Non-Binary Figures In Mythology

Trans and non-binary people have always been part of human society. As Human Rights Watch notes, this is shown by historical records dating back over 7,000 years. Humans are natural storytellers, and ancient cultures used myths and legends to explain facts, both about nature and culture. The stories told in a society reflect and inform the beliefs and values of the people telling them in the modern world just as in ancient times – and as Pride explains, human history is awash with stories of people who defy binary gender.

It's important to be cautious when interpreting ancient cultures, as modern concepts like LGBTQ+ don't necessarily apply. Modern concepts, like lesbian or transgender, don't fit properly when applied to the ancient world, but neither do concepts like heterosexuality. A study in the Theoretical Roman Archaeology Journal discusses this, noting that the view of modern archaeologists is influenced by a modern view of binary gender which can easily gloss over intersex and non-binary people from the ancient world. Difficulty in interpreting the past can even happen when studying ancient writings. As a faculty paper from Linfield University explains, sometimes older texts contain characters with clear fluid or ambiguously gendered characteristics but lack the words to properly describe them.

Keeping this in mind, there are plenty of figures from mythology who don't fit into the modern Western gender binary. Some were transformed by magic or curses. Some are tricksters who change genders at will. Some were, as the song goes, born this way.

Asushunamir

Possibly the first non-binary figure in written history comes from ancient Mesopotamia, one of humanity's first civilizations. Their name, Asushunamir, literally translates as "whose appearance is radiant." In the book "An Anthology of Ancient Mesopotamian Texts," Asushunamir is described as an assinu, with no further elaboration. Dr. Moudhy Al-Rashid, an Assyriologist at Wolfson College Oxford, explains that an assinu was a gender-fluid person. As author Devdutt Pattanaik elaborates, Asushunamir was created to be neither male nor female.

As such an old legend, are a few different variants and translations of the story. One, succinctly summarised by Overly Sarcastic Productions, begins with Ishtar heading to the underworld to reunite with her dead husband Tammuz. She passes through the seven gates of the underworld but finds herself trapped there. She is imprisoned by Ereshkigal, the goddess of the dead, and afflicted with 60 diseases. The god Enki then creates Asushunamir to charm Ereshkigal with their good looks before stealing the water of life to resurrect Ishtar. The two escape, but not before Asushunamir and everyone like them are cursed to be ostracised from society. For rescuing her though, Ishtar grants Asushunamir the powers of prophecy and healing.

Ishtar seemingly retained an association with gender variant people in the ancient world. As World History Encyclopedia explains, members of Ishtar's priesthood were often transgender and bisexual. People we'd recognize today as trans women and trans men were called kurgarra and galatur, created by the gods to be neither male nor female.

Dionysus

The Greek god of wine, Dionysus had a long history. As Overly Sarcastic Productions explains, his story and characterization gradually changed throughout the history of the ancient world. Bust notes that some versions of Dionysus played with the god's gender. One story talks about how he was born male, dressed in women's clothes in adolescence, and later rejected any gender identity at all.

This rejection of cultural norms fits perfectly with the Cult of Dionysus in Ancient Greece, whose ethos was all about self-expression and rebelling against polite society. As Britannica explains, this was a mystery cult, a secret community into which people could be initiated if they wanted a break from the usual societal bounds. Theoi elaborates further, that people in the Classical and Hellenistic eras depicted Dionysus as pretty, youthful, effeminate, and frequently drunk.

A page from the University of Liverpool's Department of Archaeology, Classics, and Egyptology discusses how Dionysus can be used to highlight the way both gender and sexuality could be fluid in the ancient world, challenging the idea that non-binary gender identities are a new invention. Notably, ideas of fluid gender and sexuality were seemingly much more accepted in Ancient Greece than many people in the modern world might believe them to be. However, as Autostraddle points out, Dionysus' gender-bending identity wasn't universally accepted there either, and perhaps that may have been the entire point. The Ancient Greeks loved categorizations, but Dionysus and his followers took great delight in refusing to conform to society.

Loki

Loki is now famous for his appearance in the Marvel comics (and from the films based on them, where he is played by Tom Hiddleston), and his comic persona has become well known as one of the most prominent genderfluid characters in the world of comic books. This, however, is no modern creation. The figure from Norse mythology didn't fit into binary gender either.

The version of Loki from ancient legend was a shapeshifting trickster, able to change both his appearance and gender at will. Loki also seems rather more enigmatic than other Norse Gods, with no evidence of a cult of followers, and no places named after him. In Norse mythology, Loki often appeared alongside Thor and Odin, sometimes as an ally and sometimes as an antagonist, in a characterization that will be familiar to comic fans. A conference paper published by Advances in Social Science notes that the real Loki even had giants as ancestors.

A prominent story in the "Prose Edda" involves Loki transforming into a woman to trick the goddess Frigg, learning the weakness of Odin's son Baldr. While always being referred to with masculine pronouns, some stories even see Loki become pregnant. A story mentioned in "Norse Mythology A to Z" sees Loki become the mother of Odin's 8-legged horse, Sleipnir. Another book, "Old Norse Religion in Long-term Perspectives" mentions other female figures who Loki disguised himself as, a giantess named Thökk and a milkmaid in the epic poem Lokasenna.

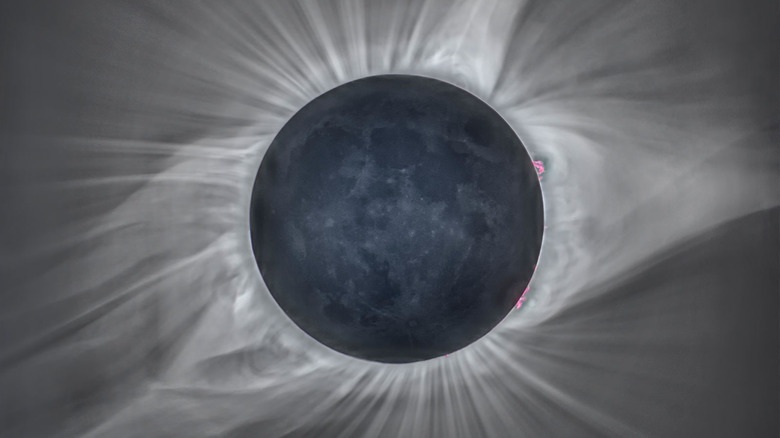

Mawu-Lisa

In the belief system of the Fon people of West Africa, the world was created by a bigender deity. Mawu-Lisa, as a paper in the Journal of Religion in Africa explains, is a fusion of two gods, the male god Lisa, associated with the Sun, and the female god Mawu, representing the moon. The resulting dual god, Mawu-Lisa, is both male and female at the same time. The two are twins, and the two combining in harmony represents order in the universe. To create the world, Mawu-Lisa worked together with another god known as Da. Another bigender deity, Da is represented by a rainbow. Seemingly, non-binary deities are welcome in the pantheon of the Fon. While Mawu-Lisa is a creator god, there are also stories of an even older androgynous god who preceded them. As Oxford Reference mentions, this original god is named Nana Buluku, and they were the one who created the creator!

The motif in Fon culture of two seeming opposites combining to work in harmony is a motif that is shared by the culture of many other peoples across the world. In Chinese mythology, the primordial goddess T'ai Yuan was said to embody both Yin and Yang, the feminine and masculine forces which sustain the cosmos. Similarly, in North America, the Zuni have a creator deity Awonawilona, who is also both male and female. The idea of a non-binary creator deity is a concept that recurs over and over in human culture.

Inari

One of Japan's national religions is Shinto, which involves the worship of Kami, variously translated as either spirits or gods. These are the gods referred to throughout the Studio Ghibli movie "Spirited Away," but one particular kami stands out as having no fixed gender. A Kami named Inari, the god of rice. According to Britannica, Inari has depictions ranging from a woman with long flowing hair carrying sheaves of rice, to an old man with a white beard riding a white fox. They are one of the most important Kami in Shinto and, as Japan Guide explains, there are thousands of shrines to Inari across Japan, including the famous Fushimi Inari shrine in Kyoto. Known respectfully in Japan as O-Inari-san, Fushimi Inari is ancient, predating Kyoto's rise to be the old capital of Japan in 794 C.E.

Tanken Japan mentions that Inari is a shape-shifting spirit who is also paid respect by Japanese Buddhists. As well as their male and female forms, Inari can also appear as an androgynous bodhisattva, or as various animals including snakes and dragons. Inari is also notable for their strong association with foxes. Known as kitsune (狐) in Japanese, foxes are also seen as shapeshifting and morally ambiguous tricksters, and Inari shrines across modern Japan can be easily recognized by the stone fox statues standing guard at their entrances. However, as the book "Glimpses of Unfamiliar Japan" notes, you're unlikely to ever see a depiction of Inai themself at one of their shrines.

The Tonsured Maize God

Just as the god of rice is an important figure in Japan, the god of maize was an important figure in pre-colonial Mesoamerica. Specifically, the Tonsured Maize God (also known as the Foliated Maize God) was a figure from Mayan mythology, depicted across Central America, as World History Encyclopedia explains. Usually referred to as a man, the Tonsured Maize God is depicted as eternally young and attractive, ornamented with jade, and with long flowing hair like corn silk. However, as a chapter in the book "Ancient Maya Women" explains, there's good reason to believe that Mayan society recognized a third gender, and the Maize God is seemingly a big part of this.

An essay by archaeologist Caroline Seawright explains that in Mayan mythology the gods weren't as clearly defined as in cultures around the ancient Mediterranean. Instead, the gods were sacred entities who overlapped with each other. The Maize God was sometimes conflated with the Moon Goddess, becoming an ambiguously gendered figure, and sometimes considered a third gender. As a compounded gender of the gods, superior to the earthly gender binary, Mayan elites would try to symbolically mimic the non-binary Moon-Maize deity. As History on the Net mentions, nobles in Mayan culture had a near-priestly role in society, considered to be intermediaries between earthly people and the gods, tasked with a duty to both. Rulers of Mayan society, both male and female, would show off divine power by impersonating the Moon-Maize god, gender and all.

Aphroditus

Perhaps the best known legendary non-binary figure is Aphroditus, from Greek Myth. They were an ambiguously gendered version of Aphrodite, the goddess of love. As Bust explains, Aphroditus was a fertility god, with the appearance and silhouette of a woman but with phallic genitalia. They were seen as a harmony of male and female. Fittingly, festivals of Aphroditus usually involved men and women swapping both their clothes and their gender roles.

Aphroditus would later become known as Hermaphroditus who, as Theoi explains, was a winged love deity, one of many known as Erotes. Hermaphroditus was said to be the child of Hermes and Aphrodite, the gods of male and female sexuality. As their child, Hermaphroditus inherited their beauty from both parents, as a divine fusion of masculine and feminine characteristics. As with so many figures from mythology, Hermaphroditus is neither man nor woman, but both at the same time.

The deity Hermaphroditus is where the word hermaphrodite comes from. It's important to remember that, as the University of Hawaii notes, this term is now considered highly offensive when used to refer to people. In Ancient Rome, however, the word hermaphrodite referred to a legally recognized third gender. As a paper in the Journal of the Savigny Foundation for Legal History explains, while the early Romans had a dim view of anyone born with intersex characteristics, Roman law eventually came to recognize "hermaphroditi" as a distinct gender, separate from men and women.

Bathala

The Philippines is one of the friendliest countries in Asia for the LGBTQ+ community. As an article in Making Queer History mentions, this acceptance goes back a long way, with its origins in Tagalog mythology. The pre-colonial Philippines had a pantheistic religion with strong homosexual and transgender themes. One figure, in particular, is named Bathala. With a name meaning "man and woman in one," Bathala can be considered either intersex or non-binary.

Tagalog Lang explains that Bathala was considered the highest deity of the Tagalog pantheon, and the creator of the world. He's likely behind the commonly used Filipino phrase "bahala an," meaning "let whatever happen," a saying which can be used as much in uncaring resignation as in relentless courage. A full version of the Philippine creation story is recounted by The Aswang Project, although unfortunately most surviving documentation about pre-colonial Philippine mythology was written by the Spanish colonizers themselves.

Bathala wasn't the only gender variant deity in Philippine mythology either. According to the Southeast Asia Queer Cultural Festival 2021, while Bathala is considered to be ambiguously gendered, a deity named Makapatag-Malaon was explicitly both male and female and the highest deity of the Waray people. Additionally, the goddess Lakapati was the consort of Bathala, and also a trans woman. The people of the pre-colonial Philippines evidently celebrated diversity in gender.

Arjuna

Hindu mythology is another place that prominently features gods who're both male and female. One example is Ardhanarishvara, whose name means "lord who is half woman" in Sanskrit. In Hindu mythology though, mortals can be non-binary as well. The Free Press Journal recounts the story of Arjuna, a major character in the Mahabharata, an epic tale from Ancient India.

The story goes that Arjuna rejected the affections of a celestial maiden named Urvashi. In anger, she placed a curse on Arjuna, transforming him into a member of the third gender. Far from seeing it purely as a curse, Arjuna uses this magical transition as a disguise while he is in exile, wearing women's clothes, taking the name of Brihannala, and becoming a teacher of music and dance. Another story shows Arjuna transformed into a woman and taking part in a mystical dance that men aren't allowed to join.

Arjuna's story is far from the only reference to a third gender in Hindu scripture. As The New Indian Express emphatically states, Hindu texts are full of references to the third gender. This ties in with a group of third-gender people in modern-day India, known as Hijras. Harvard Divinity School explains that Hijras consider themselves distinctly neither male nor female, and there are millions of Hijras living in 21st-century India. While they're largely ostracised and victimized by the modern world, non-binary people have been important members of Indian society for over two millennia.

The Rainbow Serpent

Indigenous people across Australia share some beliefs in common, and a widely revered figure among them is the Rainbow Serpent. As Artlandish explains, the Rainbow Serpent is an immortal being and a creator deity, with countless associated names and stories. The book "Gender and Identity around the World" discusses how the Serpent is referred to variously as genderless, androgynous, transgender, or genderfluid. They're believed to be the source of all rivers and water, as well as symbolizing fertility. Their connection between rainbows and water alludes to the ever changing seasons and the great value of water to all of life, and the Serpent's presence is used to explain why some water holes never go dry, even in droughts. Among Native Australians, the appearance of a rainbow in the sky is said to be the Serpent traveling from one water hole to the next.

Australia, with hundreds of distinct groups of native peoples, is home to some of the world's oldest cultures. The beliefs among Native Australians are no less diverse, and not every group shares the same spirituality. The Rainbow Serpent, however, is nearly ubiquitous. As a study in the journal Archaeology in Oceania notes, they're considered one of the most powerful and important ancestral beings in Australia. With oral histories going back thousands of years, the Rainbow Serpent may have the longest history of any non-binary mythical figure in the world.