising the juice's temperature so that water evaporated, but they also used a "cutback process" in which they added fresh juice to the concentrate. The end result was a frozen product that actually tasted like OJ. Thus Big Orange was launched, which climbed to and never left the apogee of the breakfast juice world.

Jeep

Today, Jeep is a major brand of automobile known for its rough-and-ready vehicles that can handle any terrain. So it should be no surprise that Jeep has its origins in the Army, back when the organization was seeking a lightweight reconnaissance vehicle. Autoweek describes how, prior to America's entry into World War II, the U.S. Army was rightly worried that the United States would be drawn into the conflict. War planners realized they needed a vehicle that was fast and agile enough to handle all sorts of terrain. They issued a request for proposals, with a tight deadline. A small carmaker, the American Bantam Car Company, responded with the first Jeep prototype.

This prototype, which was designed by freelance engineer Karl Probst in just 18 hours, did extremely well. However, in order to ramp up production, the War Department enlisted automakers Ford and Willys-Overland to bid for the contract based on Probst's design. The final version of the Jeep included elements from all three companies, and over 637,000 were built during the war. Afterward, as told by Car and Driver, Jeep entered the civilian market. Even though the brand and vehicle were popular, its corporate history was fraught with mergers and losses, usually due to failures of other brands or bad management. Jeep, however, keeps selling.

EpiPen

If you do not know what an EpiPen is, then you are probably not one of the 200,000 people who visit an emergency room every year due to food allergies. EpiPens are designed to treat anaphylaxis shock, which, according to Healthline, is when somebody has a severe allergic reaction, usually to food like nuts but also to bee stings or materials such as latex. Anaphylaxis is sort of like the body going to Defcon 4 when there is no threat. The result can be death as blood pressure drops and air passageways are cut off. The EpiPen saves lives by quickly delivering a self-administered shot of adrenaline to the thigh with an autoinjector that works on a spring-loaded mechanism. This raises blood pressure and opens airways.

However, it wasn't for anaphylaxis that the EpiPen was invented. According to the National Inventors Hall of Fame, inventor Sheldon Kaplan created the EpiPen at Survival Technology, Inc. in the 1970s as a way to deliver nerve agent antidote in combat situations. Yet its civilian use was immediately apparent. Thus, for the military, the ComboPen was born, while civilians got the EpiPen.

T-shirts

For T-shirts, we have to thank the U.S. Navy. This simple shirt's story begins, according to Gizmodo, in the 19th century with "union suits." These were one-piece red flannel affairs, complete with a posterior flap, that were popular among the working set. Eventually, some enterprising proletarian decided to cut it in half since the one-piece was too hot in warmer weather. This created "Long Johns."

Fabric choices and experimentation led to an undershirt that was adopted by the U.S. Navy into its uniform. The thinking was that they were simple, easy garments without buttons. It was perfect for the many young, single men who joined the Navy. By regulation, a monochrome undershirt had to be worn under the uniform –- white turned out to be the chosen color. This then became the working shirt in warm weather. During World War I, it was widely adopted by the Army. The T-shirt quickly filtered through most of American culture and really got a boost with Marlon Brando's character Stan Kowalski wearing a tight-fitting one in 1951's "A Streetcar Named Desire." T-shirts may very well be the best-selling clothing item in the world.