What Hygiene In America's Wild West Was Really Like

Somewhere in the 19th century, a cowboy rides into town after a long, hot day on the range. A woman is a soggy, sweaty mess after washing laundry all day. And a child is crusty with dirt after playing outside on a barren prairie. How in the world did any of them get clean? It was a real trick, seeing as Western author Deborah Hufford confirms that wells and water pumps were a rarity in the Old West. Beginning in the 1840s, only large cities like New York, says Berkeley University's James D. Lutz, had indoor plumbing. And it would take nearly a century before even half of America's households had indoor hot water.

Even if people could access clean water in the old days, it took some convincing for everyone to believe that "Cleanliness is, indeed, next to godliness," as preacher John Wesley said back in 1791. Yet author David Dary notes that in the early 1800s, bathing was believed to wash away "protective oils" that were necessary for healthy skin. Not until 1887 did manuals like "The Happy Home Guide" explain that everyone should "bathe the whole surface of the body with good soap and water at least once a week." So how was this accomplished? Read on to find out about hygiene practices in the Wild West.

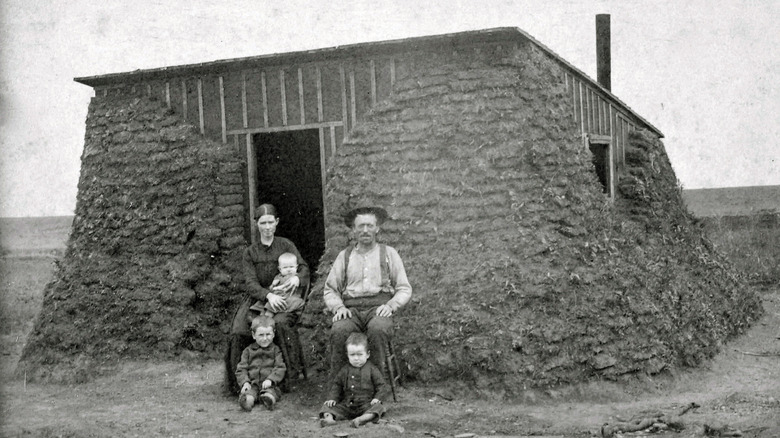

Cleanliness did not begin in the home

Thanks to our air-tight homes and numerous cleaning supplies today, we really don't think much about what it took to clean house in the West. But to those coming from luxurious homes back East, housecleaning was challenging — especially in sod houses on the prairie. Nebraska Studies describes these homes as having dirt floors with "dirt, bugs, snakes, leaky roofs, and poor lighting." Sometimes, says Iowa History, homesteaders poured greasy dishwater on the floor to keep the dust down, which was hardly sanitary. And PBS recounts the memoirs of homesteader Bertha Anderson, who tells of a leak in the roof soaking her children's pajamas and making her rug "a dirty mess."

There were other germy perils, too, such as washing dishes. Springfield-Green County Library in Missouri talks of the lack of sinks. Most pioneers used buckets, hauling in water, warming it to near scalding temperatures, and using harsh, homemade lye soap. Busy public eating houses, however, rarely took time to wash the dishes. In her book "The Gentle Tamers: Women of the Old Wild West," noted history author Dee Brown tells of a lady who stopped for dinner at a Kansas ranch in 1855. She wrote that the men around her fairly gobbled their food, and as they finished their meals their dishes were wiped, not washed, for the next diner.

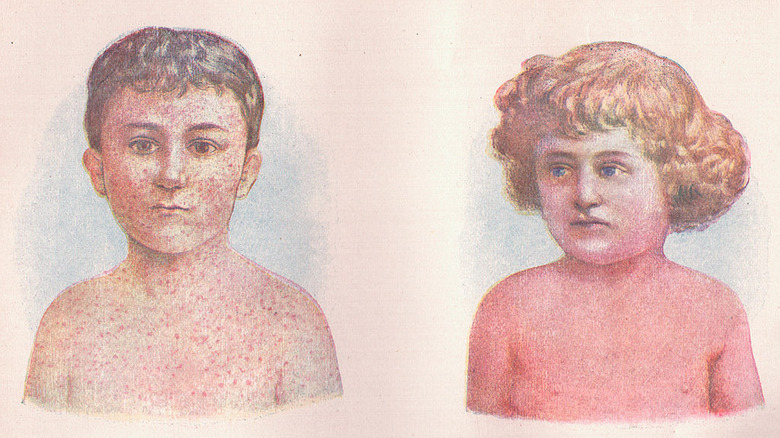

Germs: the misunderstood malady of the West

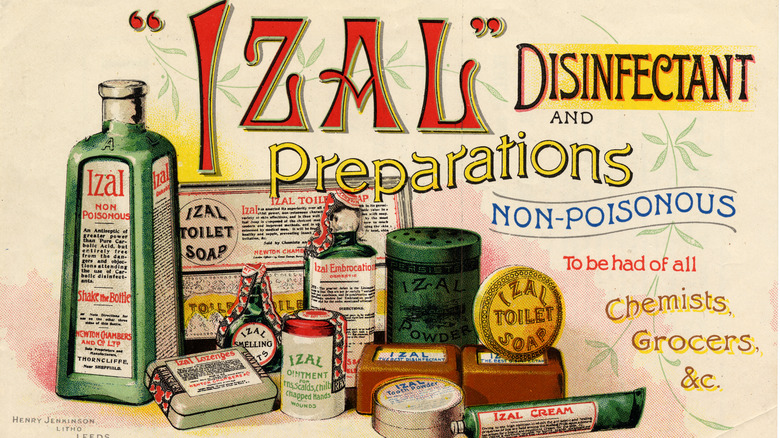

During the 1800s, folks didn't know, or think much, about germs and how they were spread. Arizona historian Marshall Trimble explains in True West Magazine that eating from the same plate, drinking from the same cup, and even sharing the same towel to wipe the beer from one's mustache at the bar were very common. Thankfully, "The Happy Home Health Guide" informed readers that germs could be spread via the fat from sick animals used to make soap or through feather mattresses that were used for years without being cleaned. Germs, the manual warned, could even be spread by people with consumption or scarlet fever. Notably, the guide was published during the development of what Harvard University calls "modern germ theory" between 1870 and 1900.

In 1889, a viable attack against germs finally came along. Gustave Rapuenstrach, according to Bloomberg, was the German scientist credited for inventing Lysol, the ultimate germ-killer that remains highly popular today. The New York Times says that early on, ads for Lysol claimed the stuff was a great "household cleanser" and could even be used for feminine hygiene! Today, however, Lysol warns that the product should only be used on surfaces, and should never be used on skin, animals, or food.

The art of the stink in the Old West

According to NBC News, humans are smellier than anyone else in the animal kingdom. We also tend to attract mosquitos, which can spread deadly illnesses, such as malaria and yellow fever. And, we emit a pungent, unpleasant odor besides. What to do about that wicked smell in the Wild West? Historian Elena Sandidge explains that most folks made do by washing daily from a basin of hot water and hitting the most troublesome spots on the body: "face, armpits, and privates." Naturally, not everyone had the means to take a daily basin bath. Cowboys on the range, for instance, were forced by their circumstances to share a common washbasin with just enough water to clean their faces and hands.

Other folks, especially women, tried masking body odor with perfume, says Tom's of Maine. Thank goodness for Mum deodorant, made from a "waxy cream" and zinc oxide, which came out in 1888. The market was soon saturated with other products as well. One of the earliest advertisements for deodorant was Zedonia, a mysterious solution marketed by the Magic Novelty Company in far-off Maryland in 1893. But the first antiperspirant, says Smithsonian Magazine, was not introduced until 1903. It was called "Everdry."

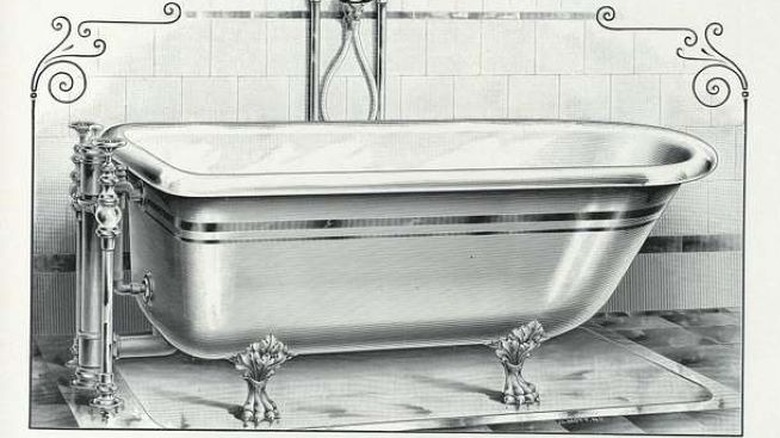

Early bathtubs were too expensive for most households

In 1917, journalist Henry Mencken published an article claiming that the bathtub was invented in 1842 and that the first bathtub in the White House was installed by President Millard Fillmore. Both statements are false, explains the Museum of Hoaxes; Mencken was merely having some fun with his readers. The White House does confirm that President Andrew Jackson had a "bathing room" installed in 1833. Folks in the West, however, would not see such a luxury for some time, according to author Deborah Hufford. As late as the 1870s, homesteaders on the frontier made do with nearby streams and even the horse trough outside. Why?

Simply put, it was a hassle to carry water into the house, heat it up, and fill a tub. Besides, there was no way to really purchase a real tub until Sears, Roebuck & Co. began publishing mail-order catalogs in 1894. In 1895, says Western author Kristin Holt, a Sears catalog tub cost around $22.50, or nearly $800 today. As more homes began purchasing bathtubs, the family shared the same bathwater, one person at a time, to save on labor. The Christian Science Monitor clarifies that the habit of the ritual "Saturday night bath" was because everyone wanted to be clean for church on Sunday.

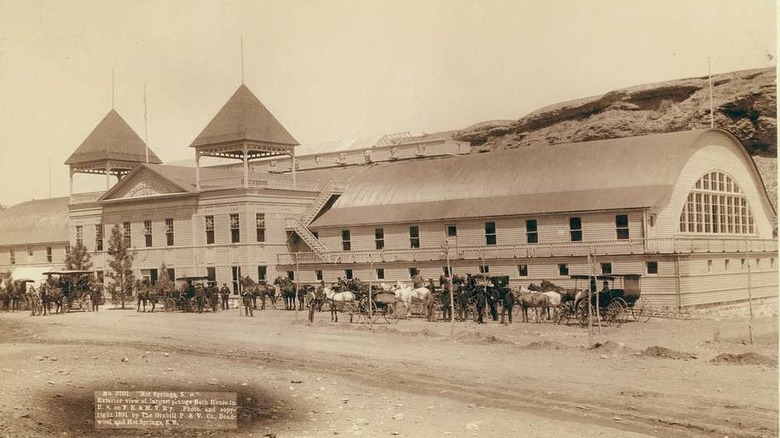

Public bathhouses and private bath services

Travelers during the 1800s eventually found the need for a more regular cleansing bath. By the 1850s, three types of public baths were available. The first was a common bathhouse with private tubs, as recorded in California in 1858 when public bath owners paid $2.00 for water per tub. The water was likely reused; an 1863 article in a Nevada newspaper reported that a bather who fell asleep for five and a half hours was charged $5.50, or a dollar per hour.

In bigger cities, Turkish baths were highly popular. An 1870 guide, "Personal Beauty: How to Cultivate and Preserve It," described a Turkish bath not unlike today's sauna, and recommended it for health and weight loss. More bathing houses would follow. In 1890, James Lick opened a luxurious bath house in San Francisco which remained in business until 1919, says the San Francisco Business Times.

The third type of bath involved the brothels that reigned across the west for decades. "Good Time Girls of the Rocky Mountains" notes that many brothels included private or shared bathrooms. Sometimes, customers could enjoy services while in the tub. At the turn of the century, The Oasis, a parlor house in Idaho, charged between $50 and $80 for a bubble bath.

Doing the duty in the outhouse

In the days before indoor plumbing, says the National Museum of American History, "chamber pots," small porcelain bowls with a lid and a handle, were placed near the bed for use at night. Outside, pioneers constructed outhouses, a simple shack with a pit dug out underneath. Author Deborah Hufford says outhouses have been around America since the 1700s, with one or two holes carved into the seat inside — one for adults, and a smaller one for children. Distinctly Montana magazine explains that the crescent moon or starburst carved in the door provided not only light but also much-needed ventilation.

During the 1800s, according to True West Magazine, "just about" every hotel, house, saloon, and store had a privy in the back. These discreet yet popular places could be so busy that some of them were two stories tall, says Roadside America. One hotel in Montana, writes Legends of America, featured an outhouse with a dozen seats. Like today's modern bathrooms, outhouses offered a level of privacy to read, or perhaps have a smoke or even a nip of liquor, says the Missouri Folklore Society. They could also serve as trash pits, sometimes for weapons or other tools used in a crime.

Indoor plumbing was a boon to families

According to James D. Lutz of Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, indoor plumbing didn't arrive in America until 1842 — but that was in the big city of New York. Eight years later, indoor plumbing was available in homes across the West too but was more expensive than the average homeowner could afford. By 1920, only 1% of homes in the U.S. could afford any kind of indoor plumbing at all. California's Leonis Adobe Museum explains that someone eventually thought to build an elevated outdoor water tank, thereby allowing water to flow downhill into an interior pump. By the 1870s, at least some kitchens featured a hand pump at the sink.

For several more decades, pumped water was the best most households could hope for. By 1884, affluent homeowners could install actual plumbing, according to Professor Barbara Penner. Not so for the rural homes of the Wild West. Beginning in 1895, writes author Kristin Holt, Montgomery Ward was advertising a "folding bathtub" that came with a gasoline heater, but no plumbing. Nebraska's Wessels Living History Farm says that indoor plumbing would eventually come to city dwellings long before those in rural areas could have such a luxury. Those living in the country finally got their wish — towards the end of the 1930s.

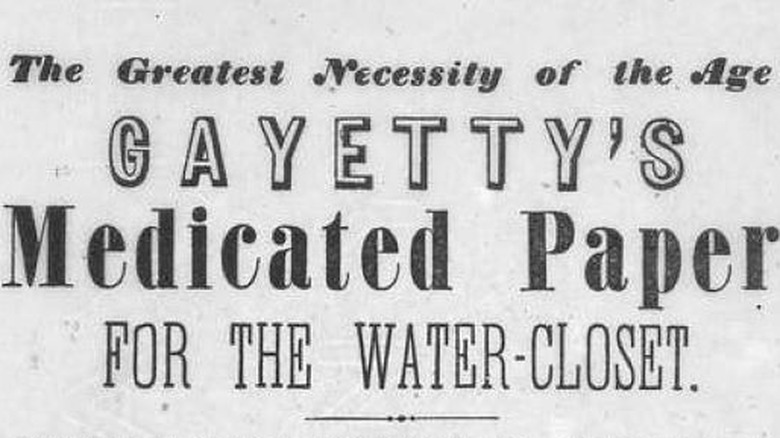

Imagine a world without toilet paper

While Americans embraced the idea of an outdoor bathroom, it seems nobody thought about toilet paper for some time. Prior to that wonderful invention, says the History Channel, folks used corn cobs and pages from magazines and catalogs. Not until 1857 did New Yorker Joseph Gayetty market "medicated paper," and that was only available by the sheet. It would be 1890 before toilet paper came by the roll. A year later, one Seth Wheeler invented the toilet paper holder, which settles an age-old debate: does the paper go over or under? Business Insider has an image of the original patent, which clearly shows that toilet paper goes over the roll.

Less abrasive toilet paper was in use by 1907, according to PBS. Still, not everyone could afford, or access, toilet paper back in the day. Farmer's Almanac acknowledges that readers had been drilling a hole in the annual issue since 1818, in order to hang it from a nail in their favorite potty place to read, but also use as toilet paper. Beginning in 1919, the Almanac included a pre-drilled hole just for that purpose. Even so, according to writer Sue Bowman at Lancaster Farming, paper, plants, rags, and "soft" corn cobs remained highly in use until the 1920s.

Care of the nether regions was particularly precarious

Between 1837 and 1901, downstairs hygiene was a mysterious subject. Women were particularly uncomfortable, since their layers of petticoats prevented them from lifting their clothes to use the bathroom. Rose Heichelbech of Great Life Publishing's Dusty Old Thing confirms that women's pantaloons in the Old West were crotchless, allowing them to simply hover over the toilet. And to combat the odors of their private areas, says the BBC's Laurel Ives, regular douching prevented "misery, woe, and utter despair." For monthly menses, says Femme International, ladies used grass, cotton, rabbit fur, rags, or sheep's wool to keep themselves clean before sanitary pads came about in 1888. Tampons, Rainy Horowitz of Arizona State University writes, wouldn't be invented until 1931.

Men, meanwhile, were sometimes terrorized about their pubic area; by 1894, Dr. Otterbourge of Salt Lake City was just one "doctor" whose frightening advertisement addressed men's troubles, with the promise of a cure. Ultimately, however, doctors decided that the best way to keep men's genitals cleaner and disease-free was via circumcision, according to Kate Ringer at the University of Idaho. Indeed, circumcision was believed to prevent or even cure such maladies as epilepsy, "mental retardation," masturbation, and even syphilis, says The Circumcision Debate. And for good measure, said doctors, it would also somehow cure hysteria in women.

Bad teeth were just a way of life in the West

"Care of teeth is important ... and children should be taught to clean them regularly," warned "The Happy Home Health Guide" in 1887. Tooth powder, and later toothpaste, were indeed available by the mid-1800s, according to Colgate. There were also lots of easy home recipes for cleaning teeth, including one published by the Dodge City Times in 1879. And, Marshall Trimble explains, dentists were aplenty by then. But infections from procedures were common, and could often prove deadly.

The problem with going to the dentist was the pain involved with both a toothache and treatment. While PBS verifies that anesthesia was available in Massachusetts by 1846, the stuff was hard to procure in the far-off West. Once, in 1886, author Kristin Holt says gunfighter/outlaw Clay Allison was so mad at his dentist for extracting the wrong tooth that he straddled the man and pulled out one of the dentist's own molars. Sometimes too, dentures were the only answer. False teeth actually date back to 2500 B.C., says Celeste Abraham of the National Library of Medicine, but they could be expensive. Emily French, who lived in Denver during the 1880s, described herself as a "hard-worked woman" who could barely afford her false teeth.

Barbers and beauticians were part of the Western scene

In the Old West, says author Vicky J. Rose, barbers offered much more than a shave. They were dispensers of advice but also performed dentist and doctor duties if none of those professionals were around. Indeed, a barber was a welcome sight in any town. When barber Henry Edwards announced he was opening a full-service bathhouse in Mokelumne Hill, California, in 1852, the Calaveras Chronicle not only applauded him as "one of the most expert and light-handed professors of the tonsorial art" but also stated that nothing was more "conducive to comfort and health than personal cleanliness."

Women, too, appreciated health and beauty tips. Smithsonian Magazine writes that although most women refrained from using "paint" on their faces lest they be confused for sex workers, that didn't stop them from using lotion, powders, and homemade beauty products. And in 1895, the National Women's Hall of Fame reports, a former domestic servant named Martha Matilda Harper opened the first women's hair salon. Thirty years later, over 500 Harper salons spanned across the globe. Meanwhile, newspapers like the San Francisco Call dispensed beauty advice, including, in 1899, a full page of advice to cure wrinkles by exercising the face.

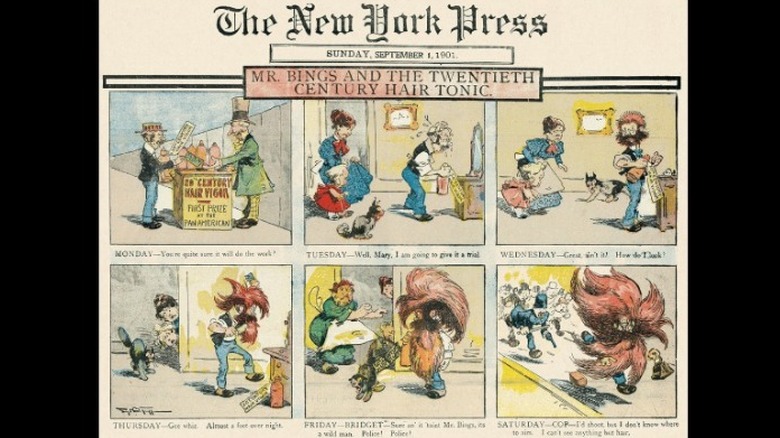

Lice and other hairdo havoc

So, with a shortage of fresh water, indoor plumbing, and bathtubs, how did folks in the Old West wash their hair? Elena Sandidge offers that frequent brushing was employed in between washes. Shampoo hadn't been invented yet, so pioneers turned to eggs, vinegar, and other household products to clean hair and save it from the harsh soaps available. A 1900 article in the San Francisco Call advised using glycerin to make little girls' hair beautiful. Shampoo eventually did come about, in 1898, but only in powder form, writes author Rose Heichelbech. However, it had to be ordered from Germany; not until after the turn of 1900 did American companies like Breck offer liquid shampoo.

In 1887, "The Happy Home Health Care Guide" advised washing the hair any time you bathed. The book also identified several types of lice that could infest the hair and body, and listed treatments that included using water from boiling old potatoes. According to Lice Doctors, early treatments also included a salve of vinegar and lard, or literally picking the lice out of the hair with a lice comb. Scientific American explains that lice can actually kill you. In fact, two men, Howard T. Ricketts and Stanislaus J.M. von Prowazek, contracted typhus while trying to research the little parasites.

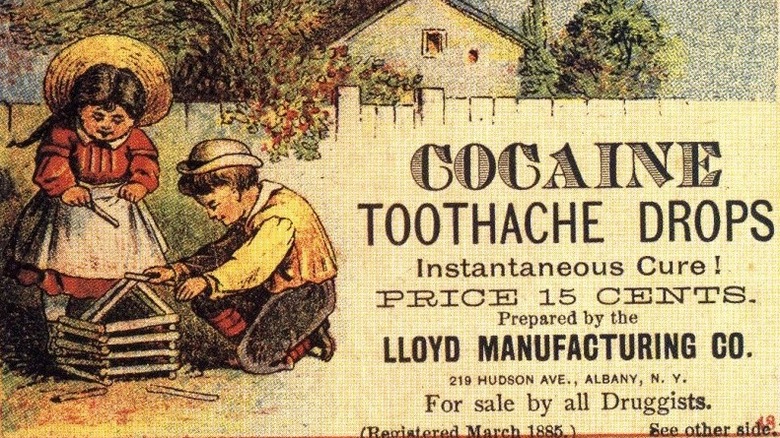

Medicines of the Old West versus hygiene

What an ugly cycle: without water, people in the Old West couldn't bathe. Dirty people got sick. Without proper medicine, they died. Surprisingly, however, some of the medicines used to cure those who lived remain the same today. Take aspirin, for example, which the Aspirin Foundation confirms was known as salicin when professor Johann Andreas Buchner discovered it in 1828. Salicylic acid was officially marketed as Aspirin in 1899. Today, according to WebMD, it relieves pain and swelling, and helps lower blood pressure. Then there is cocaine, which was widely used in toothache drops during the 1880s, says the National Library of Medicine. The drug is still used as a local anesthetic, according to the Mayo Clinic.

One other medication deserves mention: Morphine, which author David T. Courtwright (per Smithsonian Magazine) writes was in use by the 1870s and considered a miracle drug to help the wounded rest easy so they could heal faster. Morphine also provided relief for delirium tremens, gastrointestinal issues, headaches, and menstrual cramps.

The one drug the Old West could have used? Penicillin, which the Science Museum says wasn't discovered until 1928, after Dr. Alexander Fleming of London, left a Petri dish out while he was on vacation.