Dark Secrets Of The 1968 Chicago Riot Revealed

The 1960s remain one of the most turbulent and divisive decades in United States history. There was the bravery of those within the Civil Rights Movement and the violence by those who resisted change. There was division over the Vietnam War while fears of apocalyptic destruction by nuclear warfare constantly lingered on one's mind. There were countless protests and numerous assassinations as well as significant cultural shifts within society that invigorated many while leaving others perplexed and concerned for the direction of the country's future (per History). There was also, of course, significant disorder in many cities, places where people had lost faith in those who governed them and civil unrest transformed into outright violence and riots.

During this decade, Chicago became the epicenter for these public outbursts of rage and despair, fueled by the murder of civil rights leader Martin Luther King, Jr., on April 4, 1968, in what became known as the "Holy Week Uprising" (per Smithsonian Magazine). In many ways, the Chicago riots, led by people rebelling against a system that they perceived as continuously failing them, were a reckoning for the city leaders who had either outright ignored or hadn't made good on promises to help fix the problems within the increasingly segregated and unequal city.

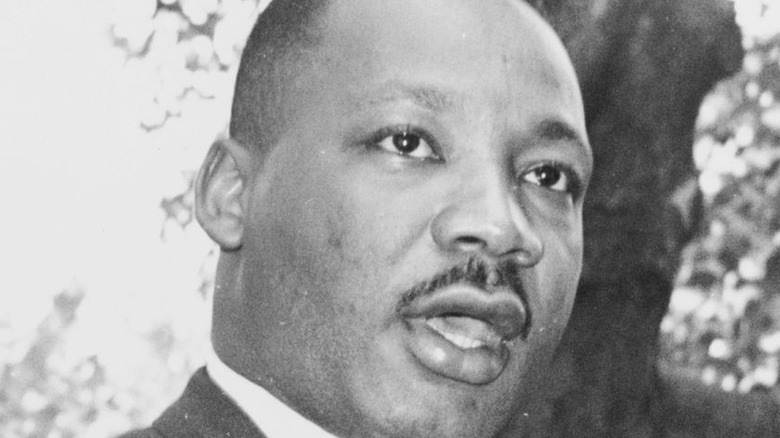

The assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr., sparked the riots

On April 3, 1968, Martin Luther King, Jr., was in Memphis, Tennessee, to support striking sanitation workers. He gave a speech that day in which he said he'd "been to the mountaintop" and "seen the Promised Land." He then noted that he might not make it to the Promised Land with them, but they would make it eventually (via Stanford University). Eerily, his prediction came true. The following day, King was shot and killed while on the balcony of the motel where he was staying, a day before a scheduled march in Memphis.

His death sent shock waves throughout the United States. Protests and riots broke out immediately. According to History, there were protests or riots of some sort in over 100 cities throughout the nation — despite King's own philosophy of nonviolent civil disobedience and President Lyndon B. Johnson calling for a rejection of "blind violence." Some of the most significant of these incidents took place in Chicago, which Smithsonian Magazine states was a city that had a "special relationship" with King.

While King may not have personally or philosophically supported the ensuing riots, he previously had expressed an understanding of them. Two years earlier, he told 60 Minutes, "[A] riot is a language of the unheard." While he also argued that such riots and violence were self-defeating, he ultimately shifted blame towards governments and politicians who continually made promises, yet ignored the problems within Black communities.

Martin Luther King had brought his activism to Chicago in the past

Martin Luther King, Jr., and Chicago had a history. In 1965, the same year of the Selma voting rights campaign, Chicago activists invited King and his Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) to help bring attention to the city's housing, education, and employment discrimination and, in particular, policies that led to segregated ghettos and improperly funded schools (per PBS). King and his family moved into an apartment in a West Side ghetto, bringing significant media attention to the living conditions there. As described by Time Magazine, he gave a speech to over 30,000 people in 98-degree heat in which he declared that Black Americans were tired of being physically lynched in the South and "spiritually and economically" lynched in the North.

In 1966, King helped lead marches into all-white Chicago neighborhoods, which the Associate Press described as being "vigorously resisted" by residents. The King Institute explains how white residents threw bottles, bricks, and rocks at them, shockingly even hitting King in the head and bringing him to his knees. "I have seen many demonstrations in the South, but I have never seen anything so hostile and so hateful as I've seen here today," King said at the time (via PBS). Needless to say, tensions were very high and race relations were very strained in Chicago in the years leading up to King's death. In 1967, King had even referred to Chicago as a "powder keg," according to The Washington Examiner.

Chicago had a long history of racial tension

As demonstrated by the activism of the 1960s and the riots that would engulf the city following Martin Luther King, Jr.'s death, Chicago had significant problems when it came to racial equality. These problems were not new either. In 1919, for instance, Chicago was the location of the worst of the 25 race riots that took place during what became known as the "Red Summer" (per Britannica). The Chicago History Museum describes how, on one hot July day, a Black teenager named Eugene Williams was struck by a rock and drowned in Lake Michigan after accidentally crossing over the unofficial dividing line between the white and Black beaches. As stated in Britannica, violence erupted over the next two weeks and 38 were killed, over 500 injured, and over 1,000 without homes.

That wasn't the only cause of racial strife in Chicago though. As reported by WTTW News, Chicago became one of the most segregated cities in the United States not coincidentally, but by design: utilizing property deeds with racist stipulations, so-called "racial covenants," and deliberate redlining practices. As decades passed, Black community members were simply losing faith that anything would ever change in Chicago (per Chicago Tribune). In the years leading up to the 1968 riots, it also didn't help that the white-owned media viewed activists such as King as a problem. Only days before his death, one Chicago newspaper called King the "most notorious liar in the country" (per Encyclopedia of Chicago).

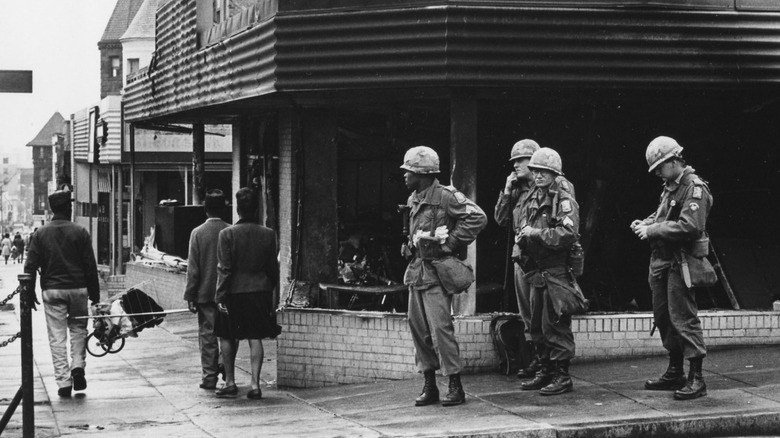

The Chicago riots erupted a day after King's death

While many took to the streets in despair and anger on the evening of the death of Martin Luther King, Jr., the worst of the riots in Chicago erupted the following day. The powder keg, as King had described it before his death, had been ignited, and Chicago exploded into days of destruction and violence. As described by the Chicago Tribune, while the vast majority of residents stayed within their homes or escaped to safety, thousands released their anger onto neighborhoods and communities within Chicago, particularly on the west and south sides of the city. People smashed windows while some looted stores. Others arrived and began setting fire to the buildings, somewhat seeming to target white-owned businesses, but Black-owned businesses and apartments were burned and destroyed as well.

The Chicago Reader recounts how stores, bars, and restaurants all closed down early and downtown Chicago appeared to be a ghost town before night fell. Within the span of a day, nearly 600 fire alarms were sounded. Black leadership made pleas for calm and nonviolent protest, but the chaos was already out of control (per Encyclopedia of Chicago). Reflecting on that fateful evening, a current pastor in Chicago who participated in the burning of buildings that evening as a teenager described their mindset and the anger that they had over King's death, comparing it to having heard one's own parents were murdered (via Chicago Tribune).

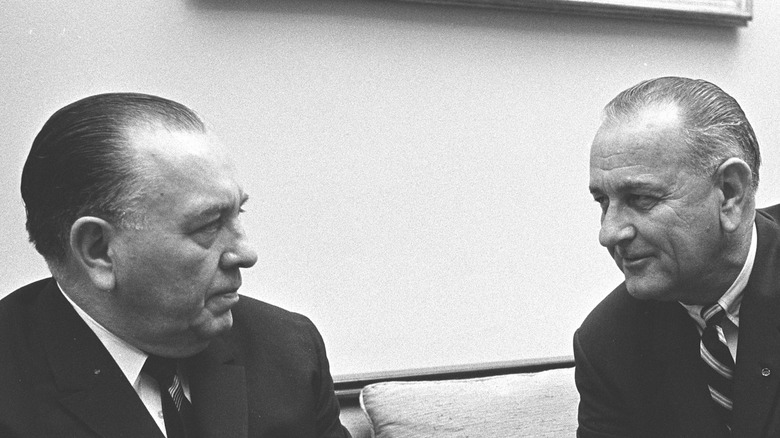

Thousands of police and soldiers descended upon Chicago

As the riots raged, and firemen tried to keep the fires from spreading even further, thousands of police and soldiers were sent into Chicago to try to regain control of the city. On April 6, Chicago mayor Richard Daley phoned President Lyndon B. Johnson stating that Chicago was in deep trouble and needed federal assistance (via Chicago Magazine). President Johnson ordered 5,000 soldiers to be flown to Chicago after also being requested by Illinois lieutenant governor Samuel H. Shapiro, who described the event to the president as an "insurrection," according to The New York Times.

Along with this, there were approximately 6,000 National Guardsmen deployed, thousands of police officers splitting 12-hour shifts, and 2,000 firefighters in action (via Chicago Tribune). Soon, a curfew was also implemented. Tear gas was used to disperse crowds. In the areas where rioting was taking place, there was an outright ban on all sales of alcohol, guns, and ammunition to try and curb violence and help police regain control where law and order had broken down (per PBS). One National Guardsman described how he never even got out of his truck, but they just drove around neighborhoods in order to try and deter people from rioting. Meanwhile, where the police failed to maintain law and order, some south-side ghettos were kept relatively peaceful with the assistance of gangs such as The Blackstone Rangers, who helped keep the peace in their neighborhoods (via Chicago Tribune).

The mayor told police they could shoot to kill

Chicago Mayor Richard J. Daley was no stranger to controversy. According to Britannica, he was considered a "big-city" boss who used the patronage system to maintain power in Chicago politics for nearly two decades. His administration also faced significant blame for the racial segregation within the city's housing. When the riots erupted in 1968, he was infuriated and told the superintendent of police that they had his blessing to "shoot to kill any arsonist" and "shoot to maim or cripple anyone looting" as they attempted to stop the riots (per Time Magazine).

His comments, which he stated publicly, started a firestorm of controversy, not only among civil rights activists but also among otherwise supportive moderates. Reverend Jesse Jackson, a close friend of King's, called Mayor Daley's comments "a fascist's response." Fortunately, according to The Chicago Tribune, police leadership told officers not to follow the mayor's directive. A reporter for The Washington Post noted that it was this police restraint that had saved lives throughout the country's numerous riots. Despite this, Mayor Daley did receive many letters of support, according to Time Magazine, although others pushed back saying you couldn't simply turn every police officer into a "Lone Ranger." In November 2020, Mayor Daley's own great-grandson wrote an op-ed in the South Side Weekly, referring to his great-grandfather as a "horribly racist mayor" and acknowledged that his policies had led to so many of the problems relating to race still plaguing Chicago today.

The destruction was widespread

The rioting in Chicago lasted for over two days. According to the Encyclopedia of Chicago, there were 11 deaths, 48 people injured by police gunfire, 90 police injured, and over 2,100 people arrested. As many as 500 were injured total (per PBS). Over 250 businesses burned to the ground and there was as much as $10 million in damages (per Chicago Tribune). Whole city blocks were leveled by fire. Furthermore, hundreds of Chicagoans no longer had homes to go back to, Chicago Magazine describes. Soon, the bulldozers came in and cleared away the damage. The Chicago Tribune explains that some of these areas have still not recovered or been redeveloped today.

Some historians have referred to what happened in Chicago and across the nation in those days after Martin Luther King, Jr.'s death as the "Holy Week Uprising" (per Cambridge University Press). There were cities that fared even worse than Chicago. According to Smithsonian Magazine, Washington, D.C., was in chaos for nearly two weeks and had $24 million in damages, while Baltimore and Kansas City similarly erupted into chaos.

Black leaders blamed the riots on the city

In the aftermath of the Chicago riots, Mayor Richard Daley claimed his "shoot to kill" and "shoot to maim" remarks had been misunderstood (per PBS). According to Time Magazine, he even called the claim that he said that a complete fabrication, even though he had made the comments publicly. Jet Magazine, a Black-owned print publication founded in 1951 and headquartered in Chicago, didn't believe his retraction. In a scathing story, they argued that Black Americans had been saying for decades that police brutality had been a major problem in Chicago and that white residents believed them to be "lying and exaggerating" about the extent of it.

In another issue of Jet Magazine, they wrote about a commission of Black leaders in Chicago who placed blame for the riots on a city government that "perpetuates white racism," pointing out the irony of how Mayor Daley's commission investigating the riots included only three Black members among its panel of 11. Moving forward, the op-ed argued, Chicago political leaders needed to commit to certain changes in order to prevent future riots: Discrimination needed taken out of employment and housing, more Black workers needed opportunities in union jobs to sustain their families, city schools needed reformed and made more equitable with an inclusion of Black history in the curriculum, and Chicago needed to form an advisory board to properly investigate any and all claims of police brutality.

There were fears this would inspire more riots in Chicago

One of the consequences of the April uprising was that it put the governor, mayor, and city police on edge. As Time Magazine reported at the time, there was also a "psychological impact" of Mayor Richard Daley's "shoot to kill" comments. Some seemed to view it as a warning for future protesters, while others viewed the comments as merely a deterrent. A member of President Lyndon B. Johnson's riot commission noted that there should be no policy to "deprive a person of his life ... for a crime that may involve property worth only a few dollars." As one can imagine, tensions were still incredibly high.

That August, the Democratic National Convention was held in Chicago. April's riots had the city administration nervous, this time exacerbated by the growing anti-Vietnam War movement. When anti-war protesters did show up to the convention, Mayor Daley ordered 12,000 police officers and another 15,000 at the state and federal level to patrol the city, which, according to History, led to an spiraling situation that became known as the "Battle of Michigan Avenue." Chicago Reader explains how the April riots directly influenced what happened during the convention: the brutality of the police during these clashes and the eagerness to crush dissent by Mayor Daley. Smithsonian Magazine expresses the impact of this moment in Chicago's history, a time in which America was divided by the war, people were reeling from the assassinations of King and Bobby Kennedy, President Johnson had shockingly decided not to run for another term, and seemingly riot after riot after riot.

Many Black residents were skeptical of any meaningful change

After a tumultuous decade, many Black residents of Chicago were skeptical of any meaningful change actually happening. A month after Martin Luther King, Jr.'s death, the Associated Press reported on Chicago's segregated housing and quoted residents who previously believed that King's Chicago demonstrations in previous years would lead to change. They were now clearly skeptical. This included King's friend and SCLC member Reverend Jesse Jackson. One city resident called the agreement to desegregate housing "a lie" and "a myth," while another stated that even federal housing laws were not going to change anything in Chicago.

The Chicago Tribune explains that as the Black population continued to grow, housing conditions continued to decline and with the death of so many civil rights leaders — not only King, but also Malcolm X, Medgar Evers, Fred Hampton, and more — many felt hopeless and believed that the movement now lacked the leadership needed to unite different factions within in it to successfully enact any major changes. As the Chicago Reader points out, this also became to time period of "white flight," and as more white residents left the urban center for suburbia, the city seemed to be heading towards becoming more segregated rather than less. According to PBS, Chicago still remains one of the most segregated city's in the country today.