The Real Reason Old Churches Have Stained Glass

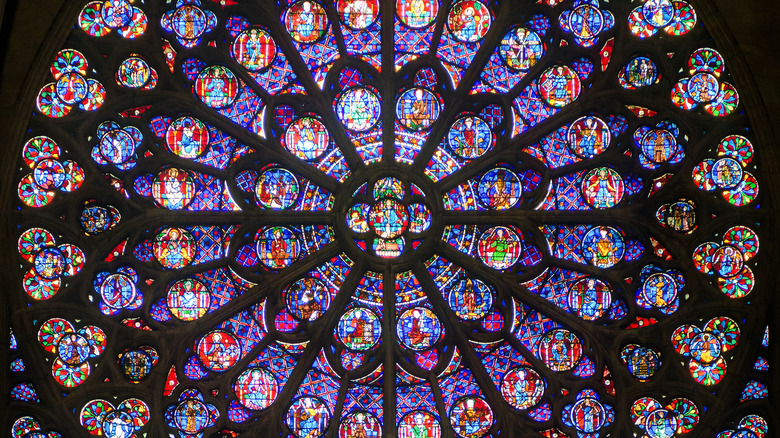

No matter your opinion on Christian doctrine and theology, it's hard to deny the architectural and artistic beauty of old cathedrals. The powerful vertical lines drawing the eye up; the crisscrossed support arches high above; the detailed filigrees along columns and walls. Whether new, art deco cathedrals like Sagrada Familia in Barcelona or old, gothic behemoths like Notre Dame in Paris, cathedrals continue to inspire. But even small, modest chapels and churches often contain a key feature of beauty and storytelling shared with their larger cousins: stained glass.

If you've ever poked around an old church or sat in one during a service, you might have found your head tilted up and your gaze running along with the church's glassy wedges of green, red, yellow, etc. Maybe you saw a nativity, or a scene of Jesus doing the "sacred heart" pose with the first two fingers of the right hand upraised, or St. Peter standing on clouds at the gates of heaven. If so, then you've done exactly what folks hundreds of years ago did and demonstrated the exact purpose of stained glass: to tell stories.

Stained glass served a critical function in medieval European history, as sites like The Stained Leaded Glass Company describe. At a time when common folks couldn't read, stained glass related key Biblical tales like the crucifixion of Jesus or rituals like communion. In a symbolic sense, the light they emitted, and their beauty of form, represented notions of God's love, wisdom, and perfection.

Nature's art turned human art

It's impossible to know precisely when and how ancient peoples deposited just the right ingredients over a fire and saw their sand melt into a gooey, glassy substance. But we do know that by the time we enter Ancient Egypt's Old Kingdom period, we've got archaeological evidence of manmade glass from 2750 and 2625 B.C.E., as The Stained Glass Association of America says. And for the record, yes, glass really is made of melted sand combined with lime and soda ash (sodium carbonate, or natron). All of these materials are naturally abundant on Earth, which is why — given the right temperature and pressure conditions — glass can pop up in places like the Libyan Desert, which has big chunks of yellowish glass just hanging around on its surface, as Stafford Artglass shows.

Barring natural conditions, glass' ingredients need to be heated to about 2,732 degrees Fahrenheit (1,500 degrees Celsius) to form molten glass, as Glass Alliance Europe explains. At that point, the glass can be shaped, molded, contoured, blown, or anything else an artisan envisions. Early Egyptian artisans made their glass, stained or not, into little glass beads. Science News explains how glass-making technology spread through trade routes to places like Mesopotamia and Denmark. As for coloring the glass, folks must have done an awful lot of experimentation. At present, our chemical know-how has advanced tremendously, and we know that iron oxide makes glass green, cobalt makes it blue, etc.

From jewelry to cups to windows

Glassmaking evolved quite a bit from its early Egyptian days until the Catholic Church got on board circa the 7th century. By the 4th century, about 1,400 years before the advent of modern chemistry, folks had already gotten quite handy with coloring glass. The Roman-made Lycurgus Cup, for instance, changes colors depending on the direction of the light that strikes it, as My Modern Met illustrates. Light inside the chalice makes its glass look red, while light outside makes it look green. A rare piece likely forged using silver and gold droplets to give it its color-changing properties, it still baffles modern researchers.

Come the 7th century, glassmakers must have realized that they could use colored glass in windows (bear in mind that most houses didn't have windows until the late 1400s, per the Khan Academy). Simple, geometric, colored glass designs started showing up on buildings such as St. Paul's Monastery in Jarrow, England, which was a direct commission from abbot Benedict Biscop, as the Stained Leaded Glass Company says. Such ventures, which are among the earliest examples of stained-glass windows, featured windows with colored panes overlaid with the metalworking of the window frame itself.

As Daily Art Magazine describes, the first large-scale stained glass used in a cathedral dates back to Augsburg Cathedral in Germany in C.E. 1065. This cathedral also marks the appearance of not just colored geometric shapes in windows but also humanoid figures from Judeo-Christian lore like Moses, Daniel, and David.

Storytelling through artwork

The rise of stained glass windows in churches paralleled the transition from what we call "Late Antiquity" into the early "Middle Ages" (2nd to 6th centuries). As Wondrium Daily summarizes, the Roman Empire had fallen, Europe had dissembled into a bunch of little kingdoms, and the Catholic Church rose as the dominant, unifying force across the continent. Literacy was rare except among clergy, who learned Latin and led liturgies at masses and such. Even Charlemagne, the Frankish king and "Father of Europe" who unified parts of modern-day France, Switzerland, Belgium, the Netherlands, Germany, Austria, and Spain, was illiterate and couldn't even write his own name, as Lumen describes.

What better way, then, to drive home Biblical stories — as well as convey a sense of wonder, beauty, and awe — except through pictorial depictions on church walls? After all, peasants were going to be standing there, anyway. Plus, stained glass served as a reminder of the immense power and wealth of the church. Through the 15th-century, stained glass artistry grew more complex and beautiful, as The Stained Leaded Glass Company describes. From the 15th to 18th centuries, however, styles changed from bold, vivid, and imaginative into something closer to a flattened mural that faded into the background.

This downturn in stained glass artistry and relevance went hand-in-hand with increased literacy and the rise of the printing press (via Wondrium Daily), as well as the Protestant Reformation and a different take on church design.

Beautified mosques and palaces

Stained glass was never limited only to Christian structures. Even by the 8th century, the Islamic world had fully embraced the beauty of colored glass (but not formed into any depictions of the prophet Muhammad, of course). My Modern Met describes the work of Persian chemist Jābir ibn Ḥayyān, whose book "Kitab al-Durra al-Maknuna" ("The Book of the Hidden Pearl") acts as a kind of cookbook for various glass colors, glassmaking methods, and even the creation of artificial gemstones. Straddling the line between ancient alchemy and modern chemistry, ibn Ḥayyān was a consummate researcher who said, "Scientists delight not in abundance of material; they rejoice only in the excellence of their experimental methods."

Over time, much like with European Christian churches, Islamic mosques and palaces incorporated stained glass of increasing complexity and artistry. Countries like Iraq, Iran, Syria, and glassblowing's home, Egypt, grew as centers of the glassmaking industry. As sites like Contemporary Nomad show, stained glass in the Islamic tradition favors bright, sharp colors and lots of flower-like patterns and organic-looking geometry. It's widely believed that this approach to glassmaking is a direct reflection of Jābir ibn Ḥayyān's approach to the craft.

To give the reader an idea of how such traditions carry on even to the present, look no further than sites like Turkish Lamp Wholesaler, based in Istanbul. Commercial venture though they are, the attention to detail resonates now the same as it did hundreds of years ago.

Old traditions and modern art pieces

At present, stained glass has taken on a dual societal role. On one hand, it's an archive of the past and a representation of various world faiths. Older stained glass churches like the aforementioned 11th-century Augsburg Cathedral have not only stood the test of time but have also survived nearby bombings during World War II, as Daily Art Magazine describes. Meanwhile, newer cathedrals like Sagrada Familia employ both mind-blowing architecture and equally impressive interiors full of the light of brilliant and multi-hued stained glass.

On the other hand, stained glass has evolved from its pragmatic-meets-artistic medieval storytelling role into something purely artistic. Installations like Kolonihavehus occupied Brooklyn Bridge Park in 2014, for instance. It used "locally-sourced" plexiglass from the Copenhagen area — as stated on the website of Tom Fruin website, the piece's creator — and has literally traveled around the world on exhibitions. Stained glass artist Neile Cooper, on the other hand, built a full-on, livable cabin in Mohawk, New Jersey, composed almost entirely of stained glasswork depicting scenes from nature like flowers, mushrooms, and butterflies (via Colossal).

And yet, the craftsmanship on display in older cathedrals remains among the most potent in the world, such as Chartres Cathedral (mid-12th century), Sainte-Chapelle (mid-13th century), and York Minster (15th century) (per Daily Art Magazine and the BBC). It's possible to see how art and architecture alone might have turned medieval people of lower status into true believers.