What Living In New York City 100 Years Ago Was Really Like

New York City boomed in the early 20th century — by 1920, the city's population had increased 124% over the preceding three decades (via ICHP). As New York entered the so-called "Roaring Twenties," the "Big Apple" brimmed with activity while it constructed much of its modern identity. Indeed, the term "Big Apple" was coined in 1921 by sportswriter John J. Fitz Gerald.

The opportunities offered in New York City during this period caused its population to swell beyond London's, becoming the most populated city in the world (via ThoughtCo). While average unemployment stayed under 7%, wages and living standards rose across the board, according to Living City Archive. Some workers, such as those employed by the Ford Motor Company, enjoyed greatly improved living standards when compared to the turn of the century, in homes replete with electricity, central heating, running water, and toilets.

However, with newfound wealth came newfound inequality. Some lived a "Great Gatsby" existence, while many others struggled from job to job, living in decrepit tenement buildings. New York City was, like now, a buzzing mass of extremes and contradictions. So, from booze and jazz, to gangsters and even terrorists, here is what living in New York City 100 years ago was really like.

The First World War changed New Yorkers' attitudes about life

The United States may have entered the First World War a year before the conflict ended, in 1917, but the nation still mobilized 4 million soldiers, over 100,000 of whom died from combat or disease. Another 204,000 were wounded, and they had to re-enter American society with often very visible injuries (via History on the Net).

The horrors of that conflict changed American attitudes and shaped much of what came to define the Jazz Age and the Roaring Twenties, namely a loosening of morality and questioning of traditional American values such as family, work ethic, and the church (via Encyclopedia). New York City was at the forefront of this cultural shift, especially in the arts. After the vaudeville fare of the late 19th century, playwright Eugene O'Neill brought serious dramas to Broadway, which explored everything from materialism and idealism to murder and violence — reflecting a society that was jaded by conflict and reappraising the purpose, and realities, of life.

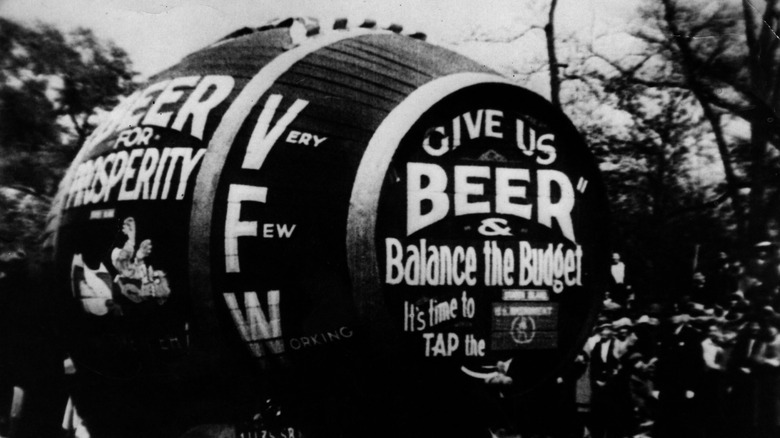

Alcohol was illegal

According to Britannica, the Volstead Act came into effect in 1920 and was enforced for 13 years, until it was repealed by the Roosevelt administration on December 5, 1933 (via History). Booze may have been illegal, but that did not stop its gleeful consumption. Like scores of Americans across the country, New Yorkers quenched their thirst in thousands of speakeasy bars hidden throughout the city. By 1930, New York City was home to an estimated 32,000 speakeasy clubs, according to New York magazine. The etymology of "speakeasy" is straightforward since, according to the Online Etymology Dictionary, the term referred to the practice of speaking quietly, or "easy," about the establishments to avoid raids by the police and FBI.

Speakeasies came in all shapes and sizes. Some were plushy decorated with jazz bands and dance floors, while others were shady basements and backrooms (via Mob Museum). Of the many speakeasies scattered across New York City, one of the most notable was Chumley's, established at 86 Bedford Street in 1922 by Leland Stanford Chumley. The former blacksmith shop became a popular watering hole for writers, journalists, and poets, such as F. Scott Fitzgerald, Ernest Hemingway, and J.D. Salinger. Unlike many prohibition bars, which closed en masse following alcohol's re-legalization, Chumley's continued for almost another 100 years. In 2016, the joint reopened after repairs with a new sophisticated vibe, but Chumley's would finally shut its doors for good in July 2020, as a result of that year's COVID-19 lockdowns.

Cars had arrived, but horses were still commonplace

The predecessor to the modern automobile was invented by Gottlieb Daimler and Karl Benz, but it was the Ford Model T that brought motoring to the American masses, transforming New York City. Beforehand, in the 19th and early 20th centuries, horses had dominated the city's streets. In fact, between 100,000 and 200,000 horses lived in New York during that period, producing literally tons of manure each day (via New York Times). Piles of dung would attract clouds of flies that, according to Appleton Magazine, caused "maladies that fly in the dust," killing up to 20,000 New Yorkers annually — the car greatly reduced this problem.

According to economic historian J. Bradford DeLong, the United States produced 3.5 million cars in 1924, vastly greater than France, Britain, and Germany combined. High output and low prices — a Model T cost just $310 in 1921 — saw widespread adoption of the motorcar. By 1929, four in five families owned a car (via World History).

Of course, cars brought problems of their own. On September 13, 1899, the New York Times reported the first fatal car accident in the United States, which occurred in Manhattan at Central Park West and West 74th Street. By 1915, the same paper was reporting on multiple fatal collisions in a single day. In the 1920s, New York City began holding parades with thousands of children dressed as ghosts, representing the young deaths that were plaguing the city's unregulated roads (via Detroit News).

Many of New York's most enduring restaurants were already present in the 1920s

Many of New York's most enduring culinary institutions predate the 1920s. For example, the famous Peter Luger steakhouse in Brooklyn was founded decades prior, in 1887, making it the third-oldest steakhouse in the city after Keens, which opened in 1885, and The Old Homestead, who opened their doors in 1868. Also present was Lombardi's, the first pizzeria in the United States; Delmonico's, the first fine dining restaurant in the United States; and Rao's, the celebrity favorite known for its 10-table layout and invite-only setup. Katz's Delicatessen was also doing business, having been established by Jewish immigrants in 1888.

However, the 1920s gave rise to a slew of New York classics, too. John's Pizzeria with its thin-crust pies and Coney Island's Totonno's, purveyors of no-nonsense garlicky pizzas, were both founded in the decade, as was the former speakeasy 21 Club, which was frequented by New York's movers and shakers for some 90 years before it closed its doors in 2021 — another victim of the widespread business closures during the COVID-19 pandemic.

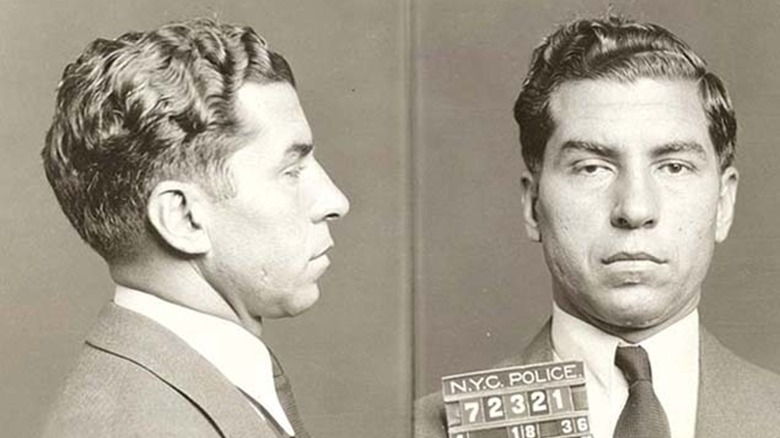

Criminals had their fingers in many pies

According to History, the notion of "organized crime" was not discussed by the press, public, and lawmakers until the 1920s, when prohibition handed immensely lucrative opportunities to New York City's career criminals. Figures such as Lucky Luciano, Meyer Lansky, Salvatore Maranzano, and Frank Costello were ready to meet the demands for beer, wine, and liquor (via Mob Museum).

As alcohol production went underground, these men and their underlings became the enforcers and security for bootlegging operations across New York City and the United States. They would use their money to pay off the law and their guns to fend off the competition. Prohibition generated vast illicit wealth, creating a new class of criminal, with lawyers, accountants, and extensive money laundering operations. In 1920, Lucky Luciano held a meeting between New York City's most powerful mobsters in a bid to work together as businessmen, rather than thugs and murderers. It was also in this criminal milieu that Arnold Rothstein, a sophisticated criminal operator who smuggled alcohol to New York's many speakeasies, allegedly fixed the 1919 World Series.

Terrorism was a threat

Terrorism, like today, was a threat to New Yorkers 100 years ago. On September 16, 1920, a bomb was detonated on Wall Street, instantly killing 30 people and wounding 10 times more (via FBI). The explosive had been transported by a horse and cart, stopping outside the J.P. Morgan before exploding, sending 500 lbs of metal fragments through the air, according to Slate. One eyewitness said that the blast was so powerful that it derailed a passenger trolley two blocks away.

The attack on Wall Street occurred some 15 months after a spate of anarchist bombings across the United States (via History). During the spring of 1919, explosives were sent to Thomas Hardwick, a former U.S. senator from Georgia, and Seattle mayor Ole Hanson. The latter bomb failed to detonate, but Hardwick's exploded, inflicting serious injuries. Dozens of further mail bombs would be intercepted, with prospective victims including John D. Rockefeller, J.P. Morgan, and Oliver Wendell Holmes.

In New York City, suspecting the Wall Street attack to be the work of Italian anarchist Luigi Galleani, city and federal authorities were tasked with finding the bombers. Extensive eyewitness interviews proved to be a dead end. However, several flyers written by the "American Anarchist Fighters" were found near the bombsite, which were very similar to those found in the attacks of 1919. Despite this evidence, the perpetrators were ultimately never found.

Many African Americans settled in New York City as part of the Great Migration

During the 1920s, some 200,000 African Americans, many from the South, settled in New York City's Harlem neighborhood (via All That's Interesting). They arrived in the city because it offered opportunities and a freer culture. In the Southern states, jobs for African Americans rarely extended beyond agriculture, a restriction that was enforced by law (via History). Black people were also severely victimized by the Ku Klux Klan, which was a formidable force in the South that reached some 4 million members during the 1920s, according to Britannica.

However, life in New York City was by no means easy, especially the housing market. Some white neighborhoods formed covenants that agreed to not sell or lease property to the growing African American community, which caused much tension and resentment. The "Great Migration" continued, though, and did so right up until 1970, when the full extent of the exodus could be measured. In 1900, 90% of African Americans lived in the South. After 70 years, just half of the country's African American population lived in the South.

Historian Nicolas Lemann wrote in "The Promised Land" that the Great Migration was "one of the largest and most rapid mass internal movements in history" and "perhaps the greatest not caused by the immediate threat of execution or starvation ... In sheer numbers, it outranks the migration of any other ethnic group — Italians or Irish or Jews or Poles—to the United States."

Jazz become popular

With the "Great Migration" — the mass movement of African Americans from the South, to northern cities such as New York — came jazz, which had flourished across New Orleans in the late 19th century. According to The Conversation, the genre was later popularized by Jelly Roll Morton through innovative use of recording technologies, spreading the sound of Louisiana jazz beyond the fringes of the "Big Easy," a name given to New Orleans because it was so easy for musicians to find work there.

Yet this publicity would be dwarfed by Harlem, which became a new hub of jazz and other musical styles. Harlem's nightlife was represented most famously in two venues: the Savoy, a ballroom with jazz into the small hours; and the Cotton Club, which catered for white audiences, inviting the scorn of those who felt it to be inauthentic, and encouragement from others who saw it as an "acceptance" of African American culture (via History). Known as the Harlem Renaissance, the cultural boom spanned the 1920s, acting as a crossroads of race and culture during prohibition until 1929, when the stock market crashed and the Great Depression commenced. Remnants of the zeitgeist continued until the end of prohibition in 1933, which stemmed the flow of white patrons seeking speakeasy booze.

Poverty was rife

The post-war economic boom created disposable income for many Americans, who could spend it on new products such as radios and cars, such as the new Ford Model T (via History). However, in New York City, standards of living were starkly divided. According to the Journal of American History, inequality was greater in 1920 than it was in 1890. Urbanization, immigration, and industrialization had created great wealth, but had also formed a large proletariat who endured harsh conditions, both at home and at work (via ICPH). Many of these people lived in tenement buildings that were infamous for their filth and lack of amenities.

Conditions in tenement buildings were improving somewhat by the 1920s, but slowly and with much reluctance from landlords. It was only in 1918 that the installation of electricity became legally required (via All That's Interesting). Toilets were a fairly recent innovation too, having been mandated by the city's government in 1904. Tenement living, which existed notably in the Upper West Side and Lower East Side of Manhattan, continued through the 1920s and into the 1930s, when Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal revolutionized low-income housing across the country. According to History, New York City's first public housing project — called "First Houses" — was opened in 1936. Still, even with government intervention, life in the "First Houses" was quite different to those just blocks away.

Wealth and corruption abounded

F. Scott Fitzgerald's novel "The Great Gatsby" was set in 1922 New York, and it typified the hedonism of the era. Perhaps American literature's greatest social history novel, Fitzgerald also lived the life he depicted in "The Great Gatsby." Following the rapid success of his first novel "This Side of Paradise," the 24-year-old Fitzgerald was able to lead a playboy lifestyle that abounded in wealth and indulgence — the habits, customs, and consequences of which he would explore in "Gatsby," his third novel (via Biography).

The characters in Fitzgerald's life and novels were part of an American elite that possessed a historically large share of the national wealth, a trend that we are seeing a century later. Economics professor Gabriel Zucman said in 2019, "U.S. wealth concentration seems to have returned to levels last seen during the Roaring Twenties." Corruption and financial self-interest were rife at the highest levels of government, too. Indeed, James J. Walker, mayor of New York City from 1925 to 1932, was described by Britannica as "a playboy addicted to the wonders of city nightlife."

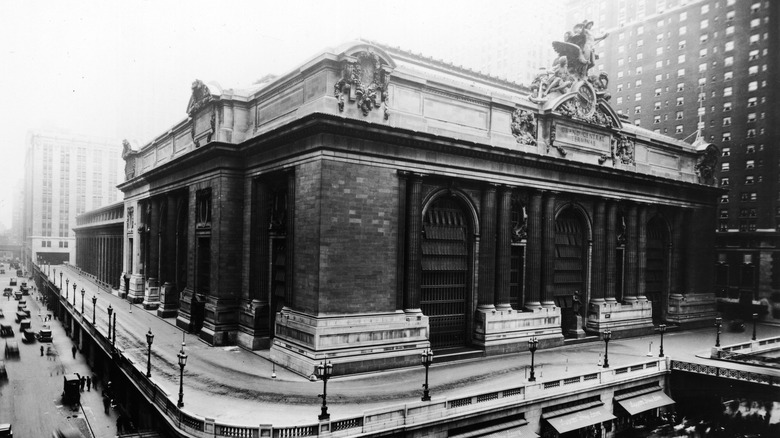

Grand Central Terminal was transforming Midtown Manhattan

Prior to the 1920s, downtown Manhattan had always been the dominant force in New York's economy, relegating Midtown to secondary status. However, the opening of Grand Central Terminal in 1913 transformed the area (via Entrepreneur). William J. Wilgus, the engineer who oversaw the project, realized it as not just a transportation hub with shops, hospitality, and other enterprises, he also effected the regeneration of Park Avenue.

Perhaps the most obvious development in the area was Times Square, which grew into its role as one of New York's main public squares. Greater footfall from Grand Central Terminal helped in this development, but it was also aided by the advent of neon signage, first displayed by Georges Claude at the Paris Motor Show in 1910, according to North American Signs. In 1923, Claude took the colorful technology to the United States, making two sales to a car dealership in Los Angeles. Soon, Claude's neon signs had spread across the continent, manifesting in Times Square, now perhaps the world's most famous display of neon signage. Times Square's popularity lasted from the 1920s through to the 1960s, by which time its vibe and aesthetic had degenerated. The area was a hotbed of crime until the 1990s, when it was cleaned up during Rudy Giuliani's mayorship, recreating Times Square in a new "corporate" image (via Britannica).