The Untold Truth Of St. Paul's Cathedral

London is full of incredible buildings that aren't just constructions of brick and stone — they're works of art. Few are as recognizable as St. Paul's Cathedral, with its iconic dome that can be seen from across the city.

A lot of historic events have taken place there, from the wedding of Prince Charles and Diana to the funeral of Winston Churchill. It's no wonder that — according to the World Monuments Fund — the cathedral is one of London's most popular tourist destinations, and it's been that way for a long time.

The site that the present cathedral stands on has been dedicated to St. Paul the Apostle since A.D. 604, and while the site's churches have been destroyed again and again, it's a great illustration of just how a city's ever-changing landscape can be shaped by tragedy. For centuries, it was the tallest building in London, and it's still one of the largest cathedral domes in the world.

Still, as popular as St. Paul's is, there's a lot of hidden history in this building. From executions to non-Christian burials, let's talk about some of the rarely repeated stories of St. Paul's.

Elizabeth I had a man executed there, and he became a Catholic martyr

Henry VIII and his family have always had an iffy relationship with religion, and in 1570, the Catholic Church fired back — hard. Elizabeth I (Henry's daughter) was excommunicated as a heretic on orders from Pope Pius V, who then tried to rouse Britain's Catholics in what he undoubtedly envisioned as a grand move to overthrow the British monarchy (via the BBC).

It didn't really work out that way. On May 25, 1570, a man named John Felton nailed a copy of the papal bull excommunicating Elizabeth to the door of the residence of London's bishop. Was he immediately arrested, put on trial for treason, and executed? Absolutely.

Via The University of Sheffield, a pamphlet published after Felton's August execution clarified his crime like this: He "declared that the queen ... ought not to be the queen of England." According to the "Dictionary of National Biography," he was first tortured at the Tower of London before being taken to St. Paul's Cathedral. There he was hanged, cut down alive, quartered, beheaded, and taken to Newgate to be boiled.

The University of Melbourne reported that his execution ballad said: "Because that he hath shed his blood, His quarters stand not all together. ... On London gates they have a place, His head upon a pole, Stands wavering in the whirling wind." He was beatified in 1886.

It was ground zero for reform of the nation's choral program

St. Paul's Cathedral is filled with memorials to some of London's most important people, and one of those memorials — located in the cathedral's crypt — is to a woman named Maria Hackett.

According to St. Paul's, Hackett enrolled her cousin in the cathedral's choristers program in 1810. Little 7-year-old Henry Wintle was an orphan, and Hackett figured a life in the care of the church was better than life on the streets of an unforgiving city. She and Henry quickly found out that wasn't the case.

St. Paul's was, in theory, responsible for the care, upbringing, and education of some of their choristers — the boys who sang in the cathedral's choir. But according to Church Times, the state of the program was pretty dismal. Boys were taught two hours of music a week, and that was the extent of their education and supervision. They were otherwise either out on the streets or hired out to perform at concerts.

Funds were often available to do much more for the children, but in many places — including St. Paul's — the bequests allotted for the choir ended up in the pockets of the higher-ups. Hackett was having none of that, and she kicked off a massive campaign to hold St. Paul's (and other British cathedrals) accountable for the children in their care. Endowments and conditions were made public, and Hackett herself regularly visited the choirs to make sure everything was legit.

The cathedral's collections include a controversial Bible

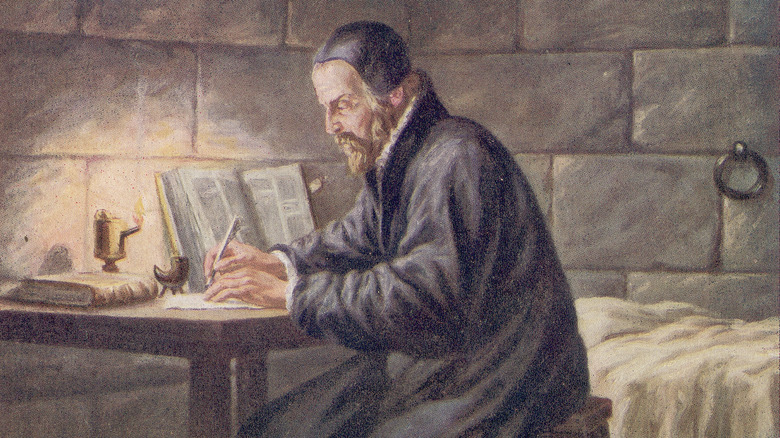

Established authorities can find books dangerous for all sorts of reasons. According to The British Library, William Tyndale published a book in 1526 that was deemed so dangerous that he was hunted down, arrested, convicted of heresy, executed by strangulation, and then burned at the stake. The book? The Bible.

St. Paul's explains that Tyndale was the first to publish an English translation of the New Testament. It wasn't easy to get it printed. His first attempt in Cologne was thwarted in 1525, and it wasn't until he went to Worms the following year that he had 3,000 copies printed. Today, only three copies survive — and one is housed at St. Paul's Cathedral.

They got their copy in 1783, and it's actually pretty ironic. According to "Bible Burning in Reformation England, (download)" St. Paul's was ground zero for the burning of texts deemed heretical. The publishing of Tyndale's translation inspired a book-burning campaign led by the Bishop of London, who preached from St. Paul's Cross and capped things off by torching some books — including copies of Tyndale's Bible. The church claimed that the text had corrupted the original meaning of the scriptures, and it wasn't actually the Bible, but a heretical perversion of it.

By the time St. Paul's got their copy in 1783, it had been deliberately damaged: The pages were shuffled to disguise what it really was.

A Viking grave marker was discovered there in 1852

Breaking ground on any construction project in London has to be like a treasure hunt through history. In 1852, St. Paul's was starting work on a new warehouse when workers dug up a weirdly shaped stone with even weirder symbols. According to Atlas Obscura, they consulted with the British Museum, and it was the museum's expert who recognized the stone as a Viking grave marker. It had been carved in a distinctive style called Ringerike, which had started in Norway and featured various mythological creatures. It's not clear what the creature on the St. Paul's stone is — guesses include a lion-like creature or an animal that's a combination of a few different mythological beasts.

What is known is that it dates back to the 11th century, which was during the rule of a fascinating figure called King Canute. Canute was officially Christian, but he was also the sort of Christian who was totally fine with people having different beliefs. Interestingly, this wasn't long after St. Paul's Cathedral had been sacked. The first church on the site was consecrated in A.D. 604, and they were already on their third building by 962. That one was built after the second was destroyed by the Vikings, and a fourth version was started in 1087, after the third structure was destroyed by a fire.

That one wasn't completed until 1314, though it was consecrated in 1240. A series of tragedies and misfortunes — including fires and severe storm damage — delayed finishing the cathedral. Meanwhile, pagan Vikings might have been buried there alongside their converted kin, possibly accounting for St. Paul's mysterious Viking grave marker.

There's a model of the cathedral... inside the cathedral

In 2020, The Telegraph got exclusive behind-the-scenes access to St. Paul's Cathedral via a tour from head of collections Simon Carter. Among the stops on the tour was a massive attic that contained what looked like chunks of rock. They're the only remains of Old St. Paul's.

The new cathedral was designed and built by Christopher Wren, the architect who helped redesign London after the devastation that occurred during the Great Fire of 1666. Wren had to pitch his ideas to the powers-that-be, and that included convincing them that his vision for St. Paul's was the right one. To do it, he built a 1:25 scale model of his grand plans, and that model still sits in the cathedral today.

Carter also gave a historian from Spitalfields Life a tour of the model, because awesomely, it's possible to go inside. A door in the plinth that it sits on lets two people at a time inside, where they can stand up and look up into the cathedral's massive dome.

There's one more footnote here. The prototype — now aptly called "The Great Model" — cost Wren £600 to build. That doesn't sound like much, but when you adjust it for inflation, Wren's plan seems almost shockingly audacious: He gambled the equivalent of a whopping $190,000 USD on building the model and hoping Charles II liked it.

The cathedral had a dedicated fire patrol during the world wars

One of the most iconic photos of London during World War II features St. Paul's Cathedral, with its dome standing amid the smoke and the ruin of the Blitz. According to Historic England, the cathedral was a high-risk target, and protecting it was considered a priority. That wasn't because the cathedral had any secret military value, but because it and other churches were deemed essential for the morale of the city. St. Paul's survived — even as neighboring buildings burned and collapsed — thanks in large part to the members of St. Paul's Watch.

The Watch was first organized in 1915, when it was German zeppelins flying overhead and dropping bombs on the city. Fast forward to 1939, when German craft were once again overhead and St. Paul's Watch was reinstated.

Volunteers worked around the clock, and the stories are terrifying. On December 29, 1940, somewhere around 28 incendiary bombs were dropped directly on St. Paul's. Volunteers were stretched thin and sometimes had to crawl through wooden rafters to get to bombs that had lodged in the roof. One man — Dean Matthews — found himself face-to-face with a bomb that hit the floor of the library. He later reported: "I have a special affection for the scar left by that bomb on the floor — it represents, I feel, my one positive contribution to the defeat of Hitler!"

They have a team of embroiderers who repair and restore all those vestments

St. Paul's Cathedral might look pretty straightforward from the outside, but on the inside, it's nothing short of labyrinthian. Historic England says that when they were training volunteers for wartime service there, cathedral surveyor Walter Godfrey Allen explained the problem: Even a trained architect would need months to memorize all the rooms, hallways, passages, and staircases.

One of those many, many rooms sits right below 13 tons of bells, and it's the domain of a group of people who are continuing a tradition that started in the Middle Ages — and they're working with cathedral artifacts that are, in some cases, hundreds of years old.

Selvedge says they're the Broderers of St. Paul's Cathedral, and it's their job to repair and restore the huge number of liturgical vestments used by the clergy. They're all volunteers, and they're often professionals trained in places like the Royal School of Needlework at Hampton Court Palace.

Spitalfields Life got a behind-the-scenes look at their workshop and an interview with some of the Broderers, who talked about working with garments worn during events such as Churchill's funeral and Queen Victoria's Jubilee. Materials — some of which are no longer available in the world of modern-day European textiles — often have to be sourced from places like Marrakesh. Best of all? Anyone who has the skills needed can join, and they're often recruiting new members.

Horatio Nelson has a hand-me-down sarcophagus

According to The British Library, Horatio Nelson is one of the nation's most famous tacticians, leaders, and military heroes.

Nelson was killed in the Battle of Trafalgar, and what happened after his death was ... strange. Royal Museums Greenwich says Nelson always knew he had a good chance of dying in battle, so he took a coffin with him when he went to sea. When he was killed by a gunshot in October 1805, he was pickled in brandy and put into the coffin (which was made from the mast of a French ship he'd sunk). By the time his remains got to Gibraltar, Nelson's coffin needed to be put in something a little more sturdy. Before he was laid to rest in the crypt of St. Paul's Cathedral the year after his death, his body would be stored in two more coffins.

And here's the really weird thing: Nelson's final resting place is actually a hand-me-down. The sarcophagus was created by a Florentine sculptor in the early 16th century, and it was meant for the infamously unfortunate Cardinal Wolsey. After Wolsey fell out of favor with Henry VIII and was accused of treason, he died and was buried ... somewhere.

Henry then wanted the sarcophagus for himself, but he died before it was finished, and no one bothered to fulfill the dead king's wish (via RMG). It wasn't until a few hundred years later that King George III gave it to Nelson, and he's still there.

It was targeted by a suffragette bombing

History is a weird thing, and according to The Guardian, one thing that isn't really remembered accurately is the British suffragette movement. Things got real in 1910: That's when police stopped about 300 women from entering Parliament to plead their case on why women should be given the right to vote. Word about the ensuing riot, police brutality, and beatings spread pretty quickly.

It was answered by the Women's Social and Political Union, aka the "suffragettes," who kicked off a campaign of what can only be described as domestic terrorism. Government officials were targeted, and homes were burned and bombed — along with churches, government offices, and public buildings like post offices. Also? St. Paul's Cathedral.

The bomb was discovered on May 7, 1913. St. Paul's Cathedral history says that suffragettes — in sharp contrast to the peaceful protests of activists from the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies, known as "suffragists" — had planned to blow up the Bishop's chair about a year into their campaign of violence, arson, and bombings. The Daily Gazette reported the details, saying, "An enormous bomb, with a clock and battery attachment, was discovered under the bishop's throne at the St. Paul's Cathedral today." The paper went on to say that services had been conducted there the previous evening, but no one had noticed the device. The bomb didn't detonate, and no one was harmed.

It was the site of several executions during the Gunpowder Plot

As far as British holidays go, Guy Fawkes Day is pretty well known. According to Historic Royal Palaces, it's held every November 5 in recognition of the day a group of conspirators tried to blow up Parliament and kill King James I, hoping to end the persecution of Catholics by the Protestant king and his government. Guy Fawkes is obviously the best-known of the plotters. Though he was born into a mostly Protestant family, Fawkes converted to Catholicism when he was young. He was determined to fight for the right to practice his faith.

The plot fell apart when an anonymous letter alerted the government to the plan, and Fawkes was captured in the cellars beneath the House of Lords ... along with 36 barrels of gunpowder.

What happened next, says UK Parliament history, involved a heck of a lot of torture. Fawkes confessed and named some of his accomplices. Eight men were put on trial in January of 1606, and they were quickly convicted. Four were almost immediately taken to St. Paul's Churchyard, where they were executed.

Those four were Sir Everard Digby (who reportedly financed part of the plan), Robert Winter (who was the older brother of another conspirator, Thomas Winter), John Grant, (a brother-in-law to the Winters, who had bought weapons for the group), and Thomas Bates (who was the servant of another conspirator).

They had an official Cathedral Treasure, and he was a man named Maurice

In 2016, Spitalfields Life did a little investigation into what might have been a typo: A man named Maurice Sills was listed in the St. Paul's Cathedral staff directory simply as "Cathedral Treasure." It wasn't a typo, and he was exactly that — a treasure.

Sills made the trip from North London to St. Paul's three times a week, which is seriously impressive for a 101-year-old volunteer. It was nothing new — he'd been volunteering there since 1978. Over the course of decades of service, Sills oversaw all the school visits to the cathedral before moving on to working in the school and library. It's no ordinary library, either: Benefact Trust says it's home to around 13,500 pieces of literature. And Sills? He's the one who cataloged and organized them all.

Sills was also the one answering the letters, taking on research requests, and making sure there were several copies of each and every service performed at the cathedral. A treasure, indeed!

Sadly, Sills passed away in 2017, just a year after giving the interview and a few weeks before he would have turned 102. St. Paul's paid tribute to him on their social media and held funeral services for him.

There's a reason you can see it from so many places in the city

Visitors to London will probably notice that St. Paul's Cathedral can be seen from a lot of different vantage points across the city. That's by design: The City of London has established a number of Protected Views of several of the city's most recognizable features, including the Tower of London and St. Paul's. In a nutshell, it means that no massively tall buildings can ever be built to obstruct the views of those landmarks.

There are eight places across the city that have protected views of St. Paul's Cathedral, says CNN: Blackheath Park, Primrose Hill, Hampstead Heath's Kenwood House and Parliament Hill, Greenwich Park (specifically, the view from the General Wolfe Statue), Alexandra Palace, Westminster Pier, and King Henry VIII's mound.

Whether or not these views will continue to be protected is a hotly debated topic, with some — particularly developers — saying that London needs to rethink things if the city is going to keep growing. Others say the views not only need to stay, but stricter regulations should be on the books. According to Architects Journal, London mayor Sadiq Khan called for expanding the protected views area to include more distant boroughs after construction began on the Manhattan Loft Gardens tower, infringing on the views from Richmond Park's mound.