How Listerine Went From The Operating Table To Dental Hygiene

According to Spear Education, mouthwash dates back several centuries, though not exactly as we know it today. The Ancient Romans were said to have bought Portuguese urine to rinse their mouths. Per Smithsonian Magazine, there was a belief that urine whitened teeth and for this reason, it became incredibly popular. At one point, Emperor Nero taxed urine due to its widespread use (via Contractor & Business Weekly). Beyond this, there have been other versions of mouthwash, including simple cold water, mint and vinegar, and even tortoise blood. However, as Oral B explains, modern mouthwash, the one that is still used today, was invented in the 1800s.

The Sapulpa Times reports that this is all thanks to Dr. Joseph Lawrence. In 1879, he developed Listerine. Made with essential oils that include thymol, menthol, and eucalyptol (per Clinical Aromatherapy), the Kilmer House writes, Listerine was first marketed as a general antiseptic for cuts, insect bites, and more. It was eventually sold as a floor cleaner, deodorant, and remedy for various ailments, including dandruff and gonorrhea (via the National Museum of American History). That being said, Listerine would have never been possible if it weren't for the work of Louis Pasteur and Joseph Lister. Both men paved the way for Lawrence to create Listerine.

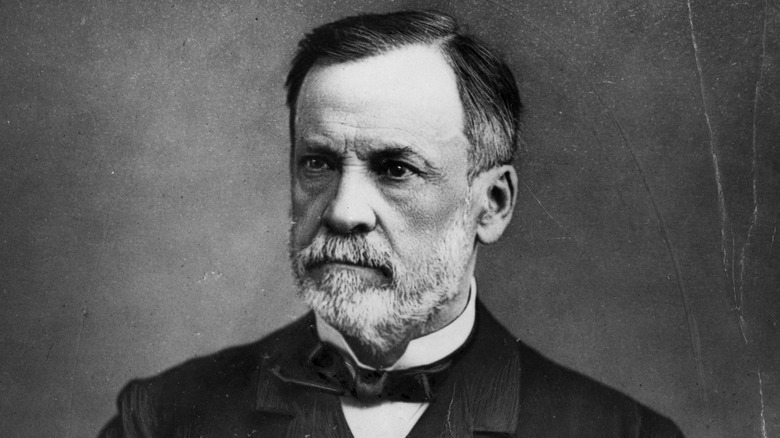

Who was Louis Pasteur?

Born in 1882, Pasteur was a French scientist who is known for developing the germ theory of disease (via the Science History Institute). As a child, Biography writes, he was a less than stellar student. However, he eventually received a bachelor's degree in science, and by 1847, he had a doctorate in the subject (per Britannica). Pasteur became a chemistry professor and first studied the characteristics of tartaric acid, a chemical compound found in fruit and wine.

In 1854, he switched his focus to alcohol fermentation, and in 1857, Pasteur further formulated the germ theory. In simple terms, he realized that bacteria were the cause of certain foods, such as milk and wine, going bad. Ultimately, Lemelson-MIT reports, Pasteur discovered that by heating these substances, he could get rid of the bacteria. This process, per the Science History Institute, is now known as pasteurization.

Pasteur quickly recognized that this breakthrough went beyond the fermentation of food; it also applied to bacteria-causing diseases in both humans and animals. Thus, his germ theory of disease was born (per Lemelson-MIT). Pasteur subsequently developed vaccines for anthrax, rabies, and chicken cholera in livestock. After successfully treating his first human rabies patient, the Pasteur Institute was founded in 1888. To this day, it still produces vaccines. Louis Pasteur died at the age of 72 in 1895 (via Biography).

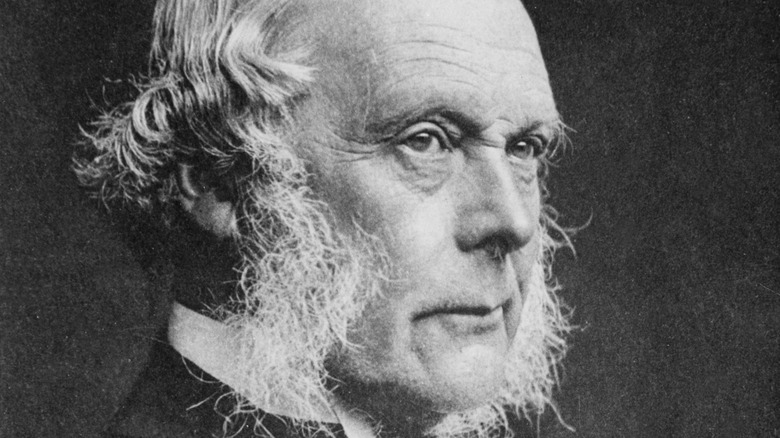

Joseph Lister was inspired by Pasteur

Britannica writes that one of Pasteur's contemporaries was Joseph Lister, a British surgeon. Per Biography, Lister even attended Pasteur's 70th birthday celebration at the Sorbonne in Paris. Now referred to as the "father of modern surgery," Lister was heavily inspired by Pasteur. Taking Pasteur's germ theory of disease, Lister surmised that bacteria was causing gangrene and infections in patients. ThoughtCo. states that in the 1860s, Lister began to make an effort to sanitize wounds as well as his operating room. Prior to this, surgery was crude and unhygienic. Sheets were left unwashed and the same medical instruments were used on different patients, sometimes without being cleaned first.

This undeniably led to a high mortality rate — so much so that surgery was nearly eliminated as an option at hospitals (via ThoughtCo.). According to the Canadian Journal of Surgery (posted at the National Library of Medicine), Lister's peers believed that the smell that arose from wounds was contaminating the air and causing infections in patients. Lister, however, thought otherwise; he believed the wound itself was the problem.

Upon reading Pasteur's germ theory, he decided to implement antiseptic methods. The Sapulpa Times explains that Lister directly applied carbolic acid, which was then used to treat sewage, to wounds. Additionally, he created a device that sprayed carbolic acid into the air before surgery (per the Science Museum Group). The infection rate in patients drastically decreased and Lister forever revolutionized antiseptic measures in surgery. Soon after, he influenced Robert Wood Johnson and Dr. Joseph Lawrence to continue the modernization of surgical practices (via the Kilmer House).

Dr. Joseph Lawrence named his new product after Lister

The Kilmer House explains that Johnson later established the Johnson & Johnson company to create surgical dressings, while Lawrence got to work in making an antiseptic for surgery. In 1879, Lawrence, along with Jordan Wheat Lambert, created Listerine in St. Louis, Missouri (per the National Museum of American History). Lawrence named his creation after Joseph Lister, to honor his medical contributions. As for Lambert, he was a local pharmacist who helped Lawrence acquire the ingredients he needed to make Listerine's alcohol- and essential oil-based formula (via the Sapulpa Times).

In 1881, Lambert licensed Listerine and established the Lambert Pharmacal Company to market the product. The Kilmer House reports that Listerine was one of the first brands to list its ingredients on the bottle for consumers. Although it was first advertised as a catchall antiseptic remedy with multiple uses, that all changed in 1895. Previously, its suggested use was to clean and disinfect small cuts and wounds.

That year, Listerine reports that studies found that the product was a potent oral rinse.The Lambert Pharmacal Company subsequently began to peddle Listerine to dental health professionals as an oral antiseptic. It was sold only to dentists until 1914. That's when the company decided to make an over-the-counter-product. Per the Sapulpa Times, consumers showed little interest in Listerine until a marketing boom in the 1920s caused sales to skyrocket.

Halitosis was a marketing scheme

According to the Kilmer House, Lambert's sons were tasked in finding a solution to low Listerine sales. Per Smithsonian Magazine, that's when they decided to bring back an old Latin word, halitosis, into the 1920s. Simply put, they made halitosis, otherwise known as bad breath, sound like a medical condition that could potentially hinder people's lives. Io9 reports that Listerine's subsequent ads tugged at people's fear and apprehension.

For example, they stated that an unmarried woman had failed to find someone due to this ailment, among other things. Needless to say, it worked, and sales of Listerine dramatically increased (via Listerine). Per the Sapulpa Times, James B. Twitchell, an advertising scholar, later stated that, "Listerine did not make mouthwash as much as it made halitosis." Moreover, it created what advertisers called "the halitosis appeal" and "the halitosis influence" (per Advertising the American Dream).

In other words, anxiety could be used in order to sell a product. This sudden rise in popularity allowed the Lambert Pharmacal Company to push Listerine as a multi-use product. This included as an after-shave, deodorant, and a remedy for sore throats. The company later created a toothpaste and by 1928, their marketing budget had been increased to a whopping $5 million (via Advertising the American Dream). In comparison, their budget was $100,000 in 1922.

Listerine and the COVID-19 controversy

In recent decades, Listerine has developed a variety of mouthwashes, with whitening properties and more. However, the Kilmer House points out that their advertising stopped using fear as a tactic. Currently, the company, which has been owned by Johnson & Johnson since 2006, uses their product to encourage healthy dental habits. In 1977, The Washington Post reported that the Federal Trade Commission ruled that certain claims that Listerine was making were misleading. This specifically was referring to the use of the product as a cold remedy. The FTC stated that the company had to reveal that Listerine "will not help prevent colds or sore throats or lessen their severity."

In 2020, CNN writes, a similar claim was made regarding Listerine and COVID-19. However, this allegation was made not by Listerine but by various social media reports. It asserted that using mouthwash could kill the virus. Dr. Graham Snyder, a professor at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, disputed this claim and explained that "You can't sterilize your mouth."

This later prompted Listerine to release a statement that read that there was little to no scientific evidence that backed the product as a method of prevention or treatment. Even so, Salon writes that in December 2021, Republican Senator Ron Johnson publicly exclaimed that "Standard gargle, mouthwash, has been proven to kill the coronavirus." Although mouthwash has been found to reduce the amount of the virus in a person's mouth (via Reuters), both Listerine and Johnson & Johnson have continued to refute claims of its use as a cure for COVID-19.