What Hygiene Was Like In Colonial America

The average person spends up to an hour every day tending to their personal appearance (via Statista.com). There is so much to labor over to achieve that flawless look: hair must be tamed, faces need exfoliating, teeth must flossed and brushed, skin must be scrubbed -– and all this before donning a clean outfit for the day. Grooming and personal hygiene have certainly had their evolution (and regression) over the centuries.

Colonial America was a period when no two physicians could agree on the health benefits of bathing let alone how to treat patients when they fell ill. Garbage was routinely slopped into the streets, and yet colonial people rarely thought to scrub up with soap and water.

Ask yourself, if everyone around town reeks of putrid body odor, do you really notice your lack of hygiene? Colonists in America had a very different concept of what cleanliness looked and smelled like. By conventional standards, people in colonial times were downright filthy.

Only the extremely affluent would take baths

Daily bathing as a practice is something we take for granted in modern times. After all, most of us engage in some sort of ritual that involves standing under a stream of hot water or sliding into a tub to wash away any trace of body odor and grime. Back when America was just a series of colonies, hardly anyone took a bath unless it was for medicinal purposes, and it was an activity mostly reserved for the wealthy.

It was not common even among the wealthy in part because of all the effort needed to obtain the water and carry the tub. According to historians at Colonial Williamsburg, wealthy individuals in the colonies only bathed in a tub sparingly throughout the year.

Taking a bath meant someone had to haul a heavy wooden tub out of storage, then collect enough water from somewhere (assuming you had a well nearby), and then possibly heat it. Putting aside all the effort one needed to wash up, people back then were under the impression that removing your body oils could make you vulnerable to sickness.

Some elite people did have bathhouses on their property, but they were not for hygiene. Historians at Colonial Williamsburg report that the last royal governor of Virginia, Lord Dunmore, had one installed at his home. He could not stand the hot climate and would cool off in his bathhouse by having servants pour water over him. No soap was involved.

Changing your underwear was enough to make you clean

One concept of personal hygiene seems to have persisted since Colonial times, and that is the idea that one should wear fresh undergarments. However, people from this period thought that wearing fresh underwear was part of what qualified a person as "clean." Alexander Hamilton famously subscribed to this notion and was known to change into clean undergarments multiple times a day during hot weather (via History Collection).

Colonial people believed undershirts, shifts, and other undergarments could absorb all the sweat and grime from one's skin, as historians at Colonial Williamsburg report. The well-to-do had numerous supplies of clean undergarments laid out for them daily.

According to W. Peter Ward in "The Clean Body: A Modern History," affluent members of society were more worried about the appearance of being clean. Sporting crisp unsoiled white linens were enough evidence to society that a person was hygienic.

Ward writes that the obsession with showing one's cleanliness led to the fashionable trend of displaying one's linens peeking out of collars and shirt cuffs. It became more than being clean, it was an ostentatious display of status.

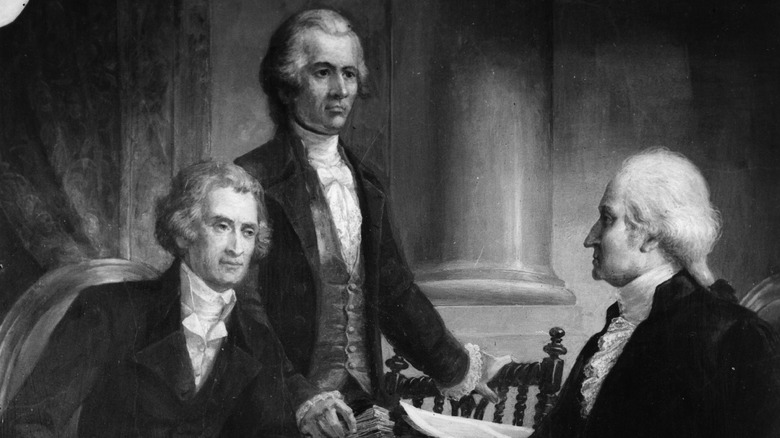

Each Founding Father had their own routine

To prove how varied people have always viewed personal hygiene, you can look no further than the founding fathers. Each man had their own unique approach to cleanliness and personal hygiene, with George Washington and John Hancock being the most dedicated to the practice.

According to History Collection, both men were unusual in that their daily routine included washing themselves head to toe. Hancock used his army of servants to set up his bath every day and even topped off his ablutions with cologne. Washington similarly had his servants wash him with soap and water from a basin each morning. He didn't stop there — he was known to frequently wash his hands before meals too.

The History Collection reports his compatriots were not as keen on such elaborate washing rituals. John Adams was content to just wash his face, neck, and hands with cold water. Thomas Jefferson would partially wash his body with water, but never with warm water. The least hygienic was Thomas Paine, author of "Common Sense," who had a reputation for never washing anything on his person and keeping a filthy home.

Benjamin Franklin had the most peculiar approach to hygiene. Franklin would frequently espouse the benefits of marinating in bathtubs, and he often bathed in rivers as a young man. He enjoyed a stiff breeze on his rosy cheeks too. He bathed with air (yes, you read that correctly) by standing naked near a window, regardless of the season.

Native Americans thought Pilgrims were gross

When the Pilgrims arrived in Massachusetts they disgusted the Wampanoag tribe that inhabited the area. The Wampanoag engaged in daily habits of washing in the river and felt their new invading neighbors were filthy and putrid (via History). In the Pilgrim's defense, they had spent months at sea crammed on ship with limited freshwater.

According to Smithsonian Magazine, the Native Americans were not just repulsed by the smell of Europeans. They found it bizarre that a person would keep a used handkerchief in their pocket rather than dispose of it. Honestly, some people today would share their opinion with equal disgust.

Tisquantum, also known as Squanto, helped educate the European newcomers on how to survive in their new environment. Of all the lessons the Pilgrims took to heart, hygiene was not one of them. In the biography "Squanto," author Feenie Ziner writes that Tisquantum tried to get them to bathe and learn to wear bug repelling oils but ultimately was unsuccessful.

Considering that Pilgrims and Puritans viewed sex as a reviled act only meant for reproduction, and that nudity was a source of shame (via Huff Post), Tisquantum was fighting an uphill battle. Perhaps if he had succeeded it could have prevented the spread of certain diseases that would plague the territory.

Laundry day was nothing but backbreaking work

Today, laundry is just yet another tedious chore involving the gathering and separation of linens and garments to be tossed unceremoniously into the washer with your detergent of choice. An hour later you are graced with fresh clothes. While the ritual of cleaning one's unmentionables has hardly changed much over the centuries, the amount of effort to complete the task has.

Laundry was intense labor often performed by women, as historians at Colonial Williamsburg report. Much like today, houses in the 18th century had a dedicated room, usually near the kitchen where servants or enslaved women would clean the household's linens. Over time the laundry was placed in its own building, as was the case for affluent families.

Laundresses' tools of the trade included lye soap, large tubs for washing and rinsing, a large pot to boil water in, and different types of irons and brushes. They vigorously beat cotton and linens with a small paddle until the dirt was released after boiling them in massive pots (via Thought Co.).

Clothes fashioned from wool or silk underwent a much milder dry cleaning process. A laundry maid would use something called fuller's earth clay to absorb any oily residue from wool, and silk garments were spot cleaned using a variety of things. Colonial Williamsburg historians reveal that salt, chalk, turpentine, lemon juice, and even urine would be employed to tease out any stains.

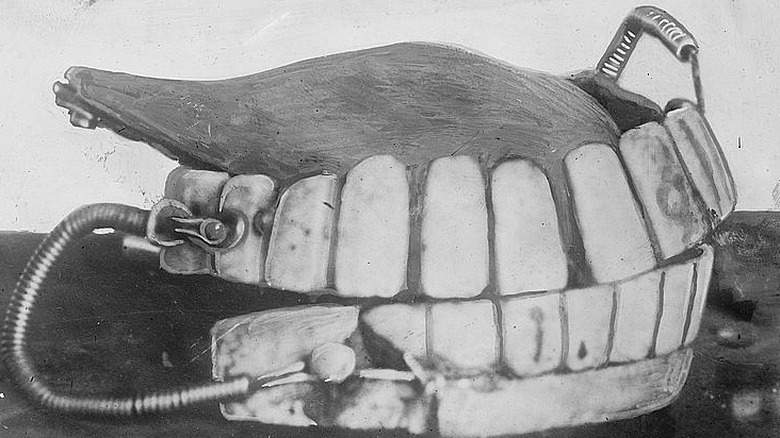

How people took care of their teeth

Dentistry in the 1700s was as rudimentary as it could get. There were dentists, but they had just started exploring how to go about tending to rotten teeth and other issues. Around this time, everyday people were suffering from the effects of different diseases and the abundance of sugar-laden foods, as per Revolutionary War Journal.

For the majority of society, people cured a bad toothache by getting it pulled out by whoever was available: a blacksmith, silversmith, doctor, or barber. If you were rich enough you could visit a dentist, but that would not necessarily be a better option. A dentist may have better tools and be able to fill cavities, but anesthetics were still 100 years down the road.

When people lost their teeth, they would resort to wearing dentures. These dentures were made of various bones or real teeth from other people and sometimes animals, as experts from the Military Health System report. Contrary to historical myths, President George Washington did not own a single pair of wooden dentures. Washington had used some of his own teeth, as well as different metals and even animal teeth constructed into dental fixtures.

So how did people tend to their pearly whites? According to History, Native Americans would clean their teeth by chewing sticks and herbs or scrubbing charcoal on their teeth. Colonists, on the other hand, did have toothbrushes, as the Charlotte Museum of History reports, and also used them with charcoal.

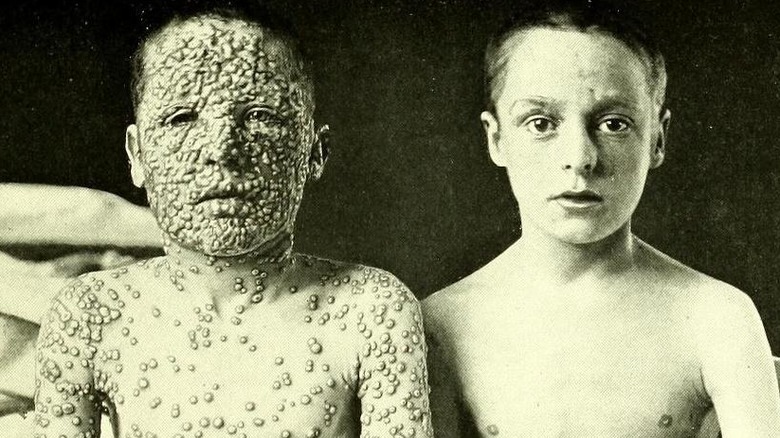

The Colonists' lack of hygiene caused rampant disease

Since colonists rarely bathed and had no knowledge of how diseases were spread, they, unfortunately, succumbed to many epidemics of cholera, dysentery, typhoid, and smallpox. Due to Native Americans lacking natural immunities to European diseases, they succumbed to multiple waves of epidemics from new diseases and were nearly decimated (via New England Historical Society).

According to the Encyclopedia of Consumption and Waste, the common practice in urbanized areas of the colonies was to simply cast garbage into the streets. This would attract animals who would dispose of the rubbish by eating it, while the weather deteriorated the rest. However, this was not a foolproof system as rotting garbage caused vermin carrying diseases to congregate in these piles found in densely populated areas. Leaving garbage festering out in the open also poisoned local water sources and left sludge runoff after the rain.

With lax attitudes about filth, it is no wonder the encampments during the Revolutionary War were often racked with diseases. History reports George Washington sought the aid of Friedrich, Freiherr von Steuben to help improve his camps. One of the thing he insisted on was having proper latrines for the troops.

Women had to join the encampments because the soldiers of the Continental Army could not be bothered to wash their clothes, as "Military History of the American Revolution" reports. These women were responsible for improving the soldiers' health and general appearance (since they also cooked and repaired uniforms).

Soap existed, but it was time-consuming to make and not for the body

The importance of soap cannot be understated — it is a substance that has been in existence since ancient times, as the Conversation reports, long before humanity discovered what germs were. All they knew is that soap, when mixed with water into a frothy lather, made dirt disappear from surfaces. Interestingly over the centuries, people did not primarily use soap for washing their bodies. Colonists rarely used it to clean their skin. Instead, it was used for washing literally everything else they wanted clean.

Acquiring soap was not always so simple as popping into the nearest department store. Women of the house were responsible for manufacturing it. According to historians at Pennsbury Manor, soap-making, despite having simple ingredients, was a time-consuming process.

First, one had to make tallow or suet by melting animal fat in slow boiling water. This mixture was then strained and then cooled. Lye was created by straining boiling hot water through several layers of straw and ashes in a device called a leeching barrel.

Finally, the tallow is melted again, and the lye is slowly stirred in until mixed completely. It was poured into a mold of some sort and left to harden — a process that could take hours or even a few days depending on the quantity and conditions it was stored in. Sounds easy, right?

Colonists had a simple no-fuss cleaning process

It's been established that colonists had bathtubs but barely used them. They had soap, but it was for washing clothes or dishes, and scores of people were convinced washing was actually unhealthy (via Graeme Park). It begs the question, what did they actually do to clean themselves?

The only areas of the body that were cleaned with any frequency were the hands and face, as JYF Museums reports. This was achieved by pouring water from a simple pitcher into a small basin kept in the home. They would splash it on their faces a few times and rub the water between their hands.

Historians a Graeme Park revealed that rather than sit in a tub or wash in a body of water (or swim), colonists would just use a damp cloth and a small water basin to mop their bodies, merely sponging away sweat and filth. Bathing during the colonial period also meant families used one washtub, with the men of the household freshening up first. Women and small children followed, meaning they had the honor of using the rancid, dirty water leftover from the men.

People could go decades without washing, as was the case for one Quaker woman named Elizabeth Drinker. According to historians at Pennsbury Manor, Drinker's husband had built her a shower, effectively putting an end to her 28-year streak of modest bathing practices.

You had to use a communal toilet

Flushing toilets did exist, but they would not become popular until the 19th century, as per Smithsonian Magazine, so people would dispose of their waste (human or otherwise) in latrines called privies. According to "Health and Wellness in Colonial America," by Rebecca Jo Tannenbaum, they were often communal in larger areas like towns and cities but were for individual households in rural areas.

Privies consisted of a small structure built over a hole in the ground with some sort of seating and could be small or facilitate multiple people at once. The privies found at the Webb-Deane-Stevens Museum had some extra features built into them: They had armrests for candles, different-sized seats to accommodate children, and decorative elements added to the building (via the New England Historical Society). If you were wondering about toilet paper: It was nonexistent. To clean up afterward, people would use a plant called lamb's, ear as explained by reenactors at the Charlotte Museum of History.

If privies sound horrible, it is because they were and could potentially cause lethal problems. According to "Health and Wellness in Colonial America," an improperly positioned privy could seep into a family's well and cause numerous gastrointestinal ailments.

Archeologists in Philadelphia discovered a vast cache of artifacts buried in privies near Independence Hall in 2016 (via Live Science). As repulsive as it sounds, human waste matter preserved items like broken cups and bowls, as well as a typeface used at an early printing press.

Wigs were a fashionable home for head lice

We often associate America's colonial fashion sense with powdered wigs. They originally came into fashion about a century earlier to cover up the effects of syphilis, as Mental Floss reports, but during the 1700s, they were a display of wealth and power.

According to Revolutionary War Journal, military officers of the colonial period wore wigs made of human hair, horse, goat, or yak that were simpler versions of the voluminous ones seen in the aristocracy. The most popular men's style in the 1700s features short hair rolled into curls on the sides and swept into long ponytails (sometimes braided) and secured with a ribbon. These wigs were often powdered in various colors; however, by the end of the 1700s use of powder was declining (via "Clothing and Fashion: American Fashion from Head to Toe").

Wigs, unfortunately, attracted head lice, which is sadly ironic since that was part of the appeal of wearing them. Due to how little everyone was bathing themselves, lice liked to burrow into long hair so people would shave off their natural hair in favor of a wig, as "The Colonial Wigmaker," by Laura L. Sullivan, reports.

Who wants to sit for hours having lice picked from their scalp? It was far more convenient to send a wig off to be boiled and cleansed. However, even after a solid delousing, wigs would still summon other bothersome pests like insects who were attracted to the animal fat in styling products.

Shaving and grooming practices

In the early years of the colonies, men did not shave and kept their beards long, according to the "Encylopedia of Hair," by Victoria Sherrow. After the colonies were established and eventually became America, men of status began doing more for their personal care, including shaving. Similar to today, men used a wide variety of grooming products to improve the ease of cultivating facial hair with straight razors (via the Gaurdian). By the mid 1700s, most men were devoid of facial hair.

Colonial women had their own hair removal methods. Author Sarah Read writes in "Maids, Wives, Widows: Exploring Early Modern Women's Lives 1540 – 1714" about how women would prepare depilatory creams. The product was comprised of soap, limestone, and a toxic ingredient: arsenic. They also favored plucked hairlines, which were achieved through meticulous tweezing with pincers.

Even though washing the hair was an infrequent activity, women had a set of hair care routines. For daily maintenance, women would comb away any dead skin and redistribute natural oils. Upper-class women had the luxury of hiring hairdressers who could coif their hair into the elaborate styles seen in the late 1700s (via Chertsey Museum).

Historians at the Chertsey Museum also report that men's hair transitioned from powdered wigs to simply powdering their hair as the century gave way to the 1800s. This style was generally preferred by older men at that point, owed in part to taxes on powder in the 1790s.